Yo, what’s good? Shun Ogawa here, dropping in to spill the tea on one of Japan’s most enduring and low-key revolutionary cultural scenes: the Showa-era kissaten. Bet you’ve seen pics of these spots on the ‘gram—moody, wood-paneled interiors, velvet chairs that have seen things, and wisps of steam rising from some wild-looking glass contraption. It’s a whole aesthetic, for real. But let me tell you, it goes way deeper than a retro filter. These places are not just cafes; they are time capsules. They’re living museums of a bygone era, the Showa period (1926-1989), a time of massive change in Japan. But here’s the real kicker, the plot twist for our 21st-century minds: these kissaten are, and always have been, masters of sustainability. Long before “zero-waste” was a trending hashtag, these quiet, unassuming coffee houses were living it. They are the OG zero-waste cafes, the blueprint for a kind of mindful consumption that the modern world is desperately trying to get back to. They didn’t do it to be trendy; they did it because it was just the way things were done. It was about quality, respect for materials, and a deep-seated cultural aversion to waste known as mottainai. So, buckle up. We’re about to take a deep dive into the world of kissaten, exploring how their very existence is a masterclass in sustainability, community, and the fine art of just… slowing down. It’s a vibe that’s more relevant now than ever.

This deep-seated cultural aversion to waste, known as mottainai, is the same philosophy that inspires the art of using a single cloth for everything from bags to stylish wraps.

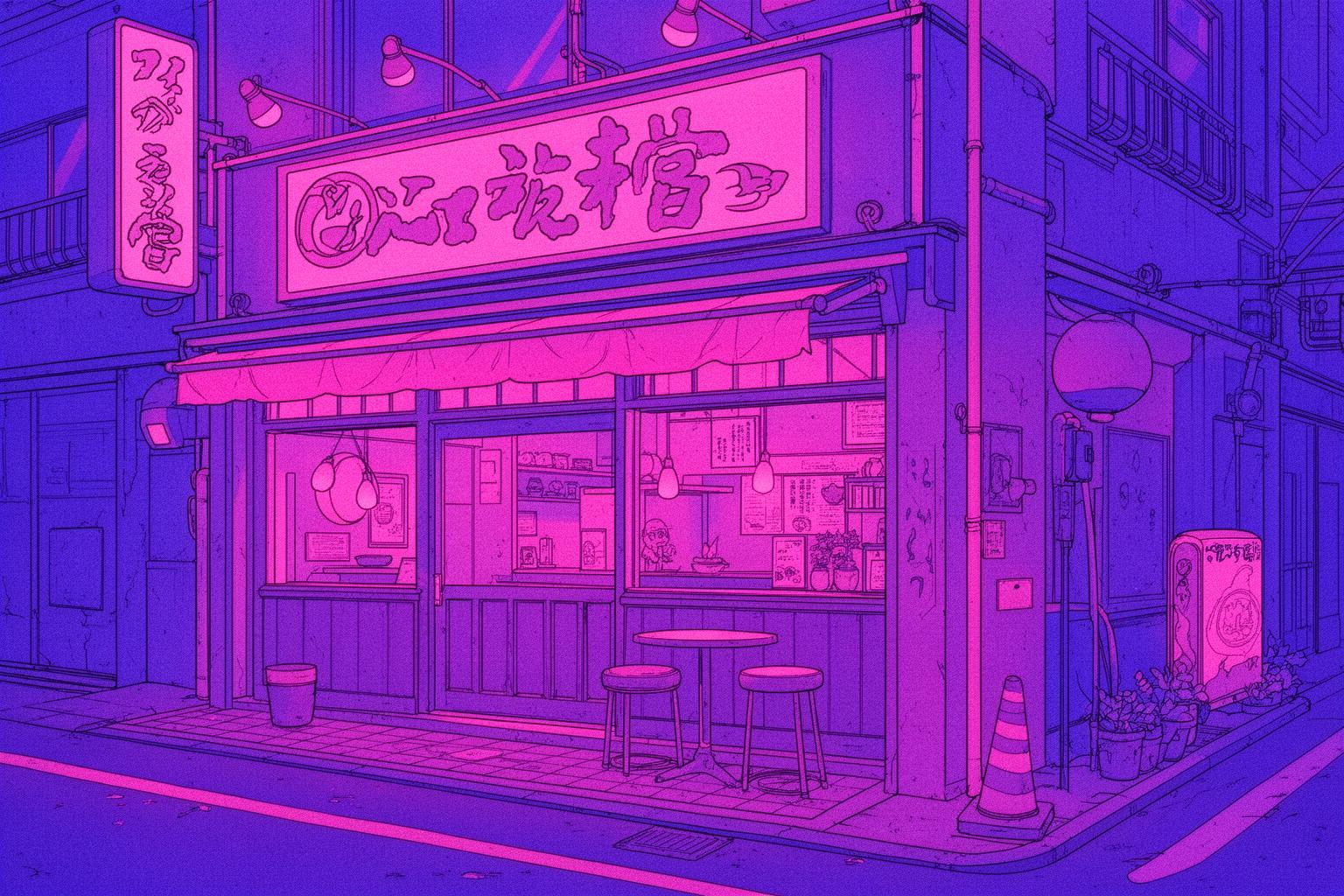

The Vibe Check: What’s a Showa Kissaten, Anyway?

First, let’s clarify the terminology. A ‘kissaten’ (喫茶店) literally means “tea-drinking shop,” but in reality, it’s all about the coffee. Consider it the opposite of a modern, minimalist, third-wave coffee bar. When you enter a Showa-era kissaten, you’re not just walking into a place; you’re crossing a threshold. The atmosphere itself feels different—denser, imbued with the echoes of countless conversations and the rich, dark scent of coffee brewed with meticulous care over decades. The color scheme is nearly always a harmonious blend of browns: dark wooden wall panels, sturdy mahogany counters polished to a glossy finish by frequent use, and amber lamps casting a warm, intimate glow that makes the outside world and its hectic pace seem to fade away.

The seating isn’t meant for quick visits. You’ll find plush, high-backed velvet or leatherette booths that invite you to settle in and linger. The chairs are solid, heavy, and often bear the gentle marks of long-term use. There’s no rush to finish your drink and leave. On the contrary, the whole setting encourages relaxation and extended stays. The background noise isn’t the frantic hiss of a high-volume espresso machine or a stream of algorithm-driven pop music. Instead, you might hear the soft turning of newspaper pages, the delicate clink of a spoon against a ceramic cup, and, most notably, the soundtrack of the Showa era: classical music or American jazz, often spinning from a vintage vinyl collection played on a carefully maintained turntable. The sound is warm, slightly crackling, and deeply soulful. It creates an atmosphere that fosters introspection and quiet reflection. For first-time visitors, the experience can feel almost reverential— a space demanding a special kind of respect, a tranquility that feels earned and precious in today’s noisy world.

Back to the Future: The OG Sustainable Lifestyle

This is where the kissaten story truly reaches the next level. In today’s era of eco-anxiety, we focus on reusable cups and bamboo straws, but the kissaten has been embracing a zero-waste philosophy for nearly a century—not as a marketing strategy, but as a fundamental aspect of its operation. It’s sustainability by default. Let’s explore how.

First, consider the service. When you order coffee, it arrives in a heavy, beautiful ceramic cup, often unique to the shop, which has likely been in use for years, maybe even decades. Your water is served in a genuine glass. Sugar comes in a porcelain bowl with a small metal spoon. Cream is poured from a miniature ceramic pitcher. The stirring spoon and the fork for your cake are solid metal. The small, damp towel you receive to clean your hands, the oshibori, is cloth and laundered for repeated use. Not a single piece of disposable plastic or paper is in sight. This isn’t a choice; it’s the only method. It originates from a time when disposables were a luxury, and high-quality, reusable items were the norm. It reflects a deep respect for objects, the belief that even a simple coffee cup should embody permanence and character.

This philosophy permeates every aspect of the establishment. The furniture—the tables, chairs, and counters—was crafted to endure forever. Made from solid wood rather than cheap particleboard, and upholstered with durable fabrics, repairs are standard: wobbly chair legs are fixed, worn velvet is reupholstered. This stands in direct opposition to fast furniture and throwaway culture. The kissaten owner, the ‘Master,’ views the shop not as a fleeting business, but as a lifelong legacy to uphold. The equipment also tells a story of endurance. The cash register may be a charming, bulky mechanical antique. The siphon coffee makers, with their delicate glass bulbs, are treated with great care and repaired when needed. This embodies the Japanese concept of mottainai—a profound sense of regret over waste. Nothing is discarded lightly. Every item, from the coffee grinder to the lampshade, is valued and cared for.

The menu itself teaches waste reduction. Kissaten menus are usually small and focused, featuring dishes perfected over decades. Ingredients often come from local markets, and the Master carefully estimates how much to purchase. There’s no endless lineup of trendy specials that lead to waste. A classic example is the ‘Morning Service,’ or simply ‘Morning,’ a cherished kissaten tradition. For just a bit more than the price of coffee, you receive a thick slice of toast, a boiled egg, and sometimes a small salad. This tradition likely started as a way to use day-old bread, turning what might have been discarded into a value-added, delicious breakfast. It’s simple, ingenious, and deeply sustainable.

The Master’s Brew: Coffee as a Ritual, Not a Rush

In a kissaten, coffee is more than just a drink; it is the essence of a ritual. The person behind the counter is not merely a barista but the ‘Master’ (マスター), a title bestowed with great respect. Often, this individual has devoted their entire adult life to the singular pursuit of crafting the perfect cup of coffee. Watching a Master at work is like witnessing a finely choreographed performance.

Forget the loud hiss and roar of an espresso machine. The prevailing brewing methods here are far more intentional and meditative. The most visually captivating is the siphon, a glass apparatus reminiscent of something from a chemistry lab. It features two stacked glass globes. Water placed in the bottom globe is heated by a small flame, causing it to rise into the top globe where the coffee grounds await. The Master stirs the blend with a bamboo paddle, a gesture carried out with practiced grace. After a precise amount of time, the heat is removed. As the bottom globe cools, a vacuum forms, drawing the brewed coffee back down through a filter, leaving the spent grounds behind. The process is quiet, mesmerizing, and yields an exceptionally clean, aromatic cup that showcases the subtle flavors of the beans.

Then there is the nel drip, or cloth filter drip, regarded by many aficionados as the pinnacle of pour-over coffee. The Master employs a flannel filter held by a wire ring. The process is painstakingly slow. Hot water is poured over the grounds in an impossibly thin, steady stream. Brewing a single cup can take several minutes. The Master’s focus is unwavering; every movement economical and exact, refined through tens of thousands of repetitions. Unlike paper, the cloth filter permits more coffee oils to pass through, producing a cup with a distinctively rich, velvety body and a smooth, rounded flavor profile that other methods cannot replicate. The care devoted to the cloth filter is itself a ritual; it is meticulously cleaned after each use and stored in cold water to prevent oxidation.

The coffee beans themselves are often a source of pride. The typical kissaten roast is dark and intense, reflecting a flavor profile popular during the Showa era. It offers a bold, nostalgic taste—low in acidity with hints of dark chocolate, caramel, and a pleasant smoky bitterness. Some legendary kissaten, such as Ginza’s Café de l’Ambre, take this even further by specializing in aged coffee. Green coffee beans are aged for years, sometimes decades, much like fine wine. This aging process softens the acidity and develops a deeply complex, profound flavor that is smooth, sweet, and truly unique. A cup of 20-year-old aged coffee is more than just a drink; it is a taste of history, a liquid time capsule.

More Than a Meal: The Classic Kissaten Menu

While coffee takes center stage, the food menu at a kissaten plays a crucial role in its charm. These dishes aren’t elaborate chef-driven creations; they are straightforward comfort food, prepared with understated precision. The menu is a nostalgic trip back to the flavors of Showa-era Japan, when Western dishes were adapted with a distinctively Japanese flair.

The unquestioned champion of kissaten meals is Napolitan spaghetti. Forget authentic Italian pasta—this is a deliciously inauthentic dish of spaghetti stir-fried with onions, green peppers, mushrooms, and slices of sausage or ham, all coated in a sweet and tangy ketchup-based sauce. Originating in post-war Japan, it was an effort to recreate a Western dish using accessible ingredients. Though it might sound unusual, one bite reveals its charm: savory, sweet, and profoundly satisfying, the ultimate Japanese comfort food. It’s often served sizzling on a cast-iron plate, sometimes topped with a fried egg.

For a lighter choice, there’s the iconic tamago sando (egg salad sandwich) or mix sando (mixed sandwich). The bread is always impossibly soft and fluffy Japanese milk bread (shokupan), with the crusts meticulously removed. The fillings are simple yet flawless: creamy egg salad or layers of ham, cucumber, tomato, and lettuce. These sandwiches are crafted with geometric precision and cut into neat triangles or rectangles, turning a simple sandwich into an art form.

Then there are the sweets. The Melon Cream Soda is an iconic sight in the kissaten world. It’s a glass of vividly bright green melon-flavored soda topped with a perfect scoop of vanilla ice cream and often crowned with a maraschino cherry. It’s pure bubbly sugary delight, a drink that instantly conjures childhood memories, even if not your own. Another beloved classic is Pudding a la Mode, a firm caramel-topped custard pudding (purin) served in an elegant glass dish, surrounded by a colorful assortment of canned fruits, a swirl of whipped cream, and a wafer cookie. It’s a dessert of pure, nostalgic joy.

And we mustn’t overlook the toast. A thick slice of shokupan, toasted to a golden crust outside while remaining pillowy-soft inside, is a kissaten essential. The bata tosuto (butter toast) is a simple indulgence, but many shops offer their own specialties. In Nagoya, famed for its ‘Morning’ culture, the Ogura Toast reigns: a thick slice topped with a generous spread of sweet red bean paste (anko) and a pat of butter. The combination of sweet, salty, and creamy is nothing short of revelatory.

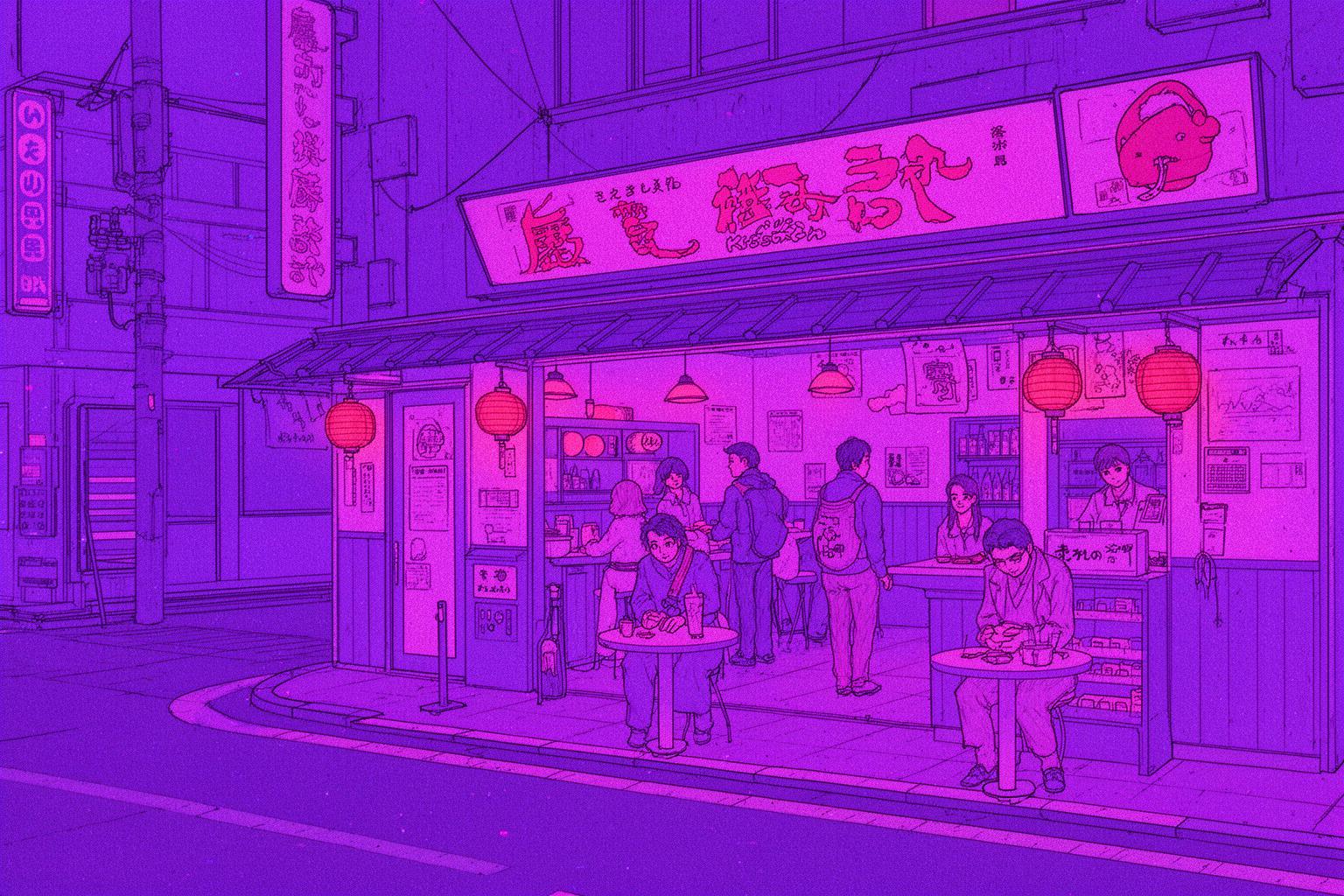

A Sanctuary in the City: The Social Role of Kissaten

A kissaten has always been more than just a place to get a caffeine fix. It serves as an essential ‘third place,’ a neutral zone between the demands of home and work. For generations, these establishments have acted as the unofficial community hubs of their neighborhoods. Each kissaten possessed its own unique character and clientele, fulfilling a particular social role.

For the countless salarymen, Japan’s white-collar workers during the economic boom, the kissaten was an indispensable refuge. It was a spot to smoke a cigarette (many kissaten still permit smoking, a remnant of a past era), read the morning paper before heading to the office, or pass the time between meetings. It provided a space to unwind, a quiet bubble where workplace hierarchies were temporarily set aside. The Master often served as a silent bartender, a familiar figure who knew your usual order and offered a stable place of quiet comfort in a demanding world.

They were also hubs of creativity. In areas like Tokyo’s Jinbocho, the renowned book district, kissaten became informal offices for writers, editors, manga artists, and scholars. Over countless cups of dark coffee, novels were penned, manuscripts refined, and intellectual debates flourished. The peaceful, focused environment supported deep work, and the presence of other creative minds fostered a vibrant intellectual energy. Many notable works of Japanese literature originated at a small table in a smoky kissaten.

For students, kissaten offered quiet spots to study for exams, away from home distractions. For young couples, they provided a respectable and intimate venue for dates. They also served as the traditional setting for an omiai, a formal meeting between potential marriage partners, providing a neutral and dignified atmosphere. A kissaten is a stage on which the subtle, quiet dramas of everyday life have unfolded for decades. This is why it should not be treated like a modern co-working space. Many traditional kissaten lack Wi-Fi and have few, if any, power outlets. The unspoken rule is to disconnect from the digital world and engage with the physical space, your companion, or your own thoughts.

Finding Your Time Capsule: A Guide to Kissaten Hopping

So, you’re captivated by the vibe and eager to experience it for yourself. Great. Discovering an authentic Showa-era kissaten can be part of the journey. They’re often hidden away on side streets, down narrow staircases leading to basements, or on the second floor of unassuming buildings. Their entrances tend to be modest, marked by a faded sign with elegant calligraphy or a small, charmingly retro neon sign.

Certain neighborhoods are goldmines. In Tokyo, Jinbocho is a must-see, where cafes are nestled among hundreds of secondhand bookstores. Shinjuku, despite its futuristic chaos, conceals incredible basement kissaten that feel like secret hideaways. Ginza, the city’s upscale district, hosts some of the most famous and refined establishments. In Kyoto, elegant kissaten are tucked away in shopping arcades like Teramachi or near the university, places that have welcomed students and professors for generations. Asakusa, with its old-Tokyo ambiance, is another favorite spot.

Once you find a promising place, keep these points of etiquette in mind. First, be observant. If the space is small and quiet, with only a few elderly patrons reading, it’s a signal to keep your voice low. Speak softly. Second, order at least one item per person. You’re paying not just for the drink but also for the time and the seat. Lingering is welcome, but occupying a seat without ordering is not. Third, be prepared for smoking. Although Japan’s smoking laws have tightened, many old kissaten have exemptions or designated smoking areas, and the faint, sweet aroma of old tobacco often adds to the atmosphere. If you’re sensitive to smoke, keep this in mind. Finally, and most importantly, put your phone away. At the very least, avoid loud calls or watching videos. The true charm of a kissaten lies in its analog nature. Read a book. Write in a journal. Watch the master brew coffee. Have a quiet conversation. Just be present.

A Few Legendary Spots to Get You Started

While the joy lies in discovering your own secret spot, a few legendary kissaten serve as perfect introductions to this world. They are famous for good reason and live up to the expectations.

In the heart of Tokyo’s Ginza, you’ll find Café de l’Ambre. This is not a place for casual conversation; it is a temple dedicated to coffee. Open since 1948, it is run with monastic devotion by a staff committed to the art of aged coffee. The interior is dark, narrow, and solemn. The menu is an encyclopedic list of coffees, organized by year of origin and roast. Ordering a cup of coffee from the 1970s is a profound experience, a taste of a world that no longer exists. It is an intense, unforgettable coffee pilgrimage.

For something more bohemian and eclectic, head to Jinbocho to find Saboru. In fact, there are two: Saboru and Saboru 2. Saboru is a cave-like, subterranean space that feels like a mountain lodge, with rough-hewn wooden logs, totem poles, and thousands of handwritten notes from patrons plastered on the walls. It’s chaotic, cluttered, and incredibly cozy. Next door, Saboru 2 is slightly more conventional, serving meals such as the famous Napolitan. Visiting both is essential to fully experience the wonderfully quirky atmosphere.

Over in Kyoto, a visit to Smart Coffee in the Teramachi Shopping Arcade is a rite of passage. It has been serving locals since 1932. The ground floor offers a bustling, classic kissaten atmosphere, while the upstairs restaurant serves Western-style Japanese dishes. They are best known for their hotcakes (Japanese pancakes), which are thick, fluffy, and served with butter and syrup. The coffee is a classic dark roast, a perfect, no-nonsense cup that has stood the test of time.

Also in Kyoto is the stunning François Kissa Shitsu. Established in 1934, its beautiful baroque-style interior was designed to resemble a luxury cruise liner. With its domed ceiling, dark wood, stained-glass windows, and red velvet chairs, it feels like stepping into a grand European café of a bygone era. The space is so historically significant that it has been designated one of Japan’s Registered Tangible Cultural Properties. It’s a place to feel elegant and sophisticated while savoring a Viennese coffee.

The Enduring Legacy: Why Kissaten Still Slap

In a world that values speed, efficiency, and novelty above all else, the Showa-era kissaten quietly resists. It stands as a tribute to slowness, quality, and lasting presence. It’s a brilliant business model when you consider it: craft a space so inviting and a product so exceptional that people choose to linger, disconnect, and savor the moment.

These cafes go beyond mere nostalgia. They serve as a living, breathing guide to a more sustainable and mindful lifestyle. They teach the importance of reusing, repairing, and treasuring what we own. They remind us that communities are nurtured in quiet spaces, through face-to-face interactions, not just digital connections. They show that a lifelong dedication to craft produces results no machine or algorithm can match. The kissaten philosophy—the slow drip, the carefully selected cup, the seat made for reflection—is a remedy for the burnout and disposability of modern life. It’s a whole vibe, a way of living. So next time you’re in Japan, skip the global chains. Look for a worn sign, push open a heavy wooden door, and step back in time. Order a coffee, and let time slow down. IYKYK. It’s an experience that truly, undeniably slaps.