Yo, what’s up, world travelers and culture heads! Ami here, checking in from the electric heart of Tokyo. When you think of Japan, maybe your mind conjures up images of serene temples in Kyoto, the organized chaos of Shibuya Crossing, or maybe some next-level streetwear from Harajuku. But let’s peel back a layer, go a little deeper into the cultural psyche. Let’s talk about something huge. Literally. I’m talking about Kaiju. Now, I know what you’re thinking—Godzilla, right? The big G is an icon, a legit global superstar. But he’s just the gateway. The world of Japanese giant monsters is a sprawling, chaotic, and sometimes downright bizarre universe that feels like it was ripped straight from a surrealist painting or, yeah, a child’s most intense fever dream. It’s an art form where imagination isn’t just encouraged; it’s cranked up to eleven until the dials break. This isn’t just about dudes in rubber suits stomping on miniature cities. It’s a canvas for anxieties, a playground for artistic rebellion, and a testament to Japan’s unparalleled ability to create characters that are equal parts terrifying, tragic, and totally unforgettable. We’re about to take a deep dive into the weird end of the pool, exploring the monsters that make you tilt your head and ask, “What were they thinking? And how can I see more?” So grab your popcorn, suspend your disbelief, and get ready to meet the real freaks of the Kaiju scene. The journey into this wild imagination starts right here, in the city that these monsters have famously tried to destroy time and time again.

If you think Kaiju are a testament to Japan’s wild imagination, wait until you see the country’s equally bizarre vending machines.

The Psychedelic Smog Monster: Hedorah’s Eco-Horror Trip

Let’s set the stage. It’s 1971. Japan is experiencing an economic miracle, but it comes at a cost: industrial smog, polluted waters, and a growing environmental unease—this is the reality people are living in. From this anxiety, director Yoshimitsu Banno, a visionary with perhaps a touch of madness, created a monster that perfectly captured this fear. Enter Hedorah, the Smog Monster. This isn’t your typical bipedal dinosaur or mythical creature. Hedorah is something entirely different: a living, breathing mass of industrial sludge given sentience by cosmic rays. It’s less a creature and more a walking, flying, swimming natural disaster—a toxic nightmare that feels all too real.

A Monster of Many Forms

What makes Hedorah a true fever dream is its utter lack of a fixed shape. It’s pure chaos. It begins as a collection of microscopic organisms resembling grotesque tadpoles, merging and growing by feeding on pollution from Japan’s factories. Then it transforms into an amphibious monster that crawls onto land, leaving behind a corrosive sludge trail that melts flesh from bone. Not a fan of that form? No problem. It then shifts into a flying, UFO-shaped creature resembling a moldy pizza, spraying sulfuric acid mist that rusts steel and suffocates everything nearby. Its final form is a towering, vaguely humanoid heap of filth with eerie, blood-red, oval eyes that stare out with an unnerving emptiness. These eyes are nightmare fuel—they convey neither anger nor hunger; they just exist. Vacant. It’s this alien essence, this shapeshifting terror, that makes Hedorah so profoundly unnerving. You can’t reason with it or understand it. It embodies humanity’s garbage coming back to haunt us.

The Film Itself: A Psychedelic Cautionary Tale

The movie, Godzilla vs. Hedorah, is as strange as its monstrous antagonist. Banno didn’t just make a monster movie; he crafted an experimental art film starring Godzilla. The film is filled with trippy, almost hallucinatory sequences. There are bizarre animated segments that depict pollution in a simplistic, almost eerie manner. Psychedelic go-go club scenes feature wild dancers as news of the monster’s destruction unfolds. A haunting song, “Save the Earth,” recurs over scenes of a pristine world, sharply contrasting with the grimy, polluted reality on screen. The film carries a message, but delivers it with the force of a sledgehammer wrapped in tie-dye. Even Godzilla joins in the weirdness. In a moment now legendary for its audacity, Godzilla, after defeating Hedorah, uses his atomic breath to fly backward, pursuing the monster’s last fragment. Yes, you read that correctly—Godzilla flies. This surreal, out-of-character moment perfectly captures the film’s anything-goes spirit. The movie was so unconventional that it famously enraged the executives at Toho, yet its legacy endures. It stands as a time capsule of 1970s counterculture and ecological fear, a cult classic proving that kaiju films can be a platform for bold, even avant-garde, storytelling.

Hedorah’s Lasting Impact

Even today, Hedorah remains distinctive. Amid giant robots and space dragons, the sludge monster ranks as one of Godzilla’s most unique and terrifying foes. It resonates because the fear it represents has never truly vanished. It’s neither an ancient mythical beast nor an alien from the stars; it is a monster of our own making, born from our waste. Traveling through Japan and seeing the ultra-modern, impeccably clean cityscapes of Tokyo or Osaka, it’s striking to recall the era that spawned Hedorah. Visiting industrial areas around Tokyo Bay, such as Kawasaki—once symbols of heavy pollution—you can almost sense the lingering anxiety. Today’s clean, efficient Japan partly arose as a response to the very issues that inspired this cinematic nightmare. Hedorah serves as a reminder that sometimes the most terrifying monsters are those that reflect the darkest parts of ourselves.

The Cyborg Buzzsaw Maniac: Gigan, The Ultimate Alien Weapon

If Hedorah is a monster born from the earth’s pain, then Gigan emerges from a sugar-fueled, comic-book-crazed imagination. There’s absolutely nothing natural about Gigan. Debuting in 1972’s Godzilla vs. Gigan, this creature is pure chaos incarnate, a walking arsenal of destruction crafted by sinister space aliens. But these aren’t just any aliens—they’re giant, intelligent cockroaches from a dying world who inhabit recently deceased human bodies. The premise is already wild, but when they unleash their ultimate weapon, things escalate to sheer madness. Gigan perfectly embodies a creature that could only spring from a kid’s sketchbook. It’s the result of endlessly adding cool features to a monster until it becomes a gloriously nonsensical masterpiece of mayhem.

Deconstructing a Nightmare

Let’s analyze the design, as it’s a brilliant example of bizarre character creation. Gigan is a bipedal monster, vaguely reptilian or avian, but that’s where any familiarity ends. A single, horizontal ruby-red visor serves as its eye, reminiscent of a Cylon from Battlestar Galactica. Its metal beak is already unusual. Instead of hands, its arms end in gigantic, razor-sharp metal hooks or scythes. Its chest isn’t made of flesh and blood; it houses a built-in, vertically rotating buzzsaw. Yes, a buzzsaw—right in its stomach. On top of all that, three large, sail-like fins rise from its back, giving it a spiky, aggressive silhouette. Gigan is a striking blend of cyborg parts and organic tissue, painted in dark greens, blues, and golds. It looks like a space pirate, a killing machine, and a punk rock album cover all at once. There’s no evolutionary logic for a creature to carry a buzzsaw in its abdomen. It exists purely to be awesome and slice through other giant monsters—and it does so with gleeful brutality.

The Chaos of a Tag-Team Battle

Godzilla vs. Gigan is very much a product of its era. With shrinking kaiju film budgets in the early ‘70s, more footage from previous movies was reused. But where funds were limited, creativity soared. The story follows the space cockroaches as they construct a children’s theme park called World Children’s Land, featuring a giant Godzilla tower at its center. Secretly, this tower serves as their invasion base. A ragtag team—a manga artist, his girlfriend, and a couple of hippies—must uncover their scheme. The finale is a massive tag-team battle in an industrial zone. Gigan arrives from space, accompanied by the legendary three-headed dragon King Ghidorah, both under alien control. They clash with Godzilla and his spiky ally, Anguirus, in one of the Showa era’s most brutal fights. Gigan proves a vicious combatant, using his hooks to slash and stab, and his buzzsaw to grind into Godzilla’s flesh, causing geysers of monster blood. This level of violence was shocking for its time. The film is also remembered (or ridiculed) for a scene where Godzilla and Anguirus “talk” using speech bubbles and distorted voices—a goofy, campy, and charming moment that captures the freewheeling spirit of this kaiju era. Gigan isn’t a tragic force of nature; he’s a cosmic bully you eagerly watch get his comeuppance.

The Enduring Punk-Rock Appeal of Gigan

Gigan quickly became a fan favorite. His design is simply too compelling to ignore. He signals a shift from the more naturalistic, animal-like monsters of the ‘50s and ‘60s to the wild, sci-fi-inspired creations of the ‘70s. He’s a weapon, not an animal, battling with cruel cunning that makes him a formidable enemy. Gigan returned in Godzilla vs. Megalon the following year and received a major, supercharged redesign for the Millennium series finale, Godzilla: Final Wars (2004), sporting even more blades and chainsaws. Strolling through Nakano Broadway in Tokyo—a massive multi-story mall and otaku paradise—you’ll find countless Gigan figures in collectors’ shop displays. His silhouette is instantly recognizable. He embodies the untamed creativity that defines this genre. He defies logic, which makes him perfectly fitting in the world of kaiju. He’s the monster you sketched in your notebook during class, brought vividly to life.

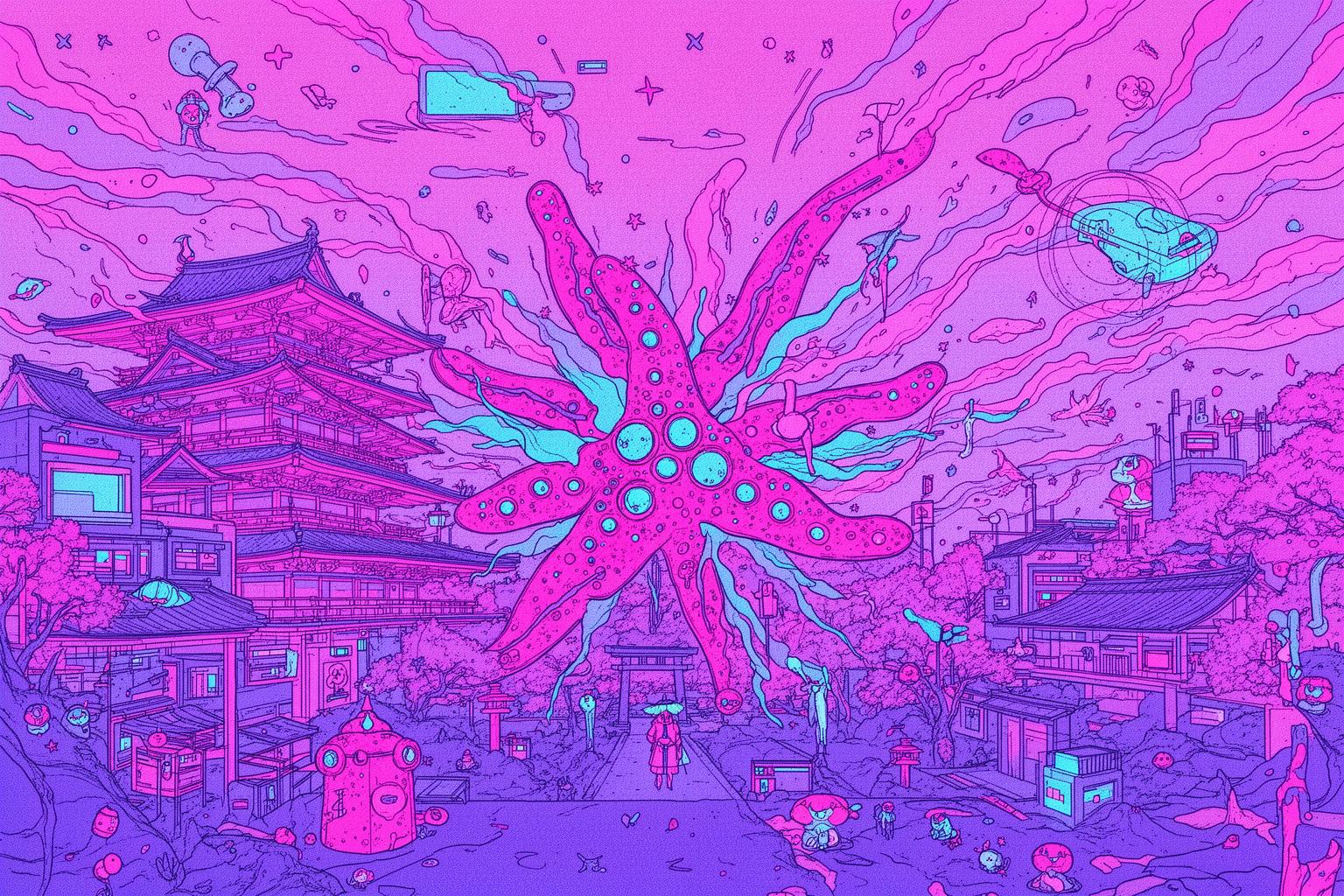

The Toxic Starfish God: Dagarah and 90s Excess

Let’s fast forward a couple of decades. The Showa era, with its campy charm and psychedelic oddities, has given way to the Heisei era. In the 1990s, kaiju films experienced a major resurgence, enhanced by bigger budgets, improved special effects, and a fresh aesthetic. The designs grew more intricate, more detailed, and often, more grotesque. This period gifted us with some amazing reinterpretations of classic monsters, but it also yielded some truly bizarre deep cuts. Case in point: Dagarah, the main antagonist from the 1997 film Rebirth of Mothra II. Whereas Hedorah was a simple, elegant symbol of pollution, Dagarah is its over-the-top, hyper-detailed, 90s-extreme cousin. It’s a monster that feels like it was created by a committee repeatedly insisting, “add more stuff!”

A Creature Caked in Filth

Dagarah is another monster born of pollution, this time from an ancient civilization’s waste. But instead of sludge, Dagarah’s defining trait is Barem. Barem are small, acidic, starfish-like creatures that Dagarah produces from its body—thousands of them. As a result, the monster appears perpetually covered in a swarm of its own toxic offspring. Its base form resembles a four-legged dragon, but it’s so encrusted with spikes, horns, and barnacle-like growths that its original shape is difficult to make out. It can fly, swim, and fire a concentrated beam of Barem and pollution from its mouth. Essentially, it’s a walking, breathing coral reef from the depths of a toxic waste dump. The design is so busy and chaotic that it’s almost overwhelming to behold. It captures a trend in 90s monster design, both in Japan and the West, leaning into complexity and bio-mechanical horror. It’s not just a monster; it’s a complete polluted ecosystem embodied in one creature. This makes it a unique kind of fever dream—not of surreal simplicity, but of suffocating, nightmarish detail.

A Strange Mix of Tones

The Rebirth of Mothra trilogy targeted a younger audience than the mainline Godzilla films of the time. They are bright, colorful adventure stories featuring children as protagonists, alongside Mothra and her tiny priestesses, the Elias. This family-friendly tone makes the arrival of a genuinely disgusting creature like Dagarah all the more striking. Rebirth of Mothra II is essentially a fantasy quest. The kids must find the lost treasure of the ancient Nilai-Kanai civilization to defeat Dagarah. The tale includes magical princesses, underwater pyramids, and a super-cute, fuzzy new version of Mothra called Mothra Leo. Then there’s Dagarah: a monster that spews acid-shooting starfish and resembles a walking biohazard. The climax sees Mothra Leo transform into Aqua Mothra to battle Dagarah underwater, inside the ancient pyramid. It’s a visually spectacular sequence, bursting with dazzling energy beams and explosions, yet fundamentally bizarre. You have this epic, high-fantasy showdown with a creature that is literally a mass of toxic sea debris. It’s a clash of aesthetics that feels uniquely… well, 90s. The film aspires to be a magical adventure akin to something from Studio Ghibli but also wants a gnarly monster that will look cool as a toy. The result is a film that is tonally all over the place, but in an intriguing way.

The Lost World of Nilai-Kanai

The film’s setting draws heavily on the mythology and aesthetics of the Ryukyu Kingdom, the historical culture of Japan’s southernmost islands, including Okinawa. The concept of a highly advanced, ancient civilization lost beneath the waves nods directly to Atlantis legends, but with a distinctively Japanese twist. Visiting Okinawa, one is struck by the vibrant, unique culture and the stunning beauty of its turquoise waters and coral reefs. The film takes this idyllic paradise and introduces a monster that stands as the antithesis of all that beauty—a creature that corrupts and destroys the ocean. It conveys a powerful, if somewhat heavy-handed, environmental message. Dagarah embodies a very specific nightmare: the fear that modern pollution will desecrate something ancient, beautiful, and sacred. While the movie may not be widely regarded as a classic, its monster serves as a perfect example of how the kaiju genre continually evolves, absorbing new aesthetic trends and anxieties with each passing era, even if the results can be a bit… much.

The Four-Legged Apocalypse: Desghidorah, The Planet Eater

King Ghidorah: the three-headed, two-tailed golden dragon from space. As Godzilla’s arch-nemesis, he reigns as the undisputed king of kaiju villains. His design is legendary—a flawless fusion of Eastern dragon mythology and science fiction horror. But how do you create a monster that honors this legacy while also introducing something fresh and strange? In 1996, Toho answered that question with Desghidorah in the first film of the Rebirth of Mothra trilogy. They took the essence of Ghidorah, stripped away its majestic elegance, and replaced it with raw, demonic brutality. Desghidorah is more than just another Ghidorah; it is a primal force of destruction that seems to emerge from a darker, entirely different mythology.

Reimagining a Classic Evil

Though it shares the “Ghidorah” name and multiple heads, Desghidorah is a drastic departure. First, it is a quadruped, walking on four powerful legs that give it a more bestial, animalistic stance compared to the bipedal King Ghidorah. Second, it is not gold. Desghidorah’s menacing black and charcoal gray body is accented with blood-red wings and highlights. Its heads appear more demonic and less serpentine, featuring armored crests and an expression of pure malevolence. This is no space dragon; it is a demon from the depths of hell. Its powers differ drastically as well. Instead of gravity beams, it breathes fire and lava-like energy. However, its most terrifying ability is to drain the very life force from a planet, transforming vibrant green landscapes into barren deserts. It literally siphons the life out of everything around it, absorbing energy to grow stronger. This makes Desghidorah feel less like a monster that simply destroys cities and more like a true apocalyptic threat—a cosmic plague that travels from world to world, leaving nothing but dust behind.

A Fairy Tale Battle

Like its sequel, Rebirth of Mothra is a children’s film steeped in high fantasy and environmental themes. The story begins with a logging company uncovering an ancient tomb, unleashing the long-imprisoned Desghidorah. The monster immediately begins to prey on the forests of Hokkaido, Japan’s vast northernmost island. It falls to the aging Mothra to halt the destruction. Their battle is both epic and tragic. Mothra, old and weakened, cannot match the demonic behemoth. In a heartbreaking moment, she expends her final strength to save her infant larva, Mothra Leo, before succumbing. The young, inexperienced larva then must confront the planet-destroying demon. The film becomes a coming-of-age tale for a giant insect, where Mothra Leo must grow, transform, and unlock his full power to avenge his mother and save the world. The climax features Mothra Leo undergoing a time-warping metamorphosis by cocooning himself around a thousand-year-old tree, emerging as the mighty Armor Mothra. The confrontation between the radiant, iridescent hero and the dark, demonic villain has the feel of a classic fairy tale. The surreal quality arises from this contrast: a storybook tale of sacrifice and rebirth set against the backdrop of a genuinely terrifying, world-ending monster whose presence alone kills the planet.

The Wilds of Hokkaido

Choosing Hokkaido as the setting was a masterstroke. Known for its vast, pristine wilderness, ancient forests, national parks, and unique wildlife, this region evokes a sense of timeless power—an ideal battleground for mythic creatures. It also carries deep connections to the indigenous Ainu culture, which holds a profound reverence for nature. By having Desghidorah literally drain life from this treasured landscape, the film crafts a strong visual metaphor for environmental destruction. It taps into a deep cultural respect for nature and the fear of losing it. Desghidorah’s dark, fiery, and unnatural design perfectly contrasts with Hokkaido’s lush greenery. It is a monster that feels fundamentally wrong, an invasive force on a planetary scale. This nightmarish creation demonstrates that even within the established framework of a classic monster like Ghidorah, there is always room for radical, terrifying, and wonderfully bizarre reinvention.

The TV Terrors: When Weekly Deadlines Breed Genius

So far, we’ve been exploring the world of cinema, focusing on the big-budget blockbusters of the kaiju genre. However, to uncover the most obscure and bizarre creations, we need to turn to television. During the 1960s and 70s, Tsuburaya Productions, founded by special effects pioneer Eiji Tsuburaya—the visionary behind the original Godzilla—produced the Ultra Series. Shows such as Ultra Q and Ultraman became cultural phenomena, introducing a new monster each week. This relentless production pace, coupled with limited budgets, forced the creature designers to be highly inventive. Complex, articulated suits were often unaffordable, so they had to embrace the strange. The outcome was some of the most surreal, abstract, and unforgettable monster designs in history—pure manifestations of a child’s fever dream.

A Gallery of the Bizarre

Where to start? Let’s discuss Jamila from Ultraman. Jamila was neither an alien nor a mutant dinosaur. He was a human astronaut whose ship crashed, leaving him stranded on a waterless planet. His body mutated into a grotesque, clay-like form, and he eventually returns to Earth seeking revenge on the space agency that abandoned him. His design is heartbreakingly tragic: he lacks a real head, instead having a screaming, misshapen face on his torso. Jamila is one of the most sympathetic yet nightmarish monsters ever created. Then there’s Bullton from the same series. Bullton isn’t an animal; it’s a living, multi-dimensional object—a strange fusion of blue and red meteorites resembling a sea anemone made of rock and metal. It doesn’t engage in combat conventionally but warps reality around it, creating bizarre gravitational and dimensional anomalies. This monster attacks your very perception of reality. And of course, there’s Gavadon, a creature literally born from a child’s doodle on a piece of clay, brought to life by cosmic rays. Its design is goofy and simplistic, looking exactly like something a kid would draw. The episode centers on children trying to protect their monster from authorities who see it as a threat. It’s a narrative that deeply explores the theme of childhood imagination, with the designers making that concept central to the monster’s visual identity. Lastly, we can’t forget Zetton, Ultraman’s final adversary. Zetton’s design is almost minimalist: a sleek black body with yellow, glowing sections on its chest resembling a face. It has no mouth and two simple, horn-like antennae on its head. It emits a creepy, electronic sound and feels less like a living being and more like an abstract embodiment of unstoppable power. Zetton was so formidable it actually defeated and killed Ultraman in the series finale, a shocking twist that traumatized a generation of Japanese children.

The Freedom of the Small Screen

The weekly format of the Ultra Series fostered this kind of creative madness. The monster of the week didn’t need the same weight as a movie villain. It could be silly, tragic, abstract, or just plain bizarre. Designers took risks that would never have been allowed in a big-budget film. They found inspiration in surrealist art, modern sculpture, and everyday objects. This is why the Ultra Series monsters often feel more personal and imaginative than their cinematic counterparts—they represent pure, unfiltered creativity. For any true fan of Japanese monster culture, a visit to Ultraman Shopping Street in Tokyo’s Soshigaya-Okura neighborhood is a must. This is where Tsuburaya Productions was once headquartered, and the entire street honors the franchise with statues of heroes and monsters lining the sidewalks. It’s a celebration of an incredible creative legacy, a place where you can feel the vibrant energy that brought these fantastical fever-dream creatures to life.

The Dream Never Ends

From the psychedelic sludge of Hedorah to the abstract terror of Zetton, the realm of Japanese kaiju extends far beyond a single famous lizard. It is a universe brimming with creations that defy logic, challenge design conventions, and tap into something primal within our imagination. These strange monsters are not errors or accidents; they embody the very essence of the genre. They stand as a tribute to a creative culture unafraid to be bizarre, to embrace the nonsensical, and to discover art in absurdity. They mirror the anxieties of their era, from pollution to cosmic destruction, yet also reflect our dreams, creativity, and capacity to envision the impossible. Delving into these films is like a journey through the subconscious of modern Japan, revealing its fears and fantasies boldly displayed across the skyline. So next time you encounter a monster resembling a cyborg chicken with a buzzsaw for a stomach, don’t dismiss it as silly. Instead, lean in. Value the boldness, the artistry, and the pure, unfiltered joy of creation. Because in the wild world of kaiju, the stranger it becomes, the better it is. The fever dream is the very essence.