There are places in this world where the veil between past and present feels impossibly thin. To step into the Omori district of Iwami Ginzan is to experience this phenomenon firsthand. Here, nestled deep within the verdant, mist-shrouded mountains of Shimane Prefecture, time does not merely stop; it flows differently, guided by the rhythm of a stream that once ran heavy with the aspirations of a silver-fuelled empire. This is not a recreated historical theme park or a sterile museum exhibit. Iwami Ginzan is a living, breathing testament to a chapter of Japanese and, indeed, world history that is as remarkable for its explosive global impact as it is for its gentle, harmonious preservation today. In 2007, UNESCO recognized this entire cultural landscape—the mines, the towns, the transport routes, and the ports—as a World Heritage site, not for the monumental scale of its ruins, but for the exceptional way its industrial past has been integrated with the natural environment and the continuing life of its community. It is a story of ambition, hardship, artistry, and ultimately, a profound respect for nature that offers a unique window into the soul of old Japan. This is a journey into a valley where the whispers of a silver rush still echo, waiting to be heard by those who walk its quiet streets and forested paths.

To further explore the natural wonders of Shimane Prefecture, consider a visit to the Oki Islands Geopark.

A Journey into Japan’s Silver Veins: The Rise of a Global Powerhouse

The story of Iwami Ginzan serves as a powerful reminder that history is often forged in the most unassuming places. Its origins trace back to the early 14th century, but its rise to global prominence began in the 16th century during Japan’s tumultuous Sengoku, or Warring States, period. As powerful feudal lords, or daimyo, competed for dominance, the vast silver deposits discovered here became a coveted prize. The silver from Iwami became the financial backbone for some of the era’s most influential clans, such as the Ouchi and later the Mori, who fiercely battled for control of this immense wealth. The high-quality silver, known as “Soma-gin,” was not just a domestic treasure but also a global currency.

What truly distinguished Iwami Ginzan was the introduction of a revolutionary East Asian smelting technique called the Haifuki-ho method. Invented in the 1530s, this cupellation process enabled the efficient mass production of high-purity silver from ore, a technological breakthrough that elevated the mine’s output from a regional resource to a global economic powerhouse. At its peak in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, under the unified rule of the Tokugawa shogunate, Iwami Ginzan accounted for an astonishing share of the world’s silver production—some historians estimate it to have been as much as a third of all silver in circulation. This flood of precious metal flowed out of Japan through designated ports, fundamentally reshaping global trade. Iwami silver became a crucial commodity in expanding trade with Ming Dynasty China, whose silver-based economy demanded enormous quantities. European traders, especially the Portuguese and Dutch, eagerly sought Japanese silver to acquire silks, spices, and other exotic goods throughout Asia. In an era before global financial markets, the silver hand-extracted from these remote Japanese mountains lubricated international commerce, appearing in European coinage and financing colonial ventures. The name “Argent,” or silver, on old European maps referring to Japan provides direct evidence of Iwami Ginzan’s widespread fame. The shogunate skillfully managed this resource, establishing direct control over the mine and using its profits to strengthen its power, construct castles, and create a stable, unified Japan that enjoyed more than two centuries of peace during the Edo period.

The life of a miner was one of immense hardship. Working in dark, narrow, and dangerous tunnels called ‘mabu,’ they chipped away at the rock face with hand tools, often enduring horrendous conditions. The mine was a complex society itself, housing thousands of miners, officials, merchants, and artisans all living and working in the valley. However, as centuries passed, the most accessible silver veins became depleted. Mining grew increasingly difficult and less profitable. By the Meiji Restoration in the 19th century, Iwami Ginzan was in decline, overshadowed by more modern, industrialized mines. It officially ceased operations in 1923, and its once-thriving towns slipped into a long, quiet slumber. Ironically, this decline became its saving grace. With no economic incentive for modernization, the valley was largely forgotten by the 20th century, inadvertently preserving its Edo-period landscape and the harmonious coexistence between its industrial heritage and the surrounding forest—a quality that later earned it recognition as a world-class heritage site.

The Landscape as a Living Museum: Why Iwami Ginzan is a UNESCO Treasure

The UNESCO inscription for Iwami Ginzan is distinctive. It honors not only the industrial relics but the entire ‘cultural landscape,’ recognizing how the mine’s operations were closely linked with the natural environment. The committee commended the site for demonstrating sustainable land use, where the forest was carefully managed to supply timber for the mineshafts and charcoal for the smelters, before being allowed to regenerate. This comprehensive approach to preservation is what makes the visit so immersive. The heritage site broadly consists of three interconnected components that together tell the complete story of the silver’s journey from mountain to sea.

The Silver Mine and its Mining Towns

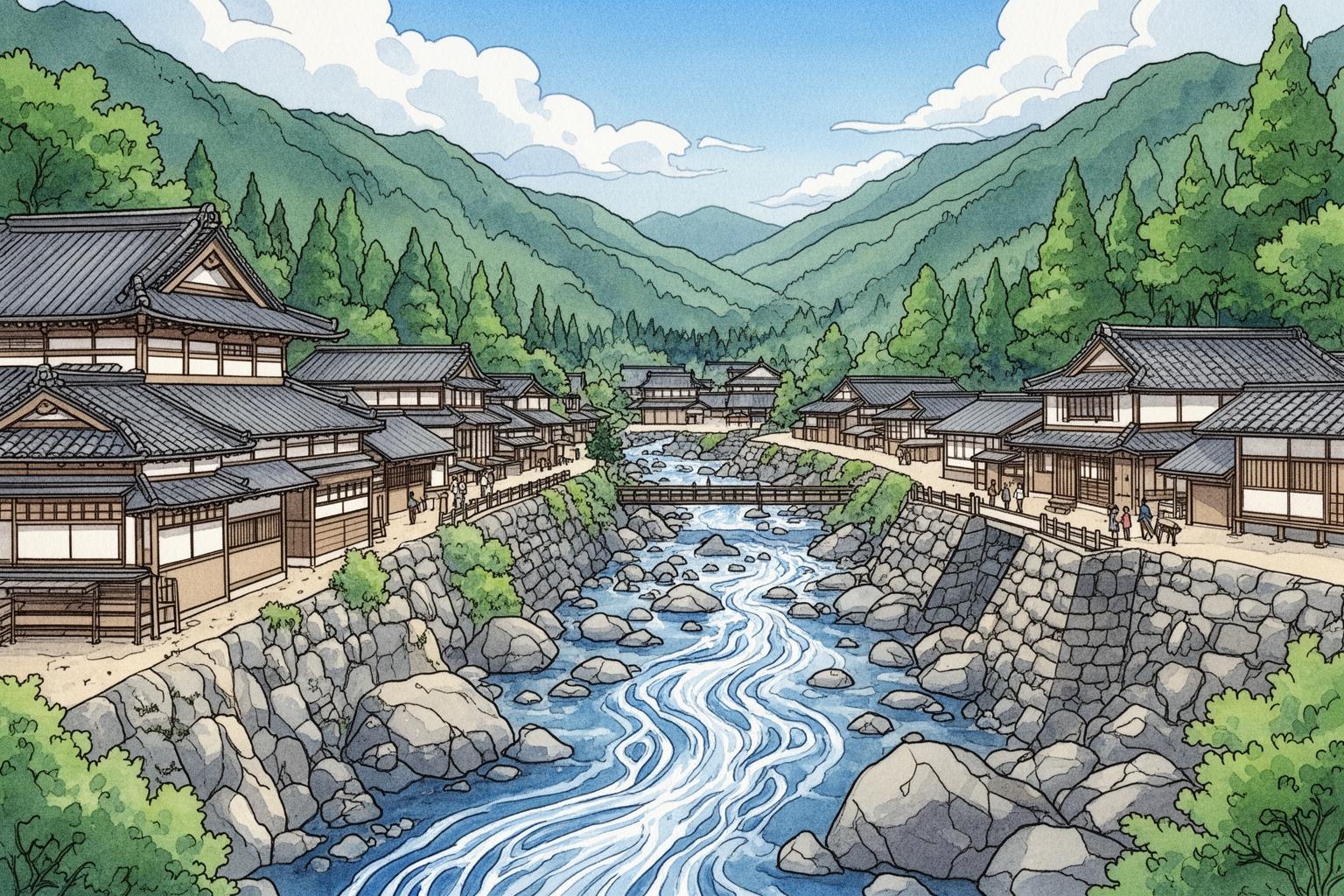

This forms the core of the Iwami Ginzan experience. At its heart lies the beautifully preserved town of Omori. Strolling down its main street, gently winding alongside a clear stream, feels like stepping onto a film set—except it’s entirely real. The town’s exceptional preservation is immediately noticeable. There are no telephone poles or overhead power lines to disrupt the view; they have all been buried underground, reflecting the community’s dedication to authenticity. The street is lined with historic wooden buildings featuring dark latticework and distinctive deep-red ‘Sekishu-gawara’ roof tiles, a local product renowned for its durability in the region’s cold winters.

Many buildings are open to visitors, offering insight into the society supported by the mine. You can explore the former Magistrate’s Office (Bugyosho), which served as the shogunate’s administrative center, and imagine officials managing the vast operations. The homes of prosperous merchant families, such as the Kumagai Family Residence, showcase the wealth brought by the silver trade. This extensive complex, with its various storehouses, main building, and elegant gardens, reflects the refined lifestyle of those who benefited from the mine. Another intriguing stop is the Former Kawashima Residence, a well-preserved samurai house that reveals the everyday life of the warrior class charged with guarding the mine and town. Beyond these public museums, many other buildings remain private homes or have been transformed into inviting cafes, artisan shops, and inns, creating a vibrant, living community.

From Omori, a winding forest path leads into the mountains toward the mine shafts themselves. While hundreds of shafts scatter the mountainside, the Ryugenji Mabu is the main one open to visitors. Renting an electric bicycle in Omori is the most enjoyable way to travel this 2.3-kilometer route through lush greenery. Even before entering the tunnel, the temperature cools. Inside, the air is consistently cool and damp throughout the year. The tunnel is not a uniform, machine-cut corridor; it stands as a testament to human labor. As you walk through the dimly lit passage, you can touch the walls and feel the distinct, rhythmic grooves left by miners’ chisels and picks from over 400 years ago. It is a humbling and evocative experience, connecting you directly to the immense physical effort it took to carve this path deep into the earth in search of silver. The tunnel forms a circuit, and walking through it invites quiet reflection on the human cost behind the wealth this mountain produced.

The Transportation Routes

Extracting the silver was only half the challenge; it then needed to be transported to the coast for shipment. A network of ‘kaidō’, or historic roads, was developed for this purpose. These were not wide, paved highways but rugged mountain paths, parts of which remain today as hiking trails. Walking sections of the old Tomogaurado or Yunotsu-Okidomari-do routes offers a different perspective on the landscape. As you traverse the stone-paved sections and forest trails, you can picture heavily guarded convoys of oxen and horses burdened with silver, making their slow and perilous journey from Omori to the ports. These routes were the veins of the silver empire, and hiking them allows you to experience the same natural beauty that samurai guards and merchants witnessed centuries ago, passing by old shrines and stone markers that once guided their way. It is a wonderful way to appreciate the scale of the operation and the deep link between the mine and the sea.

The Port Towns

The final element of the UNESCO landscape is the ports from which the silver began its global voyage. The most prominent and best-preserved of these is Yunotsu. This charming town has a dual identity that remains today. By day, it was a busy port, its harbor crowded with ships waiting to load precious cargo. Its history as a port is still evident in the architecture clustering around the old harbor. But Yunotsu was, and remains, a renowned ‘onsen’ (hot spring) town. The naturally therapeutic, mineral-rich waters were a welcome relief for weary sailors, merchants, and miners. Today, visitors can continue this tradition at the town’s two public bathhouses. The Yakushiyu is a striking retro-style building with milky, intensely hot water believed to have potent healing properties. The Motoyu, with its simpler, more traditional atmosphere, is another local favorite. Soaking in these historic baths is to participate in a ritual that has endured for centuries. Yunotsu’s narrow, winding streets, historic inns (ryokan), and palpable sense of a place linked to both mountain and sea make it an essential part of any visit to Iwami Ginzan, offering a perfect, relaxing counterbalance to the historical exploration in Omori.

Life in the Silver Valley: Experiencing the Preserved Culture of Omori

What truly elevates a visit to Iwami Ginzan beyond a typical historical tour is the tangible sense of a living culture. The town of Omori is not stuck in the past; it is a community that has carefully balanced its heritage with building a sustainable and fulfilling present. This is a place that cherishes slowness, craftsmanship, and a profound connection to its environment. The choice to bury utility lines was made collectively, motivated by a shared aesthetic vision and a desire to preserve the town’s unique atmosphere. The result is a deep quietness, where the primary sounds are the chirping of birds, the rustling of leaves, and the gentle murmur of the Omori stream.

This spirit of mindful living is perhaps best exemplified by Gungendo, a lifestyle and apparel company headquartered on Omori’s main street. Founded by a couple who relocated to the town and drew inspiration from its heritage, Gungendo has become a symbol of the town’s revival. They renovate old houses for their shops and offices, create products inspired by traditional Japanese aesthetics and natural materials, and promote a philosophy of living rooted in community and seasonal rhythms. Visiting their main store, you’ll discover beautiful, comfortable clothing, homewares, and food products that embody the town’s values. They also operate a café, Abe Hekiu Shoten, housed in the former residence of a wealthy merchant, offering a peaceful place to enjoy coffee and cake while absorbing the historic ambiance. Gungendo’s success illustrates how heritage can inspire contemporary creativity and economic vitality, preventing the town from becoming simply a relic.

The culinary scene in Omori, though modest, is equally committed to local quality. Restaurants and cafés occupy beautifully restored ‘kominka’ (traditional houses), serving dishes prepared with ingredients sourced from the surrounding area. Whether it’s a simple bowl of soba noodles, a set meal featuring local mountain vegetables, or a slice of homemade cake, the food reflects the town’s overall ethos of care. The experience is not about Michelin stars, but honest, flavorful food enjoyed in a setting rich in historical charm.

To truly embrace the magic of Iwami Ginzan, an overnight stay is highly recommended. As day-trippers leave, a special stillness settles over the valley. Staying in one of the restored guesthouses in Omori or a traditional ryokan in Yunotsu allows for a deeper connection. Imagine waking to the morning mist drifting down the mountains, taking a quiet early stroll along the main street when no one else is about, or indulging in a late-night soak in a historic onsen in Yunotsu. It is in these tranquil moments that the soul of the place reveals itself, offering a restorative respite from the pace of modern life.

A Practical Guide for the Intrepid Historian and Curious Traveller

Iwami Ginzan’s remote location is a key part of its charm and preservation, though visiting it does require some advance planning. The journey itself adds to the adventure, leading you through the beautiful, less-traveled landscapes of the San’in region.

Accessing the Silver Valley

To reach Iwami Ginzan, you generally need to use both train and bus. The closest major train stations are Oda-shi and Izumo-shi. From cities like Tokyo or Osaka, the fastest route is to take the Shinkansen (bullet train) to Okayama. From there, transfer to the JR Yakumo Limited Express train, which passes through the stunning Chugoku mountain range to either Izumo-shi or Oda-shi Station. From Oda-shi Station, a local bus runs directly to the Iwami Ginzan World Heritage Center and the Omori bus stop, with the bus ride taking about 30 minutes. It’s important to check the bus timetable ahead of time, as services can be infrequent, particularly on weekdays.

For air travelers, the nearest airports are Izumo Enmusubi Airport (IZO) and Hagi-Iwami Airport (IWJ). Both airports offer bus connections to nearby train stations, from which you can continue your trip to Oda-shi. Renting a car is an excellent choice, giving you the most flexibility to explore both Iwami Ginzan and the wider Shimane region at your own pace. The roads are well-maintained, and driving through the picturesque countryside is enjoyable in itself.

Getting Around the Site

Once you arrive, the heritage site is best explored on foot or by bicycle. The Iwami Ginzan World Heritage Center, located just outside the main town, serves as an ideal starting point where you can pick up maps, watch an introductory video, and get a solid overview of the site’s history and scale. From the center, it’s a short walk or bus ride to the Omori town bus stop, which marks the entrance to the historic district. Omori’s main street is pedestrian-friendly and best enjoyed at a leisurely walking pace. To reach the Ryugenji Mabu mine shaft, located about 2.3 kilometers from the town center, renting a bicycle is highly recommended. Several shops near the Omori bus stop offer rentals, and opting for an electric-assist bike makes the gentle uphill ride easy and enjoyable, allowing you to take in the beautiful forest scenery.

Timing Your Visit

Iwami Ginzan is a stunning destination all year round, but spring (April-May) and autumn (October-November) are especially spectacular. In spring, cherry blossoms adorn the valley, and mild weather makes walking and cycling pleasant. In autumn, the mountains transform with vibrant reds, oranges, and yellows, providing a breathtaking backdrop to the historic town. Summer (June-August) can be hot and humid, though the cool interior of the mine shaft offers a refreshing retreat. Winter (December-February) can be cold with occasional snow, covering the town in a serene white blanket and creating a different kind of beauty, though warm clothing is necessary. To fully appreciate the site, plan for at least one full day, though a two-day visit with an overnight stay in either Omori or Yunotsu is ideal. This allows you to explore Omori and the mine shaft on the first day, and visit the port town of Yunotsu and perhaps hike a historic trail on the second day, all at a relaxed, immersive pace.

Essential Tips for First-Time Visitors

- Wear comfortable walking shoes, as you’ll be navigating stone paths, gravel trails, and potentially hilly terrain.

- Bring enough cash. While larger establishments and hotels may accept cards, many smaller shops, cafes, and bicycle rental places only take cash.

- Plan around public transportation. If you rely on buses, download the schedule or pick one up at the station. They run on a fixed timetable, and missing one could mean a long wait.

- Stay hydrated, especially during warmer months. Although vending machines and cafes are available, it’s wise to carry a water bottle while exploring.

- Respect the local community. Remember that Omori is a living town—be considerate of private residences and keep noise levels down, particularly in the early morning and evening.

Beyond the Silver: Exploring the Mystical Heart of Shimane

A trip to Iwami Ginzan offers an ideal gateway for exploring the wider wonders of Shimane Prefecture, a region rich in Japanese mythology and ancient history. Known as the ‘Land of the Gods,’ Shimane provides an abundance of cultural experiences that perfectly complement a visit to the silver mine.

Just a brief train ride away is the Izumo Taisha Grand Shrine, one of Japan’s oldest and most significant Shinto shrines. Its massive ‘shimenawa’ (sacred rope) hanging above the entrance to the main worship hall is a striking sight. Izumo is dedicated to Okuninushi, the deity of nation-building, agriculture, medicine, and especially relationships or ‘enmusubi.’ It is said that all of Japan’s 8 million gods and goddesses convene here in the tenth month of the lunar calendar for their annual meeting. The shrine’s expansive, serene grounds and ancient, majestic architecture convey a deeply moving spiritual atmosphere, regardless of personal beliefs.

Further along the coast lies Matsue, the graceful ‘City of Water.’ This former castle town rests on the shores of Lake Shinji and is interlaced with a network of canals. Its highlight is Matsue Castle, one of only about a dozen original castles still standing in Japan. The castle’s black-and-white keep provides panoramic views of the city and lake. A delightful way to experience Matsue is aboard a Horikawa Sightseeing Boat tour, which glides along the castle moat and canals, passing beneath low bridges and presenting a unique view of the city’s samurai district and historic homes. Matsue was also the residence of writer Lafcadio Hearn (known in Japan as Koizumi Yakumo), and his former home and memorial museum offer fascinating perspectives on the life of a Westerner enchanted by Meiji-era Japan.

For art enthusiasts, a visit to the Adachi Museum of Art is essential. While its collection of modern Japanese art is outstanding, the museum is best known for its garden. For over twenty years, it has been named the best Japanese garden in the country by the Journal of Japanese Gardening. The garden isn’t intended to be walked through but viewed from inside the museum through large windows, framing a series of living paintings that shift with the seasons. The meticulous perfection of the landscapes—from the white gravel garden to the moss garden and waterfall—exemplifies Japanese aesthetic principles in a stunning manner.

A Final Reflection: The Enduring Legacy of Silver

Iwami Ginzan is much more than a relic of industrial history. It offers a profound lesson in heritage, sustainability, and the quiet strength of a community committed to preserving its unique identity. Here, the immense wealth once spread across the globe has been transformed into a different kind of treasure: one of peace, beauty, and a deep, unbroken connection to history. Walking through the silent, hand-carved tunnels of the mabu, you sense the weight of the labor that built nations. Strolling the impeccably preserved streets of Omori, you experience a rare and beautiful harmony between human settlement and the natural world. Soaking in the healing waters of Yunotsu, you engage in a timeless ritual of restoration. A journey to Iwami Ginzan is a journey into the quiet heart of Japan, a place where the echoes of a silver rush have softened into a whisper, inviting you to listen closely and discover the lasting legacy of this remarkable mountain kingdom.