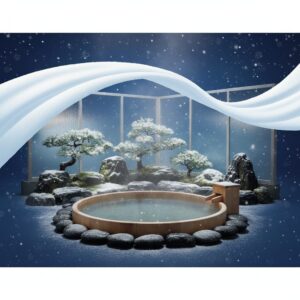

Yo, let’s talk about that picture. You’ve seen it. It’s a core memory for anyone who’s ever doom-scrolled through Japan travel inspo. Steam rising from a stone bath, fat snowflakes drifting down, and some impossibly chill person soaking in the middle of it all, looking like the main character in a Studio Ghibli movie. It’s the peak aesthetic, the ultimate vibe. The setting is usually a ski resort, which adds another layer of cool—literally. Shredding gnarly powder all day, then blissing out in volcanic water while the world freezes around you. It’s a powerful image. But if you’re looking at it from the outside, a few questions probably pop into your head. Like, for real? Is it actually enjoyable, or is it just a flex for the ‘gram? Isn’t it, you know, crazy uncomfortable to be naked outside in a blizzard? And why is this specific, slightly insane-sounding activity such a huge deal in Japan? It feels like more than just a hot tub. You get the sense that there’s a whole cultural iceberg under the surface of that steaming water. And you’re right. This isn’t just Japan’s version of a post-ski beer. It’s a deep dive into the Japanese psyche, a physical manifestation of its philosophies on nature, community, and the art of feeling truly alive. So, let’s get into it. Let’s unpack the lore behind the snowy rotenburo and figure out why the Japanese are so committed to this beautiful, contradictory, and totally extra ritual. It’s a whole mood, and it’s about time we decoded it.

If you’re captivated by the retro ski resort aesthetic in that viral photo, you might also appreciate the timeless appeal of Shōwa-era ski fashion.

The Aesthetics of Contrast: More Than Just a Pretty Picture

First, you need to realize that the visual charm of the snowy rotenburo is no happy accident; it’s the whole point. In the West, comfort often means crafting a uniform, controlled environment—think plush carpets, central heating, perfectly scented candles—eliminating all harshness. Japanese aesthetics, however, tend to go in the opposite direction. They find beauty not in avoiding harshness, but in its sharp contrast with tranquility. The experience is a living, breathing work of art, with your body right at its center.

‘Wabi-Sabi’ Reimagined as Extreme Sports

This scene is essentially a high-energy take on traditional Japanese aesthetic principles. You’ve probably heard the term wabi-sabi, often defined as appreciating beauty in imperfection, impermanence, and incompletion. A snowy onsen embodies wabi-sabi in its rawest form. Snowflakes are the ultimate symbol of fleeting beauty—each unique, perfect for a brief moment, then gone forever, melting on your skin or into the hot water. The steam rising and swirling into the cold air adds another ephemeral layer. Nothing in this moment is fixed or permanent. You can’t capture it; you can only live it as it passes. This forces an intense mindfulness—you’re not thinking about emails or tasks. Instead, you’re fully immersed in the sensory present: the heat, the cold, the sound of falling snow, the smell of sulfur permeating the air. This is the aim. A meditative state reached not through silent contemplation in a sterile space, but through immersive sensory overload in a wild setting.

Then there’s mono no aware, a gentle, melancholic awareness of life’s transience. It’s the bittersweet feeling watching cherry blossoms fall. The snowy onsen taps into this same emotional thread. There’s profound beauty in knowing this perfect moment—the snow falling just so, the water at just the right temperature—is fleeting. It makes the experience more precious, more poignant. This isn’t about crafting a lasting photo for Instagram; it’s about surrendering to a moment you know will vanish. The contrast is what creates the beauty. The raw, untamed force of the winter landscape is held at bay by the circle of volcanic warmth you sit in. It’s a pocket of life and heat within a world that seems dormant or dead. This duality is central to much Japanese art and philosophy—the idea of finding a small, curated space of order and peace amid vast, chaotic nature.

The Body as Nature’s Canvas

This experience aims to dissolve the boundary between you and the natural world. It’s a full-body sensory encounter, in the best sense. In a typical spa, you’re shielded from the elements; here, the elements take center stage. The sensation of snowflakes, once just cold and wet, transforms completely when they land on your hot skin. They don’t chill you; they sizzle and vanish—brief, intimate moments of contact. It’s a deeply personal interaction with the weather. Your shoulders and head, exposed to the frigid air, serve as grounding points, keeping you alert and aware, while your body is wrapped in a primal, womb-like warmth. This sharp division between the part of you submerged and the part exposed heightens your awareness of your body and its physical presence.

Sound is just as crucial. In many rotenburo, especially those nestled in rural ski resorts, profound silence is broken only by the gentle hiss of falling snow and soft water lapping. This isn’t the artificial hush of a soundproofed room but the weighty, textured silence of a snow-blanketed world. Heightened senses, sharpened by extreme temperatures, catch everything. You’re not merely observing nature; you’re letting it wash over you. The goal is to lose the sense of yourself as an outsider and instead feel like part of the landscape. It rejects the idea that humans should be protected from nature. Instead, it suggests that the deepest experiences come from engaging nature on its own terms, feeling its full power, and finding harmony within it.

Beyond the ‘Gram: The Social and Physical Logic of the Snow Onsen

The aesthetics are undeniably impressive—it’s a mood. However, the cultural importance of the snowy onsen runs much deeper than just looking stylish. There’s a practical, social, and even therapeutic rationale behind why it became Japan’s quintessential après-ski activity. It isn’t merely a luxury; for many, it’s an essential part of the entire skiing and snowboarding experience, intricately embedded in the culture of winter leisure.

The Ultimate ‘Après-Ski’: A Cultural Exploration

When people outside Japan think of ‘après-ski’, they often imagine crowded slope-side bars, booming music, dancing in ski boots, and plenty of alcohol. While that scene exists in some of Japan’s more international resorts, the heart of Japanese après-ski is quieter, more restorative, and takes place in the onsen. Consider the physical toll of a day spent skiing or snowboarding: aching muscles, sore joints, and chill running through your body. From a practical perspective, immersing your weary body in mineral-rich, naturally heated volcanic water is among the most effective ways to recover. The heat relieves muscle soreness, boosts circulation, and helps avoid the dreaded stiffness the next day.

This isn’t just a superstition; it’s rooted in the ancient practice of toji, or therapeutic hot spring bathing. For centuries, people in Japan have visited onsen towns not only for leisure but for genuine health benefits, often staying for weeks to treat conditions from rheumatism to skin ailments. Each onsen offers a unique mineral composition—some high in sulfur, others in iron or magnesium—that is believed to provide specific healing effects. So, when a skier immerses themselves in an onsen after a long day, they are not merely warming up; they are engaging in a time-honored tradition of using nature as medicine. It’s a deeply embedded cultural habit: physical exertion is followed by natural recuperation. The bars and parties can wait. The priority is to reset and heal the body. This approach transforms the onsen from a simple pleasure to a crucial ritual.

‘Hadaka no Tsukiai’ (Naked Communion) in the Snow

Now, let’s address the obvious: everyone is naked. For many visitors, this is the biggest psychological hurdle. In many Western cultures, public nudity is sexualized or considered embarrassing. In Japan, the context is entirely different. The onsen is a non-sexual, communal space where nudity plays a key social role. This is the essence of hadaka no tsukiai, which literally means “naked relationship” or “naked communion,” but arguably better translated as “leveling the playing field.”

Japanese society can be very hierarchical and formal. Your status, job title, company, and age all shape how you interact with others. Clothing is part of this social uniform, signifying your position. When you remove your clothes, all of that social armor vanishes. The CEO and the intern, the professor and the student, become simply two people sharing hot water. This creates a distinctive social atmosphere where communication can be more direct, honest, and relaxed. Barriers come down. It’s common for important business relationships to be strengthened or friendships deepened in the onsen. Sharing the vulnerability of nakedness, combined with the intense physical contrast of hot water and cold air, builds a powerful sense of camaraderie and shared experience. On a ski trip with friends or coworkers, the onsen is the ultimate bonding ritual. You’re not just recounting the day’s runs; you’re sharing a moment of collective surrender and contentment, forging connections beyond words.

Is it Awkward? Understanding the Unspoken Rules

Is it strange for a first-timer? Let’s be honest: it definitely can be. The first time you enter the changing room, it may feel daunting. But the key to appreciating the onsen lies in understanding the strict unspoken rules that maintain a respectful and comfortable environment for all. These guidelines facilitate the entire hadaka no tsukiai experience. First and foremost is the rule of washing. Before entering the onsen water, you must thoroughly wash your entire body at the provided shower stations. This hygiene rule is non-negotiable—you enter the bath clean. Second, the large towel you use for drying stays in the changing room. The only item allowed in the bathing area is a small washcloth, often called a “modesty towel.” You can use it for modesty while walking to the bath but it must never enter the water. Most people fold it and rest it on their head while soaking. Third, the onsen is not a swimming pool—there’s no splashing, loud talking, or swimming. It’s a place for quiet reflection and relaxation, with a serene and almost reverent atmosphere. Finally, you don’t stare. Everyone minds their own business—people are there to relax, not judge or be judged. Once you grasp these rules, you see they form a social contract allowing everyone to feel safe. The initial awkwardness quickly fades, replaced by an appreciation for this unique form of shared, peaceful vulnerability.

The Reality Check: What the Photos Don’t Show You

We’ve praised the magic and allure, but now it’s time for some honest talk. The perfectly styled Instagram photo of a calm snow monkey meditating in a steaming bath is exactly that—a carefully composed image. The reality of the human experience in a snowy rotenburo includes moments of discomfort, indignity, and surprising sensations that are conveniently left out of the picture. To get the full experience, you have to accept the less glamorous aspects, because, frankly, they are an essential part of the story.

The Mad Dash of Desperation

Let’s begin with the trek from Point A (the warm, cozy changing room) to Point B (the wonderfully hot onsen). Though it’s only about ten to twenty feet, it feels like an arctic expedition. The photos never show this stage. They don’t capture the moment you open the door and are hit by a blast of sub-zero air on your completely naked, wet body like a slap. The floor is often covered in ice or snow, triggering an immediate, primal panic. There is no slow, graceful walk to the bath—only a frantic, arms-flailing, high-stepping scramble over slippery ground, driven by the desperate need to plunge into hot water before you turn into a human popsicle. It’s pure chaos. Your teeth chatter, you try not to slip and hurt yourself, and any trace of zen-like calm is gone. This comical, awkward sprint is the price of entry. It’s a rite of passage—you must endure the extreme cold to truly appreciate the searing heat. The relief when you finally settle into the water is so intense precisely because the journey there was so harsh.

Not All Snowy Onsen Are Created Equal

The ideal image is a secluded, natural rock pool with sweeping views of a pristine, snowy valley. The reality, however, can vary widely. It’s important to note that ‘rotenburo’ simply means ‘outdoor bath.’ It doesn’t promise breathtaking scenery or a rustic vibe. Some rotenburo at ski resorts are, frankly, concrete or tiled tubs enclosed by wooden fences, overlooking a hotel parking lot. They often get crowded, especially during peak times, turning your dream of a tranquil nature soak into a crowded affair where you try to avoid awkward elbow bumps with strangers. The water temperature can also fluctuate. While many onsen draw from natural volcanic springs, the heat isn’t always perfectly controlled. You might find yourself in scalding hot water, forcing you to sit on the edge, or, nearly as bad, in lukewarm water that doesn’t provide enough warmth against the freezing air. And there’s the smell—many volcanic springs are high in sulfur, giving the water a strong rotten egg odor. For some, this is an authentic, earthy scent; for others, it’s a shocking surprise. Picture-perfect onsen do exist, but finding one often requires research, luck, or a trip to more remote, traditional inns (ryokan).

The ‘Nobose’ Phenomenon

There’s a physical effect few glossy travel blogs mention: the head rush. Soaking in very hot water (often 40-42°C / 104-108°F) with your head exposed to cold air causes unusual changes in circulation. It can make you feel dizzy, lightheaded, or even nauseous. This sensation is called nobose in Japanese and signals that you’re overheating. This is why people place a small, cold, wet towel on their heads—not just a charming tradition, but a simple cooling device to regulate body temperature and keep your brain from overheating. It’s also why you shouldn’t stay in the bath too long at once. The proper way to enjoy an onsen is to soak for 5-10 minutes, then get out to cool down for a few before going back in. It’s a marathon, not a sprint. Trying to see how long you can last is a rookie mistake that can lead to fainting. The goal is relaxation, not endurance. True onsen aficionados master the art of moderation.

So, Why Bother? Connecting the Dots

After hearing about the awkward nudity, the mad dash through the snow, and the potential for a dizzying head rush, you might be wondering, ‘This sounds like a lot of effort. Is it truly worth it?’ From a cultural standpoint, the answer is a definite yes. The challenges, discomforts, and strict rules aren’t flaws in the system; they are integral features. The entire experience encapsulates a broader Japanese philosophical view: true satisfaction and happiness are not handed to you freely. They must be earned through ritual, endurance, and a profound appreciation of the moment.

The Pursuit of ‘Gokuraku’ (Paradise) on Earth

In Japanese Buddhism, Gokuraku refers to the Pure Land, or paradise. In a more secular, everyday sense, it describes a state of supreme bliss or heaven on earth. The sigh of contentment from an elderly man sinking into onsen water is often accompanied by the word ‘gokuraku, gokuraku.’ This is more than a casual expression of pleasure. It embodies the idea that this experience—the relief from cold, the soothing of tired muscles, the quiet reflection in a beautiful setting—is a small taste of paradise. However, this paradise is only attainable after a trial. You must follow the rules for washing. You must endure the physical shock of the cold. You must respect the communal space. In essence, you have to practice a form of discipline. The enjoyment is deepened by the hardship that precedes it. This pattern of ‘endurance followed by reward’ is a recurring theme in Japanese culture, from the demanding training of martial artists to the meticulous process of traditional crafts. The snowy rotenburo is the leisure-time counterpart. It teaches, on a physical level, that the greatest pleasures in life come not from passive consumption but from active participation and surmounting a challenge, no matter how small.

A Rejection of the Sanitized Experience

In an increasingly digital, sanitized, and physically disconnected world, the onsen—especially a wild, snowy rotenburo—serves as a powerful counterbalance. It is boldly, unapologetically analog. It compels you to be fully present in your body and in the raw, unfiltered environment. You can’t bring your phone into the bath. You can’t tailor the experience beyond choosing which onsen to visit. You are subject to the unpredictable weather, the water temperature, and the quiet presence of strangers. In a society like Japan’s, known for its high-tech efficiency, social order, and often overwhelming urban density, the onsen functions as an essential outlet. It provides a space to reconnect with something more primal and elemental. It’s a moment to shed not only your clothes but also your social identity—your job title, responsibilities, and digital persona—and simply exist as a human being in nature. This act of shedding is a profound release. It offers temporary liberation from the pressures of a highly structured society. The untamed, snowy mountain setting provides the perfect backdrop for this internal reset. It serves as a reminder that beneath the layers of civilization, we are all creatures seeking warmth and comfort in a vast, sometimes cold world.

The Final Takeaway: It’s Not Just a Hot Tub

By now, it should be evident that when you see that picture of a snowy rotenburo, you’re not merely looking at an elegant outdoor hot tub. You’re witnessing the culmination of centuries of Japanese culture, aesthetics, and social dynamics, all converging in one steamy, sublime instant. It’s as much a cultural artifact as it is a leisure activity. The confusion it might cause for an outsider is entirely understandable, as it blends together a variety of concepts often kept separate in other cultures: intense physical hardship and deep relaxation; public, communal space and private, introspective meditation; ancient tradition and modern recreation; complete vulnerability and strict social rules.

The true magic of the snowy rotenburo, and the explanation for “why Japan is like this,” lies precisely in its capacity to hold all these contradictions in perfect, harmonious balance. It’s an experience that demands your full attention and rewards you with a peace that is profound and resonant. It’s not about achieving a state of constant, effortless comfort. It’s about finding a moment of perfect, well-earned bliss at the extreme intersection of heat and cold, body and nature, self and community. So, is it worth the awkwardness and the freezing dash? Absolutely. Because in that moment, when the snowflakes melt on your face and the volcanic water embraces you, you don’t just get a striking photo—you get a glimpse into the heart of a culture that has mastered the art of discovering paradise in the most unexpected places.