Alright, let’s spill the tea. You’ve seen the pics, right? The insane drone shots of Japan buried in perfect, fluffy powder. You’ve seen the ski resorts, the snow monkeys chilling in hot springs, and maybe even the poetic black-and-white photos of traditional houses looking like gingerbread cottages frosted with an impossible amount of snow. It’s a whole aesthetic. The ‘Yukiguni,’ or Snow Country, looks like a winter wonderland fantasy, a serene, almost silent world painted in monochrome. And look, it can be that. But if you think that’s the whole story, you’re only seeing the highlight reel. The real question isn’t “Is the snow in Japan really that deep?” The real question is, “How does living under a literal blanket of frozen water for half the year shape a person, a community, a whole culture?” Because trust me, the postcard version doesn’t even begin to cover the grind, the genius, and the deep, deep resilience that defines life in these regions. Before we dive into the blizzard of reality, let’s get our bearings. We’re not talking about a casual dusting in Tokyo. We’re talking about the western coast of Japan’s main island, Honshu, particularly regions like Niigata, Yamagata, and Akita. This area gets slammed by moisture-heavy winds coming off the Sea of Japan, which then hit the central mountain range and dump just an absurd amount of snow. It’s one of the snowiest inhabited places on Earth. Forget what you think you know about a ‘snow day’. Here, the snow is the main character, and it runs the show. It’s the boss, the landlord, and the silent partner in every aspect of life. So, let’s get past the Instagram fantasy and dig into the raw, unfiltered truth of what it means to be from the Yukiguni.

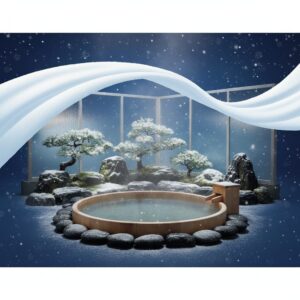

To truly understand this deep cultural relationship with the snow, one must experience the profound local tradition of yukimi-buro.

The White Demon: When Snow Isn’t Your Friend

First, we need to completely rethink the concept of snow. For tourists, snow means recreation—fun and fleeting. But for the people of Yukiguni, snow is an unyielding, heavy, and occasionally deadly force of nature they must confront for months at a time. They have a word, ‘gousetsu,’ meaning ‘heavy snow,’ but its nuance is closer to ‘typhoon-level snow.’ It’s a natural disaster that moves slowly and silently. The soft, fluffy powder seen in ski videos? That’s the pleasant side. The reality is often ‘botayuki’—thick, wet snow falling in heavy clumps. It sticks to everything and is incredibly heavy. Imagine waking up to find your entire surroundings smothered by a blanket of wet concrete. That’s the experience.

The Daily Grind: Yukikaki, The Hidden Workout

The defining winter activity in Yukiguni is ‘yukikaki’—snow shoveling or clearing. This isn’t a quick 15-minute chore to clear your doorstep. It’s a demanding, hours-long daily ritual. In the hardest-hit areas, several meters of snow often pile up. Snowbanks tower over houses, burying cars, road signs, and the ground floors of buildings. The work is relentless. You clear a path, and within an hour, it’s covered again. You clear your roof to prevent collapse beneath the massive weight—a perilous task called ‘yuki-oroshi’—and all that snow forms a new mountain you must shift from the ground. It’s a Sisyphean battle against the elements.

This isn’t just a matter of inconvenience; it’s life or death. Paths must remain open for emergency vehicles. Heater vents need clearing to avoid carbon monoxide poisoning. Elderly residents, who make up a large portion of the rural population, may be unable to perform this work, so community cooperation is essential. The sound of a Yukiguni morning isn’t birdsong; it’s the scrape-scrape-scrape of shovels, the hum of snow blowers, and the roar of heavy machinery clearing main roads. It’s a war of attrition, with the human body as the main weapon. This daily struggle builds a unique toughness—a physical and mental resilience that city dwellers rarely understand. The quiet satisfaction of a cleared path, the steam rising from your breath in the frigid air—these moments define the Yukiguni spirit.

Beyond Shoveling: The Infrastructure of Snow

Living with such heavy snow demands incredible infrastructural adaptations. In towns like Tokamachi in Niigata, main roads have built-in sprinkler systems that spray warmer groundwater to melt snow, creating steaming, snow-free arteries through the otherwise buried landscape. You’ll also find ‘ganki-zukuri,’ traditional covered walkways extending from building fronts, forming sheltered tunnels that allow pedestrians to navigate the town without wading through waist-deep snow. This is a brilliant, centuries-old answer to a persistent challenge. Traffic lights are installed vertically to prevent snow buildup from weighing them down. Houses are built on raised foundations, often with main entrances on the second floor, as the first floor remains inaccessible for much of the winter. Even road guardrails are different—they’re marked with tall, candy-striped poles so snowplow drivers can identify the road’s edge beneath two meters of snow. These aren’t just quirky features; they are vital survival tools, an environment shaped directly by the overwhelming presence of snow. Maintaining a sense of normal life here is a constant, costly, and labor-intensive battle. The annual snow removal budget in these prefectures is enormous—a hefty financial toll that comes with living in the Snow Country.

Ingenuity Born from Isolation: The Yukiguni Glow-Up

When you’re snowed in for four to five months each year, you can either go stir-crazy or get creative. The people of Yukiguni chose the latter. The long, dark winters, which made farming impossible, became a time of intense concentration, craftsmanship, and cultural growth. The very isolation and hardship brought on by the snow became the spark for remarkable ingenuity and artistry. This isn’t just about “making the best of a bad situation”; it’s about a culture that learned to transform a dormant season into a period of creation.

Preserving Life: The Art of Winter Food

Before modern logistics and convenience stores, the question of how to eat during winter was crucial. The solution was a refined culture of food preservation. Yukiguni’s flavors stem from this necessity. Think of ‘tsukemono’ (pickles) elevated to another level. Vegetables harvested in autumn were salted, fermented in rice bran, or hung to dry, turning them into nutrient-dense staples that could endure the long winter. Wild mountain greens, or ‘sansai’, foraged in spring, were also preserved, providing essential vitamins and a taste of the green earth when the world outside was white. This preservation culture was about more than survival; it was about capturing the essence of other seasons to brighten winter’s darkness. A simple meal of rice, miso soup, and an array of colorful, flavorful pickles represented a triumph of foresight and skill. Even snow itself was employed as a tool. ‘Yukimuro’ are natural refrigerators—storehouses filled with snow—that keep a stable, high-humidity, near-freezing environment year-round. Food stored in a yukimuro, such as vegetables or aged meat and fish, is not merely preserved; its flavor evolves. Starches in vegetables slowly convert to sugars, making them sweeter and more delicious. This low-tech, sustainable method produces remarkably exquisite results.

This bond with the environment is especially evident in the world of sake. Niigata is famed for producing some of Japan’s finest sake, and this is no coincidence. The key ingredients are exceptional rice and incredibly pure water. The heavy snowfall melts in spring, filters through mountains for decades, and emerges as soft, pristine water perfect for brewing sake. The cold, consistent winter temperatures are ideal for the slow fermentation needed for premium ginjo and daiginjo sake. The ‘toji’ (master brewers) of Niigata are legendary, their craft refined during the long agricultural off-season. A sake brewery was more than just a business; it was a vital source of winter employment and a cornerstone of the local community.

Weaving Time: The Birth of Winter Crafts

What else do you do when you’re confined indoors for months? You perfect a craft. Yukiguni regions are renowned for their textiles, particularly high-quality woven fabrics. One of the most celebrated is ‘Echigo-jofu’, a lightweight, breathable hemp fabric from the Uonuma region of Niigata. The entire process is deeply connected to the snow. During winter, hemp fibers are spun into thread by hand. After weaving, the fabric is washed in the river and then laid out on snowfields (‘yuki-zarashi’) for ten to twenty days. The sun’s action on the snow releases ozone, which naturally bleaches the fabric to a brilliant white without harming the fibers. It’s a surreal and beautiful sight: long bolts of tan-colored fabric stretched across vast white fields, a testament to a process that perfectly blends human skill with the natural environment. This was more than a hobby; it was a crucial source of income for farming families—a way to turn the dead time of winter into valuable products that could be sold in spring. This same principle extends to many other regional crafts, from intricate woodwork to handmade paper. The patience, precision, and remarkable dexterity required for these arts were cultivated in the quiet, focused atmosphere of a snowbound home.

The Yukiguni Konjo: A Mindset Forged in White

The ongoing struggle with and adaptation to snow shapes more than just houses and food; it shapes people. It nurtures a particular mindset, a regional character often called ‘Yukiguni konjo’—the Snow Country spirit. This is a complex mix of stoicism, patience, reliance on community, and a profound, almost spiritual connection to the cycles of the seasons.

The Art of Endurance: Gaman and Shikata Ga Nai

Two concepts are central to understanding the Japanese psyche overall, but they take on special significance in Yukiguni: ‘gaman’ and ‘shikata ga nai’. ‘Gaman’ is commonly translated as ‘endurance’ or ‘perseverance’, but it carries deeper meaning. It involves bearing the unbearable with quiet dignity. The relentless, backbreaking task of yukikaki perfectly exemplifies gaman. Complaining is not an option; you simply do it because it must be done. It’s a shared hardship silently understood by everyone. ‘Shikata ga nai’ means ‘it cannot be helped’. This phrase is not an expression of defeat but one of practical acceptance. You cannot stop the snow from falling or wish away the winter. Instead, you accept reality and work within its limits. This mindset is not passive; it focuses your energy on what you can control—your shovel, your community, your craft—rather than wasting it on what you cannot, like the weather. Outsiders often misinterpret this stoicism as coldness, but in truth, it is a vital coping mechanism and a source of inner strength.

It Takes a Village: The Power of Community

In a Tokyo apartment complex, you might not know your neighbor’s name. In a Yukiguni village, your neighbor is your lifeline. The environment’s severity makes community cooperation essential. You shovel your elderly neighbor’s walkway not simply out of kindness but because they could literally perish if snowed in. People informally keep watch over one another. If someone’s lights are off or there’s no smoke from their chimney, someone will check on them. This mutual dependence fosters incredibly close-knit communities. Festivals and local events, especially those marking the end of winter, are celebrated with a collective joy that is difficult to put into words. When the snow finally melts (‘yukidoke’) and the first ‘fukinoto’ (butterbur shoots) emerge from the muddy earth, the sense of relief and renewal is deeply felt. It’s a shared communal rebirth. This profound reliance on each other is a beautiful and powerful aspect of Yukiguni culture—a social fabric as tightly woven as the textiles they produce.

A Different Rhythm: Living by the Season

Life in the Snow Country follows a rhythm largely lost in modern urban living. The seasons represent more than temperature changes; they are distinct chapters in the year demanding different activities, foods, and mindsets. Winter calls for introversion, hard work, and quiet focus. Spring bursts with life and frantic activity—planting rice, foraging mountain vegetables, repairing winter’s damage. Summer is lush, green, and humid, a short but intense growth period. Autumn is the harvest time, for preparing and giving thanks, stocking up for the coming white siege. This cyclical existence fosters a deep bond with the natural world. You learn to read the sky, sense changes in the wind, and notice subtle signs that signal seasonal shifts. It’s a grounded, elemental way of life, where human activity remains in constant dialogue with the environment. There is profound wisdom in this rhythm, an understanding that life is a cycle of hardship and joy, dormancy and growth. The vibrant green of spring cannot exist without the crushing white of winter.

Modern Yukiguni: The Great Thaw and the New Freeze

Today’s Snow Country stands at a crossroads, confronted with a complex blend of old and new challenges. The very forces that once shaped its unique culture—isolation and hardship—are now endangering its future. However, a new generation and fresh ways of thinking recognize immense value in the Yukiguni way of life and aim to reinvent it for the 21st century.

The Challenges: Depopulation and a Warming World

The greatest threat to Yukiguni is not the snow itself, but the dwindling population. Like many rural areas in Japan, these regions are grappling with severe ‘kaso’ (depopulation) and ‘koreika’ (aging society). Unsurprisingly, the young are often drawn to the conveniences and opportunities offered by larger cities. The hard physical labor and isolation inherent in traditional Yukiguni life make it a difficult choice in an era of digital connectivity and global careers. Who will clear the snow when mostly elderly people remain in the villages? Who will sustain traditional crafts and farming practices? This is the existential question looming over many communities. On top of that, climate change adds a new layer of uncertainty. While less snow might seem like a benefit, the reality is more complicated. The region’s economy, especially its large ski tourism sector, relies on consistent, heavy snowfall. Erratic winters with less snow or more rain can be disastrous. It also disrupts the delicate ecological balance critical to local agriculture and sake brewing. The ‘white demon’ they’ve known for centuries is becoming unpredictable and erratic.

Reinvention and Rediscovery: The Future Vibe

But it’s not all bleak. Absolutely not. There’s a growing movement to rebrand and revitalize Yukiguni. The rise of remote work has enabled some young professionals and families to relocate to these areas, seeking better work-life balance, closer ties to nature, and safer environments to raise children. They bring fresh energy and ideas, opening modern cafés, guesthouses, and tech startups in old traditional homes. What were once seen as disadvantages are now being viewed as strengths. Isolation brings peace and focus. Clean air and pure water are prized in a polluted world. Distinct seasons provide a rich, authentic quality of life. The Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale is a renowned example of this reinvention. This large contemporary art festival disperses hundreds of artworks across a vast rural area in Niigata, attracting international tourists and revitalizing the region by transforming abandoned schools and farmhouses into galleries, fostering dialogue between contemporary art and the traditional landscape. There is also renewed appreciation for the food culture. High-end restaurants in Tokyo and abroad highly value the uniquely naturally sweetened vegetables from the ‘yukimuro,’ and Niigata’s premium sake enjoys a global following. People are beginning to understand that the Yukiguni lifestyle is not about being ‘behind the times’; it embodies timeless wisdom that offers valuable lessons for today’s fast-paced, disconnected world.

So the next time you see an epic photo of Japanese powder, look a little deeper. See beyond the peaceful, beautiful surface. Recognize the centuries of struggle, the backbreaking work of yukikaki, and the quiet resilience etched into the faces of those who call this place home. Understand that the incredible food you eat and exquisite sake you drink are not merely products; they are stories of survival, ingenuity, and a profound partnership with a formidable climate. Yukiguni is not a static, picturesque postcard—it is a living, breathing testament to how harsh conditions can forge the strongest communities, the most patient souls, and a culture rich in depth and beauty. It reminds us that true strength isn’t about conquering nature, but learning to dance with it, even when it leads with a heavy, frozen step. And that, low-key, is one of the most authentically Japanese things you can ever hope to understand. IYKYK.