Yo, what’s the move? It’s Shun Ogawa, and today we’re ditching the main roads. We’re going off-grid, deep into the heart of Japan’s electric soul. Forget the skyscrapers and the sterile, high-tech future you see in magazines. We’re hunting for a different kind of future, one that’s tangled up in the past. We’re diving headfirst into the world of yokocho—the side alleys that are the real lifeblood of Japanese cities. This ain’t your average tourist trap guide, for real. This is for those who crave the unfiltered, the gritty, the authentic. We’re talking about spots where the Showa era—that wild, post-war period of rebuilding and dreaming big—crashes head-on into a cyberpunk aesthetic. Think neon bleeding onto wet asphalt, smoke billowing from a thousand tiny grills, and ghosts of the past sipping sake next to you. It’s a vibe that’s both nostalgic and futuristic, a place where time gets a little… weird. These alleys are more than just places to eat and drink; they’re living, breathing historical documents, pulsing with stories. They’re the last stand of a certain kind of Japan, and honestly, they’re lit. So, grab a seat, ’cause we’re about to spill the tea on the most iconic yokocho that are serving major cyberpunk-meets-Showa energy. It’s a whole mood, a trip back in time and into the future, all at once. Let’s get it.

If you’re feeling this gritty, nostalgic energy, you might also vibe with the authentic, retro atmosphere of Japan’s classic shōtengai.

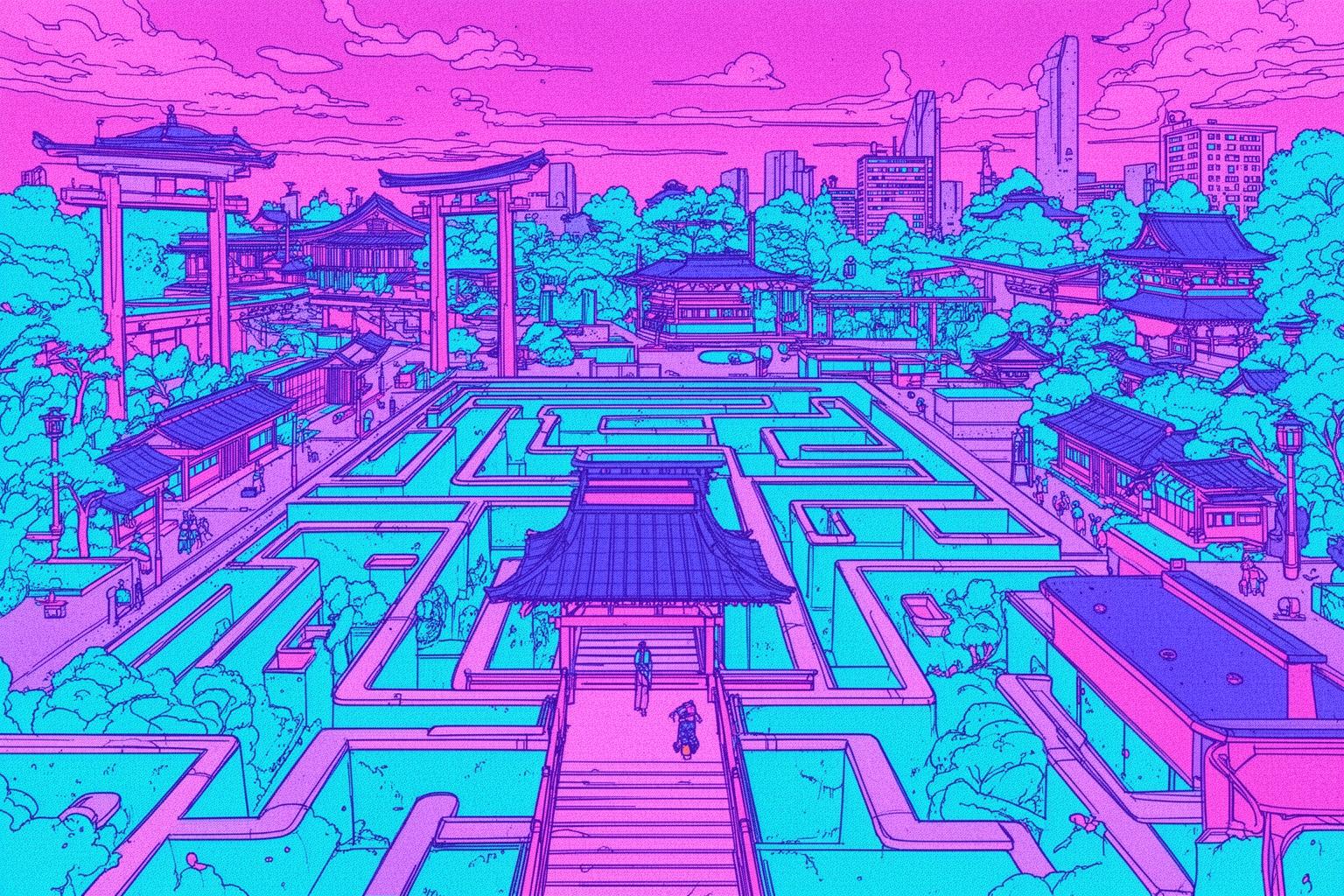

Shinjuku Golden Gai: The OG Labyrinth

Where It All Began

Alright, let’s begin with the legend itself: Shinjuku Golden Gai. If yokocho culture had a hall of fame, this spot would be the centerpiece, no joke. Tucked away in a corner of the otherwise dazzlingly modern Shinjuku, Golden Gai hits like a system shock. You turn a corner, and suddenly, the 21st century fades away. You’re transported to a movie set, a pocket dimension frozen in time around 1965. This tiny patch, just a few blocks, houses over 200 tiny bars, some so small they only fit four or five people at once. The buildings are ramshackle, two-story wooden structures that have somehow weathered fires, earthquakes, and relentless urban development. History is carved into every beam and nail here.

Golden Gai emerged from the ruins of post-war black markets. Its current shape took form in the late 1950s and it became a well-known hub for Tokyo’s counterculture scene. We’re talking about writers, artists, filmmakers, musicians, and actors—a kind of Greenwich Village for Tokyo, but far more intimate and intense. Figures like Yukio Mishima and Akira Kurosawa were known to gather here, debating art and life over cheap drinks. That creative, slightly chaotic energy still lingers. Walking through its six narrow alleyways, you sense the ghosts of those intellectual duels and artistic breakthroughs. The atmosphere is thick with nostalgia and rebellion.

The Vibe Check: Showa Soul, Cyberpunk Shell

So where does the cyberpunk vibe come in? It’s all in the visuals. The alleys are so narrow you can almost touch both sides at once. Above you, a tangled web of electrical wires and pipes cuts across the sky, blotting out the stars—the very essence of urban density. At night, the area glows softly with the light of numerous paper lanterns and the occasional flickering neon sign advertising a bar you can barely glimpse inside. Each sign stands like a beacon, a portal to another world. When it rains, the scene transforms. The narrow lanes turn into reflective canvases, with bar lights bleeding into shimmering pools on the ground. It feels like walking through a real-life Blade Runner set. The only thing missing is a flying car.

The bars themselves are the beating heart of Golden Gai. Each is its own universe, shaped by its owner or “master.” Some bars follow themes—punk rock, old movie posters, literary salons—while others are simple wooden counters polished smooth by decades of elbows and spilled drinks. Climbing the insanely steep, narrow stairs to a second-floor bar feels like ascending into a secret hideout. This vertical layering and density, this sensation of hidden realms stacked vertically, is quintessentially cyberpunk. It captures the spirit of high-tech, low-life, if not in technology then in vibe. Just a block away rise the towering, gleaming skyscrapers of Shinjuku, and here you are in this gritty, human-scale maze. The contrast is everything.

How to Navigate Golden Gai

A quick tip for newcomers: Golden Gai can feel a bit intimidating at first. Many bars charge a cover fee or otōshi, a small mandatory appetizer. This helps screen casual onlookers and keeps the atmosphere intimate for regulars. Some bars are even regulars-only, so don’t take offense if you see a sign saying so. The best approach is to stroll around, soak in the vibe, and find a spot that feels welcoming. Peek through the tiny windows. If you see an open seat and the mood feels right, open the door and ask, “Ii desu ka?” (Is it okay?). Once inside, you’re not just a customer—you’re a temporary member of a small, fleeting community. Chat with the master, strike up a conversation with the person next to you. That’s where the magic happens. Just remember to be discreet with photos; many bars forbid photography to protect patrons’ privacy. Show respect, and Golden Gai will give you a night you’ll remember forever.

Omoide Yokocho: Grilling in the Shadow of the Future

A Trip Down Memory Lane (Literally)

Let’s head over to the west side of Shinjuku Station to another iconic spot: Omoide Yokocho. The name literally means “Memory Lane,” and it truly lives up to that reputation. This place is a full-on sensory overload—in the best way imaginable. While Golden Gai offers intimate, quiet drinking nooks, Omoide Yokocho is a lively, smoke-filled celebration of affordable, delicious food and drinks. Its other, more notorious nickname is “Piss Alley,” a remnant from its post-war days when plumbing was, shall we say, not a priority. Don’t worry, proper facilities are in place now, but the nickname stuck, adding to its gritty, no-frills charm.

Like Golden Gai, Omoide Yokocho originated from the black markets that emerged around major train stations after World War II. It was a place to find a hot meal and a stiff drink when resources were scarce. Its specialty, then and now, is yakitori (grilled chicken skewers) and motsuyaki (grilled offal). The entire alley is constantly enveloped in the fragrant cloud of grilling meat—a smell that hits you from a block away and draws you in. This spot is the spiritual home of the salaryman, the Japanese office worker, who comes here after a long day to unwind, shed the corporate facade, and reconnect over skewers and beer.

The Aesthetic: Industrial Grit and Human Warmth

The cyberpunk vibe here is less about neon lights and more about the raw, industrial texture of the space. The alley is incredibly narrow—a tight corridor lined with tiny open-fronted stalls. You sit on simple wooden stools or crates, your back nearly against the wall, while a steady flow of people moves past. The kitchens are right before you, a chaotic dance of flames, smoke, and steel. The chefs, often grizzled grill veterans, operate with practiced, almost robotic precision, flipping skewers and calling out orders. Above, the tangle of wires and ducts resembles that of Golden Gai, but here it feels greasier, more utilitarian. Steam and smoke vent directly into the narrow space, creating a hazy fog that softens the harsh fluorescent lighting.

The contrast is what makes it so captivating. You’re seated in this rustic, almost medieval-looking market, yet you’re literally in the shadow of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building and the futuristic skyscrapers of West Shinjuku. It’s a glitch in the urban matrix. The constant rumble of trains from the world’s busiest station forms the soundtrack, a reminder of relentless modernity just steps away. Inside the alley, however, it’s all about the primal, communal experience of eating fire-cooked meat. It’s a low-life paradise in a high-tech world—a place where people connect on the most fundamental level.

The Omoide Yokocho Experience

Navigating Omoide Yokocho is simple: find a stall with an empty seat and take it. Most places offer English menus or, at the very least, you can just point at the skewers you want. Be adventurous. Try the hatsu (heart), leba (liver), or shiro (intestines). It’s all part of the experience. The food is cooked to perfection, seasoned simply with salt (shio) or a sweet soy glaze (tare). Paired with a frosty mug of beer or a cheap glass of shochu, it makes for a perfect meal. This isn’t fine dining; it’s soul food. It’s about the noise, the smoke, and the camaraderie of sharing a tiny space with strangers. You’ll leave smelling like a delicious barbecue—a badge of honor that signals you’ve experienced one of Tokyo’s most authentic culinary rituals.

Harmonica Yokocho: The Kichijoji Maze

A Different Beat in West Tokyo

Let’s leave the frenzy of central Tokyo behind and head west to Kichijoji, a neighborhood frequently ranked among the most desirable places to live in the city. It exudes a more relaxed, bohemian atmosphere, and right beside the station is Harmonica Yokocho. This alleyway complex stands apart from the large-scale establishments in Shinjuku. Its name derives from the way the rows of tiny shops and eateries resemble the reeds of a harmonica. During the day, it functions as a bustling market, with fishmongers, butchers, and florists busy at work. But when night falls, the shutters rise on dozens of small bars and restaurants, and the whole place is transformed.

Its roots trace back, as you might expect, to a post-war black market. The maze-like design is a direct result of its spontaneous, unplanned development. It consists of five incredibly narrow alleys, and getting lost is part of the charm. One moment you’re in a lane that feels historically Japanese, and the next you turn a corner into a standing-only tapas bar that might as well be in Barcelona. This blend of old and new, local and international, is what gives Harmonica Yokocho its distinctive character.

The Vibe: Bohemian Rhapsody

Harmonica Yokocho’s cyberpunk vibe is subtle, more focused on spatial experience. The narrow alleys create a sense of compression, while the open sky above reminds you that you’re still in a city. The lighting is an eclectic mix: glowing red lanterns, bare fluorescent tubes, and chic Edison bulbs from a trendy new wine bar. This combination produces a visually rich and layered atmosphere. You’ll find a traditional taiyaki (fish-shaped cake) stand right next to a craft beer bar featuring sleek, modern design. This ongoing shift in styles is delightfully disorienting, like multiple realities converging in one compact space.

The human presence is essential here. Because the spaces are so small, life spills out into the alleys. People gather around tiny tables, drinks in hand, their conversations echoing through the labyrinth. It’s a fluid and dynamic social scene. You’re not just observing; you’re immersed in the flow. The sounds of sizzling gyoza, clinking glasses, and many different languages blend into a unique urban symphony. It’s a microcosm of modern Tokyo: diverse, chaotic, and vibrantly alive.

What to Eat and Drink

The sheer variety at Harmonica Yokocho is incredible. You can kick off your evening with some of Tokyo’s best gyoza at an iconic spot, then move on to fresh sashimi, yakitori, or even wood-fired pizza, all just steps apart. This culinary diversity makes it an ideal setting for hashigo-zake, or bar-hopping. The idea is to have one drink and one dish at each place before moving on. It’s a fantastic way to sample everything the yokocho offers and experience the distinct atmosphere of each tiny venue. Harmonica Yokocho isn’t about deep historical grit as much as it celebrates the playful, creative energy of modern Kichijoji, all set within a charmingly aging Showa-era backdrop.

Noge Tangaigai, Yokohama: Jazz, Grit, and the Sea

Yokohama’s Hidden Heart

Let’s catch a train and head south to Yokohama, Tokyo’s trendy coastal neighbor. While most visitors flock to the futuristic Minato Mirai 21 waterfront, the true essence of the city lies in the Noge district. And within Noge, the gem is the Tangaigai area, a cluster of yokocho that feels completely untouched by time. The contrast here is striking. You can see the gleaming Landmark Tower, one of Japan’s tallest buildings, in the distance, then step into a world of low wooden buildings, smoky grills, and the soft sounds of jazz drifting from a hidden bar.

Noge’s history is closely tied to Yokohama’s port and the post-war presence of the U.S. military. This gave it a more international and slightly rough-edge vibe compared to Tokyo’s yokocho. It became a hub for black market goods, cheap entertainment, and, most famously, jazz music. Japan’s jazz scene blossomed here, and that heritage remains alive in the many tiny jazz kissa (cafes) and bars still tucked away in these alleys.

A Walk on the Wild Side

The vibe in Noge is raw and genuine, with a hint of the unusual. The alleys are dark, narrow, and winding. The buildings seem to lean on each other for support. Its cyberpunk feel comes from this impression of a forgotten zone, an autonomous enclave existing alongside a hyper-modern city. The visual style is pure Showa grit: peeling paint, rust-marked signs, and a glorious mess of overhead wires. It’s a photographer’s paradise.

What sets Noge apart is its slightly quirky character. You’ll find bars with unusual themes and restaurants serving uncommon dishes. One notorious spot is known for offering a variety of animal meats, a nod to the post-war era when people ate whatever they could find. This isn’t for everyone, but it speaks to the area’s raw, unapologetic history. The real gems, though, are the jazz bars. These tiny, reverent spaces invite you to sip whiskey and listen to classic vinyl on amazing sound systems. They serve as time capsules of a different kind, preserving a subculture that has shaped Noge for decades. The vibe is more melancholic and soulful than the lively yokocho of Tokyo, but no less impactful.

Exploring Noge

Noge is best discovered with an open mind. Just wander. Let the sounds and smells lead you. You’ll meet friendly locals, enjoy cheap and delicious food (especially fresh seafood, thanks to the port nearby), and feel a strong sense of history. It’s a place that hasn’t been overly sanitized for tourists. It’s genuine. The blend of Showa-era architecture, lingering American cultural influence through jazz, and sharp contrast with the shiny city next door makes Noge a fascinating and layered destination. It’s a reminder that even in a country as orderly as Japan, there are still places that stay a little wild.

The Cyber-Showa Aesthetic: A Deeper Look

Decoding the Vibe

We’ve been tossing around the phrase “Cyberpunk-meets-Showa.” Let’s break it down properly. What about these old alleys feels so futuristic and dystopian? It’s a blend of textures, philosophies, and historical layers. It’s not just about appearance; it’s an entire atmosphere.

The Showa era (1926-1989) was a time of profound transformation in Japan. It experienced militarism, devastating war, and then an extraordinary economic revival. The post-war Showa period, particularly from the 1950s to the 1970s, is what we call “Showa Retro.” It was an era defined by grit, resilience, and ambition. Cities were rebuilt at a breakneck speed, often in a chaotic, organic way. There was a community spirit born out of hardship. Yokocho represent this spirit architecturally. They are cramped, practical, human-scaled spaces designed for survival and connection. The wooden counters, simple stools, and paper lanterns—all of this forms part of a nostalgic visual language.

High Tech, Low Life

Now, consider the cyberpunk aesthetic. Classic cyberpunk—from William Gibson’s novels to movies like Blade Runner—depicts a future characterized by stark contrasts: astonishing technological advancements alongside social decay and urban grit. The motto is “high tech, low life.” While a Showa-era yokocho may lack cyborgs or flying cars, it shares the same fundamental aesthetic principles. Think about it: dense, vertical, labyrinthine urban landscapes. The constant presence of technology—not in sleek, clean minimalist form, but as a messy, functional overlay—the tangled web of electrical wires, humming air conditioners attached to crumbling walls, flickering neon signs casting an artificial glow.

The atmosphere is another key connection. Cyberpunk futures are often relentlessly dark, rainy, and lit by artificial light. This perfectly matches the feeling of a yokocho at night, especially in the rain. Steam rising from food stalls and sewer grates creates a hazy, cinematic fog. The narrow alleys provoke a sense of claustrophobia and enclosure, a world within the city itself. It’s a realm of shadows, secrets, and transactions—an ideal backdrop for a noir or cyberpunk narrative. The yokocho exemplifies how the past isn’t erased by the future but instead forms a textured, gritty foundation upon which the future is roughly constructed.

A Symphony of the Senses: It’s More Than Just a Look

The Soundtrack of the Alley

To truly capture the yokocho atmosphere, you need to engage all your senses. It’s a full-body experience. Close your eyes for a moment in the heart of Omoide Yokocho. What do you hear? It’s a symphony. There’s the steady sizzle and pop of meat hitting a hot grill, the rhythmic clack of the chef’s tongs. You catch the low, constant hum of a dozen conversations in Japanese, a language that can sound both percussive and melodic. You’ll hear the hearty laughter of a salaryman who’s had one too many beers, the sharp clink of glasses, the scraping of a stool against the concrete floor. From a nearby bar, a crackly Showa-era pop song might be playing on an old radio. Beneath it all, the distant, rhythmic rumble of a train pulling into the station. It’s a rich, layered soundscape that completely immerses you.

The Air You Breathe

Then there’s the smell. Oh, the smell. It’s the first thing that hits you and the last thing that lingers (your clothes will carry its memory home with you). Each yokocho has its own distinct scent profile. In Omoide Yokocho, it’s the overpoweringly delicious, smoky aroma of grilled chicken and pork, a savory perfume of rendered fat and sweet soy glaze. In Golden Gai, the air is more a mix of old wood, stale cigarette smoke, and the faint, sweet scent of sake. In Harmonica Yokocho, the aromas constantly shift as you wander through the maze—one moment it’s frying gyoza and garlic, the next it’s the briny smell of fresh seafood from a fishmonger. These smells are not mere background; they form part of the story. They are Proustian triggers that can transport you back to that alley long after you’ve left.

The Taste of History

And, of course, there is the taste. Yokocho food isn’t fancy. It’s honest. It’s fuel. It’s comfort. The taste of a perfectly grilled piece of chicken skin—crispy, salty, slightly charred—is pure, unadulterated pleasure. The taste of motsuni, a slow-cooked stew of offal and vegetables in miso broth, is a taste of warmth, of creating something delicious from humble ingredients. It’s a taste of post-war ingenuity. The sharp, clean taste of cold sake cuts through the richness of the grilled food. These flavors are deeply rooted in Japanese culinary history. They’re simple, yet perfected. Eating in a yokocho is a direct communion with the culinary soul of urban Japan.

The Yokocho Code: How to Vibe Like a Local

Reading the Room

Alright, so you’re ready to jump in. But yokocho come with their own unwritten rules and social etiquette. Figuring these out is crucial to having an awesome experience and not just looking like a clueless tourist. The most important rule is to stay observant. These spots are small and intimate, so your energy influences everyone else’s. Take a moment to gauge the atmosphere before entering. Is it quiet and subdued? Or loud and lively? Match the mood accordingly.

Securing a seat is the first challenge. If you spot an empty spot, it’s polite to make eye contact with the master and ask if you can sit there. A simple “Suwatte mo ii desu ka?” (May I sit?) goes a long way. Don’t just plop down. In many of these tiny places, the master is more than just a bartender; they are the host and the curator of your evening’s experience. Respect their space.

The Art of Ordering

Once seated, the first order of business is to order a drink. It’s generally expected that you order a drink before looking at the food menu. This keeps things running smoothly. If you’re unsure what to choose, a draft beer (nama biiru) is always a safe option. Don’t be surprised if a small dish arrives that you didn’t order. This is the otōshi, or table charge/appetizer mentioned earlier, a common practice in many izakaya and yokocho bars. Just accept it gracefully; it’s part of the experience.

When ordering food, don’t hesitate. If there’s no English menu, pointing is perfectly fine. Or try learning a few key phrases. “Kore, kudasai” (This one, please) while pointing is your trusty go-to. “Osusume wa nan desu ka?” (What do you recommend?) is a great way to connect with the master and try their specialty. Order a few dishes at a time rather than all at once. Yokocho dining is a marathon, not a sprint.

Social Dynamics

The charm of a yokocho lies in its potential for spontaneous connections. Sitting shoulder-to-shoulder with strangers sparks natural conversations. If someone next to you starts chatting, go with the flow. You might meet some fascinating people. But don’t force it. If others seem lost in their own world, respect that. The golden rule is to be a considerate neighbor. Don’t take up too much space, avoid being loud, and don’t overstay your welcome, especially if others are waiting for seats. Most yokocho regulars have a few drinks and some food before moving on to the next spot. This culture of hashigo-zake (bar hopping) keeps the energy vibrant and allows more people to enjoy the limited space. When it’s time to settle the bill, just signal the master by saying (o-kaikei, onegaishimasu). Tipping isn’t customary in Japan. A simple “Gochisousama deshita” (Thank you for the meal) is the best way to show your gratitude.