You ever scroll through your feed, see a picture of some wild-looking building in Japan, and just think, what is going on here? It’s not the traditional shrines or the neon-drenched Blade Runner cityscapes you expect. It’s something else. Something… concrete. Brutal, yet somehow intricate. It’s giving giant Jenga tower, it’s giving sci-fi movie set from the ‘70s, it’s giving… a vibe you can’t quite put your finger on. You see these buildings, often with parts that look like they’re just clipped on, stacked like Lego bricks, or branching out like a colossal concrete tree. And the question that hits different is: why? Why does Japan have these retro-futuristic, almost alien-looking structures just chilling in the middle of its cities? Is it just an aesthetic choice, or is there a deeper story? Bet. There’s a whole saga behind it. What you’re looking at isn’t just random architectural flexing; it’s the physical ghost of a hyper-optimistic, slightly chaotic, and uniquely Japanese dream for the future. It’s called Metabolism, and real talk, it’s one of the most fascinating keys to understanding modern Japan’s psyche. It’s a story about a nation hitting reset, staring into the abyss of its own destruction, and deciding to build not just for the present, but for a future that was constantly changing, growing, and regenerating. It was a vision of cities as living, breathing organisms. So, let’s get into it, let’s unpack why these concrete behemoths exist and what they tell us about Japan’s non-stop cycle of tearing down and building up. It’s a deep cut, but once you get it, the entire Japanese urban landscape starts to make a different kind of sense.

To truly grasp this aesthetic, it’s essential to understand the underlying philosophy of Japanese minimalism and its relationship with concrete.

The Vibe Check: What’s Up With Japan’s Sci-Fi Concrete Jungles?

So, imagine this: you’re strolling through Ginza or Shimbashi in Tokyo, or perhaps a smaller city, and you spot it. A tower that resembles less an office building and more a support column from a space station. It has these small boxes jutting out or looks like a massive trunk with smaller structures clinging to it desperately. The material is almost always raw, exposed concrete—what architects call béton brut. It lacks the sleek glass-and-steel finish of modern skyscrapers. Instead, it possesses a heavy, monumental, almost monolithic presence. It feels both ancient and futuristic, a paradox sculpted in concrete. This is the hallmark of Metabolism. Your initial response might be confusion. Is it beautiful? Is it ugly? Is it even complete? The aesthetic is challenging, subtly aggressive, and completely unapologetic. It doesn’t blend in; it stands out and demands your attention. You see these buildings in vintage sci-fi anime, in the backdrop of gritty yakuza films, and in the grids of photographers fascinated by brutalism. It’s an entire vibe. The confusion is understandable because Metabolism wasn’t merely about creating pretty structures. It was a bold statement. It was a collective of young, ambitious architects looking at the chaotic, sprawling aftermath of post-war Tokyo and declaring, “We can do better. We can design a future that isn’t static but alive.” These buildings are the tangible remains of that ambition. They’re not just unusual towers; they’re philosophical debates made from rebar and concrete. They ask a question: What if a city wasn’t a fixed, finished entity, but a process? What if it could grow, contract, and adapt like a living organism? That’s the essence of the Metabolist outlook. It invites you to see the city not as a noun, but as a verb—an ongoing act of creation and destruction. And to grasp why this idea took such deep root in Japan, you have to rewind to a time when the entire country was a blank canvas.

Post-War Scramble: Building a New Japan on Level Zero

To truly understand Metabolism, you can’t simply begin with the blueprints. You have to start with the rubble. In 1945, much of Japan was literally wiped away. Major cities like Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya were firebombed into vast, flat expanses of ash and scorched earth. The physical devastation was total, but the psychological impact was even more profound. An entire worldview had collapsed. The nation confronted a total identity crisis—a hard reset on an almost unfathomable scale. This was the foundation from which Metabolism emerged. It wasn’t born in a peaceful university seminar; it was forged in the crucible of national trauma and the urgent energy of rebuilding. For the generation of architects who matured in the 1950s, the world wasn’t a preservation project; it was something to be constructed anew. They witnessed impermanence firsthand. Their childhood homes, schools, and cities disappeared almost overnight. This shaped a deep awareness within them: nothing lasts forever. This concept, known in Japanese as mujō (無常), has deep roots in Buddhist thought, but for this generation, it wasn’t an abstract religious notion—it was their lived experience. So, when the time came to rebuild, they weren’t interested in replicating the past because the past was gone. They aimed to create a future capable of withstanding change, one that wouldn’t collapse with the next major shock—whether earthquake, war, or population surge. The post-war economic boom fueled this momentum. Japan was rebuilding at breakneck speed, transforming from a defeated, agrarian nation into an industrial and technological powerhouse. Cities swelled with new inhabitants, industries, and challenges. Overcrowding, pollution, and chaotic urban expansion became everyday issues. The traditional city-planning models were failing spectacularly. This was the perfect storm for a revolutionary new way of thinking.

From Ashes to Megastructures: The Birth of a Movement

Metabolism’s official debut was at the 1960 World Design Conference in Tokyo—a major event showcasing Japan’s return to the global stage culturally, intellectually, and economically. A group of young Japanese architects, critics, and designers seized the opportunity. Led by figures like Kisho Kurokawa, Kiyonori Kikutake, Fumihiko Maki, and critic Noboru Kawazoe, with Kenzo Tange as a kind of spiritual mentor, they published a manifesto titled “Metabolism: The Proposals for New Urbanism.” The name itself was a statement. They drew the term “Metabolism” from biology, describing how life sustains itself through material and energy exchange and renewal. This was their core idea: cities and buildings should act like living organisms—dynamic systems capable of growth, change, and regeneration rather than static monuments. The manifesto was packed with radical, mind-bending diagrams and essays. They proposed cities floating on oceans, towers attached to central cores like leaves on a tree, and urban landscapes that could be reconfigured on demand. It was bold, utopian, and profoundly strange—and it perfectly captured the spirit of a nation obsessed with the future. They weren’t merely designing buildings; they were inventing new ways of living for a new era of humanity. They foresaw the traditional family dissolving into the individual urban nomad and anticipated a world defined by mass mobility and technological upheaval. Their architecture sought to provide a structure for this uncertain, thrilling, yet daunting new world.

The “Metabolism” Glow-Up: More Than Just Architecture

What made Metabolism distinctly Japanese was how it combined futuristic sci-fi vision with ancient traditions. On the surface, it seemed like a full break from the past. But if you look deeper, the connections are clear. It was a cultural remix. The most famous example is the shikinen sengu ritual, the Ise Grand Shrine’s 20-year reconstruction cycle. For over a thousand years, Japan’s most sacred Shinto shrine has been systematically dismantled and rebuilt identically on an adjacent site. This practice embodies a distinctly Japanese vision of permanence—not in the physical material, which is transient and decays, but in the form, technique, and process of renewal. The spirit and skills are preserved through continuous rebirth of the structure. The Metabolists, in a sense, secularized this concept and applied it to the modern city. They argued that a building’s true longevity lay not in an unchanging structure but in its capacity for renewal. The permanent component—the “megastructure”—was like the shrine’s sacred site and form. The temporary components—the “capsules” or “modules”—were like wooden beams destined to be replaced over time. This blend of old and new is a classic Japanese approach. It explains how a thousand-year-old temple can coexist alongside a futuristic skyscraper. The culture doesn’t force a choice between tradition and modernity; instead, it layers them, allowing each to inform the other. Metabolism was the architectural embodiment of this cultural instinct—a way to build a hyper-modern future without erasing the philosophical DNA of the past.

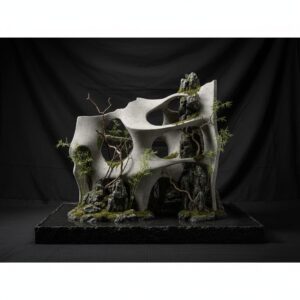

Deconstructing the Core: The Metabolist Playbook

Alright, so we’ve got the historical background and philosophy set. But what does a Metabolist building actually look like, and how is it supposed to function theoretically? The movement wasn’t uniform; different architects had their own interpretations. Still, there were a few central concepts—a shared framework—that defined the style. It focused on distinguishing the long-term from the short-term, the permanent from the temporary, the collective from the individual. This approach wasn’t merely aesthetic; it was a deeply practical, though ultimately flawed, method for addressing the challenges of the modern city. The visual language born from these ideas—the branching cores, plug-in pods, massive skeletal frames—is what gives Metabolism its unmistakable and enduring sci-fi character.

The Megastructure Mainframe

At the very core of Metabolist thought is the “megastructure.” This is the large, permanent element. Think of it as the skeleton or central nervous system of a city or building. It’s the massive, unchanging core housing all essential infrastructure: transportation like highways and subways, energy lines, water pipes, and communication networks. For a single building, this would be the central tower or structural frame. Kenzo Tange’s “A Plan for Tokyo 1960” stands as the most epic, almost mythical, example. Faced with Tokyo’s explosive growth, he didn’t just propose new buildings; he envisioned a whole new city axis formed by colossal bridges spanning Tokyo Bay. This linear megastructure was to become a new civic spine for the city. Designed to last centuries, it was a monumental piece of infrastructure. All other parts of the city—offices, residences, shops—would be plugged into this mainframe. The idea was to create a clear hierarchy: individuals could modify their immediate surroundings, but everyone remained connected to and supported by this vast, stable collective infrastructure. It was a powerfully optimistic vision: a way to create order from chaos without relying on rigid, top-down planning. The megastructure set the rules, but within that framework, the city could grow and evolve organically. This concept is echoed in countless sci-fi narratives, from Paolo Soleri’s arcologies to the urban landscapes of Ghost in the Shell. Yet, the Metabolists aimed to realize it for real.

Capsule Life: Plug-and-Play Living Pods

If the megastructure forms the skeleton, the “capsules” are its living cells. This is the most famous and visually iconic element of Metabolism, the feature that truly shouts future. The idea was straightforward but revolutionary: individual living spaces, offices, or hotel rooms would be prefabricated as self-contained pods, or capsules. These capsules would then be attached to the megastructure. The key concept here is replaceability. The megastructure is permanent, but the capsules are temporary. They were designed with a shorter lifespan in mind—about 25 to 30 years. When a capsule grew outdated, deteriorated, or its occupant desired an upgrade, you could theoretically unplug the old one and plug in a new one without disturbing the main structure or neighbors. This represented the ultimate flexible, adaptable society. Your home wasn’t a fixed asset on land; it was a consumer product, an appliance you could swap like a smartphone. This vision suited the notion of the future “Homo movens,” the constantly moving individual unburdened by possessions or permanence. It was architecture as hardware, with capsules as swappable software modules. This plug-and-play philosophy directly responded to Japan’s burgeoning throwaway consumer culture of the booming 1960s. It also offered a clever solution to urban density: building vertically and enabling continual renewal to house an ever-growing population within a perpetually modernizing city.

The Nakagin Capsule Tower Saga: An Icon’s Rise and Fall

You can’t discuss capsules without mentioning the undisputed GOAT, the emblematic symbol of Metabolism: Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower. Completed in 1972 in Ginza, Tokyo, it represented the purest, most complete realization of the Metabolist vision ever constructed. The relatively small building consisted of two interconnected concrete cores to which 140 prefabricated capsules were bolted on with high-tension fasteners. Each capsule was a tiny, self-contained world—a 10-square-meter micro-apartment designed for a single salaryman or artist. It came fully furnished: a bed, a compact bathroom unit (similar to those now common in Japanese business hotels), a fold-out desk, and cutting-edge electronics of the era, like a reel-to-reel tape player and a Sony television. It quickly became a global sensation. It appeared otherworldly and graced the covers of architecture magazines worldwide, symbolizing Japan’s futuristic ambition. But here’s where dream meets reality—the “real vs. expectation” moment. The plug-and-play concept never materialized. Not a single capsule was ever replaced. Why? First, the process turned out to be far more complex and costly than anticipated. Swapping one capsule couldn’t happen without impacting those above and below; it required a massive crane and a coordinated effort that residents never agreed on or could afford. Over time, the tower degraded. The once-sleek white capsules became stained and rusty. Water leaks became persistent. The originally advanced heating and cooling systems ceased to function. The building gradually shifted from a utopian ideal to a dystopian ruin—a vertical slum in one of the world’s priciest neighborhoods. For decades, a struggle ensued between residents advocating demolition and passionate preservationists (along with some residents) seeking to protect it as a cultural landmark. They claimed it was a masterpiece, a unique piece of architectural history. Yet maintenance costs soared, and the building failed to meet modern earthquake standards. Ultimately, reality prevailed. In April 2022, demolition of the Nakagin Capsule Tower commenced. It was a heartbreaking moment for architecture enthusiasts but also a powerful, if bittersweet, closing chapter. The building designed for change proved unable to adapt and was consumed by the very cycle of destruction and renewal it symbolized. The saga perfectly embodies Metabolism itself: a brilliant, beautiful idea that may have been too idealistic to endure in the real world.

The Legacy on the Streets: Where to Catch the Metabolist Wave Today

Even though its most iconic structure has been lost, the spirit of Metabolism still lingers in the Japanese cityscape. The movement itself was brief, mostly fading out by the late 1970s, but its impact was immense, with many key examples still standing, allowing you to experience its vibe firsthand. These surviving buildings act as architectural time capsules, providing a direct portal back to an era of boundless optimism and radical experimentation. While they might not have fully realized the “plug-and-play” concept, they remain powerful testaments to the movement’s core ideas. Observing them, you can still sense the energy and boldness of the architects who dared to envision an entirely new kind of future.

Kenzo Tange’s Concrete Kingdom

Kenzo Tange was the master, the sensei of the Metabolist generation. Though he was slightly older and never formally part of the group, his work during this period embodies pure Metabolist spirit and form. He truly mastered the art of the megastructure. His buildings are massive, commanding, and deeply sculptural. A prime example is the Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center in Ginza, Tokyo (not to be confused with the one in Shizuoka city). It’s a beast—a single, giant cylindrical core serving as the megastructure, containing elevators, stairs, and utilities. Clustered around this core, arranged seemingly at random, are the glass-walled office modules—the “capsules.” The design directly expresses function: the central core is the permanent infrastructure, while the office spaces are changeable units that could, in theory, be added or removed as the company’s needs evolved. It’s like a tree trunk with offices branching off. Another masterpiece is the Yamanashi Press and Broadcasting Center in Kofu. Here, Tange expanded the concept further. Instead of one core, there are sixteen cylindrical shafts, creating a forest of concrete towers. The office spaces are connected between these towers, leaving intentional gaps and voids in the structure. Tange himself said these empty spaces were meant for future expansion. The building was designed to be eternally unfinished, a living structure capable of growing and filling its own gaps over time. It’s a powerful statement about growth and potential. Then there’s the Fuji TV Headquarters in Odaiba, Tokyo, a much later work from the 1990s. While technically post-Metabolist, its DNA is unmistakable. It’s a massive megastructure, a gigantic metal lattice housing office and studio spaces. The most striking feature is the huge titanium-clad sphere that seems to float in the middle of the structure. Playful and futuristic, it clearly nods to the Metabolist love of geometric forms and structural exhibitionism. Tange’s work demonstrates how Metabolism’s core ideas—the separation of core and unit, the capacity for growth—could be adapted and refined over time.

Beyond the OGs: Metabolism’s Ghost in the Machine

Metabolism’s influence didn’t end with the original members. Its ideas permeated Japanese architecture and pop culture. If you know where to look, you can see its ghost in the machine everywhere. Many later buildings, though not strictly Metabolist, explore modularity, flexibility, and the expression of structural systems. The stacked, blocky forms and intricate silhouettes of many modern Japanese buildings owe a debt to Metabolist experiments. Yet perhaps the movement’s most lasting legacy lies in the realm of imagination. The visual language of Metabolism—dense, layered verticality, capsule pods, hulking megastructures—became the default aesthetic of futuristic cities in countless manga and anime. Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira is the ultimate example. The sprawling, chaotic, and perpetually under-construction Neo-Tokyo is a direct descendant of Tange’s 1960 plan for Tokyo Bay. The city itself becomes a character, a complex, almost cancerous organism of concrete and steel, endlessly destroying and rebuilding itself. The same applies to Masamune Shirow’s Ghost in the Shell. The cityscapes of New Port City, with their dizzying verticality and fusion of high-tech and urban decay, are pure Metabolist nightmares and dreams. Here, Metabolism truly succeeded. The buildings themselves may have faced practical challenges in maintenance and cost, but the idea of Metabolism—the city as a living, evolving, and often overwhelming system—perfectly captured the anxieties and fascinations of modern urban life. It provided the visual vocabulary for a future that was both thrilling and terrifying. In that sense, the movement never really died. It simply… metabolized. It faded from practical construction and was reborn in science fiction, where its utopian ideals could thrive, unbounded by budgets or gravity.

The Reality Check: Why Didn’t We All End Up in Capsules?

If the ideas were so powerful and the vision so compelling, why aren’t our cities today floating on the ocean or made up of plug-in pods? Why did Metabolism as a practical architectural movement eventually fade away? The answer lies in the classic clash between a radical dream and harsh reality. Metabolism’s decline was not due to a single failure but rather a mix of economic, social, and material factors. It was a movement perfectly aligned with the soaring optimism of the 1960s, yet it struggled to adjust to the more cynical and economically unstable decades that followed.

The Dream vs. The Budget

The simplest reason for Metabolism’s decline was financial. Constructing these complex, unconventional structures was extraordinarily expensive. Building massive concrete cores, engineering systems for attaching and detaching modules, and custom-fabricating hundreds of capsules cost far more than traditional methods. The post-war economic boom made such ambitious projects feasible, but when the 1973 oil crisis struck, it all came to a halt. Japan’s economy slowed, and the appetite for costly, experimental public works and private developments vanished. Maintenance was another major issue. As the Nakagin Capsule Tower demonstrated, caring for these unique structures was a logistical and financial challenge. You couldn’t simply call a regular plumber to fix a leak in a capsule suspended 10 stories above ground. The bespoke systems required specialized attention that was often unavailable or prohibitively expensive. The dream of easy, inexpensive replaceability proved to be a fantasy. In the end, the sheer pragmatism of conventional construction—proven, cheaper, and easier to maintain—prevailed. The future was meant to be modular, but instead it was driven by budgets and spreadsheets.

A Society in Flux: The Human Element

Metabolism was also based on specific assumptions about how society would evolve, many of which did not come to pass. The architects imagined a future populated by highly individualistic urban nomads—the Homo movens. The small, isolated capsules of the Nakagin Tower were designed for this kind of person: a bachelor salaryman using his apartment mainly for sleeping. However, this societal vision clashed with Japanese culture’s strong emphasis on family and community. Although the nuclear family was indeed changing, living in complete isolation in a tiny pod lacked the broad appeal the architects hoped for. People still desired space, community, and a connection to the ground. The Metabolist vision was a very masculine one, crafted by men for a particular kind of man. It didn’t address families, children, or the elderly much. Moreover, the idea of a “disposable” home conflicted with the growing aspiration for home ownership, which became central to the Japanese dream during the economic boom. People wanted a permanent asset, a piece of land and a house to call their own, not a temporary appliance. The Metabolists designed for a culture of renters in a society increasingly enamored with owning property.

The Concrete Paradox: Built to Change, Fated to Decay

There’s a deep, almost poetic irony in Metabolism’s choice of materials. The movement’s signature material was exposed concrete, chosen because it was inexpensive, malleable, and could be shaped into the massive, sculptural forms envisioned. It felt honest and powerful. Yet concrete is also heavy, permanent, and prone to decay. This created a fundamental paradox. The architects used a monumental, enduring material to express a philosophy of lightness, impermanence, and change. The result is visible today in the surviving buildings: they don’t appear light and adaptable but heavy, weathered, and aged. Concrete, once a symbol of futuristic strength, has instead become a canvas for time’s effects. Rain stains, cracks, and discoloration convey a kind of decay opposite to the clean, efficient renewal the Metabolists imagined. In a way, these buildings have attained a different kind of Japanese beauty: wabi-sabi, the appreciation of imperfection and transience. They were designed to conquer time through constant renewal but instead have become poignant monuments to time’s inevitable triumph. They are ruins of the future, and perhaps that is their most profound legacy—a somber reminder that even our boldest visions for the future will ultimately be reclaimed by the slow, metabolic processes of nature and time.

So, the next time you see one of these concrete giants in Japan, you’ll understand. You’re not simply looking at an unusual old building; you’re gazing at a fossilized dream. It is physical proof of a distinct moment when Japan, recovering from utter devastation, faced the future with fearless, nearly reckless optimism. Metabolism was an effort to create a living, breathing city that embraced the national obsession with impermanence and renewal. It didn’t quite succeed—the technology wasn’t ready, the funding ran dry, and society evolved differently than the architects predicted. Yet the movement’s failure does not lessen the power of its vision. These buildings remind us that the Japanese cityscape is a layered, living entity—a continual dialogue between a deep, ancient past and an unrelenting rush toward a technology-saturated future. Metabolism was one of the boldest, most fascinating expressions within that conversation, and its echo still resonates today, rumbling through the concrete canyons of Japan’s cities.