Alright, let’s get real for a sec. You’ve seen the picture, right? The one that floods your feed every winter. A Japanese macaque, looking blissfully unbothered, soaking in a natural hot spring while the world around it is a literal snow globe. Or maybe it’s a person, their shoulders dusted with fresh powder, steam rising around them like something out of an anime. The caption is always something simple, like “Winter in Japan,” and you’re left thinking, “Okay, that looks epic, but is it for real? Is sitting half-naked in a blizzard while you boil yourself actually a good time?” It’s a valid question. The whole scene feels almost too perfect, too aesthetic. It’s the kind of thing that seems designed for Instagram, a fleeting moment of manufactured zen. But what if I told you that this experience, the yukimi-buro (雪見風呂) or snow-viewing bath, is one of the most legit, deeply rooted cultural cheat codes to understanding Japan’s whole deal with nature, seasons, and finding beauty in the most extra of circumstances? It’s not just a hot bath in the snow. Nah, it’s a full-blown conversation with the environment, a physical manifestation of a philosophy that’s been brewing for centuries. This isn’t about getting clean. It’s about getting in tune. Forget what you think you know about spas and jacuzzis. We’re about to dive deep into a world where extreme temperatures collide to create something that’s, no cap, pretty profound. It’s a sensory overload in the best way possible, a practice that forces you to be right here, right now, in a way that scrolling through those pictures never could. So, the question isn’t just “is it worth it?” The real question is, “what’s actually going on here?” What is it about this specific, slightly insane combination of fire and ice that speaks so deeply to the Japanese soul? Let’s break it down.

To truly grasp this obsession with extreme temperatures, you need to understand the cultural phenomenon behind that viral snowy rotenburo photo.

The Contrast is the Point: A Symphony of Opposites

First off, we have to talk about the main event: the absolute physical insanity of it all. Your brain can barely process the information it’s taking in. It’s a full-on sensory paradox. You’re not just witnessing the snow; you’re feeling it, hearing it, even tasting it in the air, all while being wrapped in water heated to 42 degrees Celsius (about 107 Fahrenheit for those who prefer non-metric). It’s a vibe built entirely on the intense, beautiful clash of opposites.

The Thermal Shock and Awe

Picture this. You’re in a ryokan, a traditional Japanese inn, probably tucked away deep in the mountains of Tohoku or Nagano. It’s already cold inside, but then comes the walk of faith. You strip down in a changing room, grab your tiny modesty towel, and slide open a door that leads to the outside. And BAM. The air hits you. It’s more than chilly; it’s a physical force. That deep-winter, high-altitude cold that steals your breath and makes your skin prickle right away. Every nerve screams “ABORT! THIS IS A TERRIBLE IDEA!” You take a quick, awkward scuttle over frozen stones or wooden planks, your feet protesting, headed for that cloud of steam rising off a rock-bordered pool. This moment isn’t glamorous. It’s the price you pay.

Then you slip into the water. The first sensation is a jolt of pure, raw relief. It’s so intense it nearly borders on pain for a fraction of a second before softening into a deep sense of release. The heat seeps into your bones, unknotting muscles you didn’t even realize were tense from the cold. Your body enters a happy state of confusion. Your lower half submerges in hot, volcanic, mineral-rich water, while your head and shoulders remain exposed to the freezing air. You feel snowflakes landing on your face, your hair, your shoulders, melting almost instantly on your skin. It’s a constant conversation between two elemental forces, with your body caught right at the intersection. Blood rushes to your skin, creating a shield against the cold, while your core stays profoundly warm. It’s a sensation of being both revitalized and deeply relaxed. Your body is active, adapting, alive in a way rarely experienced when sitting in a climate-controlled room. This isn’t the passive relaxation of a spa. It’s active. It forces an extreme mindfulness as your body processes so much sensory input.

A Visual and Auditory Feast

The visual contrast is what gets photographed, but photos don’t do it justice. It’s not a still image. You watch heavy, thick snowflakes drift down from a grey sky, settling on the dark, wet rocks around the onsen, gradually building a pristine white border. Steam rises from the water, meeting the cold air in billows so thick you can barely see across the bath. It’s like being inside a living, breathing ink wash painting, a suibokuga. The world distills to monochrome: the white snow, black rocks, grey sky, and the milky, sometimes blue- or green-tinted mineral water. Any other color—like the red of a Japanese maple branch cradling a mound of snow—pops with stunning vibrancy.

But the sound… the sound is what truly lifts it. Or more precisely, the absence of it. Freshly fallen snow is a top-tier sound absorber. It sucks up ambient noise, creating a profound, heavy silence rarely found in cities. You’re left with a minimalist soundscape: the gentle lapping of water as you move, the near-imperceptible whisper of snowflakes landing on the bath’s surface, your own breathing amplified in the stillness. Occasionally, the creak of a snow-laden bamboo branch. It’s a silence so deep it feels sacred. Here, you can really hear yourself think—or better yet, not think at all. You’re simply… there. The silence isn’t empty; it’s full. It’s a presence itself, starkly contrasting the endless noise of modern life. This blend of sensory input—the thermal shock, the monochrome visual world, the profound quiet—creates a state that’s hard to replicate. It’s at once grounding and transcendent. You feel intensely connected to your body and, at the same time, to the vast, indifferent, breathtaking power of nature.

More Than a Season, It’s a Religion: Decoding ‘Kisetsukan’

So, why go through all this effort? What makes this particular seasonal experience so highly esteemed? To truly grasp it, you need to understand a fundamental concept in Japanese culture: kisetsukan (季節感). This is roughly translated as “season-feeling” or “a sense of the seasons,” though that hardly captures its full meaning. It’s not just about recognizing that it’s winter—it’s a profound, almost spiritual dedication to actively engaging with and honoring the distinct phases of the year. In the West, seasons are often something to be endured or managed. We winter-proof our homes and complain about the cold; we turn up the air conditioning and hide from the summer heat. In Japan, however, the mindset is different. It’s about embracing the season. It’s about discovering the unique beauty and activities that exist only within that brief window of time.

The Seasonal Big Four

Consider this: the most iconic aspects of Japanese culture are all tied to the seasons. Spring isn’t just spring; it’s hanami (花見), the tradition of cherry blossom viewing. People don’t simply note, “Oh, pretty flowers.” They throw huge parties, have picnics, and hold festivals to sit beneath the sakura trees and admire their exquisitely fleeting beauty. Summer brings hanabi (花火), grand fireworks displays, and the loud chorus of cicadas. Autumn centers on momijigari (紅葉狩り), or “red leaf hunting,” where people will travel for hours to witness breathtaking mountainsides ablaze in crimson and gold maple leaves.

Winter’s hallmark tradition is yukimi (雪見), snow viewing. The ultimate experience—its pinnacle—is enjoying it from a hot spring. Yukimi-buro is not just an activity; it is the quintessential winter ritual. It completes the cycle. Each of these customs goes beyond a scenic view—they are ceremonies that mark the passage of time and connect people to the natural world’s rhythms. It’s a way to say, “We acknowledge you, winter. We honor the unique, harsh beauty you bring, and we choose to confront it joyfully.” This profound seasonal appreciation permeates every aspect of life. Food is intensely seasonal; you eat what’s at its absolute peak right now. Art, poetry, and even kimono patterns shift to reflect the current season. So when you see someone in a yukimi-buro, you’re witnessing more than a relaxing bath—you’re observing someone engaging in a centuries-old cultural tradition of seasonal reverence.

A Fleeting, Perfect Moment

This devotion to the seasons is deeply intertwined with the Buddhist idea of impermanence, or mujō (無常). Cherry blossoms are beautiful precisely because they last only about a week. Autumn leaves captivate because soon, the trees will be bare. The yukimi-buro experience follows the same principle. The snow will melt. The perfect silence will end. The exact conditions that create the moment—the right snowfall, the ideal water temperature, the crisp, still air—are transient. You can’t capture it or save it for later. You must be fully present to savor it as it happens. This makes the experience precious. It’s not a commodity to consume but a fleeting moment to witness. It trains you to find beauty not in permanence or flawlessness, but in life’s transient, imperfect flow. This represents a profound shift from a Western mindset that often seeks to control and tame nature, to preserve and prolong. The yukimi-buro is an act of surrender to the present, a celebration of the fact that nothing endures.

The Sacred Soak: Why Bathing is a Big Deal

Alright, we have sensory overload and seasonal fascination covered. But we need to confront the obvious topic: the bath itself. For most people outside Japan, bathing is purely functional—you do it to get clean. Occasionally, there might be a relaxing bubble bath with a candle, but it’s mostly a private, utilitarian routine. In Japan, however, bathing—especially communal bathing in an onsen (温泉)—belongs to an entirely different world. It’s a practice deeply embedded in the spiritual and social fabric of the country, with the yukimi-buro as its most striking embodiment.

Purity, Nature, and the Gods

To grasp the onsen, one must look back at Shinto, Japan’s native religion. Shintoism is an animistic faith, meaning it holds that gods, or kami (神), inhabit natural objects and phenomena—mountains, rivers, trees, rocks, and indeed, volcanically heated springs. These natural spots are therefore sacred. Soaking in an onsen isn’t just about hot water on your skin; it’s about immersing yourself in a sacred, life-giving element. It’s a way to connect with the kami of that place.

Moreover, Shinto emphasizes purity—both physical and spiritual. Before entering a shrine, one performs temizu, a purification ritual washing hands and mouth. Bathing carries a similar spiritual significance. It acts as misogi (禊), a ritual cleansing that removes not only physical dirt but also the spiritual grime of everyday life—stress, fatigue, misfortune. This is why onsen etiquette is strict and non-negotiable. You MUST wash your entire body thoroughly with soap and water at the washing stations before entering the onsen bath. The onsen water is meant for soaking, healing, and spiritual communion—not cleaning. Entering it with a soapy or dirty body is a serious sign of disrespect, not only to fellow bathers but also to the sacredness of the water. Once understood, the ritual becomes clear: a two-step process of first cleansing mundane dirt, then entering the sacred water to purify the spirit.

From Healing to Social Hub

Beyond spirituality, onsen have a longstanding history as healing places. This practice is known as tōji (湯治), or hot water therapy. For centuries, people—from samurai recovering from battle wounds to farmers with sore joints—have made pilgrimages to onsen towns, staying for weeks and soaking multiple times daily to treat various ailments. Each onsen has a unique mineral makeup, or senshitsu (泉質), believed to benefit different conditions. Near the baths, you’ll often find charts detailing properties—sulfur for skin issues, iron for anemia, radium for joint pain. While scientific proof varies, the cultural faith in the healing powers of onsen is strong. Soaking in a yukimi-buro is thus seen not only as a beautiful experience but also as absorbing the earth’s potent healing energy during winter, strengthening body and spirit.

There’s also the social element. The concept of hadaka no tsukiai (裸の付き合い), meaning “naked communion” or “naked friendship,” is essential. In a society often formal and hierarchical, the onsen acts as the great equalizer. Once clothes come off, everyone is simply human. Ranks and titles vanish, enabling more open, relaxed conversations. While quiet contemplation is common, onsen also serve as spaces for family bonding and friends to reconnect. Stripping away clothing and social status fosters a more direct, genuine connection. Thus, a yukimi-buro isn’t necessarily a solitary, meditative experience; it can be profoundly communal—a shared appreciation of a beautiful moment that strengthens social ties.

It’s Giving Wabi-Sabi: The Aesthetics of a Snowy Bath

You can’t discuss a Japanese aesthetic experience without mentioning the heavy hitter: wabi-sabi (侘寂). This term is often loosely and incorrectly used to describe anything vaguely rustic or minimalist. However, in the context of a yukimi-buro, it is entirely fitting. Wabi-sabi represents a worldview centered on embracing transience and imperfection, finding beauty in the humble, weathered, and unconventional.

Embracing the Imperfect

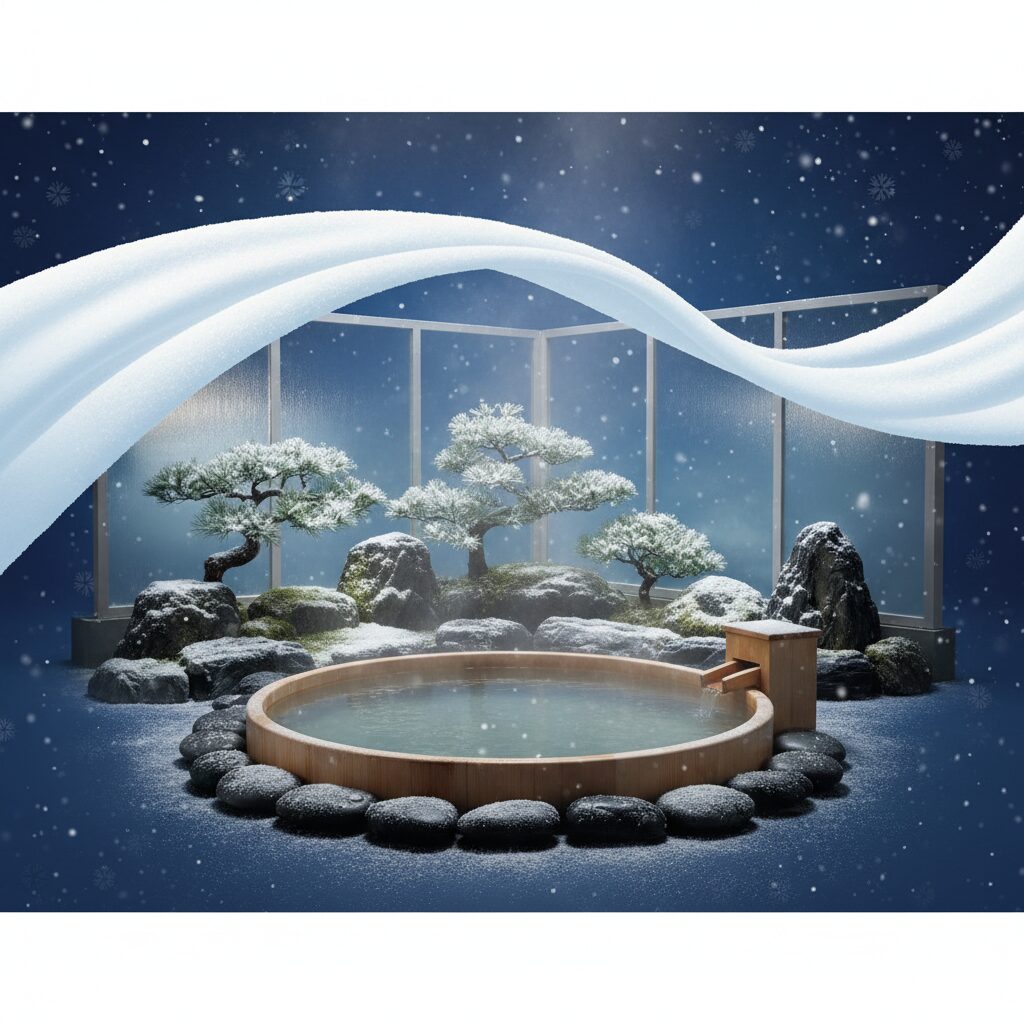

Consider the traditional yukimi-buro setting. It’s not a flawlessly tiled, infinity-edge pool at a luxury resort (though those exist). The ideal, most treasured yukimi-buro is a rotenburo (露天風呂), an outdoor bath that feels as if it was shaped directly by nature. The tub might be crafted from rough stone, perhaps moss-covered, or fragrant hinoki cypress wood that has aged gracefully. The surrounding landscape isn’t carefully manicured. Instead, it’s wild—bare trees, frozen waterfalls, and scattered rocks arranged naturally and without artifice. This represents the “wabi” aspect—a rustic simplicity and understated elegance grounded in authenticity and humility.

Then, there is the “sabi” element—the beauty that emerges with age and the passage of time. It’s the patina on the stones, the way snow clings to the uneven branches of an old pine. The overall experience itself embodies wabi-sabi. Snow falls erratically, steam blurs the view, the cold bites sharply. It is not a perfect, controlled moment—and that’s precisely the point. The profound sense of peace and beauty arises not despite the imperfections, but because of them. You’re not gazing at a perfect painting; you’re immersed in a living, shifting, wonderfully imperfect scene.

Mono no Aware: The Gentle Sadness in It All

Closely connected is the idea of mono no aware (物の哀れ), often translated as “the pathos of things.” It conveys a tender sadness or wistfulness about life’s impermanence. It’s the feeling you experience as the last cherry blossom petal drifts down, or as the sun sets. It’s not sorrowful in a bleak way, but a deep, empathetic appreciation for the fleeting beauty of a moment. Watching a snowflake land on the hot onsen water and instantly vanish is an ideal metaphor for mono no aware. It existed, it was beautiful, and then it was gone. The entire yukimi-buro experience serves as a compact lesson in this philosophy. This is why it resonates far more deeply than just a relaxing bath—it is an emotional and philosophical immersion. It connects you to the vast, beautiful, and bittersweet cycle of life, death, and renewal, all from the warm embrace of a hot bath. It’s a moment that feels both insignificant—you are a small warm being within a vast, frozen world—and profoundly significant, as the conscious witness to this fleeting beauty.

Keeping It 100: The Reality Behind the ‘Gram

Now, for a reality check: Is every yukimi-buro experience a life-changing, deeply philosophical moment? Certainly not. It’s crucial to distinguish the idealized image from the actual reality on the ground, as expectations can either enhance or ruin the experience.

The Logistical Challenge

First, reaching these locations can be quite the ordeal. The best snow-viewing onsen are, by nature, situated where heavy snowfall occurs. This often means remote mountain villages accessible only via a combination of Shinkansen, local trains, buses, and finally a shuttle from the ryokan. Winter travel in Japan is susceptible to disruptions from heavy snow, so building flexibility into your itinerary is essential. It’s not something you can do as a day trip from Tokyo; it requires a real commitment.

Second, it can be pricey. Staying overnight at a high-quality ryokan with a renowned rotenburo can cost a significant amount. This typically includes an elaborate multi-course kaiseki dinner and breakfast, making it an all-encompassing experience, but definitely a splurge rather than a casual visit.

Managing the Experience

Then there’s the bath itself. The “getting in” moment we mentioned? It can be unexpectedly and sharply cold. Hesitation can make you freeze—decisiveness is key. Also, you might not have the bath to yourself. While some ryokans offer private onsen (kashikiri-buro) bookable in advance, the main, most scenic baths are usually communal and separated by gender. Depending on the time, you could be sharing that peaceful moment with a dozen others. This isn’t inherently negative—it’s part of the social experience—but if you envision a solitary soak, you may need to adjust your expectations or seek out a ryokan that offers private baths.

The nudity aspect is, naturally, significant for many first-timers. There’s no way around it: onsen strictly prohibit swimsuits. The small towel provided is for washing and modesty while walking but is never meant to be submerged. The best advice is to embrace it. Understand that no one is looking at you or cares; everyone is there to unwind, and staring is highly impolite. After a few minutes, any self-consciousness tends to fade, but it’s a cultural barrier you should be ready to overcome.

Lastly, snow itself is never guaranteed. You might reserve your trip months ahead, hoping for picturesque snowy scenery, only to encounter bare branches or even freezing rain. It’s a gamble with nature, which, in a way, is part of the entire wabi-sabi philosophy. You can’t force the perfect moment; you simply have to be fortunate enough to experience it.

The Afterglow: The Ritual Continues

The yukimi-buro experience doesn’t end once you step out of the water. The post-onsen ritual is equally important and, honestly, just as enjoyable. Pulling yourself away from the volcanic warmth and making a swift dash back to the changing room is challenging, but the sensation that follows is exquisite.

Yukata, Milk, and a Feast

After drying off, you’ll slip into a yukata, a lightweight cotton robe provided by the ryokan. Your body buzzes with a warmth that radiates from within. This sensation, known as hoka hoka (ほかほか), is a deep, thorough warmth that lingers for hours. Your skin feels soft, your mind clear, and you’re utterly relaxed, with jelly-like legs.

Rehydrating is a classic post-onsen custom. Vending machines are everywhere around onsens, and the popular choices are ice-cold milk (often in classic glass bottles) or a crisp Japanese beer. There is something viscerally satisfying about gulping down cold milk or beer when your body is glowing with heat—a sensory contrast that feels uniquely refreshing.

You then drift back to your tatami mat room in a blissful, exhausted state. This is when the next phase of the experience begins: the kaiseki dinner. This traditional multi-course meal is a work of art, with each dish carefully crafted using seasonal, local ingredients and presented on beautiful ceramics that reflect the season. Enjoying a winter kaiseki—with hearty hot pots, delicate sashimi, and grilled fish—after a long soak in a yukimi-buro is a comfort and satisfaction that’s hard to put into words. The entire ryokan experience is a thoughtfully curated journey, with the onsen at its heart.

So, Why Bother?

Ultimately, we return to the original question: why is this experience so crucial to understanding Japan? Because the yukimi-buro serves as a cultural microcosm. It is a tangible lesson encompassing everything we’ve discussed. In a single act, you engage with Shinto ideas of purity and nature, the Buddhist reverence for impermanence, the aesthetic values of wabi-sabi, the nation’s deep connection to the seasons, and the social tradition of communal bathing. This experience pushes you out of your comfort zone—both literally and metaphorically—and requires you to be fully present. You can’t scroll through your phone in an onsen. You can’t multitask. You are compelled to simply sit, feel the water, watch the snow, and listen to the silence. It offers an antidote to the alienation of modern life. It’s not merely about observing the snow; it’s about allowing the raw, unfiltered reality of a harsh and beautiful season to wash over you and through you, until the boundary between you and the outside world softens at the edges. And that, far more than any flawless photo, is a feeling worth pursuing.