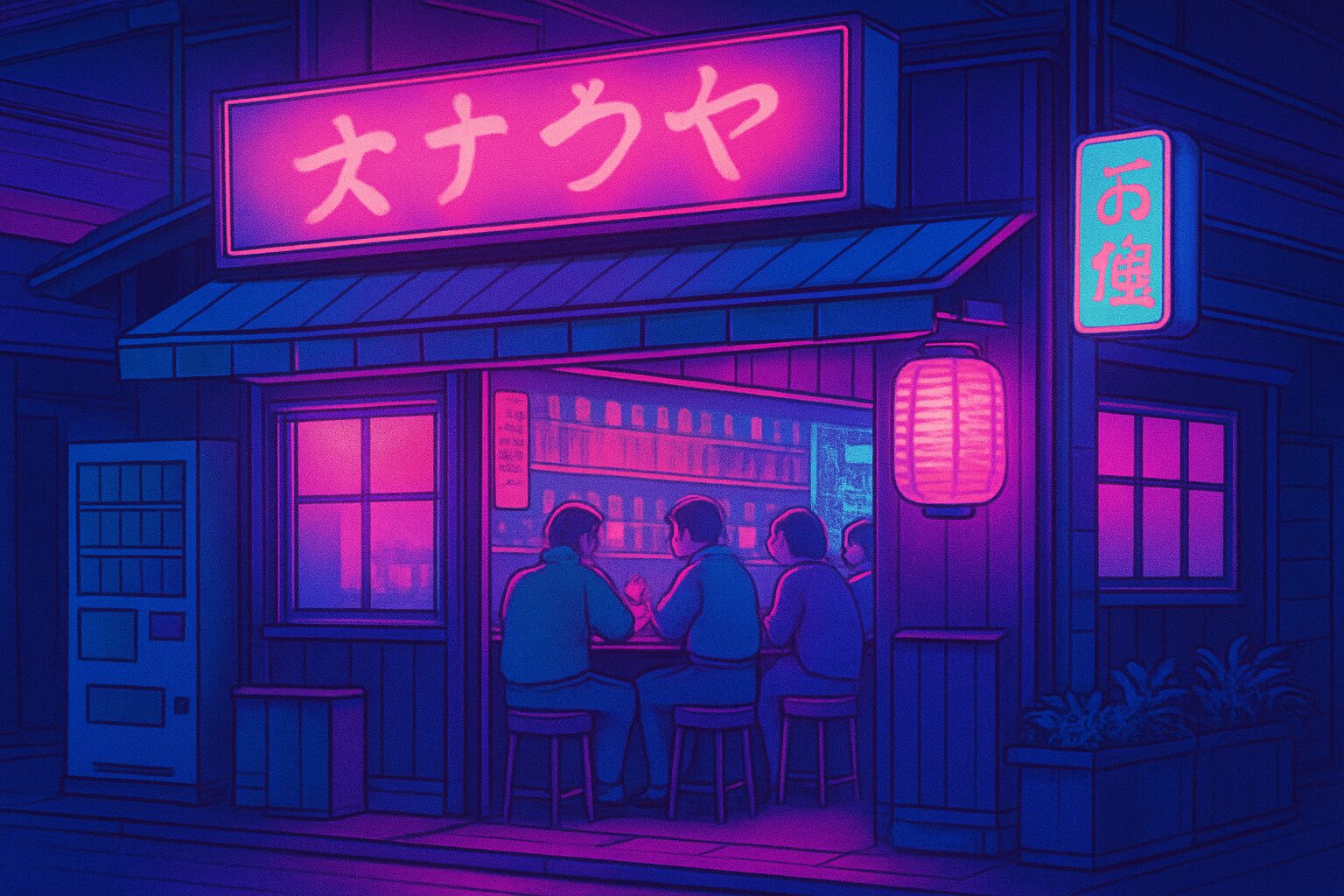

Yo, what’s the deal? If you think you know Japan’s nightlife because you’ve hit a club in Shibuya or an izakaya in Shinjuku, I’m here to tell you, you’ve barely scratched the surface. No cap. The real, unfiltered, and deeply soulful heart of Japanese social life isn’t under strobe lights; it’s hiding in plain sight. It’s tucked away on the second floor of a non-descript building, behind a heavy door with no windows, announced only by a single, humming neon sign. Welcome, fam, to the world of the Showa-era sunakku, or snack bar. This isn’t just a bar; it’s a time machine, a living room, a confessional, and a stage, all rolled into one dimly lit, smoke-hazed, gloriously retro package. We’re talking about a subculture that’s pure vibes, a cornerstone of community that’s been holding it down for decades. Forget your craft cocktails and minimalist decor. We’re about to dive into a world of worn vinyl seats, overflowing ashtrays, soulful karaoke ballads, and the crispest, most legendary highball you’ll ever taste. This is the Japan you don’t see in the guidebooks. It’s an IYKYK situation, and I’m about to give you the keys to the kingdom. This experience is about more than just drinking; it’s about connecting with the ghost of Japan’s electric past, the Showa period, an era of chaotic energy, economic miracles, and boundless optimism that shaped the nation’s modern soul. Getting lost in the labyrinthine alleys where these gems are hidden is part of the adventure. Let’s get this bread.

To fully immerse yourself in this retro aesthetic, you might also appreciate the timeless art of furoshiki wrapping.

The Vibe Check: Decoding the Snack Bar Atmosphere

First things first, let’s get one thing clear: a snack bar isn’t a restaurant. It’s not really a bar in the Western sense, either. Entering one feels like stepping onto a 1975 movie set, where the story is a slow-burning human drama. The air feels dense with history—a potent mix of lingering cigarette smoke from long ago, the faint sweetness of spilled whisky, and the distinct scent of the Mama-san’s daily otoushi, or complimentary snack. For many, this aroma is the smell of coming home. The lighting is always dim, casting long shadows from globe-shaped pendant lamps that hang low over the bar. The color scheme is a blend of dark wood, oxblood red or mustard yellow vinyl, and the warm glow of vintage audio equipment. Every surface tells its own story. The bar top, often a single slab of carefully polished wood, is smoothed exactly where generations of salarymen have rested their elbows after a long day. The shelves behind the bar form a museum of personal memories, packed not only with Suntory and Nikka bottles but also photos of regulars, dusty trophies from local golf tournaments, and kitschy souvenirs from long-ago trips. This is not a place of sleek, impersonal design; it’s a space of curated chaos, an extension of its owner’s personality.

Then there’s the sound. A snack bar is never truly quiet. The baseline is the gentle hum of a vintage refrigerator and the clinking of ice against glass, a sound as meditative as a temple bell. Layered on top is the music—not a Spotify playlist, but usually a collection of old vinyl records, often sentimental enka ballads or Showa-era pop, or the low thrum of the karaoke machine—a hulking, glittering beast sitting in the corner like a silent god, waiting for its moment of worship. When it starts, the atmosphere shifts. A quiet, unassuming accountant might grab the microphone and transform into a rockstar, pouring heart into a ballad while the other patrons clap along with gentle encouragement. It’s this shared, slightly vulnerable moment that turns strangers into temporary family. The space itself is almost always tiny, a deliberate choice rather than a flaw. Some places in areas like Golden Gai barely seat seven or eight people. This enforced intimacy is essential. You can’t hide in a corner; you’re part of the scene, whether you want to be or not. You’re close enough to hear your neighbor’s sigh, share a plate of peanuts, and join the collective conversation that flows throughout the night, guided by the master of ceremonies: the Mama-san.

The Mama-san: More Than a Bartender, She’s the Main Character

You can’t discuss snack bars without mentioning the Mama-san. She is the sun around which this small solar system of regular patrons revolves. Calling her a bartender or owner barely does her justice. She is the heart, soul, and central nervous system of the establishment. The term “Mama-san” itself is a beautiful relic, a mark of respect and affection that recognizes her matriarchal role. In a society that has been, and in many ways still remains, deeply patriarchal, the Mama-san embodies a distinctive form of female entrepreneurship and authority. For decades, these women have carved out their own realms, creating spaces where they reign as undisputed queens.

A typical Mama-san is often a woman of a certain age, her face a map of late nights, hearty laughter, and countless secrets shared across the bar. Her power is quiet but absolute. She remembers your name, your profession, your favorite drink, the song you sang last visit, and the story you told her about your boss. She’s an exceptional conversationalist, a master of kikubari, the Japanese art of anticipating others’ needs and making them feel at ease without having to ask. She knows when to listen patiently, offer wise advice, crack a bawdy joke to lighten the mood, or tactfully steer the conversation away if it becomes too intense. She serves as a therapist, confidante, business advisor, matchmaker, and sometimes a stern yet affectionate mother figure who will tell you when you’ve had enough to drink.

Her background is often as captivating as the bar she manages. Many Mama-sans entered this world in their youth and worked their way up, saving every yen until they could open their own small establishment. They are savvy entrepreneurs who have weathered economic booms and busts, shifting social norms, and the ever-changing whims of their clientele. The bar reflects her own life and tastes. The food, usually a few simple dishes she prepares herself, is comfort food, the kind that her regulars’ own mothers might have made. Think potato salad, stir-fried noodles, or a basic tamagoyaki. However, her true product isn’t the food or drinks; it’s the atmosphere of belonging she fosters. For her regulars, the snack bar is their “third place,” a term coined by sociologist Ray Oldenburg to describe a space outside home and work where community is nurtured. It’s a refuge from the rigid hierarchies and pressures of corporate life, a place where a company president might duet with a junior clerk, their workplace ranks temporarily dissolved by the democracy of the microphone and the warmth of the Mama-san’s smile. Watching a skilled Mama-san manage her bar is like observing a conductor leading an orchestra, drawing out the best in each instrument and creating a harmonious, if sometimes bittersweet, symphony of human connection. She is, without question, a living legend.

It’s Highball O’Clock: The Art of the Perfect Sip

Alright, let’s reveal the secret behind the drink that defines this entire culture: the highball. If you imagine a sad glass of cheap whiskey mixed with flat soda from a dispenser, you need to erase that from your mind immediately. The Japanese highball, especially when served in an authentic snack bar, is a masterpiece. It reflects the Japanese dedication to perfection through simplicity, the same spirit found in a tea ceremony or the crafting of flawless sushi. Though its comeback is a recent trend, the highball’s origins trace back to the Showa era when Suntory Whisky launched huge campaigns to popularize the drink among everyday people. It was clean, refreshing, and easy to enjoy, the ideal companion for long nights of conversation and karaoke.

So what makes it so exceptional? It’s a ritual with four essential elements.

First, the ice. This isn’t cloudy, fast-frozen party ice. We’re talking about crystal-clear, hand-carved ice blocks, frozen slowly to remove impurities and air bubbles. A skilled Mama-san typically starts with a large block and carefully carves it to fit perfectly in the glass. The clarity and density ensure it melts slowly, chilling the drink without watering it down too fast. It’s a subtle show of skill, but it makes all the difference.

Second, the whisky. The classic choice is Suntory Kakubin, the iconic turtle-shell patterned bottle you’ll spot in every Japanese film from the 60s. It’s not a complex, peated single malt meant for neat sipping. It was crafted specifically to be bright, a bit sweet, and perfectly balanced when combined with soda. The Mama-san measures the whisky precisely—no free-pouring here—into the chilled glass.

Third, the glass itself. Almost always a tall, thin-walled glass called an usu-hari, it’s kept in the freezer until frosty cold. The thin glass enhances the tactile experience of the chilled drink and, some aficionados argue, improves both flavor and carbonation.

Fourth, and most importantly, the soda. This is the secret weapon. The soda water is highly carbonated, coming from a special high-pressure tap that delivers fine, sharp, and long-lasting bubbles. The Mama-san tilts the glass and gently pours the soda down the side, careful not to strike the ice directly, which would agitate the carbonation and cause it to fade. The aim is to preserve every single bubble. A gentle stir, once or twice with a long bar spoon, is enough to blend the whisky and soda together. A twist of lemon peel, squeezed over the top to release its essential oils before dropping it in, adds the final touch. The result is transcendent—crisp, effervescent, and dangerously easy to drink. The first sip delivers a shock of cold, bubbly freshness that cleanses the palate and sharpens the senses. It’s the perfect social lubricant, a drink you can savor slowly or enjoy several over a few hours without feeling heavy. It’s not just a drink; it’s a carefully crafted experience, the liquid embodiment of Showa cool.

The Showa Rewind: A History Lesson You’ll Actually Enjoy

To truly understand the snack bar, you have to grasp the Showa Era (1926-1989). It’s more than just a historical period; it’s a foundational myth for modern Japan. This era was intense, marked by the country’s slide into militarism and the devastation of World War II, followed by an extraordinary post-war recovery often dubbed the “Japanese economic miracle.” This era gave rise to the snack bar culture. In the 1950s and 60s, as Japan rebuilt, a new type of worker emerged: the salaryman. These corporate warriors devoted their lives to their companies, enduring grueling hours. Their social and professional lives became deeply intertwined, and after-work drinking with colleagues and clients evolved from a casual activity into a crucial part of career advancement.

This created the need for a new kind of venue. Traditional geisha houses were too formal and expensive, while Western-style bars felt too foreign. Though izakayas were suitable for a meal and a few beers, what these men needed was a place resembling a home away from home—a space to unwind and forge connections. This is where the snack bar came in. Small, intimate, and managed by a maternal figure, it offered a cozy, semi-private environment. The “bottle keep” system, where customers buy a whole bottle of whisky and leave it at the bar for future visits, was a brilliant innovation. It encouraged repeat visits and gave patrons a sense of ownership and belonging. A name tag hanging from a bottle of Suntory Royal became a status symbol, signaling: “I belong here.”

During the economic boom of the 70s and 80s, known as the Bubble Era, snack bar culture flourished. Companies provided generous expense accounts, and nights out in Ginza or Akasaka became legendary. The snack bar was the central stage for corporate bonding rituals—a place where deals were sealed, promotions toasted, and frustrations vented. The karaoke machine, which hit the market in the 1970s, completed the scene. It offered structured entertainment and an outlet for emotional expression in a society that valued stoicism and restraint. Singing a melancholic enka about lost love or hometown longing allowed these men to express feelings often kept hidden. The snack bar became an essential pressure-release valve for the intense demands of Japanese work life. Sitting in a snack bar today is like sitting in the reverberation of that dynamic, ambitious, and often bittersweet era—a living museum to the generation that built modern Japan, one highball at a time.

The Unwritten Rulebook: How to Not Be a Total Noob

Alright, so you’re ready to take the plunge. Bet. But stepping into a snack bar for the first time can feel intimidating. The door is closed, you can’t see inside, and you have no idea what to expect. Here’s the lowdown on the unwritten rules to help you navigate your first visit like a pro.

Understanding the Cover Charge

First things first, almost every snack bar has a cover charge system. Don’t be surprised when you get your bill and find a charge you don’t recognize. This is completely normal. It’s usually a combination of a sekiryō (席料), or seat charge, and an otoushi (お通し), a small complimentary snack. The total can range from ¥500 to a few thousand yen. This isn’t a scam; it’s simply the business model. You’re not just paying for your drink—you’re paying for your seat, the Mama-san’s time and conversation, and the privilege of using the karaoke machine. The otoushi might be anything from a small bowl of edamame or potato salad to something more elaborate that the Mama-san prepared that day. Accept it graciously; it’s part of the welcoming ritual. Some tourist-friendly places might waive the charge, but at authentic local spots, it’s standard practice.

The Art of the Bottle Keep

You’ll notice shelves lined with whisky bottles labeled with customers’ names. This is the botoru kīpu (ボトルキープ), or bottle keep system. It’s more economical for regulars to purchase a whole bottle rather than pay by the glass. The bar stores the bottle for them, and on future visits, they only pay for the seat charge, ice, and mixers. As a first-time visitor, you’re not expected to buy a bottle. Just order a drink by the glass (gurasu de). But seeing rows of tagged bottles says something important: this place has a loyal following, which is always a great sign.

Karaoke Is a Team Sport

At some point, the karaoke machine will beckon you. Even if you think you can’t sing, you should give it a go. Seriously. In a snack bar, karaoke isn’t about talent; it’s about participation. It’s a group activity. Nobody expects you to be a superstar. In fact, being a little off-key is charming. Choose a song everyone knows if you can—The Beatles, Queen, or a classic Disney tune are usually safe bets. When someone else is singing, be a good audience. Clap along, tap your hand on the bar, and when they finish, offer a hearty round of applause. If they belt out a ballad well, a soft “shibui” (tasteful/cool) is a high compliment. Singing together breaks down barriers and is the fastest way to make friends.

Conversation is Key

Don’t just sit silently scrolling on your phone. The main point is to interact. Talk to the Mama-san. Ask about the bar’s history. Compliment the decor. If you know some Japanese, try it out. If not, a smile and some friendly gestures go a long way. The regulars might be curious about you—the foreigner who wandered into their local spot. Be open and approachable. Buy a drink for the person next to you if the conversation is flowing well. This small gesture can open up a whole new world. Remember, you’re not just a customer; you’re a guest in their space. Be respectful, be curious, and be ready to share a bit of yourself. That’s the real currency in the world of the snack bar.

Finding Your Spot: A Quick Guide to Snack Bar Hunting

So where can you find these hidden gems? They are truly scattered throughout Japan, from the shining towers of Tokyo to the quietest rural villages. However, certain areas are renowned for their dense concentration of snack bars.

In Tokyo, Shinjuku Golden Gai is the most well-known. It’s a preserved piece of post-war architecture—a maze of six narrow alleys filled with over 200 tiny bars. It has become quite popular with tourists, so many establishments are now very welcoming to foreigners, offering English menus and signs. It’s a fantastic, if slightly crowded, starting point. For a more traditional salaryman atmosphere, venture to the areas near Shimbashi or Yurakucho stations, where the streets beneath the train tracks house bars that have remained unchanged for fifty years. Shibuya features Nonbei Yokocho (Drunkard’s Alley), a rougher, more chaotic counterpart to Golden Gai right next to the station. For a luxurious, refined experience, the hidden alleyways of Ginza and Akasaka hold exclusive snack bars with steep cover charges and a prestigious clientele.

But don’t restrict yourself to the famous spots. The best snack bar is often the one you stumble upon by chance. Be bold. Explore a side street. Look for signs—often just a simple name in Japanese accompanied by a small illustration of a whisky bottle or a musical note. The most intimidating ones, with no windows and heavy, soundproof doors, are frequently the most genuine. Take a deep breath, slide the door open, and peek inside. If you spot a few empty seats and the Mama-san gives you a welcoming nod, you’ve hit the mark. If it’s full of regulars who all turn to stare, it might be a jōren-san-nomi (regulars only) spot. In that situation, offer a polite bow and step back slowly. It’s all part of the adventure. The reward is discovering a place that feels uniquely yours—a personal find that will become a memorable highlight of your trip.

The Last Call: Why This Fading World Still Slaps

Let’s be honest. The world of the Showa snack bar is slowly fading. The original generation of Mama-sans is retiring, and their children often show little interest in continuing the business. The regular customers are aging. The very corporate culture that gave rise to the snack bar is itself evolving, with younger generations less inclined to join mandatory after-work drinking sessions. Yet, the snack bar still endures. It persists because it provides something increasingly rare in our hyper-connected yet paradoxically lonely modern world: genuine, unpretentious, face-to-face human connection.

For travelers, stepping into a snack bar offers more than a retro-cool experience—it’s an act of cultural archaeology. It’s an opportunity to engage with a side of Japan that is authentic, deeply human, and hidden from the casual tourist’s view. It’s about the stories you’ll hear, the unexpected friendships you’ll forge over a shared song, and the quiet moments of understanding that transcend any language barrier. It’s about savoring the crisp, cold perfection of a highball made with care and precision. So, on your next trip to Japan, when the sun sets, I challenge you to walk past the brightly lit chain restaurants and tourist traps. I challenge you to find that quiet side street, to seek out that humble, glowing sign. Slide open the door. Take a seat at the bar. Order a highball. You’re not just having a drink; you’re sipping on history, and trust me, it’s a vibe you won’t forget.