Yo, what’s up, world travelers! It’s your boy Hiroshi Tanaka, a 40-something local guide, coming at you straight from the heart of Japan. Forget the neon chaos of Tokyo and the packed streets of Kyoto for a sec. We’re going somewhere deeper, somewhere that hits different. I’m talking about Koyasan, or Mount Koya, in Wakayama Prefecture. This ain’t just a mountain, my friends. This is the spiritual headquarters of Shingon Buddhism, a UNESCO World Heritage site, and legit one of the most soul-stirring places on the entire planet. It’s a place where you can disconnect from the Wi-Fi and reconnect with yourself. The main event? Staying in a shukubo, a real, functioning Buddhist temple. It’s not just a bed for the night; it’s a full-on cultural immersion, a chance to live like a monk, eat like a monk, and find a level of peace you didn’t even know you were looking for. This experience is, in a word, epic. It’s a chance to quiet the noise, breathe in the ancient cedar-scented air, and feel the pulse of a thousand years of history. Prepare to have your mind blown and your spirit totally refreshed. This is the real Japan, the one that whispers secrets through the rustling leaves of ancient forests. So buckle up, because we’re about to ascend to a whole new level of travel.

The Journey is the Destination: Getting to Cloud Nine

First and foremost, getting to Koyasan is part of the enchantment—it’s a pilgrimage in itself. You’ll most likely begin at Osaka’s Namba Station, a bustling urban maze filled with noise and energy. From there, you’ll board the Nankai Koya Line. Here’s a tip: splurge a bit on the Limited Express train. It offers reserved seating and large windows that provide a perfect view as the city fades into quiet suburbs, then lush green valleys and rolling hills. The train meanders through the countryside, following rivers and slipping into tunnels. The final section is steep; you can sense the train working hard, climbing steadily, carrying you away from everyday life. The journey ends at Gokurakubashi, meaning “Paradise Bridge Station”—and the name isn’t an exaggeration. At this point, you switch to a cable car, where the true ascent begins. The ride is steep, gripping the mountainside at nearly an impossible angle. As you’re pulled up through dense forest, the air shifts, becoming cooler, fresher, filled with the scent of cedar and damp earth. You’re leaving the world below and entering a realm of clouds and serenity. When you disembark at the top, you’ve arrived: the sacred plateau of Koyasan, roughly 800 meters above sea level. The temperature drops noticeably, and the silence envelops you immediately. It’s a different world—a sacred bubble suspended between heaven and earth. This journey perfectly sets the tone for the spiritual renewal that awaits.

Shukubo 101: Your Temple Sweet Temple

So, what exactly is a shukubo? Let’s break it down. The term means “temple lodging.” Initially, these were simple accommodations for tired pilgrims who had walked for days to reach Koyasan. Nowadays, they welcome everyone, providing a unique glimpse into monastic life. But to be clear: this isn’t a ryokan or a hotel. You are a guest in a living, breathing religious institution. The people you meet are monks, not concierges. The rules exist to preserve the sanctity and routine of the temple. This is the essence of the experience—stepping into their world, not expecting them to fit into yours.

Koyasan has over fifty shukubo, each with its own history, atmosphere, and special features. Some are large and grand, boasting centuries of history, priceless art, and gardens crafted by master designers. Others are smaller and more intimate, offering a quieter, more personal stay. Choosing the right one is essential for your trip. Some, like Eko-in or Fudoin, are popular and provide English-speaking staff and guided activities such as night tours of the Okunoin cemetery. Others may have stunning painted screens (fusuma) or a notable connection to a famous historical figure. My advice is to research on the official Koyasan Shukubo Association website. Consider what you want: a renowned garden? A chance to witness a Goma fire ritual? A modern room with a private bathroom? All of this is available, but you must book—and I mean book well in advance, especially for the cherry blossoms in spring and the breathtaking colors of autumn. Those seasons are fiercely competitive for rooms, so plan ahead!

Upon arrival at your chosen temple, check-in is a practice in mindfulness itself. You’ll slide open heavy wooden doors, step into the cool, incense-scented entrance, and be welcomed by a monk. They’ll guide you to your room, a peaceful space of woven tatami mats, minimalist decoration, and sliding paper doors that may open onto a perfectly tended moss garden. There’s no TV, no noisy mini-fridge, just the essentials: a low table, some cushions (zabuton), and a closet with your futon bedding and a yukata (a simple cotton robe). This is your sanctuary. The simplicity is intentional. It invites you to slow down, to notice the light filtering through paper screens, the tolling of a distant bell, the soft rustle of leaves in the garden. You’ll also receive a schedule briefing: dinner time, morning prayers, and curfew. Yes, there is a curfew, usually around 9 PM. Koyasan isn’t a nightlife spot; it’s a space for reflection and rest.

Shojin Ryori: Feasting for the Soul

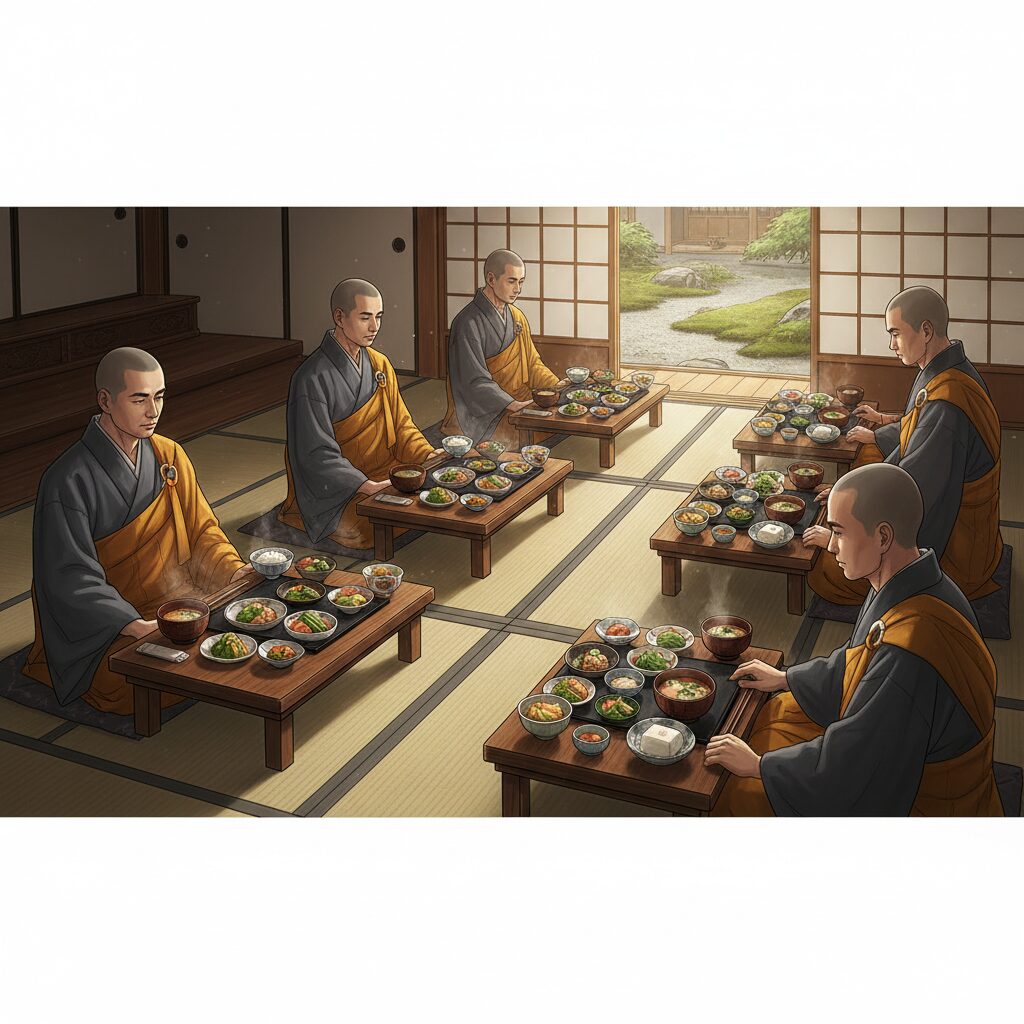

Let’s discuss one of the absolute highlights of any shukubo stay: the food. You’ll be enjoying Shojin Ryori, traditional Buddhist vegetarian cuisine. If you assume vegetarian food is dull, get ready to be pleasantly surprised. This cuisine is both culinary art and spiritual practice combined. Shojin Ryori follows the Buddhist principle of not taking life, so it contains no meat or fish. It also excludes strong ingredients like garlic and onion, which are thought to stimulate the senses and disrupt meditation. The emphasis is on balance, simplicity, and enhancing the natural flavors of seasonal vegetables, tofu, and mountain plants.

Dinner is an event in itself. It’s usually served in your room on a low lacquer table. A monk will present a series of small, beautifully arranged dishes. It’s a feast for the eyes before you even taste a bite. Among the offerings, you’ll likely find goma-dofu, a Koyasan specialty. This creamy, savory sesame tofu has a panna cotta-like texture—simply divine. There may also be delicate vegetable tempura, simmered wild vegetables, various types of tofu (fried, boiled, in soup), tangy pickles (tsukemono), a clear, subtle soup, and naturally, a bowl of perfect white rice. The philosophy behind the meal follows the rule of five: five colors (white, black, red, green, yellow), five flavors (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, umami), and five cooking methods (raw, simmered, fried, steamed, grilled). This approach ensures a meal that is not only nutritionally balanced but also harmonizes body and mind. The flavors are gentle, clean, and deeply satisfying. You eat slowly and mindfully, savoring each ingredient. It’s more than just dinner; it’s a meditation on a plate, and you’ll be amazed at how full and nourished you feel afterward.

Breakfast is a similar experience, served early after the morning ceremony. It’s usually simpler but equally delicious, often featuring rice porridge (okayu), miso soup, pickled plums (umeboshi), and other small vegetable dishes. It’s the perfect gentle way to begin a day of spiritual exploration.

The Heart of the Experience: Morning Chants and Fire Rituals

This is it—the main event, the very reason you rose before dawn despite your body’s plea for more sleep. The morning ceremony, or Otsutome, serves as the spiritual cornerstone of the shukubo experience. A monk will gently rouse you before sunrise. After donning warm clothes (since temple halls can be especially cold in winter), you’ll quietly make your way in the pre-dawn light to the temple’s main hall (hondo). The air is thick with the aroma of aged wood and countless burning incense sticks. You’ll kneel on a cushion as the monks enter, their robes swishing softly, and take their places before the altar.

Then it begins—the chanting. It starts as a low, resonant hum that builds into a powerful, rhythmic chorus of sutras. The sound fills the room, vibrating through the wooden floors and deep into your bones. Understanding the words isn’t necessary to feel their impact. It’s a primal, ancient sound that has resonated in these halls for centuries. You can close your eyes and let the vibrations wash over you. It’s a profoundly moving, goosebump-inducing experience that links you to the long lineage of devotion sustaining Koyasan. It’s the ultimate ASMR—a sound bath for the soul.

Some temples also conduct a Goma fire ritual, which takes intensity to another level. In this esoteric ceremony, the head priest builds a sacred fire in a special hearth. He chants mantras while feeding cedar sticks—symbolizing human desires and worldly attachments—into the roaring flames. The fire is believed to purify negative energies and carry prayers to the heavens. The heat is intense, the drumming hypnotic, and the priest’s chanting both powerful and mesmerizing. Watching the flames leap and dance in the dimly lit hall is an unforgettable, multi-sensory spectacle. It feels ancient, mystical, and deeply potent. Taking part in these morning rituals is more than just an activity; it’s the very essence of the shukubo experience. It’s what elevates your stay from a simple overnight visit into a true spiritual retreat.

Wandering the Sacred Grounds: Okunoin and the Garan

Your shukubo serves as your home base, but the true magic of Koyasan reveals itself as you explore its sacred sites. The two absolute must-see destinations are the Okunoin cemetery and the Danjo Garan temple complex. They symbolize the beginning and the end, the heart and soul of this mountain.

Okunoin: A Walk Among Spirits

Okunoin is more than just a cemetery; it is Japan’s largest and most sacred resting place. A two-kilometer path meanders through a forest of colossal, ancient cedar trees, some over a thousand years old. Along the path stand over 200,000 tombstones and memorials belonging to people from all walks of life, from emperors and feudal lords to humble monks and ordinary individuals. You’ll find memorials to some of the most famous figures in Japanese history, such as the warlords Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The stones are blanketed in thick moss, giving the entire area an ethereal, otherworldly atmosphere. Sunlight filters through the towering canopy, dappling the path in a constantly shifting pattern of light and shadow. It’s not eerie; it is deeply peaceful and awe-inspiring. You feel as if you are walking through time itself.

The path ends at the Gobyobashi Bridge, which marks the boundary between the secular world and the sacred inner sanctuary. You bow before crossing as a sign of respect. Beyond the bridge lies the Torodo Hall, or Hall of Lanterns. Inside, over 10,000 lanterns donated by devotees hang in dense rows, perpetually lit. Two lanterns are said to have been burning continuously for over 900 years. The shimmering golden light is breathtaking. Behind this hall stands the Gobyo, the mausoleum of Kobo Daishi, founder of Shingon Buddhism. It is believed that he is not dead but remains in a state of eternal meditation, praying for the peace and salvation of all living beings. The air here is thick with reverence. You can sense the weight of centuries of faith. It is a place of immense spiritual power.

For a truly exceptional experience, take the guided night tour of Okunoin, often offered by temples such as Eko-in. Walking the same path under the light of stone lanterns, with a monk as your guide sharing stories and legends, creates a completely different atmosphere. The forest becomes a realm of mystery and magic. It is an absolute must-do.

Danjo Garan: The Heart of the Doctrine

If Okunoin is Koyasan’s soul, the Danjo Garan complex is its heart. This is where Kobo Daishi first established his monastic center. It is a sprawling complex of halls and pagodas forming a three-dimensional mandala, representing the cosmic Buddhist universe. The most striking structure is the Konpon Daito, a massive, two-tiered pagoda painted in vibrant vermilion. It stands out against the green forest and blue sky. Step inside, and you’ll find a stunning interior adorned with statues centered around the cosmic Buddha, surrounded by pillars painted with Bodhisattvas. It is a dazzling, symbolic space designed for esoteric rituals and meditation.

Nearby is the Kondo, or Main Hall, where major ceremonies take place. Though rebuilt multiple times over the centuries due to fires, it remains the central worship hall of the Garan. You can also visit the Miedo (Founder’s Hall), a sacred space housing a portrait of Kobo Daishi, and the Fudodo, the oldest surviving building on Koyasan—a national treasure dating from the 12th century. As you wander through the Garan, you get a sense of Kobo Daishi’s grand vision—to create a perfect training ground for his esoteric Shingon doctrine, far from the political distractions of the capital.

Deeper Dives: Kongobuji and Beyond

For those eager to explore further, a visit to Kongobuji Temple is a must. This temple serves as the head temple of Koyasan Shingon Buddhism and functions as the administrative hub for thousands of Shingon temples throughout Japan. The expansive complex features rooms adorned with stunning painted screens (fusuma) created by artists from the renowned Kano school. Among its most remarkable highlights is the Banryutei Rock Garden, the largest in Japan, which portrays two dragons rising from a sea of clouds using massive granite stones and carefully raked white sand. You can also tour the temple’s huge kitchen, with its enormous hearths and cauldrons, offering insight into the scale of operations needed to feed hundreds of monks and pilgrims.

For art and history enthusiasts, the Reihokan Museum is a true treasure. It houses thousands of artifacts from the Koyasan temples, including Buddhist statues, paintings, mandalas, and sutras. Many of these pieces are designated National Treasures, providing a captivating visual journey through the mountain’s rich history and artistic heritage.

Don’t overlook the lesser-known paths. The Nyonin-do, or Women’s Hall, is located at one of the old entrances to Koyasan. Historically, women were prohibited from entering the sacred mountain precincts, allowed only to worship from these peripheral halls—a restriction that was lifted in 1872. Visiting the Nyonin-do offers a poignant reminder of this past and stands as a testament to the devotion of the women who made their pilgrimages here despite the limitations. Additionally, there are scenic hiking trails, such as the Women Pilgrims’ Route, which encircle the mountain and provide breathtaking views.

Practical Intel and Pro Tips

Alright, let’s dive into the details. Here’s some advice to help make your trip smooth and stress-free.

Timing is Everything

When is the best time to visit? Honestly, Koyasan is stunning all year round, but each season has its own unique atmosphere. Spring (April-May) features cherry blossoms but also attracts crowds. Summer (June-August) offers a lush, green retreat from the lowlands’ intense heat, though it can be rainy. Autumn (late October-November) is the peak season for good reason: the fall foliage is absolutely breathtaking, transforming the mountain into a vibrant palette of reds, oranges, and yellows. However, it’s very crowded, and you’ll need to book accommodation and transport months, if not a year, ahead. Winter (December-February) is my personal favorite secret. It’s the quietest time of year, with the mountain often draped in pristine white snow. The silence is deep, the air crisp, and seeing the temples and Okunoin covered in snow is a magical, almost mystical experience. Just be prepared—it’s extremely cold, so bring serious thermal gear.

Pack Smart

Whenever you visit, pack layers. Temperatures on the mountain can be much cooler than in the cities and can shift quickly. Comfortable walking shoes are essential; you’ll be walking extensively on stone paths and wooden temple floors. Since you’ll be removing your shoes frequently when entering temples, opt for shoes that are easy to slip on and off. Bringing an extra pair of thick socks is wise, as wooden floors can be chilly. Cash remains king in many smaller shops, so carry some yen. Most importantly, bring an open mind and a respectful attitude—remember, you’re a guest in a deeply sacred place.

Navigating the Mountain

After arriving at Koyasan Station by cable car, you’ll need to take a bus into the town center. The bus system is excellent and covers all the major sites. I strongly recommend purchasing a day pass, which allows unlimited rides and makes exploring much easier. The town is relatively compact and walkable, but key sites like Okunoin, the Garan, and Kongobuji are spread out, so the bus will be your best ally.

Final Thoughts: The Koyasan Effect

A trip to Koyasan is more than just a vacation. It’s a journey inward—a chance to step away from the hectic pace of modern life and into a rhythm that has persisted for over 1,200 years. At the core of this experience is the shukubo stay. It’s not about luxury, but about simplicity, mindfulness, and active participation. It’s about waking before dawn in quiet, feeling the ancient chants resonate within you, savoring food that nourishes both body and spirit, and walking through a forest where the air is alive with spirituality. You leave Koyasan transformed—calmer, more grounded, and filled with a renewed sense of wonder. It’s a place that touches your soul and lingers long after you’ve descended the mountain. So go ahead—take the pilgrimage, find your flow, and let the magic of Mount Koya work its wonders on you. It’s a spiritual glow-up you’ll never forget. Peace out.