Yo, what’s up, world travelers! Hiroshi Tanaka here, your local guide to the real Japan, the spots that are low-key the soul of the country. Today, we’re time-traveling. No tricked-out DeLorean, no fancy tech. All you need is a handful of coins and an open mind. We’re diving headfirst into the world of the Dagashiya, Japan’s OG penny candy stores. Forget your sterile, brightly-lit convenience stores for a sec. A Dagashiya is something else entirely. It’s a sensory explosion, a living museum, and a community hub all rolled into one cramped, treasure-filled space. Stepping into one is like walking straight into a Hayao Miyazaki film or a long-lost memory from Japan’s Showa Era. It’s a full-on vibe check for the soul. These spots are more than just stores; they’re portals to a simpler time, a vibrant echo of post-war Japan where a 10-yen coin could buy you a universe of happiness. They represent a culture of small joys, neighborhood connections, and the pure, unadulterated thrill of choosing your own treats. Before we get into the nitty-gritty of the candy and the culture, I want you to get a feel for a neighborhood where this magic is still alive and kicking. Check out this map of the Yanaka area in Tokyo, a place that’s held onto its old-school charm and is a prime hunting ground for these nostalgic gems.

To fully immerse yourself in the nostalgic atmosphere of these areas, consider exploring the deeper cultural layers of Tokyo’s traditional downtown districts.

The Vibe Check: What’s a Dagashiya, For Real?

So, what exactly is a Dagashiya? Literally, it translates to something like “cheap snacks shop,” but that hardly does it justice. It doesn’t capture the spirit of the place. Imagine this: you’re strolling down a quiet residential street, far from the neon lights of Shinjuku or Shibuya. You notice a small shopfront, perhaps with a faded plastic awning and sliding glass doors. The paint might be chipped, and a handwritten sign declares it’s open. As soon as you slide the door open, a small bell jingles, and time seems to… pause. Or rather, rewind about fifty years.

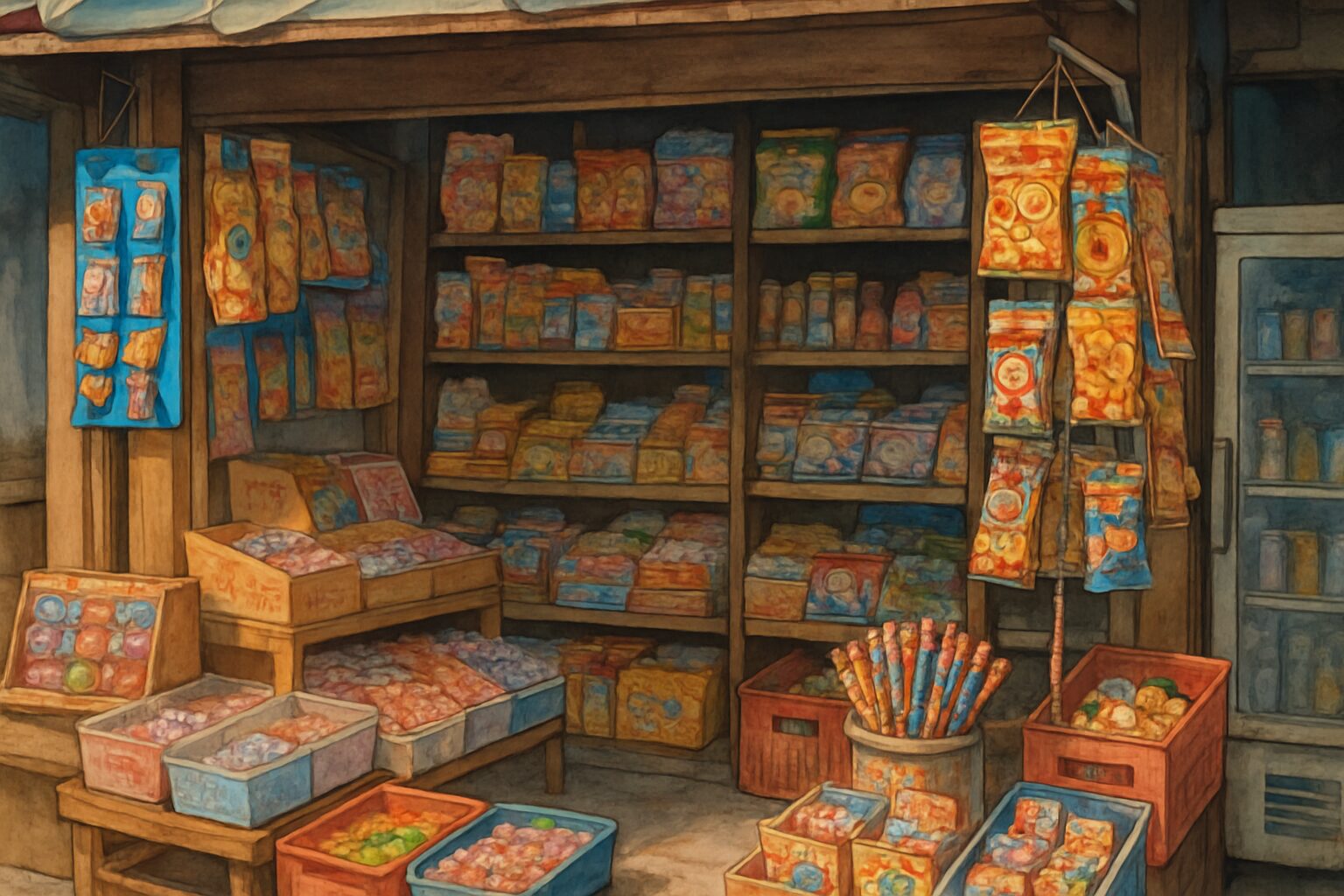

Inside, the air is filled with a distinct scent—a blend of sweet sugar, savory fried crackers, aged wood, and the faint aroma of cardboard boxes. It’s not unpleasant; it’s the smell of childhood. Your eyes take a moment to adjust to the dim lighting, and then you see it: chaos. But a beautiful, organized chaos. Floor-to-ceiling wooden shelves are packed with a vibrant array of colorful packages. Glass jars brimming with gummies and hard candies line the counter. Plastic containers hold mysterious pickled snacks. Strings of squid jerky and puffed rice treats dangle from the ceiling like edible ornaments. The aisles are narrow, barely enough space to walk. Every inch is filled with treasures.

At the center of this small world stands the shopkeeper. More often than not, it’s an elderly woman or man, an obaa-chan (grandma) or ojii-san (grandpa). They’re more than just cashiers; they are guardians of this realm. They might be quietly watching a vintage TV behind the counter or carefully arranging stock. They’ve witnessed generations of children come through the door, clutching sweaty 10-yen coins, their faces etched with intense focus as they make the day’s most important decisions. This person is the living history of the store. They know every product, every price, and probably half the kids’ names in the neighborhood.

Unlike a modern convenience store, a Dagashiya isn’t designed for speed or efficiency. It’s a place to linger. A place to explore. You don’t just grab what you need and leave. You take the small, brightly colored plastic basket—your personal treasure chest—and you browse. You consider your options. Should you pick the chocolate that looks like a cigarette, or the fizzy powder you mix with water? The crunchy ramen bits or the sour plum candy? This choice, made within a tight budget, was a child’s first lesson in economics. A rare moment of autonomy in an adult-controlled world. The sounds are different, too. It’s not the constant electronic beeps and canned greetings of a konbini. It’s the rustle of cellophane wrappers, the clink of coins counted on a small plastic tray, the creak of floorboards, and the muffled sounds of the neighborhood drifting in from outside. It feels handmade, human-sized, and deeply personal. It’s the total opposite of a soulless, corporate retail experience. It’s a vibe. It’s real.

The History Drip: From Post-War Treat to Retro Icon

To truly understand the Dagashiya, you need to know its origins. This entire tradition didn’t emerge overnight. It has deep roots in Japanese history, especially during the Showa Era (1926-1989), which serves as a cultural touchstone for modern Japan’s nostalgic sentiments. The term dagashi itself is ancient, tracing back to the Edo period. At that time, jogashi referred to high-class, refined sweets made with costly white sugar for samurai and aristocrats. In contrast, dagashi were affordable, cheerful treats for the common people, crafted from less refined ingredients like brown sugar or grain syrup. They were the sweets of the everyday folk.

Moving forward to the post-World War II era, Japan was rebuilding its economy, which was beginning to flourish, and a large baby boomer generation was coming of age. This period marked the golden age of the Dagashiya. In the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, these small shops were everywhere—on nearly every street corner in towns across the country. They served as the heart of a child’s world. Consider that this was before video games, the internet, or smartphones existed. A child’s social circle was their neighborhood street, and the Dagashiya was their clubhouse—a dedicated place to hang out after school. Kids would gather their small allowances—where even a 10-yen coin was precious—and flock to the shop. There, they bought snacks, traded manga, chatted about baseball, and simply enjoyed being kids, all under the watchful but generally tolerant eye of the shopkeeper.

The snacks themselves reflected the creativity of that era. Candy makers fiercely competed to win over children’s attention—and their limited coins—which sparked a burst of innovation. Packaging became bright, colorful, and often featured popular anime or manga characters. They created snacks that doubled as toys, such as whistle candies or DIY science kits. A significant part of the charm was the kuji system—a lottery. Many dagashi contained a hidden ticket or tab that, if marked atari (win), rewarded the buyer with a free snack! This element of chance added excitement to the simple act of purchasing a treat, making it thrilling for children.

However, things began to change as Japan grew wealthier in the late 20th century and lifestyles evolved. The rise of supermarkets and especially 24/7 convenience stores (konbini) spelled trouble for many Dagashiya. Konbini were larger, brighter, and stocked a far wider range of products—including sleek, modern snacks from major companies. Children had more money and more entertainment options than before. Meanwhile, declining birth rates meant fewer kids in neighborhoods. Original shop owners aged and retired without successors to continue the business. As a result, thousands of Dagashiya closed their doors, slowly fading into obscurity.

Yet the story didn’t end there. In recent years, there has been a significant revival of interest in Dagashiya. For those who grew up during the Showa era, these shops are powerful nostalgia triggers that instantly bring back memories of childhood. For younger generations and foreign visitors, they symbolize an authenticity that’s hard to find elsewhere—a tangible connection to a romanticized past. This renewed enthusiasm has turned the remaining Dagashiya into treasured cultural landmarks. Some are protected, others recreated in retro theme parks, and many have become popular destinations for tourists seeking an elusive glimpse of ‘old Japan.’ The Dagashiya has evolved from a simple neighborhood candy store into a celebrated icon of cultural heritage.

The Dagashi Lineup: Your Starter Pack for Candy Heaven

Alright, let’s dive into the main attraction: the treats. The vast variety of dagashi can feel overwhelming, but that’s all part of the excitement. They generally fall into a few broad groups—savory, sweet, and just downright quirky. Consider this your guide to the essential dagashi you simply must try. Don’t hesitate to grab whatever looks interesting—that’s the true spirit of the Dagashiya.

Savory Squad – The Umami Hits

Don’t be mistaken; it’s not all sugar here. Some of the most iconic dagashi are salty, savory, and rich in umami. These are the snacks that really stand out.

First up, the undisputed champion: Umaibo. A cultural legend, this cylindrical puffed corn snack translates as “delicious stick,” and it lives up to its name. It’s light, airy, and offers an incredible crunch. But what really sets it apart are the flavors. There are dozens, ranging from classics like Corn Potage, Cheese, and Salami to adventurous choices like Mentaiko (spicy cod roe) and Takoyaki. Each stick is wrapped in colorful foil adorned with its own quirky mascot. At about 10 yen each, collecting and trying every flavor becomes a quest. It’s the perfect introduction to the dagashi world.

Next in line in the savory hall of fame is Baby Star Ramen. Imagine taking a block of instant ramen, crushing it into crunchy bits before cooking, then seasoning it. That’s exactly what this is—a salty, savory, crunchy noodle snack that’s incredibly addictive. You can munch on it straight from the bag, or some even sprinkle it over rice. It’s a brilliant reinvention of a familiar food turned into the perfect bite-sized snack.

Now we step into slightly more… acquired tastes with Kabayaki-san Taro. This is a thin, rectangular sheet made from pressed fish paste, flavored to mimic grilled eel with sweet soy sauce. It has a chewy, almost leathery texture and a strong, pungent fish aroma. Honestly, it’s not for everyone. But for those who grew up with it, it’s pure nostalgia. It perfectly captures the dagashi experience: inexpensive, a little odd, but undeniably memorable.

You can’t discuss savory snacks without mentioning Big Katsu. The packaging suggests a breaded and fried pork cutlet (tonkatsu), a classic Japanese dish. But this is the snack version. Made from fish surimi like Kabayaki-san Taro, it’s coated in breadcrumbs, fried, and slathered with a tangy tonkatsu-style sauce. It’s savory, satisfyingly greasy, and surprisingly fulfilling. The mystery of its exact ingredients adds to its charm.

Sweet Stuff – The Sugar Rush Crew

Naturally, a candy shop must deliver on sweetness, and the Dagashiya certainly does. The sweet selections range from traditional to contemporary, all crafted for maximum pleasure.

A true classic is Fugashi. This is a long, airy stick of dried wheat gluten coated in a crackly layer of brown sugar. The texture is wild—super crunchy on the outside, yet the inside dissolves in your mouth like cotton candy. Simple, rustic, and comforting, it feels like a sweet that’s been beloved for generations—a genuine taste of old Japan.

For a fizzy burst, there’s Ramune Candy. These small tablets of compressed powder candy perfectly capture the flavor of Ramune, the iconic Japanese soda famous for its marble-sealed bottle. The candy fizzes and melts on your tongue, delivering a citrusy, bubbly kick. Often sold in plastic containers shaped like actual Ramune bottles, it adds an extra element of fun.

For a touch of history and beauty, we have Konpeito. These tiny, star-shaped hard sugar candies come in pastel hues and offer a delicate, simple sweetness. Konpeito, introduced by Portuguese traders in the 16th century, is one of Japan’s oldest candies. They even appear in Studio Ghibli’s “Spirited Away,” where soot sprites nibble on them. Holding a handful of these colorful stars feels like holding a piece of history.

And of course, Sakuma Drops deserve mention. These fruit-flavored hard candies come in distinctive metal tins and were immortalized in the poignant Studio Ghibli film “Grave of the Fireflies.” For many, they’re forever linked to that story. The ritual of shaking the tin to hear the candies rattle inside is a cherished memory for generations of Japanese people. Flavors are straightforward—strawberry, lemon, grape, orange—but their cultural significance runs deep.

Weird & Wacky – The Interactive Experience

This is where dagashi truly comes alive. It’s not just about eating; it’s about playing. Many snacks are designed as experiences, mini-games, or toys.

Leading the pack are candies with “fue” in their name, which means whistle. Fue Ramune and Fue Gum are candies with a hole in the center so you can blow through them to produce a high-pitched whistle. They include a tiny toy in the box, making them a double reward. Annoying parents and delighting kids for decades, these are staples of the Dagashiya soundscape.

Then there’s the legendary Neru Neru Nerune. This is a DIY candy chemistry set that comes with a small plastic tray, a spoon, and several packets of mysterious powders. You add water to one powder, and it changes color and foams up into a fluffy, goo-like texture. Next, you add another powder for a different flavor and hue, then dip the goo into crunchy sprinkles. Does it taste amazing? That’s up for debate. But the fun of making it ranks among the best candy experiences. It’s magic and science rolled into one.

From a bygone era come the Cigarette Candies. These candy sticks—sometimes chocolate, sometimes chalky sugar—come in small boxes that perfectly mimic cigarette packs. Kids would pretend to smoke them, imitating the cool adults they saw in movies. Though they’ve grown controversial today, they remain iconic Showa period artifacts and offer a fascinating glimpse into a different time.

Finally, the thrill of chance is embodied in Kuji-tsuki Dagashi, snacks with an attached lottery. These could be anything from gum to gooey mochi on a stick. The packaging has a hidden peel-off section revealing if you’ve won. A red character for atari (win) means you bring the wrapper back to grandma and claim your free prize. A blue character for hazure (lose) means better luck next time. This simple game of chance was a central part of the Dagashiya experience, turning a casual purchase into an exciting moment.

How to Dagashiya: The Unwritten Rules & Pro Tips

Walking into a Dagashiya for the first time can feel like stepping into a secret club. There are no English signs, and the system might not be immediately clear. But don’t worry; the rules are simple, and the atmosphere is very welcoming. Here’s the rundown on how to do it right.

First, grab a basket. Near the entrance, you’ll usually find a stack of small plastic shopping baskets, often in bright primary colors. This is your container. Picking one up signals you’re on a mission. It’s an essential part of the ritual and makes it easier to carry all the little items you’re bound to choose.

Next, set your budget. The real fun in a Dagashiya is seeing how much you can get with a small amount of money. This isn’t the place to flash big bills. The spirit of the game lies in the small coins. A good starting point is giving yourself a 500-yen budget (around $3-4 USD). With that, you can assemble an impressive haul. It pushes you to pay attention to prices—10 yen here, 30 yen there—and make those tough decisions. It’s a fun challenge and a core part of the experience Japanese kids have enjoyed for decades.

Now for the best part: the hunt. Take your time. Wander the narrow aisles. Look up, look down. Some of the coolest things are hidden in plain sight. Don’t just pick what you know. The goal is exploration. Try that strange-looking squid jerky. Grab the pack of sour powder with the wild cartoon character on it. Part of the delight is the mystery. You might find your new favorite snack, or you might end up with something truly bizarre. Either way, you’ll have a story to tell.

Once your basket is full of treasures, it’s time to check out. Bring your haul to the counter where the obaa-chan or ojii-san will be waiting. Here you can witness some old-school magic. They won’t scan barcodes. Instead, they will quickly total your items in their head or, if you’re lucky, on a traditional Japanese abacus called a soroban. It’s an impressive skill to see. Pay with cash, preferably coins. Flashing a 10,000-yen note for a 300-yen purchase is a bit of a faux pas. Small change is king here. When you receive your items, usually in a simple plastic bag, a polite “Arigatou gozaimasu” (Thank you very much) is always appreciated.

For first-timers, here’s a pro tip: try to create a balanced mix. Pick at least one item from each major category. Grab an Umaibo for a savory crunch, some Ramune candy for a sweet treat, a Neru Neru Nerune for a fun, interactive snack, and maybe a Kabayaki-san Taro to challenge your palate. This way, you get the full range of what the Dagashiya world offers. And remember, it’s perfectly fine to eat your snacks right outside the shop. Many Dagashiya have a little bench or stoop that acts as an unofficial tasting area. It all adds to the relaxed, community vibe.

A Pocketful of Memories

A visit to a Dagashiya is far more than just a shopping trip. It’s an immersive journey into the cultural essence of Japan. It offers a tangible link to the Showa Era—a time that shapes much of the nation’s modern identity. These small shops serve as living, breathing time capsules, steadfastly resisting the relentless advance of modernity that has transformed much of Japan’s landscape. They stand as a tribute to the strength of community, evoking a time when your neighborhood was your entire world and the local shopkeeper a trusted guardian.

In an increasingly digital, fast-paced, and impersonal world, the Dagashiya provides a precious antidote. It’s a place of simple, analog pleasures. The excitement of discovering a winning lottery ticket on your gum wrapper. The delight of filling a basket with a dozen different treats for less than the cost of a cup of coffee. The quiet, shared experience of browsing the shelves alongside local children. These small moments are what make travel truly meaningful. The real heart of a culture is found not in grand temples or towering skyscrapers, but in the humble corners where everyday life happens.

So, as you explore the incredible cities and towns of Japan, stay alert. Spot that faded awning, that cluttered window display, that bell jingling on a sliding door. When you find one, don’t hesitate. Step inside. Leave your adult seriousness behind and embrace your inner child. Arm yourself with a few hundred yen and set off on your own personal treasure hunt. You won’t just leave with a bag full of strange and wonderful snacks; you’ll take away a pocketful of memories and a deeper, more authentic understanding of Japan. Honestly, it’s an experience you won’t forget. Go make some stories, one 10-yen coin at a time. It’s going to be lit.