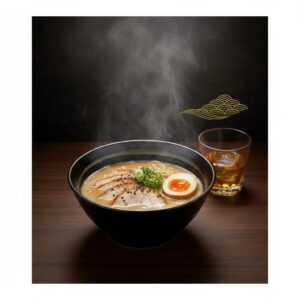

Yo, what’s the deal? It’s Shun Ogawa, and today we’re diving deep into one of Japan’s most iconic, and low-key bizarre, cultural exports: shokuhin sanpuru, or those plastic food models you see everywhere. You’ve seen them. You’re strolling through a shotengai, a classic Japanese shopping arcade, maybe in some electric Tokyo neighborhood or a chill side street in Osaka. Your senses are getting absolutely bombarded. The sounds, the smells, the sheer density of everything. Then you stop. You find yourself staring into a restaurant window, utterly captivated. Inside, under a soft spotlight, sits a bowl of ramen. The noodles are glistening, suspended perfectly in a rich, porky-looking broth. The chashu pork has that melt-in-your-mouth sheen. The soft-boiled egg is a perfect jammy orange. It’s the most beautiful bowl of ramen you have ever seen. And it’s completely, 100% fake.

Your brain kinda short-circuits for a second. The first thought is, “How?” The second is, “Why?” Why go to such insane lengths to create a plastic replica of a meal? In many places, a laminated photo or a text menu does the job just fine. But not in Japan. Here, the standard is a three-dimensional, life-sized, hyper-realistic sculpture of your potential dinner. It’s an art form that’s both incredibly practical and artistically over-the-top. It feels like a glitch in the matrix, a perfect copy of reality that’s almost too real. This isn’t just about showing you what’s on the menu. This is a statement. It’s a cultural artifact that tells you so much about the Japanese mindset—the obsession with detail, the deep-seated desire for clarity, and a unique approach to customer service that borders on performance art. It’s a world where pragmatism and aesthetic perfection had a baby, and that baby was a piece of plastic tempura. So, if you’ve ever found yourself hypnotized by a fake bowl of katsudon and wondered what’s really going on behind the scenes, you’re in the right place. We’re not just gonna look at the finished product; we’re going behind the curtain, into the workshops where this magic happens, to understand the craft, the history, and the very specific cultural vibe that makes shokuhin sanpuru a thing. Let’s get it.

If you’re now craving the real thing, you can experience the authentic atmosphere at one of Japan’s unique counter-only ramen shops.

The OG Flex: How Plastic Food Became a Thing

You might assume these food models are an age-old tradition, akin to ikebana or sumo. Not quite. The entire phenomenon is surprisingly modern, a 20th-century innovation that arose from a classic challenge: a major shift in Japan’s diet. It’s a tale of practicality, creativity, and one man’s lightbulb moment sparked by melting wax. This industry directly responds to a pivotal cultural and culinary transformation in Japan.

A Solution Born from Misunderstanding (and Wax)

Imagine this: it’s the late Taisho and early Showa eras, around the 1920s and early 1930s. Japan is rapidly modernizing. Western influences are flooding in, including Western cuisine. Dishes like omurice (omelet with rice), curry rice, and tonkatsu (pork cutlet) were becoming all the rage, especially in the upscale new department stores popping up in major cities. These department stores featured basement food halls, or depachika, serving as the heart of this culinary trend. However, there was a major challenge. The average Japanese person had no idea what these dishes looked like. A menu listing “omurice” in katakana was just an unfamiliar string of sounds if you’d never seen or tasted it. You couldn’t picture it or know what to expect. This caused hesitation and confusion among customers, which was bad for business.

Enter Takizo Iwasaki, a craftsman from Gujo Hachiman, a town in Gifu Prefecture that would later earn the title of the food sample capital. Legend has it that one evening in 1932, Iwasaki’s wife accidentally dropped some hot candle wax into cold water. He watched as the wax solidified instantly, capturing the ripples and texture of the water’s surface. Playing with it, he noticed it resembled a flower petal. Then, inspiration struck as he looked at a plate of his wife’s homemade omurice—a fluffy omelet over ketchup-fried rice. What if? He began experimenting, pouring colored wax into molds and onto water, painstakingly crafting a wax replica of the omurice. It was so realistic that he famously couldn’t tell it apart from the real dish at first glance. He realized he had discovered a powerful communication tool—no words needed. Just point to the wax omurice, and the customer instantly understands. It was a visual contract, a promise of the meal ahead. Iwasaki founded Iwasaki Mokei Seizo and began selling his creations to restaurants and department stores. The idea was a huge success, perfectly solving the problem, and soon restaurant windows throughout Japan were adorned with these silent, mouthwatering wax models.

From Wax to Vinyl: The Post-War Evolution

While the wax models were ingenious, they had drawbacks. Wax is fragile; it melts in summer heat, becomes brittle in the cold, and its colors fade under sunlight. Moreover, pests like cockroaches and mice sometimes found them tempting snacks. The industry’s real breakthrough came after World War II during Japan’s extraordinary economic growth. As the nation rebuilt, a new middle class with disposable income emerged, making dining out common rather than a luxury. Competition among restaurants became intense, and eye-catching window displays were vital.

It was then that the industry switched from wax to polyvinyl chloride (PVC), or vinyl as we know it today. This was transformative. PVC was far more durable, resisting heat, cold, and sunlight without degrading. Colors stayed vivid, and most importantly, it enabled an unprecedented level of detail. Artisans used silicone molds taken from real food to capture every pore on a strawberry, every grain of rice, every crisp crackle on fried chicken. This shift to PVC unlocked the hyper-realism we see now, evolving the craft from a clever marketing trick into a respected art form. This transition also reflected broader trends in Japan, which was becoming a global manufacturing powerhouse, renowned for high-quality electronics and automobiles. The same spirit of monozukuri—the relentless pursuit of perfection—was applied to plastic food models. A shokuhin sanpuru craftsman was akin to a top engineer at Toyota or Sony; all were obsessed with precision, quality, and flawless execution. The post-war transformation didn’t just improve the samples; it solidified them as an integral feature of the Japanese commercial scene and a testament to the nation’s dedication to craftsmanship.

It’s Not Just Food, It’s a Vibe: The Psychology of the Sanpuru

Alright, so here’s the history. It began as a practical business solution. Yet that doesn’t completely explain why it remains so widespread today, in an era of Instagram and digital menus. To understand that, you need to look deeper, into the cultural software underlying Japanese society. The food sample is not just a tool; it’s a tangible expression of core cultural values such as clarity, trust, and a strong desire to avoid friction in social interactions. It serves as the ultimate user interface for dining out.

Zero-Risk Ordering: The Ultimate User Interface

A key concept in Japanese society is the idea of avoiding meiwaku, which roughly means “trouble” or “bothering others.” The aim is to ensure social interactions are as smooth and frictionless as possible. This principle is evident everywhere: the silence on trains, the orderly queues, the constant apologies for minor inconveniences. The shokuhin sanpuru system perfectly embodies this principle applied to commerce. It’s focused on managing expectations and removing uncertainty. When you see a food sample in a window, you’re looking at a one-to-one promise of what will arrive at your table. The size, ingredients, and presentation—everything is there. There’s no vagueness. You won’t order the “Deluxe Seafood Platter” and end up with two sad shrimp and a lemon wedge. What you see is literally what you get. This generates what the Japanese call anshin-kan, or a sense of peace and security. As a customer, you can order with complete confidence. You don’t have to worry about language barriers, decipher confusing menus, or risk disappointment. You simply point and order. For the restaurant, it prevents complaints, misunderstandings, and dissatisfied patrons. It’s a system designed to promote maximum harmony and minimize stress for both sides of the transaction. This is in stark contrast to many Western dining experiences, where menu photos are often heavily stylized, exaggerated glamour shots of food. The sanpuru is not advertising; it’s a contract. It exemplifies a form of customer service, or omotenashi, that is proactive, aiming to anticipate and resolve your concerns before they arise.

The Art of “Shokunin”: Hyper-Realism as a Showcase

If the purpose were simply to show what a dish looks like, a decent plastic model would suffice. But that’s not what sanpuru are. They are hyper-realistic masterpieces because the people creating them aren’t mere factory workers; they are shokunin—master artisans. The shokunin concept is central to Japanese craftsmanship. It refers to someone who has devoted their life to perfecting a specific skill, pursuing mastery not for money or fame, but for its own sake. It’s a deep, almost spiritual commitment to their craft. The world of shokuhin sanpuru is filled with these artisans.

Producing a top-quality food sample is an extremely labor-intensive process that cannot be fully automated. It begins with the real dish, prepared perfectly by a chef. The artisans then carefully deconstruct it and create silicone molds of every component—each slice of green onion, every piece of meat, every single noodle. Liquid PVC is poured into these molds and baked until solid. But that forms only the base. The true artistry lies in the finishing touches. Each piece is hand-painted with incredible precision. An artisan will spend hours or even days perfecting the color gradients on a piece of grilled fish. They use airbrushes and tiny paintbrushes to replicate subtle char marks, glistening oil, and the translucency of raw tuna. They have developed secret techniques to mimic various textures. A spritz of special spray creates realistic condensation on a cold beer glass. A glossy coating gives a sauce its rich, moist look. The pursuit of realism is relentless. It’s a professional showcase, a source of immense pride. The goal is to craft a replica so flawless it can fool anyone. This dedication to detail embodies the shokunin spirit in action. It’s why a piece of fake lettuce can be regarded as a work of art and why this seemingly niche craft has endured and flourished for nearly a century.

Getting Your Hands Dirty: The Sanpuru Workshop Experience

Reading about this stuff is one thing, but to truly capture the vibe, you need to experience it firsthand. Throughout Japan, especially in places like Tokyo’s Kappabashi Kitchen Town or Gujo Hachiman, the industry’s birthplace, you can find workshops where you actually learn to make your own food samples. Entering one of these workshops is like stepping into a Willy Wonka factory for food enthusiasts. It’s a sensory overload of colored waxes, tubs of liquid vinyl, and rows upon rows of fake food that looks good enough to eat. This is where theory meets reality, and you develop a genuine appreciation for the cleverness and skill involved.

Stepping into the Matrix: What a Workshop is Really Like

A typical workshop is a blend of a science lab and an art studio. There’s a faint, sweet scent of heated plastic in the air. The workspaces are usually simple, often featuring a large basin of warm water, trays of colored wax or vinyl, and a few basic tools. The instructors are often veteran artisans who have been in the craft for decades. They move with quiet, practiced efficiency that’s mesmerizing to watch. Rather than just telling you what to do, they demonstrate techniques refined over generations. Usually, you get to choose what to make. The most popular and iconic beginner items are tempura and lettuce, thanks to their surprisingly simple processes that produce incredibly realistic results. It’s pure magic seeing liquid wax transform into a crispy shrimp tempura right before your eyes. It feels less like crafting and more like a chemistry experiment gone deliciously right. The experience demystifies the process while deepening your respect for the artisans who do this professionally. You realize that while the basic techniques are learnable, mastering them to a professional level would take a lifetime.

The Tempura Trick: Mastering the Wrist Motion

Making tempura is a classic workshop experience and a real thrill. Here’s how it goes: you start with a pre-made plastic core, like a shrimp or slice of sweet potato. The real magic is in the batter. An instructor shows you how to take a small cup of melted, pale-yellow wax. You hold the plastic shrimp by its tail with tongs and, from about a foot high, slowly drizzle the warm wax over it into a basin of hot water (around 42°C). As the wax hits the water, it instantly solidifies into a lacy, bubbly coating that looks exactly like fried tempura batter. It’s almost magical. The trick lies in the pour’s speed and height—too fast and it turns into a blob, too slow and it doesn’t form the right texture. You then gently wrap the lacy wax coating around the shrimp core while still in the water, shaping it to look freshly fried. You pull it out, and voilà—perfect shrimp tempura. The technique is simple in concept but so visually effective it makes you laugh out loud. You instantly grasp the ingenuity that launched this entire industry.

That Lettuce Life Hack You Never Knew You Needed

Another mind-blowing workshop staple is making a head of iceberg lettuce, which feels like pure alchemy. You start with a large, shallow basin of warm water. Your instructor shows you how to ladle a thin layer of white wax onto the water’s surface, followed by a layer of green wax on top. The wax spreads into a thin, delicate film floating on the water, representing a single lettuce leaf. Then comes the wild part: you put your hands in the water at one end of the basin and carefully drag the wax film toward you. As you pull, the film naturally crumples and folds, creating the delicate, crinkly texture of a real lettuce leaf. You continue pulling and rolling it until you have a long, sausage-shaped bundle of crinkled wax. The instructor then places it on a cutting board and slices it in half. The cross-section reveals a stunningly realistic pattern of layered, curled leaves, just like a real head of lettuce. The effect is so perfect and the process so counterintuitive, it feels like performing a magic trick. It’s a testament to decades of observation and experimentation to replicate nature with such simple materials.

The Modern Sanpuru: From Restaurant Window to Global Meme

In a world dominated by high-resolution food photography and online review apps, are shokuhin sanpuru still relevant? The answer is a resounding “yes,” though their role is evolving. While they continue to fulfill their primary purpose in many traditional restaurants, particularly in tourist areas and for older generations, they have also taken on a vibrant new life. They’ve surpassed their original function to become pop culture symbols, quirky fashion accessories, and even respected works of art. The sanpuru have successfully adapted to the 21st century.

More Than Just Display: The Evolution

The most noticeable change is the surge of sanpuru as souvenirs and merchandise. Wander through any major tourist spot in Japan, and you’ll find shops selling incredibly realistic food sample keychains, phone cases, magnets, and even jewelry. You might purchase a tiny sushi earring or a slice of bacon bookmark. These items are hugely popular with both foreign tourists and young Japanese people. They tap into the culture of kawaii (cuteness) and the love for quirky, unique accessories. It’s a way to bring home a piece of this distinctive Japanese craft. Beyond these trinkets, the expertise of sanpuru artisans is being applied in other fields. Their skill in creating hyper-realistic replicas is valuable in medical training, where models of organs and tissues are used for surgeons to practice on. They’re also employed in nutritional education, with meal models helping teach children about balanced diets and portion control. In a sense, the craft is returning to its roots as a means of communication and education, only now in fresh and unexpected contexts. Some high-end sanpuru are even gaining recognition as art, showcased in galleries and museums worldwide, admired for their exquisite craftsmanship and as symbols of a unique facet of modern Japanese culture.

Checking the “Why Japan is Like This” Vibe

To bring it all together, when you look beneath the surface, shokuhin sanpuru is much more than just plastic. It’s a compelling case study for understanding the modern Japanese mindset. This physical object embodies several core cultural values, and once you recognize them, you can’t unsee them. First, there’s the deeply entrenched value of Omotenashi, or Japanese hospitality. This goes beyond mere politeness; it’s about anticipating others’ needs and ensuring their comfort and ease. A food sample does exactly that: it removes confusion, anxiety, and potential disappointment from the ordering experience, creating a smooth and pleasant visit for the guest. Second, it represents Monozukuri, the spirit of manufacturing and craftsmanship. This cultural drive aims to create things not just well, but perfectly. The obsessive attention to detail, continual refinement of techniques, and pride in the finished product—whether a car or a plastic piece of tuna—is a hallmark of Japanese industry and art. The sanpuru stands as a small, everyday monument to this spirit. Lastly, it offers Anshin-kan, a vital sense of relief and security. In a world filled with uncertainties, the sanpuru provides consistency. It’s a guarantee. In a society that often values predictability and stability, this is profoundly reassuring. It’s a system built on trust and transparency. So next time you find yourself gazing at a restaurant window in Japan, captivated by a glossy, fake bowl of ramen, remember you’re not just seeing a clever marketing gimmick. You’re looking at a piece of cultural machinery. You’re witnessing a distillation of the principles of hospitality, craftsmanship, and psychological comfort that, in many ways, define Japan. And once you grasp that, you’re one step closer to understanding the whole vibe.