Yo, what’s good? So you’ve been scrolling, right? You’ve seen the vids from Tokyo. You know the ramen scene, the steaming bowls, the perfect noodle pulls. It’s a vibe. But then you see something else. Something… deconstructed. A pristine, gleaming mound of thick noodles, chilling on their own plate. Next to it, a smaller bowl, not with a clear broth, but with this thick, bubbling, almost menacingly dark liquid that looks more like a gravy or a stew. Someone picks up a fat clump of noodles, dunks it into the thick stuff, and pulls it out, coated and dripping. That’s tsukemen. And if you were in Japan during the 2010s, this wasn’t just a dish. It was a full-blown cultural phenomenon, an obsession that had people lining up for hours, rain or shine. You might be looking at it thinking, “Okay, so it’s just dipping ramen? What’s the big deal? Why did this specific thing blow up?” Bet. That’s the real question. It’s not just about separating noodles and soup. The story of the tsukemen boom is a deep dive into Japan’s changing tastes, its obsession with perfection, and how a humble staff meal got a serious glow-up to become the undisputed king of the noodle world for a solid decade. It’s a story about texture, temperature, and a flavor profile so intense it literally rewired the nation’s palate. This wasn’t a gentle wave; it was a flavor tsunami, and its epicenter was that thick, savory, umami-packed dipping sauce. To get what this craze was all about, you gotta understand the sauce—the heart and soul of the whole operation. Let’s get into it, for real.

This intense flavor profile perfectly sets the stage for the ultimate late-night ritual, the shime no ramen.

The Birth of a Legend: Tsukemen’s Humble Beginnings

Before the hype, the insane lines, and the god-tier reputation, tsukemen was quietly just a clever kitchen shortcut. No exaggeration. To grasp the 2010s boom, we have to go back all the way to 1955. The story begins with one man, Kazuo Yamagishi, a ramen legend often dubbed the “God of Ramen.” He worked at a place in Nakano, Tokyo, called Taishoken. Kitchen life is hectic, right? Staff often don’t have time for a proper sit-down meal. So, Yamagishi and his team would take leftover noodles, rinse them, and dip them into a bowl of concentrated soup seasoned with soy sauce and vinegar. It was quick, easy, and satisfying. The noodles were served on a bamboo strainer, a zaru, so they called this staff meal mori soba (piled soba), even though the noodles were Chinese-style ramen noodles, not soba. A regular customer noticed them eating this and said, “Yo, I want what you’re having.” After some hesitation, Yamagishi served it. People loved it. When Yamagishi opened his own legendary shop, Higashi-Ikebukuro Taishoken, in 1961, he added this “special mori soba” to the menu. This was the original tsukemen. But here’s the key point: this original version was very different from the thick, gravy-like style that came to define the 2010s. The Taishoken broth was much lighter. It was a clear, shoyu-based soup, tangy from vinegar, slightly sweet, with a hint of chili. It was refreshing, almost like a cold noodle dish for summer, but served all year round. The noodles were thinner, and the whole experience was balanced and subtle. For decades, tsukemen remained exactly that—a beloved but niche dish. It had its hardcore fans, especially around Taishoken and its followers, but it wasn’t a national sensation. It was one among many styles in the vast world of Japanese noodles, respected but not revolutionary. It was viewed as a variation, a side quest in the main ramen story. The idea of separating noodles and soup wasn’t new, either; soba and udon have done it for centuries with dishes like zaru soba. But applying it to ramen noodles with hot broth was Yamagishi’s unique innovation. Yet, it quietly simmered in the background for nearly 50 years. It was waiting for its moment, waiting for a generation of chefs to take Yamagishi’s core concept and turn up the intensity, transforming it from a simple staff meal into a groundbreaking culinary experience.

The Game Changer: Enter the “Gravy”

So, if tsukemen had been quietly simmering in the background for fifty years, what transformed in the mid-2000s to completely change the game and ignite the frenzy of the 2010s? In one word: intensity. A new generation of chefs, raised on the legend of Yamagishi, decided to take his creation and push it beyond all limits. They weren’t satisfied with a balanced, tangy broth. They wanted something that would hit you like a ton of bricks—in the best way. They aimed for a broth so thick, so rich, and so flavor-packed that it clung to every single noodle strand. They created a monster known as Noukou Gyokai Tonkotsu. This style defined the boom. Though it translates to “Rich Seafood and Pork Bone,” that barely scratches the surface. It was no longer just soup. It was a sauce. A flavor explosion. The debut of this style in the early 2000s at shops like Ganja in Kawagoe—and later skyrocketed to fame by Rokurinsha in Tokyo—was the spark. This signaled a paradigm shift. The new mantra was simple: more is more. More pork bones boiled longer. More dried fish milled into powder. More fat, more collagen, more umami. The broth turned viscous, emulsified, and opaque. It was an overwhelming sensory onslaught. And Japan, it seemed, was ready for it. This new-school tsukemen didn’t whisper—it yelled. It demanded your full attention and paved the way for a decade of noodle dominance.

Breaking Down the “Noukou Gyokai Tonkotsu” Essence

To understand why this style was a game-changer, you need to dissect its two core elements. It’s a “double soup” (daburu suupu), a technique where two separately prepared broths are blended at the end to create a layered flavor profile. Here, it was a union of land and sea—a perfect storm of savory richness. The tonkotsu part delivers body, depth, and richness. We’re talking pork bones—femurs, knuckles, spines—boiled vigorously for hours, sometimes even days. This isn’t about crafting a clear, delicate stock like a French consommé. Far from it. The intense heat and constant agitation break down collagen, marrow, and fat, emulsifying them into the water. The result? A creamy, milky-white, incredibly rich base with deep, primal pork flavor and a gelatinous, lip-coating texture. It’s the soul-warming, comfort part of the equation, providing koku—a Japanese term meaning richness, fullness, and lingering mouthfeel. But tonkotsu was just the base. The real knockout, the defining punch that made this style so bold and aggressive, was the gyokai. This wasn’t a subtle fish dashi; it was the whole ocean, intensified and weaponized. The magic ingredient was gyofun, or fish powder. Chefs would grind huge quantities of dried fish—usually sababushi (dried mackerel flakes), niboshi (dried sardines), and katsuobushi (dried bonito flakes)—into a coarse powder. This powder was added liberally to the broth, creating a smoky, pungent, intensely savory fish flavor. It was salty, slightly bitter, and bursting with a sharp, assertive umami. Combining the creamy tonkotsu base with the smoky gyokai hit created magic: the pork fat softened the fierce fishiness while the fish powder cut through the richness. Together, they formed a broth thick like potage, with a slight graininess from the fish powder. It was savory, sweet, smoky, and funky all at once—a flavor profile Japan had never experienced at such intensity. It was addictive. It was over the top. And it was exactly what people craved.

The Noodle’s Evolution: More Than Just a Carrier

With a sauce this potent, the original thin, delicate ramen noodles wouldn’t stand a chance. They’d vanish, be overpowered, or fall apart in the thick, heavy broth. The noodles needed a serious makeover—they had to become protagonists, not facilitators. This led to the rise of thick, chewy, artisanal noodles, crafted specifically for tsukemen. Enter gokubuto-men, or extra-thick noodles. These weren’t your usual instant ramen; they were thick, squared, and robust, commanding attention on the plate. Made from high-protein bread flour, they boasted superior structure and a satisfying wheaty flavor. The feature both chefs and eaters obsessed over was koshi, a Japanese term with no exact English equivalent, describing the ideal noodle texture: firm, springy, with a toothsome chew that offers resistance but isn’t tough. It’s the noodle world’s al dente, but bouncier. Achieving this perfect texture required a crucial step called shimeru. After boiling, the noodles are plunged immediately into ice-cold water. This does two things: first, it halts cooking instantly, preventing sogginess. Second—and more importantly—the cold shock tightens the gluten network, greatly enhancing firmness and chewiness—that coveted koshi. It also rinses off excess surface starch, leaving a clean, smooth texture. The result is a noodle that’s a textural joy on its own. Served cold or at room temperature, these shiny noodles form a fantastic contrast to the piping hot, intense dipping sauce. The experience becomes a play of temperatures and textures: cold, smooth, chewy noodle meets hot, thick, slightly grainy sauce. This interplay was a huge part of the appeal. You weren’t just tasting tsukemen—you were experiencing it. The noodles had become true partners to the broth, a forceful vehicle capable of carrying that rich liquid gold from bowl to mouth without getting lost in the flavor explosion.

The “Why”: Decoding the Tsukemen Craze of the 2010s

Alright, the dish underwent a dramatic transformation in both flavor and texture. But that alone doesn’t fully explain why it sparked such a huge social phenomenon. Why were people willing to wait in line for two, three, even four hours just for a bowl of dipping noodles? The answer lies not only in the bowl itself but also in the cultural context of the time. The tsukemen craze of the 2010s was the perfect convergence of shifting culinary preferences, the rise of social media food culture, and a uniquely Japanese style of competitive hype.

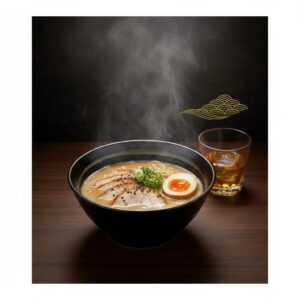

The Sensation Economy: A Dish Made for the ‘Gram

Consider the visuals. Tsukemen is naturally photogenic. It exudes main character energy. Unlike a bowl of ramen where the best ingredients are mostly hidden beneath the soup’s surface, tsukemen presents everything upfront. There’s the neatly arranged, glistening pile of noodles, often fanned out elegantly on the plate. The rich, dark, bubbling broth sits separately in a rustic stone bowl. The toppings—a perfect slice of fatty chashu pork, a vivid orange-yolked ajitama (marinated egg), thick bamboo shoots (menma)—are placed like precious gems. The clean, striking composition practically demands to be photographed. This coincided with the widespread adoption of smartphones and social media platforms like Instagram. Tsukemen was an ideal dish for the emerging era of “food porn.” The interactive nature of the meal—the dipping, pulling, and coating of noodles—was highly visual and shareable. It was an active eating experience, where you crafted your own perfect bite every time. This combination of visual appeal and interactivity made sharing your tsukemen adventure online a form of social currency. Visiting a renowned tsukemen shop wasn’t just about eating lunch; it was about engaging in a cultural event and, importantly, documenting it. The long queue itself became part of the narrative, a symbol of the dish’s worth. A photo capturing the shop’s sign alongside the massive line was as significant as the food photo itself. It was a brag. For those in the know (IYKYK), it signaled insider status—that you had overcome the wait and were about to reap the reward.

A Shift in Flavor Preferences: Japan’s Appetite for Intensity

Cultural context matters too. For a long time, traditional Japanese cuisine, or washoku, was characterized by subtlety, balance, and delicate flavors (assari). However, from the late 20th century and accelerating into the 2000s, there was a marked shift in the national palate, especially among younger generations, toward richer, bolder, and more impactful flavors (kotteri). This was evident in the popularity of heavy tonkotsu ramen, robust miso ramen, and fiery spicy dishes. The noukou gyokai tonkotsu tsukemen was a natural, perhaps ultimate, expression of this trend—a case of flavor maximalism. It delivered an immediate and undeniable hit of umami, fat, and salt. Some experts link this craving for intense, comforting, high-calorie food to the socio-economic conditions. Japan’s “Lost Decades,” following the economic bubble burst in the early 90s, fostered feelings of stagnation and anxiety. During uncertain times, people often seek affordable indulgences and guaranteed satisfaction. A 1,000-yen bowl of intensely flavorful tsukemen offered a powerful, visceral, comforting experience that consistently lifted spirits. It was a form of escape. A reliable win in an unpredictable world. The bold flavor profile required no deep reflection; it was pure, hedonistic enjoyment. This dish met the moment, fulfilling a collective, unspoken desire for something potent and genuine.

The “Tournament” Culture and Media Frenzy

It’s impossible to discuss a noodle boom in Japan without addressing the media environment that sustained it. Long before social media influencers, Japan had a vibrant culture of ramen magazines, televised noodle competitions, and dedicated food websites. These outlets turned eating into a competitive sport. Shops were ranked, reviewed, and matched against one another. Chefs became celebrities. This media hype machine embraced the new wave of tsukemen and amplified its popularity. TV programs aired marathon specials hunting for the best tsukemen in Tokyo. Magazines published detailed infographics on broth ingredients and noodle-making techniques. Early foodie sites like Ramen DB enabled users to rate and review thousands of shops, creating leaderboards that both chefs and customers took seriously. This spurred a culinary arms race. Shops pushed to develop thicker, richer, more intensely flavored broths. The concentration of the dipping sauce, measured in Brix units similar to fine wine, emerged as a key point of pride and marketing. The higher the Brix, the thicker and more concentrated the soup. This media-fueled competition, combined with word-of-mouth, created a feedback loop. A shop featured on TV would attract a massive line the next day; social media chatter about the queue would generate more media coverage. The line itself became proof of quality. In Japanese society, lining up is often seen not as a hassle but as a communal endorsement of a place’s value. Joining the queue signaled membership in an informed group who knew what truly mattered. Surviving the wait was a badge of honor, and the tsukemen at the end was the trophy.

The Tsukemen Ritual: It’s a Whole Vibe, No Cap

Eating tsukemen, especially at one of the legendary shops, is more than just having a meal; it’s a ritual with its own unique set of rules and procedures. For a first-timer, it might feel a little intimidating, but once you grasp the flow, you realize it’s all part of a highly efficient system designed to maximize flavor enjoyment. It’s a performance composed of several distinct acts.

The Ticket Machine Tango

Your experience typically begins not with a waiter, but with a machine: the kenbaiki, or ticket vending machine. This is classic Japan. Instead of ordering from a person, you insert your cash into a button-covered machine, each button representing a different dish or topping. You make your choice, and it dispenses a small ticket. You then give this ticket to the staff (or simply place it on the counter when you sit down). This system is incredibly efficient, streamlining the ordering process, removing payment handling from the chefs, and allowing the small kitchen team to focus solely on cooking. For tourists, it can be a confusing puzzle of Japanese characters, but most popular spots now feature pictures or even English translations. Pro tip: decide what you want while waiting in line outside. Once you’re at the machine, it’s go-time. Press the button for the standard tsukemen, maybe add an ajitama (always add the egg), grab your ticket, and you’ve completed the first step of the ritual.

The Art of the Dip

Once you’re seated and the food arrives, the main event begins. You have your noodles and your soup—now what? The key is restraint. This isn’t like spaghetti, where you drown the noodles in sauce. You’re meant to dip. Pick up a small clump of noodles with your chopsticks—just a few strands. Dip about half to two-thirds of their length into the thick, hot broth. Don’t fully submerge them. You want a gradient of flavor and temperature. Lift them out, let any excess drip briefly, then bring them directly to your mouth. And this is important: slurp. Slurp them loudly and proudly. While this might seem rude in Western culture, in Japan, it is essential to enjoying the noodles. Slurping serves two purposes: it cools down the hot noodles slightly to prevent burning your mouth, and it aerates the noodles and broth, which experts say enhances flavor and aroma. By not dunking the entire noodle, you can appreciate the pure, wheaty taste and chewy texture of the noodle on one end, balanced by the intense, clinging sauce on the other. It’s a perfect, balanced bite every time. Repeat this process, relishing the interplay of textures and temperatures.

Mid-Game Changers: Toppings and Condiments

Your toppings act as the supporting cast, providing contrast and preventing flavor fatigue from the rich sauce. The chashu pork, often served alongside the noodles, can be eaten on its own or dipped briefly. The cool, crisp bamboo shoots (menma) offer a refreshing textural break. The marinated egg, or ajitama, is the true treasure. Eat it in two halves, letting the creamy, jammy yolk mix slightly with the soup for an added layer of richness. Most tsukemen counters also offer a selection of condiments. A common one is vinegar. A small splash added to the dipping sauce mid-meal can cut through the richness, brighten the flavors, and cleanse your palate, helping you reengage with the dish’s intensity. Some places provide chili powder (ichimi) or a seven-spice blend (shichimi) for a bit of heat. Using these is part of personalizing the experience and making it through what can be a very heavy meal.

The Grand Finale: “Soup-Wari,” Please!

This is the final, and perhaps most beautiful, part of the ritual. After finishing all your noodles, you’re left with a small amount of that intensely potent, thick dipping sauce. It’s far too salty and concentrated to drink on its own—but you can’t just leave it; that would waste all the flavor and effort that went into it. This is where soup-wari comes in. You take your bowl to the counter and say, “Soup-wari, onegaishimasu” (Soup-wari, please). The chef will take your bowl and add a splash of hot, light dashi (usually a simple fish- or seaweed-based broth) from a pot reserved for this purpose. They might also add some chopped yuzu peel or green onions before handing the bowl back to you. The dashi dilutes the intense sauce, transforming it from a thick gravy into a perfectly seasoned, sippable soup. This final act is deeply rooted in the Japanese concept of mottainai, a feeling of regret over wastefulness. It’s about using everything and appreciating the chef’s full creation. The soup-wari is a warm, comforting epilogue to your intense flavor journey. It cleanses the palate, settles the stomach, and provides a deeply satisfying conclusion to the meal, leaving you with the complete essence of the broth in a much gentler form.

Beyond the Boom: Tsukemen in the 2020s

The intense white-hot surge of the noukou gyokai tonkotsu boom couldn’t last indefinitely. By the late 2010s, a certain degree of flavor fatigue had set in. The culinary race to achieve maximum thickness and intensity had reached its natural endpoint, with some broths becoming so dense they were nearly solid. The scene was ripe for change. Yet the craze didn’t disappear; it transformed. The boom had firmly cemented tsukemen as a major category in Japanese noodle cuisine, placing it on par with ramen. It had become a lasting fixture. What followed was diversification. Chefs who excelled in the ultra-rich style began exploring new directions, while a backlash against the heaviness sparked a renewed appreciation for subtler flavors. The 2020s have seen an explosion of creativity in the tsukemen world. The noukou gyokai tonkotsu style is now regarded as a “classic” of the boom era, but it’s no longer the only option. New styles have surfaced, each with its own devoted fans. There is a major trend toward niboshi tsukemen, which uses large quantities of dried baby sardines to create a broth less focused on richness and more on a sharp, bitter, and intensely fragrant fishiness. It’s a challenging yet deeply rewarding flavor for enthusiasts. Creamy chicken-based tori paitan tsukemen has also gained immense popularity, providing a rich, savory experience without the heavy pork and strong fish notes of the traditional style. It’s smoother, more refined, and often paired with thinner, flatter noodles. Beyond that, the tsukemen landscape has become a playground for experimentation. You can find high-end tsukemen crafted with sea bream or shrimp, rich Italian-inspired tomato tsukemen topped with cheese, and spicy curry tsukemen that perfectly balances bold flavors. There are even vegan varieties made with rich vegetable and mushroom broths that are surprisingly delicious. The legacy of the 2010s boom wasn’t just a single flavor profile; it was the elevation of tsukemen as a whole. It challenged noodle makers, broth masters, and diners alike to take the dish seriously. It built a foundation and shared language that now foster incredible innovation and diversity. Though the craze has cooled, the flame it sparked still burns brightly, pushing the boundaries of what dipping noodles can become.

Is It Worth the Hype? A Real Talk

So, after all that, we find ourselves back at the original question. You see the lines, you hear the stories. Is it really worth it? The honest answer is: it depends on what you’re after. Let’s be real, no sugarcoating. The classic, boom-era noukou gyokai tonkotsu tsukemen is an intense flavor experience. It’s powerfully porky, powerfully fishy, and deeply rich. For some, especially those unaccustomed to the bold flavors of dried mackerel and sardine powder, the strong fishiness can be overpowering. It’s not a subtle dish; it’s a sledgehammer of umami. If you expect a light, delicate noodle soup, you’ll be taken aback. But with the right mindset, it can be eye-opening. You’re not just eating a meal; you’re tasting a moment frozen in time. You’re experiencing the dish that defined an era of Japanese food culture. It’s a culinary snapshot of a nation’s obsession. Trying it is about understanding why millions fell in love with this intense, challenging, and ultimately rewarding bowl. My advice? Don’t start with the most extreme version you can find. Instead, seek out a well-regarded shop known for its balance. But to truly grasp the craze, you have to try the genuine article at least once. Visit a famed spot. Brave the line. Treat it like a cultural pilgrimage. Order the classic, add the egg, and finish with the soup-wari. You might love it or hate it, but you will definitely understand it. You’ll see why this wasn’t just “dipping ramen.” It was a revolution in a bowl, a radical reimagining of texture, temperature, and taste. It’s the story of how a humble staff meal, supercharged with loads of pork bones and fish powder, captured a nation’s heart and created a ritual that, even after the boom’s peak, remains utterly delicious.