Yo, what’s up world! Ayaka here. Let’s talk about that post-slope feeling. You know the one. Your legs are jelly, your cheeks are flushed from the cold, and every part of you craves warmth, good food, and a vibe that’s just… perfect. In the West, they call it après-ski. But here in Japan, in the deep-snow country of Nagano, we have our own version, and honestly, it’s next-level. Forget the swanky lounges for a sec. I’m talking about something way more legit, more heartwarming. I’m talking about hashigo-zake—izakaya hopping through a village that looks like it’s been plucked straight out of a fairy tale. Picture this: steam billowing from ancient hot springs, narrow cobblestone streets muffled by a thick blanket of fresh powder, and the soft, inviting glow of red paper lanterns swaying in the gentle snowfall. This is Nozawa Onsen, a legendary ski and onsen village that has mastered the art of being cozy. It’s here, hopping from one tiny, wooden-clad pub to another, that you’ll find the true soul of Japanese winter. It’s a journey of flavors, a marathon of moods, and a real-deal connection to the culture. This isn’t just about finding a place to drink; it’s about finding a place to belong, even if just for one unforgettable, snowy night.

To truly understand the magic of Japan’s winter wonderlands, you should also consider exploring the mystical backcountry.

The Vibe Check: Stepping into a Winter Dream

Before you even slide open the first izakaya door, you need to pause and fully absorb the atmosphere of Nozawa Onsen. Seriously, just stand in the middle of O-yu Dori, the main street, and let everything sink in. The air here feels different—crisp, clean, and carrying the faint, slightly sulfuric scent of the natural hot springs bubbling up from beneath the ground. This village hums with the sound of water—the gurgle of streams flowing through channels along the streets to prevent freezing, the hiss of steam escaping from vents. The sight is enchanting. Traditional Japanese ryokans and shops, their dark wooden frames sharply contrasting with the brilliant white snow piled high on their roofs, create a magical scene. At night, everything changes. The world shrinks to warm pools of light cast by lanterns, tinting the falling snowflakes orange as they drift downwards. You’ll hear the crunch of your boots on the packed snow, interrupted by the cheerful clatter of people walking in geta—traditional wooden clogs—heading to one of the thirteen public bathhouses, or soto-yu. Laughter spills from behind foggy windows, a fleeting burst of warmth and sound quickly absorbed by the quiet hush of the snow. It’s a sensory overload in the best way. This feeling of being enveloped in a cozy blanket of history, nature, and community sets the tone for the evening. It’s not just cold; it’s a cold that makes the promise of warmth inside all the more inviting. This is the authentic Japanese winter experience—a world apart from commercialized ski resorts. It’s slow, genuine, and deeply, deeply comforting.

Izakaya 101: More Than Just a Bar, It’s a Mood

So, what exactly is an izakaya? If you’re new to Japan, this is essential to know. The word itself breaks down into ‘i’ (to stay), ‘zaka’ (sake/alcohol), and ‘ya’ (shop)—a “stay-drink-place.” But that simple translation only scratches the surface. An izakaya is like the living room of a Japanese neighborhood. It’s not a restaurant where food takes center stage and drinks play a secondary role. It’s not merely a bar where you go to get drunk. Rather, it’s a balanced ecosystem where food, drink, and conversation hold equal importance. It’s a spot to relax after a long day, reconnect with friends, and share small plates of delicious food alongside a steady stream of drinks. The atmosphere can range from lively and rustic to calm and sophisticated, but the underlying principle remains: comfort and connection. Upon entering, the first thing you’ll probably hear is an enthusiastic “Irasshaimase!” (Welcome!) from the staff—a greeting that immediately makes you feel acknowledged and welcomed. You’ll receive an o-shibori, a hot, damp towel to clean your hands, a small act of hospitality that feels like a warm embrace on a chilly evening. Next comes the otoshi or tsukidashi, a small, mandatory appetizer served with your first drink. Think of it as an edible table charge, often a seasonal bite that sets the tone for the meal. The food menu, or o-shinagaki, is typically an extensive list of small dishes called otsumami, meant for sharing. Here lies the charm—you don’t commit to one large main dish. Instead, you order a few items, gauge how you feel, order a few more, and allow the evening to unfold naturally. It’s a fluid, relaxed dining experience focused on pacing and enjoyment.

The Art of the Crawl: Mastering Hashigo-zake

Now that you’ve caught the izakaya vibe, let’s discuss elevating the experience with hashigo-zake. The term literally translates to “ladder drinking,” meaning moving step-by-step from one establishment to another. This is the Japanese art of the pub crawl, and it’s truly a thing of beauty. However, it’s not about excessive drinking. Instead, it’s a culinary and atmospheric adventure. Each izakaya offers its own specialties, its own master (taisho), its unique crowd, and its distinct soul. Staying in one place all night would be like reading only one chapter of a fantastic book. The aim of hashigo-zake is to sample the local scene’s diversity. You might begin at a bustling, standing-room-only spot for a quick beer and some grilled skewers, then move on to a quieter, more traditional venue to deeply explore the world of sake and enjoy delicate local dishes. The night could end at a tiny, quirky bar run by an eccentric owner, a place that feels like a well-kept secret. The unwritten rule is to have one or two drinks and a few dishes at each stop before moving on. This keeps you moving, refreshes your palate, and lets you experience three or four different atmospheres in one evening. It’s a lively way to explore a town like Nozawa Onsen, allowing your curiosity to lead you from one glowing lantern to the next. It invites you to be adventurous, to peek behind curtains, to slide open doors, and discover the magic inside. It’s a journey, not a destination, with a path paved by delicious food and unforgettable memories.

One Snowy Night: My Nozawa Onsen Izakaya Diary

To truly understand it, you have to experience it firsthand. So let me take you through a detailed account of an ideal izakaya crawl I enjoyed on an absurdly snowy Tuesday night in Nozawa. The kind of evening when massive, fluffy snowflakes fall, making the world feel fresh and new. My face was numb from the cold, my stomach grumbled, and I was eager for the comforting warmth of my first izakaya.

First Stop: Sakai Sakaba – The Energetic Kick-Off

The first stop on any genuine hashigo-zake has to be a lively spot that shakes off the chill and sparks good energy. In Nozawa, that place for me is usually Sakai Sakaba. It’s unpretentious and noisy, which makes it ideal. You can hear it before you see it—a cheerful cacophony of chatter and clinking glasses. The windows are fogged up, a sure sign of a packed, cozy interior. I slid open the wooden door and was met by a wave of warmth and the mouthwatering aroma of grilled chicken and soy sauce. The place was bustling with a mix of locals and international skiers, all still buzzing from their day on the slopes. “Irasshai!” the taisho shouted over the din, a broad smile lighting his face as he expertly turned skewers over a long charcoal grill. No tables were free, but I found a spot at the worn wooden counter, right in the center of the action. Perfect. The first order is always a no-brainer. “Nama biiru, kudasai!” (A draft beer, please!). There’s nothing quite like that first sip of a cold, crisp Asahi Super Dry after a day in the snow. Pure bliss. The otoshi was a small bowl of simmered daikon with miso—simple and comforting. For food, it had to be yakitori. This is their specialty. I pointed to the menu and ordered a few classics: momo (juicy thigh meat), negima (thigh meat and leek), and tsukune (a delightful minced chicken meatball glazed in sweet soy). Watching the taisho work was like theater. His moves were efficient, precise—a dance he’s performed countless times. He salted the skewers with a flick of his wrist, flipped them at just the right moment, and served them piping hot. The chicken was smoky, tender, and insanely good. The energy was contagious. I chatted with an Aussie snowboarder to my left and a local ski patroller to my right. We didn’t discuss anything too serious—just the snow conditions, the best runs, and how amazing the yakitori was. That’s the point. It’s an ice-breaker. After another beer and a plate of crispy karaage (Japanese fried chicken), I felt thoroughly warmed and ready for the next phase. I paid my bill, called out a hearty “Gochisousama deshita!” (Thank you for the meal!), and stepped back into the silent, snowy night.

Second Stop: Kura – A Sake Lover’s Sanctuary

With the buzz from the beer and lively atmosphere at Sakai setting a perfect tone, it was time to slow down and savor. The second stop is for appreciation—to dive deeper into Japanese flavors. I headed to a place called Kura, tucked away in a quiet side alley. The name means ‘storehouse,’ and the feeling is just that—an old, beautifully preserved building with sturdy wooden beams and earthen walls. There’s no loud music—only the soft murmur of conversation and the gentle clinking of ceramic sake cups. It was intimate and respectful. I was welcomed by the okami-san, a graceful older woman in a traditional kimono, who guided me to a seat at the counter. This is a place you come to for sake. The menu wasn’t just a list; it was a curated selection of local Nagano brews and other treasures from around Japan. It can be overwhelming, so I simply asked for a suggestion. “Osusume wa nan desu ka?” (What do you recommend?). The okami-san’s eyes brightened. This was her passion. She asked if I preferred dry (karakuchi) or sweet (amakuchi), light or full-bodied. I chose a local, slightly dry junmai ginjo, served cold (reishu) to best enjoy its delicate, fruity notes. It arrived in a lovely ceramic flask (tokkuri) with a small cup (ochoko). The first sip was clean, complex, and a far cry from the cheap hot sake you might have tried elsewhere. This was artisanal. To complement it, I ordered a plate of basashi—thin slices of raw horse meat, a regional delicacy. It may sound unusual, but it’s incredibly lean and tender, served with grated ginger, garlic, and a sweet soy sauce. A must-try for the adventurous. I also enjoyed pickled nozawana, the leafy green vegetable that gives the village its name. It was salty, crunchy, and the perfect counterpoint to the sake. Here, the pace was gentler. Conversations were quieter. The emphasis was on savoring the flavors. The okami-san explained that my sake came from a small, family-run brewery just over the mountain. It was a story in a glass. This is the essence of Japanese cuisine—seasonality, locality, and craft. After slowly finishing my sake and ordering a small flask of warm sake (atsukan) just to feel the comforting heat spread through me, it was time to move on. I felt calm, centered, and deeply satisfied.

Third Stop: Baron – The Hidden Local Gem

The night was growing late, and the snow fell even heavier. It was time for the third and final izakaya—the wildcard. This is the spot you visit when you’re not quite ready to call it a night, a place you won’t find in any guidebook. It’s the locals’ haunt. In Nozawa, there are a few like this, but tonight I chose Baron. It’s tiny, maybe eight seats squeezed around a counter, run by one gruff yet friendly older man known simply as “Master.” There’s no sign, just a small, dimly lit doorway. You have to know it’s there. I pushed aside the heavy curtain (noren) and was welcomed by a room full of familiar faces—ski instructors, ryokan owners, and longtime residents. Someone shuffled over to make room for me. This was the inner sanctum. The menu? There wasn’t one. The Master simply cooked whatever he felt inspired to make. Tonight, a big pot of nikujaga (savory meat and potato stew) was simmering on a small stove behind the counter. “Nikujaga, hitotsu” (One nikujaga), I said. That was enough. For a drink, the mood here called for something stronger. Shelves were lined with bottles of shochu and Japanese whisky. I ordered a shochu oyuwari—shochu mixed with hot water. A classic winter warmer, simple and soothing. The Master silently poured it, placing the drink and a bowl of stew in front of me. The nikujaga was pure comfort—no frills, just Japanese soul food. The potatoes were tender to the point of falling apart, the beef was soft, and the broth perfectly balanced sweet and savory. It tasted like home. The conversation flowed quickly in Japanese, a local dialect. I caught only bits and pieces, but it didn’t matter. The sentiment was universal. A community sharing stories, laughing, grumbling about tourists, and celebrating their life in this beautiful, secluded village. Here beats the true heart of Nozawa Onsen. I sipped my shochu, listened to the tales, and felt completely content. This is the magic of hashigo-zake—a journey from a lively welcome at a popular spot, through the quiet respect of a sake bar, to the warm intimacy of a hidden local treasure.

The Grand Finale: Shime Ramen – The Perfect Close

After leaving Baron, warmed by shochu and full from companionship, one last essential step remained. In Japan, a night of drinking is often capped with a final dish to ‘close’ the evening, known as shime. The undisputed king of shime is a steaming bowl of ramen. It’s a ritual. I trudged through the now-deep snow to one of the few places still open, a tiny ramen-ya with a light on. Inside, it was just the chef and a few other late-night diners like me. I ordered a classic shoyu ramen. In minutes, a beautiful, aromatic bowl arrived. The soy-based broth was rich and savory, the noodles springy and chewy, the slices of chashu pork melted in my mouth, and the soft-boiled egg (ajitama) had a perfectly jammy yolk. Slurping those hot noodles, feeling the savory broth warm me from within, was the most satisfying culinary experience imaginable. It’s the ultimate comfort food, a culinary full-stop signaling a successful night. It absorbed the alcohol, settled my stomach, and readied me for the cold walk home. It was the perfect, soulful conclusion to an ideal snowy night in Nozawa.

The Pro-Tips: How to Navigate Like a Local

Feeling inspired to embark on your own hashigo-zake adventure? Absolutely! Here are some tips to make your first experience less daunting and much more enjoyable.

First, getting there. Reaching Nozawa Onsen is really simple. From Tokyo, take the Hokuriku Shinkansen (bullet train) to Iiyama Station—it’s under two hours. Right outside Iiyama Station, the Nozawa Onsen Liner bus will be waiting to take you straight to the village in about 25 minutes. It’s super convenient.

As for timing, the best season is definitely winter, from December to March. This is when the snow is deepest and the après-ski atmosphere is at its best. If possible, plan your visit for mid-January. On January 15th each year, the village holds the Dosojin Matsuri, one of Japan’s most incredible and wild fire festivals. It’s a breathtaking display of tradition and community spirit you’ll never forget.

Now, about izakaya etiquette. Don’t hesitate! A glowing red lantern (akachochin) outside signals an izakaya. Just slide the door open and step inside. If you don’t speak Japanese, no worries—a smile and a simple point go a long way. Many places in tourist-friendly Nozawa offer English menus, but if not, just watch what others order and point. Saying “Kore, kudasai” (This one, please) works like magic. A few more key phrases will make you stand out: “Sumimasen!” (Excuse me!) to get the staff’s attention, “Okanjo, onegaishimasu” (Check, please), and always finish with a sincere “Gochisousama deshita!” (Thank you for the delicious meal!) when leaving. It shows great respect. Keep in mind many smaller, traditional spots accept cash only, so make sure to hit the ATM beforehand. Lastly, the golden rule of hashigo-zake: pace yourself. It’s a marathon, not a race. Stick to one or two drinks and a couple of small plates per stop. The aim is to wake up the next morning feeling refreshed and ready for the slopes, not overcome by a hangover.

Beyond the Lanterns: Onsen, Culture, and Connection

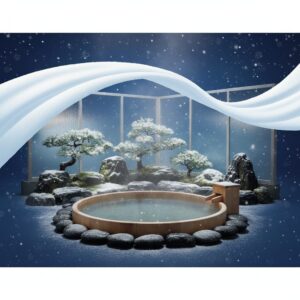

An evening spent hopping between izakayas in Nozawa Onsen is wonderful on its own, but it becomes a truly elevated experience when combined with the village’s other hallmark: its onsen. Scattered throughout the village are 13 public, free-to-use bathhouses known as soto-yu. These are not luxurious spas; rather, they are simple, rustic, and lovingly maintained by the villagers themselves, serving as the community’s heart. Before you even consider your first beer, I strongly recommend a pre-izakaya soak. Choose a soto-yu (O-yu, located in the center, is the most famous and beautiful, but the smaller ones are just as enjoyable) and immerse yourself in the volcanically heated, mineral-rich water. Be warned: the water is HOT. Yet, sinking into that scorching bath after a day of skiing, allowing it to ease your aching muscles, is a sublime experience. It warms you deep to your core. Then, when you step back out into the cold night air, your body radiates warmth, making you almost immune to the chill. Walking to your first izakaya with that post-onsen glow is one of life’s best feelings. Just remember the onsen etiquette: wash thoroughly before entering the bath, and swimsuits are not permitted. It’s all about cleanliness and respect. This ritual—the cycle of skiing, soaking, and socializing—is what makes Nozawa so unique. It connects you to the natural environment, a centuries-old wellness tradition, and the local community that centers around these shared spaces. The izakaya is just one element of this rich cultural tapestry.

A Warm Farewell from the Snowy Village

As you finally return to your ryokan late at night, with a satisfied stomach and a joyful heart, the village is quieter than ever before. The only sounds are the soft hiss of falling snow and the distant murmur of the onsen streams. The footprints you left earlier are already being covered by a fresh blanket of white, erasing the path but not the memories you created. An evening spent hopping between izakayas here is so much more than just a night out. It’s a full cultural immersion. It’s the taste of local Nagano sake, the smoky char of yakitori straight from the grill, the comforting warmth of a homemade stew. But beyond that, it’s the smiles shared over the counter, the laughter exchanged with strangers who become friends for the night, the feeling of being embraced by a close-knit community in a place that feels a world away from home. It’s the ultimate expression of the cozy, communal spirit that defines the Japanese countryside in winter. So when you visit Japan’s snow country, sure, enjoy the incredible powder. But when the lifts cease, and the sun sets behind the mountains, follow the lanterns. Slide open the doors. Take a seat at the counter. The real adventure is just beginning.