The Sun Dips, The Vibe Shifts

The atmosphere in Takaoka shifts as the sun fades away. Seriously. One moment, you’re all about that Great Buddha vibe, capturing photos of Japan’s third-largest bronze statue, soaking in the steady, daytime energy of a city founded on skill and persistence. The next, the light turns warm and golden, highlighting the edges of the tiled roofs in Kanayamachi, and the entire mood flips. Day-trippers disappear, catching the last trains out, and Takaoka breathes out. In that quiet exhale, the city’s true spirit begins to emerge. This isn’t Tokyo, friends. It’s not Osaka. It’s something completely different. It’s a low-key, IYKYK kind of magic, a nightlife that doesn’t shout for attention but quietly calls your name from behind a dimly lit sliding door. It’s less about the party and more about the poetry. It’s a vibe for the soul.

Most visitors come for the visible history—the latticed windows, Zuiryuji Temple, the entire historical VIP district. But trust me, the history you can feel, the one that’s alive and pouring drinks, is the story you want to be part of. It’s a scene hidden in the shadows of its own heritage, a network of small bars and izakayas that form the living, beating heart of this old castle town. So, if you’re over the neon chaos and craving something genuine, stick around after sunset. Let’s get lost in the real Takaoka.

The Lantern’s Call: A Walk into Yesterday

Night doesn’t simply fall in Takaoka; it seeps in slowly. It rises from the cobblestones and spills out from the alleyways. My first true experience of this was in Yamachosuji, the old merchant district. By day, it’s impressive, no doubt. The large, sturdy storehouses, the kura, stand like stoic old men, their black-and-white walls bearing witness to centuries of wealth and trade. But by night, they change. They become monoliths, silent guardians. Streetlights cast long, skeletal shadows that flicker across the plastered walls. The silence is deep. It’s the kind of quiet so intense it almost hums. You hear the scuff of your own shoes, the whisper of wind funneling between the buildings. It feels like slipping through a crack in time, like wandering a museum after hours—except the exhibits are alive.

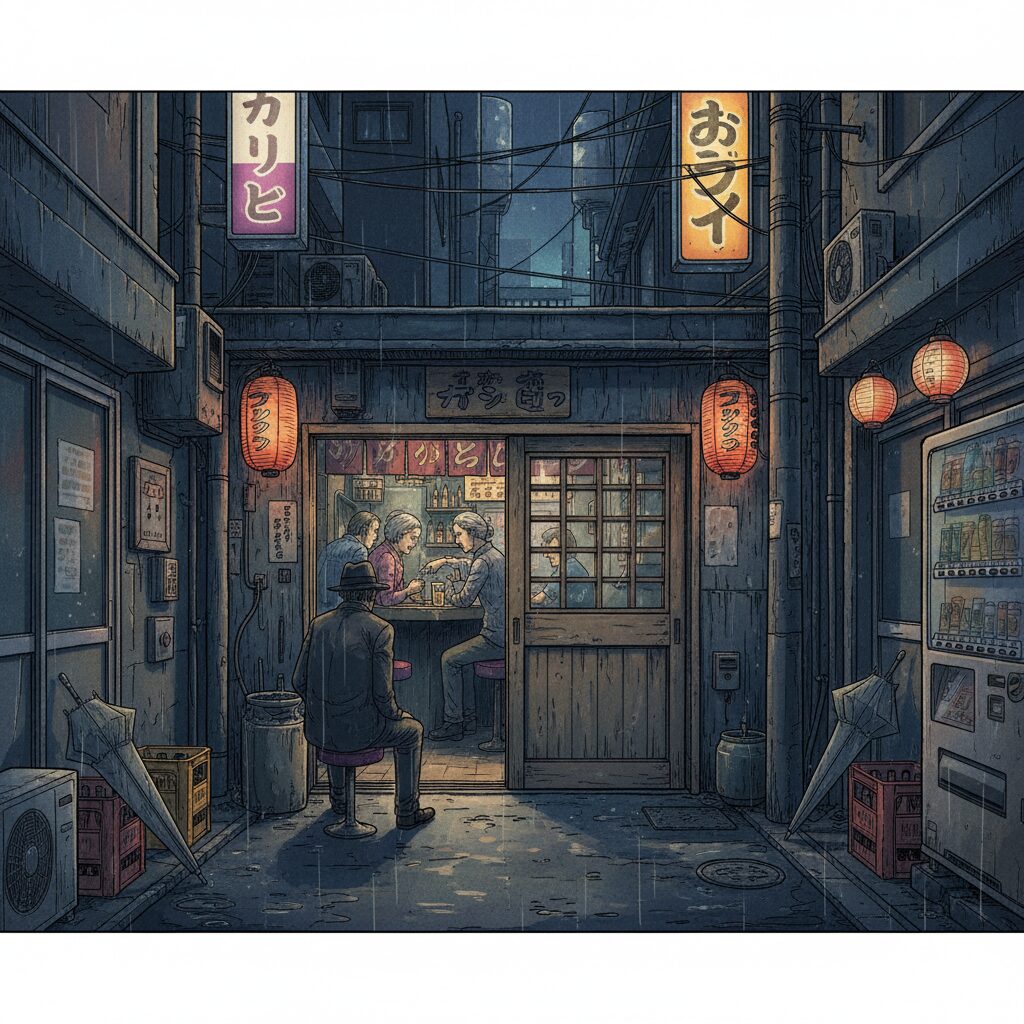

This is where the hunt begins. You’re not searching for signs in English. You’re not chasing flashing lights or pounding bass. You’re seeking a single, glowing orb: an aka-chōchin, a red paper lantern hanging outside an unassuming wooden facade. It’s the bat signal for good times in Japan, a beacon that says, “Come in, the sake’s warm and the company is welcoming.” Or maybe it’s a simple noren, a short cloth curtain, fluttering in the doorway, offering just a glimpse of the warmth inside. Each one is a gateway. Each one a promise.

I remember walking these streets for what felt like hours, camera in hand, not even taking pictures, just soaking it all in. The air was crisp, carrying the faint, savory scent of grilled something-or-other from a distant kitchen. The sky was a deep, bruised purple—the kind you only see far from the light pollution of big cities. It felt sacred, almost. I passed by houses with their lights on, catching fleeting glimpses of families watching TV, their lives unfolding in quiet, domestic moments. It made me feel like a ghost, an observer drifting through a world that wasn’t quite mine but, for a brief moment, was letting me in. And then I saw it. A tiny, unadorned wooden door, almost lost in the shadow of a grand old merchant house. A single, perfectly round lantern glowed beside it, casting a soft, inviting light on the dark wood. There was no sign, no name to read. Just the light. Just the promise. My heart did a little kickflip. This was it. This was the place.

Sliding the Door: The World of the Snack Bar

Taking a deep breath, I slid open the door. The sound it made—a soft, wooden creak—seemed to linger in the quiet street. Inside felt like a world away from the dark, silent lane I had just left. It was small, with maybe eight seats along a long, polished cypress counter. The atmosphere was warm, filled with the low murmur of conversation, the clink of ice in glass, and the scent of whiskey and aged wood. Behind the counter stood a woman who appeared to be in her late sixties, her hair perfectly styled, a gentle smile on her lips. She was the “mama-san,” the heart and soul of the place—the queen of this tiny realm. Welcome to the world of the sunakku, the Japanese snack bar.

Let’s be clear: a snack bar isn’t about snacks. It’s a cultural institution—a neighborhood living room, a confessional, a stage for amateur karaoke stars. It’s the original social network. Shelves lined the walls, filled with countless bottles of whiskey and shochu, each tagged with a handwritten paper label in Japanese. These were “keep bottles,” a system where regulars buy a full bottle and the mama-san stores it for their next visit. It’s a symbol of belonging. Have a bottle, have a home here.

I took a seat at the counter’s end, feeling like a massive, awkward foreigner. The three other patrons, men in their fifties and sixties, turned to look at me—not with suspicion, but gentle curiosity. The mama-san smiled, bowed slightly, and handed me a warm, damp oshibori towel. No menu was offered. She simply asked, “Nomimono?” What will you drink? I chose the classic highball. Watching her make it was pure theater—the precise amount of ice, the practiced pour of Suntory Kakubin, the high-pressure fizz of soda, the quick stir, the lemon slice. A ritual perfected through thousands of repetitions. It was art.

The first sip was electric—crisp, cold, perfect. The old men nodded at me. One, with a weathered face and kind eyes, raised his glass. “Kanpai,” he said, the universal word for “cheers.” I raised mine in return. “Kanpai.” Just like that, the ice broke. Language was a barrier, definitely—my Japanese was basically non-existent, and their English was limited to a few learned words from school decades ago. But we found a way. Using translation apps, gestures, and plenty of smiles and laughter, we connected. They wanted to know where I was from, what brought me to Takaoka. They were proud of their city, its bronze work, its history. The mama-san occasionally chimed in, correcting mistranslations or adding context, all while effortlessly refilling drinks and preparing small plates of otsumami—appetizers served with the seating charge, or otoshi. That night it was hijiki seaweed salad and slices of pickled daikon. Simple, but delicious.

After a while, the karaoke machine in the corner, which I hadn’t noticed, flickered on. One of the men, who had been quiet until then, picked up the microphone. He transformed—his shy demeanor vanished as he belted out an enka ballad, a dramatic, soulful Japanese folk song, with the passion of a professional. His friends clapped along, and the mama-san watched with maternal pride. It was raw, real, and beautiful. This wasn’t a show for tourists. This was life. This was their community, and for a few hours, they let me be part of it. The cover charge, which sometimes surprises foreigners, suddenly made perfect sense. You’re not just paying for a seat; you’re buying a ticket to the show. You’re renting a little piece of home for the evening. When I finally left, bowing deeply to the mama-san and my new friends, I stepped back into the silent street feeling as if I’d been let in on the city’s most beautiful secret.

Fueling the Soul: An Izakaya Interlude

One does not survive on highballs alone, and Takaoka’s nightlife is just as much about the food as it is the drinks. The next stop was an izakaya, the Japanese counterpart to a gastropub. Again, the search was part of the excitement. I wandered toward the area around Suehirocho, a slightly more modern yet still incredibly charming entertainment district. The streets here were livelier, with more glowing lanterns and signs of life. I found a promising spot—another wooden sliding door, the sound of laughter spilling out, and the irresistible aroma of something delicious grilling over charcoal.

Entering an izakaya is a full sensory experience, in the best way. It’s loud, steamy, chaotic, and wonderful. The air is thick with grill smoke and the lively energy of people relaxing after a long day. I grabbed a seat at the counter, always the prime spot. It’s front-row seating for the culinary performance. The taisho, the kitchen master, moved with frenetic grace, his hands a blur as he sliced sashimi, skewered chicken, and plated dishes with incredible speed and precision.

Takaoka is in Toyama Prefecture, located right on the Sea of Japan. And let me tell you, that bay is a treasure trove. The menu celebrated this local bounty. This is where you go deep. I began with shiro-ebi, the famous Toyama white shrimp. Served raw, they were a delicate, glistening heap of tiny, sweet jewels. They tasted like the ocean itself—clean and incredibly sweet. Then came the hotaru-ika, or firefly squid, another local legend, known for its bioluminescence in the bay. Boiled and served with vinegared miso, the flavor was intense—a briny, funky, complex bite unlike anything I’d ever had. It was a flavor 100% Toyama, a true taste of the place.

Of course, you can’t visit an izakaya without trying yakitori, grilled skewers. I pointed to a few items on the grill: negima (chicken and leek), tsukune (chicken meatball), and kawa (crispy chicken skin). Each skewer came off the charcoal grill smoky, perfectly seasoned, and utterly addictive. To wash it all down, I dove into the local sake. Toyama boasts some incredible breweries. I asked the taisho for an osusume, a recommendation. He poured me a glass of Masuizumi, a local brand. It was crisp, clean, and slightly fruity, cutting through the richness of the grilled food perfectly. Seeing my appreciative nod, he poured me another, richer and more full-bodied, to pair with buri daikon—yellowtail simmered with daikon radish until tender enough to fall apart. The fish was rich and oily, while the radish had absorbed all the savory, sweet soy-based broth. It was comfort food on a whole new level. Soul food. Sitting there, surrounded by the happy chatter of locals, eating food pulled from waters just miles away, drinking sake brewed from local rice and mountain water, I felt a deep connection to this place. This wasn’t just dinner. It was a conversation with Takaoka.

The Art of the Pour: A Quieter Note

After the vibrant chaos of the izakaya, I found myself yearning for a return to quiet. My feet, as if guided by their own will, led me down another narrow alley, barely wide enough for a single person. There it stood: a heavy, dark wooden door with a small brass sign that simply read “Bar.” No name. No fanfare. Just an invitation to a different kind of experience.

If the snack bar was like a living room and the izakaya a kitchen party, this place was a library. Or perhaps a church. The reverence for the drink was tangible. The room was silent except for the soft jazz playing from a vintage sound system, the gentle scrape of a bar spoon against a mixing glass, and the contented sighs of the few other patrons. The bar itself was a single, magnificent slab of polished wood, so smooth it seemed liquid. Behind it stood a bartender in a crisp white shirt and black vest, moving with the quiet confidence of a surgeon. Every motion was precise, economical, and purposeful.

This was a place for connoisseurs. The back bar wasn’t lined with keep bottles, but with a museum-worthy collection of Japanese whiskies, rare gins, and obscure liqueurs. This was a sanctuary for the spirit, both literally and figuratively. I ordered an Old Fashioned, a simple drink with nowhere to hide—a true test of a bartender’s skill. He didn’t just make it; he crafted it. He hand-carved a perfect, crystal-clear sphere of ice, carefully measured the Hibiki whisky, added bitters and a touch of sugar, then stirred. And stirred. And stirred. His focus was hypnotic, chilling the drink to the perfect temperature without over-diluting it. He finished with a twist of orange peel, expressing the oils over the surface before dropping it in. It was a masterpiece—the best Old Fashioned I’ve ever tasted. No exaggeration.

I savored that drink for nearly an hour, soaking in the atmosphere. This was the other side of Takaoka’s nightlife coin: modern in sensibility but ancient in dedication to craft, much like the city itself. Takaoka’s artisans spend decades perfecting the art of casting bronze or shaping lacquerware; this bartender did the same, but his medium was liquid. He was a shokunin—a master craftsman—in his own right. In a world dominated by speed and convenience, a place like this is a rebellion. It is a temple devoted to taking one’s time, appreciating the details, and savoring the moment. It was the perfect nightcap: a quiet, contemplative end to an evening of discovery. It proved that Takaoka’s soul lies not only in its oldest traditions but also in its steadfast commitment to doing things the right way, no matter how long it takes.

The How-To for the Clued-In Traveler

So, you’re sold. You want to explore this hidden world. Bet. But before you start opening random doors, here’s some friendly advice to make your journey smoother. Think of this as your cheat sheet for Takaoka after dark. First off, cash is king. Many of these old-school spots only accept cash. Don’t be that person trying to pay for a 600-yen highball with a credit card—it’s just not the vibe. Stop by a 7-Eleven ATM before you begin your adventure.

Second, don’t fear the otoshi, the mandatory cover charge I mentioned earlier. It usually comes with a small, tasty appetizer. Think of it not as a fee, but as your entry ticket to a private club for the night. The cost is typically a few hundred yen, maybe up to a thousand in some places. It’s part of the culture, so just go with it. Embracing it is part of the experience and shows you’re in the know.

Third, language. Yeah, it can be a challenge. But honestly, it’s less of a barrier than you might think. A big smile and a willingness to be adventurous go a long, long way. Learn a few key phrases: “Sumimasen” (excuse me, to get attention), “Osusume wa nan desu ka?” (what do you recommend?), “Oishii!” (delicious!), and of course, “Arigato gozaimasu” (thank you very much). Your effort, no matter how clumsy, will be greatly appreciated. And get a good translation app on your phone—it’s a game-changer for understanding menus and having those charmingly broken conversations.

Fourth, where to even start? The magic is in the wandering, but a little guidance helps. The areas around Takaoka Station have a good concentration of izakayas. The nearby Suehirocho is the city’s main, though quite compact, entertainment district. But for the real atmospheric gems, you need to explore the side streets off the main roads, especially in and around historic districts like Yamachosuji and Kanayamachi. Look for the lanterns. Follow the delightful aromas. Let your curiosity be your guide.

Finally, and this is the most important tip: be respectful. These aren’t tourist traps; they are local institutions treasured by the community. Be quiet and observant when you first enter. Match the room’s energy. Don’t be loud or obnoxious. Always ask before taking photos of people. Be a good guest. In return, you’ll be met with warmth and hospitality that’s truly unforgettable. You’re not just a customer; you’re a visitor in their space, and that distinction is crucial.

The Last Call for Authenticity

The street grew even quieter now. The last trains had long since left, and the city had settled into a deep sleep. As I walked back to my hotel, the cool night air feeling clean and sharp in my lungs, I reflected on the night. It wasn’t a wild party. There were no epic tales of debauchery. It was something deeper, something more resonant. A night of small connections, quiet moments, genuine human warmth. A glimpse behind the curtain of everyday life in a place many simply pass through.

Takaoka’s nightlife isn’t something you can just find on a top-ten list. It’s not packaged for easy consumption. It’s something you have to earn. You earn it by being curious, by daring enough to slide open that unmarked door, by being open to an experience that might feel confusing or awkward at first. But the reward is great. The reward is a taste of something real, something unpolished for the tourist gaze. It’s a connection to the city’s soul—a soul found not in grand monuments, but in the soft glow of a paper lantern and shared laughter across a wooden bar.

So if you find yourself in this corner of Japan, do yourself a favor and stay the night. See the Great Buddha, by all means. Admire the temples and latticework. But when the sun goes down, put the map away. Take a walk. Follow the light. Slide the door open. The real adventure awaits you in Takaoka’s quiet corners after dark. It’s a whole mood, and it might just be the most memorable one you have anywhere in Japan. Trust me.