Yo, what’s good, world-trekkers! Li Wei here, dropping in with a story that’s literally off the charts and deep underground. Picture this: you’re chilling in Tokyo, vibing with the neon jungle, the scramble crossings, the whole nine yards. It’s an epic scene, for sure. But what if I told you that just a quick bullet train ride away, a whole other universe exists? Not another city, not a serene temple garden, but a colossal, subterranean empire carved by human hands. We’re talking about a place so vast it messes with your sense of scale, so atmospheric it feels like you’ve stepped onto a sci-fi film set. This isn’t some fantasy novel. This is the Oya History Museum in Utsunomiya, Tochigi Prefecture—a former massive underground stone quarry that has been reborn into one of Japan’s most mind-blowing destinations. It’s low-key one of the coolest spots I’ve ever explored, a place where industrial history, modern art, and pure geological wonder collide in the dark. It’s a testament to the sweat and dreams of generations, a cathedral built not by adding stone, but by taking it away. Forget what you think you know about Japan’s tourist spots; we’re going deep on this one. Get ready to have your mind blown and your internal thermostat reset, because where we’re going, the sun don’t shine, but the vibes are immaculate.

If you’re fascinated by Japan’s hidden geological wonders, you might also be captivated by the story of Aogashima, Japan’s mythical lost world.

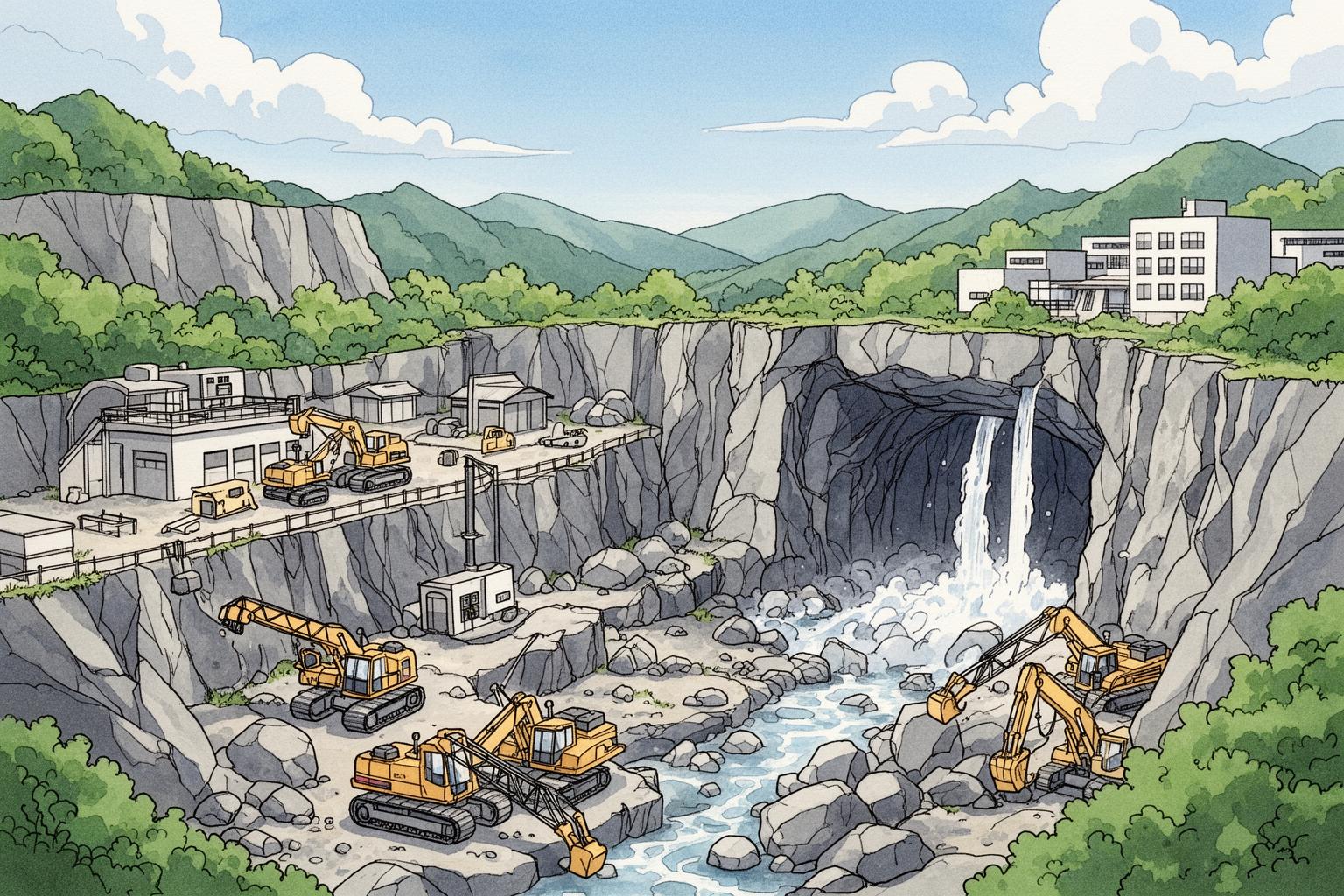

The Vibe Check: What It Actually Feels Like to Descend into Oya

Entering the Oya quarry is a complete sensory reset. The experience begins in a rather unremarkable building on the surface. You pay your ticket, perhaps glance at a few pamphlets, and everything seems quite ordinary. Then, you spot the stairs—a long, steep descent into a vast, dark opening in the earth. The moment you start descending, everything shifts. The first thing you notice is the air. The warm, humid air of a Japanese summer (or the crisp chill of its winter) is immediately replaced by a deep, profound cold. It’s a damp, ancient cold that feels as if it has lingered there for centuries. The temperature steadies at around 8 degrees Celsius (about 46 Fahrenheit) year-round. It’s not merely cold; it’s a presence, a tangible cloak enveloping you. Your breath begins to mist in front of you, and instinctively, you pull your jacket tighter. Forget your weather app; this place exists on its own geological clock.

Then there’s the scent. It’s the aroma of wet stone, minerals, and the Earth’s deep history. It’s pure and primal, completely free from the pollution of the city or the floral notes of the countryside. It’s the smell of stillness and time. As your eyes adjust to the dim lighting, the sheer scale of the space gradually registers, offering a genuinely awe-inspiring moment. The main chamber opens before you like a scene from Lord of the Rings or Dune. It’s a vast underground hall, approximately 20,000 square meters—large enough to hold an entire soccer field. The ceiling towers 30 meters above you, supported by massive, square-cut rock pillars that resemble the legs of forgotten giants. You feel incredibly small, like an ant wandering through a pharaoh’s tomb.

Sound behaves strangely down here. On one hand, the enormous space can absorb noises completely, creating pockets of intense, almost sacred silence. On the other hand, a sudden voice or footstep can echo in eerie, ghostly ways, bouncing off the textured walls. This quiet reverence makes the experience deeply moving. It’s not a natural cave, which feels organic and chaotic. This is a structured, man-made void. The walls bear the marks of their creation—a brutalist mosaic of chisel impressions and saw cuts, telling a story of immense human effort. The modern, artistic lighting is the true highlight of the experience. Without it, the quarry would be a daunting, dark abyss. With it, the space transforms into a living gallery. Deep blues wash over one wall, emphasizing the rough texture. Warm amber hues turn a distant chamber into something like a secret chapel. Shafts of white light pierce the gloom, creating striking silhouettes. It feels less like an industrial ruin and more like a carefully curated installation—a dialogue between raw nature and human craftsmanship. The atmosphere is a unique and beautiful mix: part ancient Egyptian temple, part futuristic alien outpost, and part underground cathedral dedicated to the gods of industry. It’s a place that demands silence and reflection, inviting you to stand still and gaze, completely humbled by its vastness.

A Legacy Carved in Stone: The Unsung Saga of Oya-ishi

To truly experience Oya, you must first understand the stone itself. This entire underground realm exists thanks to a unique geological treasure known as Oya-ishi, or Oya stone. It’s far more than just a rock; it is the central character in this story, a material that has influenced the landscape, economy, and architectural identity of the region for over a thousand years. Its tale is a captivating journey through geology, history, and human ingenuity, linking ancient tombs to one of the most iconic architects of the 20th century.

What Exactly Is Oya Stone?

Let’s dive into geology—but in an engaging way. Oya stone is a greenish-grey, porous volcanic tuff, formed from a massive volcanic eruption millions of years ago. Imagine enormous clouds of ash and pumice settling and compressing over eons to create this distinct, lightweight rock. Its notable qualities made it highly sought after. Firstly, it is relatively soft and easy to carve when freshly quarried, making it ideal for craftsmen. You can see the evidence in the quarry walls, where hand-pick marks remain, a testament to how readily the stone could be shaped. Secondly, it is exceptionally fire-resistant, a valuable property in Japan, where traditional wooden and paper architecture was vulnerable to devastating fires. Constructing a storehouse (kura) with Oya stone was like installing natural fire protection for prized possessions. Lastly, despite appearances, the stone is surprisingly lightweight, facilitating transport and construction. Its porous texture provides a warm, almost soft feel, unlike the cold hardness of granite or marble. It weathers gracefully, developing a patina that enhances its character. Having studied traditional materials across Asia, I find Oya stone to be uniquely Japanese—a fireproof, durable, yet workable material with an aesthetic warmth fitting perfectly with the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi, the beauty found in imperfection and impermanence.

From Ancient Foundations to Imperial Grandeur

The history of Oya stone quarrying is ancient, stretching back to the Kofun Period (circa 250-538 AD), when it was used for stone coffins and burial chambers of powerful clan leaders. Its usage persisted through the ages, becoming a staple material for castle foundations, retaining walls, and paving stones throughout the area. Yet its true heyday was during the Edo Period (1603–1868) when booming commerce drove merchants and affluent farmers to build secure, fireproof storehouses, and Oya stone was the perfect choice. The landscape around Utsunomiya became dotted with these distinctive and sturdy buildings.

However, Oya stone’s international fame and legendary status erupted in the early 20th century thanks to the visionary American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Commissioned to design Tokyo’s new Imperial Hotel—a project of great national significance—Wright sought a material that was both aesthetically distinctive and capable of withstanding Japan’s frequent earthquakes. He discovered Oya stone, enchanted by its texture and ease of carving, using it extensively throughout the hotel for both structural elements and intricate Mayan-inspired decorative motifs. Many contemporaries thought his choice precarious given the stone’s seemingly soft nature. In 1923, as the hotel neared completion, the Great Kanto Earthquake devastated Tokyo, flattening much of the city, sparking fires, and toppling modern buildings. Yet Wright’s Imperial Hotel stood almost untouched. The story instantly became legendary, attributed to its innovative “floating” foundation and the flexible, lightweight properties of Oya stone. Suddenly, Oya-ishi was no longer just a local building material but a global symbol of resilience and architectural brilliance.

The Human Element: The Miners of Oya

This enormous underground network was not carved by machines alone, at least initially. For centuries, it was hewn by hand in a method called tebori. This is where the story becomes truly epic. The miners of Oya were artisans, wielding long-handled picks known as tsuruhashi to painstakingly chip away at the rock face. The work was grueling, back-breaking labor done in near darkness, lit only by the faint glow of oil lamps. They collaborated in teams, cutting massive stone blocks weighing over 100 kilograms, often carrying them to the surface on their backs. The older quarry walls are marked with diagonal hash marks—rhythmic scars left by their picks. Standing there, one can almost hear the ghostly echo of their labor—the repetitive thwack, thwack, thwack of metal striking stone that filled this space for centuries. Each mark serves as a signature, a testament to countless individual efforts repeated millions of times to create this vast cavern.

The industry was transformed in the 1960s with the advent of large stone-cutting machines, marking the start of the kikaibori era. The contrast is immediately visible: some walls show smooth surfaces with clean, straight grooves left by massive saws. The machines accelerated production and enabled the quarry to expand to its staggering current size, but this marked the end of the traditional tebori craft. The quarry’s story physically documents the Industrial Revolution’s impact on manual labor. Eventually, with the rise of cheaper and more versatile concrete after World War II, demand for Oya stone declined. One by one, quarries closed, with this largest site ceasing operations in 1986. It lay dormant, a silent, dark world, until it was reborn as the Oya History Museum—a tribute not just to a unique stone but to the generations of miners whose sweat and hard work carved this wonder from beneath the earth.

Your Epic Quest to the Underground: A Scene-by-Scene Walkthrough

Exploring the Oya History Museum feels like advancing through levels in a video game, with each new chamber unveiling a different aspect of its character. It’s a sensory adventure, so let’s break down the journey you’ll embark on from the moment you leave the sunlight and enter the cool, silent darkness.

The Grand Entrance and the Temperature Shock

As noted, the descent is a rite of passage. The long, straight staircase serves as a gateway between two worlds. With every step downward, you leave behind the noise, weather, and worries of the surface. The temperature drop is so sudden and dramatic that it’s almost amusing, especially on a scorching summer day. You’ll see visitors pause, laugh, and immediately reach for their sweaters. When you finally arrive at the bottom and enter the main exhibition space, the sheer, unfiltered scale of the venue strikes you. This is the moment that floods social media, yet no photo can truly convey the sensation. The ceiling appears impossibly high. The air feels heavy with history. Your eyes struggle to absorb it all—the distant, artfully lit walls, the colossal stone pillars that extend into darkness, the vast emptiness. It’s a profound “whoa” moment that justifies the entire visit within the first ten seconds.

Decoding the Walls: The Art and Scars of Labor

Once your senses adjust, start observing the details, especially the walls. They are a history book etched in stone. In some sections, you’ll notice the rough, almost herringbone pattern of the tebori era. If allowed, run your hand over the surface and feel the texture left by individual pickaxe strikes. These walls possess a raw, organic quality, shaped by muscle, sweat, and a deep understanding of the stone. Moving into other chambers, the walls shift. They become smoother, almost polished in comparison, marked by long, straight vertical or horizontal lines. These are the traces of massive mechanical saws from the kikaibori period. This transition tells a clear and powerful visual story of technological advancement. The quarry itself becomes a museum of its own history. Look closely at the pillars as well—they weren’t carved and placed artificially; they are segments of the original rock intentionally left to support the immense weight of earth above. They serve as the mountain’s bones, carefully preserved to prevent collapse. Everything you see is the result of subtraction—an immense sculpture on a grand scale.

The Illumination Experience: More Than a Quarry, It’s an Art Gallery

What truly transforms the Oya quarry from an industrial relic into a must-visit destination is the lighting. The entire space acts as a canvas for a breathtaking and ever-changing light show. Different areas are lit with colored gels, projectors, and spotlights, turning the cold stone into something warm and vibrant. One chamber may be bathed in a tranquil, deep blue, evoking a submerged Atlantis. Another might feature dramatic, warm spotlights that create the atmosphere of a sacred shrine or magnificent cathedral, which is why it’s a favored wedding venue. Art installations are often scattered throughout the space. You might encounter abstract sculptures that interact with light and shadow, or intricate floral arrangements that contrast the organic with the geological. These exhibits rotate seasonally, so each visit offers a slightly different experience. For photographers, this place is a dream. The low light is challenging, but the striking interplay of light and shadow allows for deeply moody, atmospheric shots. A tip: instead of using a flash that flattens the scene, brace your camera or phone on a railing and try a longer exposure to capture the ambient light. Include a person in your frame to emphasize the monumental scale of the pillars and walls.

A Pop Culture Pilgrimage Site

Beyond the art, Oya has secured its place in modern Japanese culture as a popular filming location. This otherworldly setting is irresistible to directors. Step into the main chamber, and you may feel a sense of déjà vu—and with good reason. This space has been featured in countless music videos by some of Japan’s biggest artists. Legendary rock bands like B’z and X Japan have performed here, their explosive energy contrasting with the quarry’s ancient stillness. Pop idol groups like Keyakizaka46 have showcased intricate choreography in the vast expanse. The list is extensive. It’s also a staple in film and TV, especially in the tokusatsu (special effects) genre, having served as the secret lair for villains in Kamen Rider and Super Sentai many times. The dramatic, shadowy environment is ideal for epic hero-versus-monster battles. It also appeared in the live-action Rurouni Kenshin films, providing a suitably dramatic backdrop for samurai action. For fans of Japanese pop culture, visiting Oya is like a pilgrimage. You can stand in the exact spot where your favorite artist shot a music video or where a legendary hero struck a pose. This adds an extra layer of enjoyment and recognition to the exploration, connecting the site’s deep history with the pulse of modern entertainment.

Beyond the Quarry: Leveling Up Your Utsunomiya Trip

A visit to the Oya History Museum is an unforgettable experience, but it’s merely the start of what this often-overlooked region has in store. The quarry takes center stage, yet the surrounding attractions are equally captivating. To fully enjoy your day trip from Tokyo, you absolutely must explore the nearby area, rich in history, spirituality, and some of Japan’s most celebrated soul food.

The Oya-ji Temple and the Goddess of Mercy

Just a few minutes’ walk from the quarry lies Oya-ji Temple (大谷寺), a true treasure that some hurried visitors sadly miss. This is not your average Japanese temple. The main hall is carved directly into a massive cliff of Oya stone, giving the impression that it organically emerges from the rock itself. This rare style of rock-carved architecture in Japan instantly evokes a deep sense of ancient history. Inside the main hall, you’ll discover its greatest masterpiece: the Oya Kannon. This relief carving of the Senju Kannon (Thousand-Armed Goddess of Mercy) is chiseled straight into the cave wall and is believed to be Japan’s oldest stone-carved Buddha, possibly dating back to the early Heian Period. Weathered by centuries, the carving exudes a mysterious and powerful aura. Standing there in the dim hall, I was reminded of the magnificent Buddhist grottoes I’ve seen in China, such as the Longmen Grottoes near Luoyang or the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang. These sites along the Silk Road represent a monumental tradition of faith expressed through rock carving. Witnessing this tradition here, uniquely rendered in Oya stone, created a profound connection across East Asian cultures. Just outside the temple grounds is another striking sight: the Heiwa Kannon, or Goddess of Peace. This enormous 27-meter-tall statue, carved into a cliff, honors those lost in World War II and prays for global peace. It’s breathtaking to behold, serenely watching over the town. Visiting Oya-ji and the Heiwa Kannon offers a spiritual balance to the industrial history of the quarry, illustrating how the same stone served both commercial and devotional purposes.

Utsunomiya’s Soul Food: It’s All About the Gyoza

After a day spent exploring cool quarries and ancient temples, you’re bound to work up an appetite. In Utsunomiya, hunger means only one thing: gyoza. The city is, without exaggeration, Japan’s gyoza capital. Its passion for these tasty dumplings is legendary. The story goes that soldiers stationed in Manchuria during the war brought back the recipe, which quickly took hold in Utsunomiya. Today, the city boasts hundreds of gyoza restaurants, each with its own secret recipe and devoted fans. And you can’t settle for just one variety. The essential trio of Utsunomiya gyoza includes yaki-gyoza (pan-fried with a crispy bottom and juicy filling), sui-gyoza (boiled, served in a light broth, soft and soothing), and age-gyoza (deep-fried, crunchy, and irresistibly tasty). Fillings typically blend minced pork, cabbage, and chives, though seasoning and wrapper thickness vary by shop. Two of the most famous and accessible eateries near Utsunomiya Station are Utsunomiya Minmin and Masashi. Long lines are common, but the wait adds to the experience. The best way to enjoy it is by going on a gyoza crawl, sampling a plate of each style at different spots. It’s inexpensive, delicious, and the most genuine way to savor the city’s culinary heart.

Not Just Gyoza: Utsunomiya’s Cocktail Scene

Here’s a little insider tip. While gyoza steals the spotlight, Utsunomiya also boasts a lesser-known identity as a “Cocktail Town.” For reasons not entirely clear, the city has produced an unusually large number of bartenders acclaimed both nationally and internationally. The cocktail bar scene here is top-notch, rivaling that of far bigger cities. After your gyoza feast, settling into one of Utsunomiya’s quiet, elegant bars is a superb way to conclude your day. You’ll find everything from classic cocktail lounges to inventive bars experimenting with local ingredients like Tochigi’s renowned strawberries. It’s a delightful and surprising side of the city, revealing that there’s always more to uncover beneath the surface—much like the quarry itself.

The Nitty-Gritty: Your Mission Briefing for Oya

Alright, you’re excited and ready to embark. Let’s dive into the practical details to ensure your underground adventure goes smoothly. Planning is essential, but don’t worry, it’s a fairly straightforward trip from Tokyo.

Access and Transportation Logistics

Getting to the Oya History Museum from Tokyo involves two main steps. First, you need to reach Utsunomiya, the capital of Tochigi Prefecture. The quickest and most comfortable option is to take the Tohoku Shinkansen (bullet train) from Tokyo Station or Ueno Station. The trip takes about 50 minutes, arriving directly at Utsunomiya Station. It’s a bit expensive, so if you’re on a budget and have more time, you can opt for a local train on the JR Utsunomiya Line, which takes around 1 hour and 45 minutes but costs less than half the price of the Shinkansen. Once at Utsunomiya Station, head to the West Exit and look for bus stop number 6. You’ll want to catch a bus heading toward “Oya” or “Tateiwa,” identifiable by the destination name “大谷.” The ride lasts about 30 minutes, depending on traffic. Get off at “Oya Shiryokan Iriguchi” (大谷資料館入口), meaning “Oya History Museum Entrance.” The bus journey offers a scenic view through suburbs and countryside where you can spot buildings featuring Oya stone. Have around 450 yen in cash or a charged IC card (like Suica or Pasmo) ready for the fare. If you’re driving, the museum has a large parking lot and is easily accessible via the Tohoku Expressway.

Timing is Everything: When to Go

One of the best features of the Oya quarry is that it’s an ideal destination year-round. With a stable internal temperature of about 8°C, it provides a refreshing escape from Japan’s hot, humid summers. When it’s 35°C outside, stepping inside feels like pure relief. In winter, the quarry can even feel warmer than the outdoors. The museum is open year-round, generally from 9:30 AM to 4:30 PM, with the last admission at 4:00 PM. Naturally, weekends and national holidays are busiest. For a more peaceful, reflective experience with fewer people in your photos, try visiting on a weekday morning. The space is vast enough that it rarely feels crowded, but fewer visitors definitely enhance the mysterious, otherworldly vibe. Check the museum’s official website occasionally, as they sometimes host special events like evening light shows, concerts, or art exhibitions that can add a unique touch to your visit.

What to Wear and What to Bring

Here’s the most crucial practical advice: bring a warm jacket. I cannot emphasize this enough. Even if it’s mid-August and you’re sweating outside, you will feel cold inside the quarry. A fleece, hoodie, or light down jacket works perfectly. You’ll regret coming in just a t-shirt. The next most important thing is your footwear. Wear comfortable, sturdy, closed-toe shoes with good traction. The quarry floor can be uneven and often damp from condensation, making smooth-soled shoes slippery. Sneakers or walking shoes are ideal. Lastly, don’t forget your camera or smartphone. As mentioned, it’s a photographer’s dream. If you’re serious about photography, a camera with good low-light capabilities will be beneficial. A small tripod might help, but be mindful of other visitors. The museum accepts credit cards for tickets, but it’s wise to carry some cash for the bus fare and smaller purchases at the gift shop or nearby cafes.

Li Wei’s Final Take: More Than Just a Big Hole in the Ground

When you leave the Oya quarry and climb the stairs back into the light and warmth of the surface world, it feels like returning from another planet. Your eyes readjust, your skin warms, and the everyday sounds flood back in. The experience leaves a lasting impression because it’s much more than just a tourist attraction. It’s a journey operating on multiple levels. It’s a dive into the deep geological history of our planet. It’s a powerful, tangible monument to human industry and the immense physical effort that shaped our modern world. It’s an unexpected art gallery, where the earth’s raw canvas is illuminated by light. And it’s a surprising hub of pop culture, a secret stage for modern Japan’s creative energy. The quarry is a ‘negative space’ masterpiece. Its beauty was created not by building up, but by carving away, leaving a void filled with stories, atmosphere, and a profound sense of wonder. It reminds us that some of the most incredible places aren’t the towering skyscrapers or ancient castles we see, but the hidden worlds lying just beneath our feet. So next time you’re in Tokyo, dare to venture a little further. Go north. Go deep. Go explore the silent, epic kingdom of Oya. It’s a trip guaranteed to be solid gold. Peace out.