Yo, let’s take a trip. Not just to Japan, but to a different time in Japan. We’re dialing it back to the 90s, a legit analog era before the internet was in everyone’s pocket, before social media defined communities, and before creating art was just a click away. We’re diving headfirst into the world of Dojinshi—specifically, the raw, unfiltered, maker-vibe of the Dojinshi fairs that pulsed with a creative energy that was, no cap, legendary. Forget your sleek digital tablets and cloud-based portfolios for a sec. We’re talking about a time of paper cuts, the smell of fresh ink, the crinkle of photocopied pages, and the sheer hustle of creators who were artists, writers, publishers, and marketers all rolled into one. This was the underground scene where fandom wasn’t just about consuming content; it was about creating it, physically, with your own two hands. It was a community built on passion, mailing lists, and standing in line for hours just to get your hands on a stapled, black-and-white zine made by your favorite circle. This is the story of that vibe, a vibe so powerful its ghost still haunts the massive halls of modern conventions. To understand where this culture lives now, you gotta know its heart, and for many, that heart beats at Tokyo Big Sight, the iconic modern home of the biggest Dojinshi event, Comiket. So let’s set our map there, but keep our minds in the past.

This raw, analog energy is reminiscent of the nostalgic, community-driven atmosphere you can still find today in Japan’s historic yokocho alleys.

So, What’s the Tea on Dojinshi?

Before we can properly understand time-travel, we need to grasp the basics first. So, what exactly is Dojinshi? If you’ve spent any time in anime or manga fandom communities online, you’ve likely come across the term, though it’s often misunderstood. Simply put, Dojinshi (同人誌) refers to self-published works. The term breaks down to ‘dōjin’ (同人), meaning ‘same person’ or a group of people sharing the same interests, and ‘shi’ (誌), which means magazine or publication. In essence, it’s a ‘publication for people with shared interests.’ It represents the purest form of ‘for the fans, by the fans.’

This isn’t limited to just fanfiction or fan art, even though those are significant and vibrant parts of it. Dojinshi can encompass anything and everything—manga, novels, art books, essays, photo collections, and even music or games. The crucial factor is that it’s independently created and distributed, existing entirely outside the mainstream corporate publishing world. It’s a space for complete creative freedom. Want to write a story centered on a minor character from your favorite 90s mecha anime embarking on their own epic adventure? Go ahead. Want to draw a gag manga parodying a serious fantasy series? The stage is yours. Want to invent an entirely original story with your own characters and world? That’s Dojinshi too, known as an ‘original work’ or sousaku (創作).

The most common type you’ll encounter, especially at massive events like Comic Market (or Comiket, as it’s widely called), is based on existing media—anime, manga, video games, and so forth. This is known as niji sousaku (二次創作), or ‘secondary creation.’ This is where the true fandom spirit of Dojinshi shines brightest. It’s a medium where creators can explore ‘what if’ scenarios, ship their favorite characters, or simply linger longer in a world they adore. It serves as a conversation between fans and the source material, allowing for a deeply personal and creative connection to the story. But it’s important to note that it’s not all parody or romance. There are profoundly serious works, intricate alternate universe plots, and breathtakingly beautiful art books that can rival professional publications. The quality and diversity are truly astonishing, and have been for decades.

The 90s Vibe Check: An Analog Fever Dream

Now, let’s dive into the heart of it all: the 90s. This decade marked a crucial turning point for Dojinshi culture. The otaku identity was taking shape, heavily influenced by groundbreaking anime like Neon Genesis Evangelion and Sailor Moon, which offered incredibly fertile ground for fan creators. Yet, technology was still predominantly analog for most people. There was no Pixiv, no Twitter for instant art sharing, no Procreate on iPads. The effort was real—and hands-on. This limitation wasn’t a flaw; it was a defining feature. It fostered a culture of dedication, craftsmanship, and a distinctive community that’s truly fascinating to reflect on.

The Art of the Analog Grind

Picture the scene: a small Tokyo apartment late at night, lit only by a desk lamp shining on a drawing board. This was the creator’s sanctuary. The tools weren’t digital brushes or layers but G-pens, maru-pens, and kabura-pens, each with a unique nib producing distinct line weights. Artists had to dip these pens in bottles of black ink—Pilot ink being a classic favorite. The muscle memory required to create a clean, expressive line with a G-pen could only be built through thousands of hours of practice. One shaky hand or a single misplaced drop of ink might mean starting the whole page over. There was no Command+Z.

After completing the line art on specialized manga paper from brands like Deleter or IC, shading and texture followed. This wasn’t the era of digital gradients but the reign of screentones. For the uninitiated, screentones are transparent adhesive sheets printed with patterns—dots, lines, gradients, sparkles, and more. Applying them was an art in itself. The creator would carefully place the tone over the inked drawing, gently rub it to adhere, and then, with an extremely sharp craft knife, painstakingly trim the excess away. They’d carve around characters, cut out highlights, and layer various tones to build depth. It was meticulous, precise work—you could hear the subtle scrape-scrape of the knife on plastic, the true soundtrack of 90s manga creation. The wide variety of tones available was astounding, and a creator’s skill was often judged by how innovatively and cleanly they applied them.

Then came the lettering. No font libraries were at hand. Dialogue, sound effects, and narration were usually handwritten. To achieve a more professional look, creators sometimes used rub-on transfer letters, a process just as delicate as applying screentone. Every element on the page was crafted by hand. It was genuine craftsmanship. The finished pages had a tactile quality—you could sometimes feel the raised edges of dried ink or the subtle texture of applied tones. It was an object, not just an image.

Printing, Binding, and the Hustle

Once the manuscript was finished, the journey was far from done. Now the creator had to step into the role of publisher. For many, this meant a trip to the local copy shop, where they’d run off dozens or even hundreds of copies of their precious work. The quality varied greatly depending on the machine and budget—some copies were sharp and clean; others faded, lending a classic zine charm. It was all part of the experience.

The final step was binding, typically done through saddle-stitching—a simple yet effective method of folding pages in half and stapling the spine with two or three staples. This was a DIY process, often completed by the creator and friends in a frantic, last-minute assembly line the night before a major fair. Stacks of collated pages filled the floor, a long-arm stapler operated nonstop, and there was a shared feeling of exhausted, exhilarating accomplishment. Holding that finished Dojinshi—a physical book brought to life through ink, paper, and staples—was a sensation a digital file could never replicate. It was your book. You made it.

The Fairground: A Pre-Internet Social Hub

The Dojinshi fair itself marked the pinnacle of this entire process. Before the internet linked everyone together, these events were the main way for creators and fans to interact. They were the tangible embodiment of the community. In the 90s, before Comiket permanently relocated to the futuristic, vast Tokyo Big Sight in 1996, it and other events took place in various venues, such as the Tokyo International Trade Center in Harumi or smaller halls dotted around the city. The atmosphere was electric, yet also intensely dense and humid, filled with the body heat of thousands of passionate fans and the unmistakable scent of paper and ink.

Navigating the Sea of Creativity

You’d arrive early, clutching a hand-drawn map or a printed catalog you had purchased ahead of time. These catalogs served as a bible, specifying which ‘circles’ (the term for a creator or group of creators) would be at each table. You’d have your must-visit spots circled, your route mapped out, and a cash budget in your wallet. When the doors opened, it was a flood—a polite, orderly flood, but a flood nonetheless.

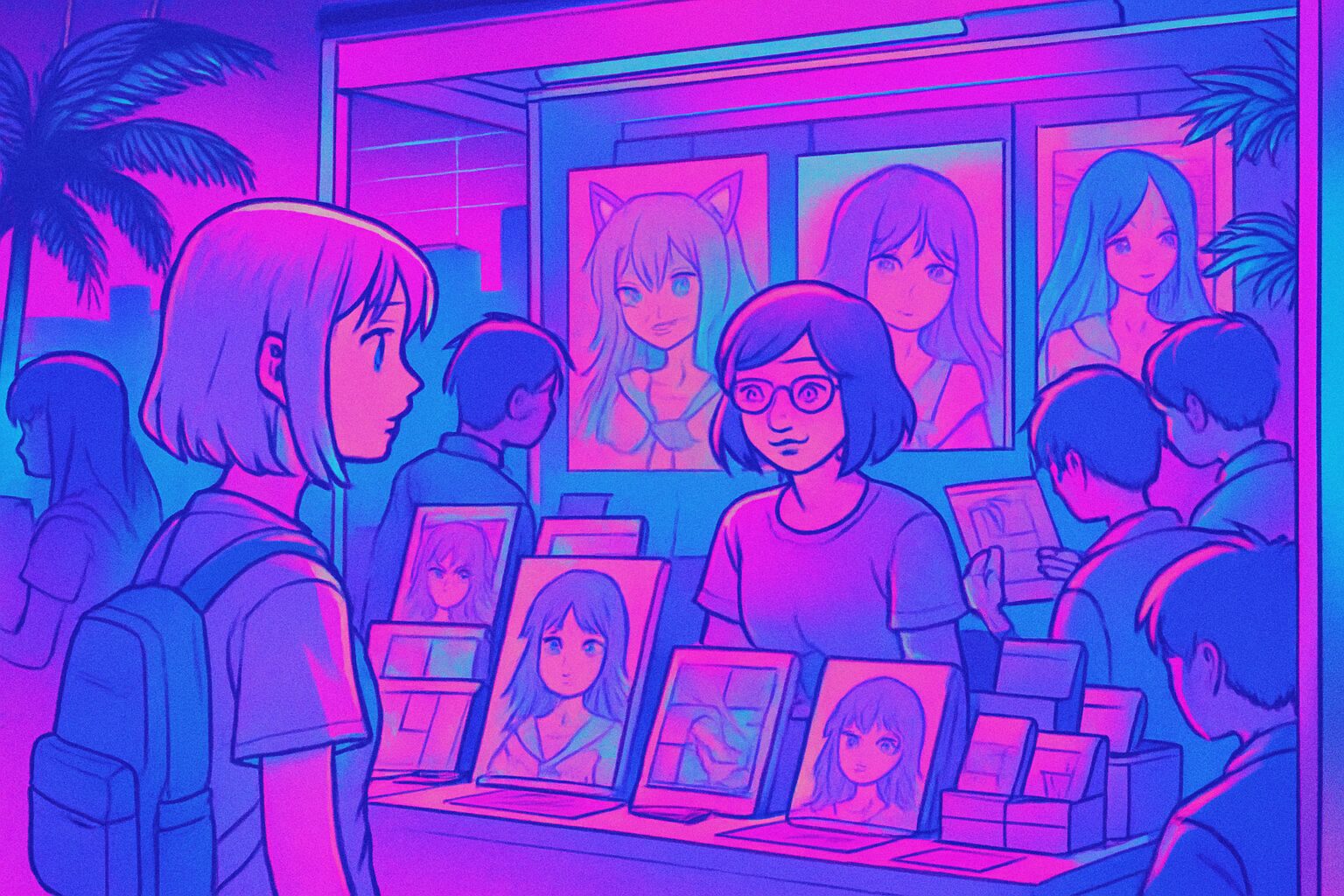

The sound was a low roar of chatter, the constant rustle of thousands flipping through paper pages, the crinkle of plastic bags as people stored their treasures. Unlike the often silent, focused convention floors of today, there was a vivid buzz of conversation. Fans eagerly engaged with creators, raving about their previous work and asking questions about the story. There was a direct, face-to-face connection that social media comment sections can only dream of reproducing.

You’d move from table to table, each one a small, personalized storefront. Circles decorated their spaces with hand-drawn signs, maybe a small display stand, and neat stacks of their latest Dojinshi. The creators themselves sat right there—often a bit nervous, a bit excited. The transaction was intimate. You handed over your money, they handed you their book, and a moment of shared understanding passed between you. You both loved this thing. You belonged to the same tribe. It was an IYKYK moment happening a thousand times a minute.

Communication in the Analog Age

How did people even learn about these circles before Twitter? It was an entirely different ecosystem. Communication was a deliberate act. Creators included a final page in their Dojinshi called the atogaki, or afterword. This was their blog, social media feed, direct line to the reader. They’d discuss the challenges of drawing the book, hint at upcoming projects, and, most importantly, provide contact information. This was often a P.O. box address. Fans wrote actual, physical fan mail—letters filled with praise and thoughtful feedback—and sent them off, hoping for a reply. It was slow, deliberate, and deeply meaningful.

Circles also built mailing lists. You could sign up at their table, and they would periodically send newsletters or flyers, often beautifully designed and photocopied, announcing their next book or event appearance. It was a tangible connection. Receiving a flyer in the mail from your favorite circle was a special event. Some circles even created their own ‘paper,’ a sort of mini-fanzine handed out for free, containing small comics, essays, and updates. This entire network—built on paper and postal services—fostered a sense of discovery and dedication. You had to put effort into being a fan, which made the bond with the creators and community all the stronger.

The Cultural Shift: Otaku in the Spotlight

The 90s were not solely defined by the tools and processes; they also marked a period of significant cultural transformation. The image of the ‘otaku’ began to shift. Though previously associated with negative stereotypes, the mainstream success of certain anime started to alter the narrative. Neon Genesis Evangelion, which premiered in 1995, was a pivotal moment. It was a complex, psychoanalytic, and visually striking work that invited analysis and interpretation. It seemed almost designed to inspire Dojinshi. Its mysterious characters and ambiguous storylines provided a blank canvas for fan creators to explore, debate, and expand upon. Visiting a Dojinshi fair in the late 90s, you would have found yourself immersed in countless works centered around Shinji, Asuka, Rei, and Kaworu.

Likewise, shows like Sailor Moon cultivated a vast and devoted female fanbase that found a powerful creative outlet in Dojinshi. Fans explored relationships between the Sailor Guardians, crafted new adventures, and built a universe of content celebrating female friendship and empowerment. The 90s offered abundant source material, from epic RPGs like Final Fantasy VII to cherished manga like Slam Dunk. Each inspired its own thriving Dojinshi community—a collective of creators who kept these worlds vibrant long after the final episode aired or the game was completed.

All of this unfolded amid Japan’s ‘Lost Decade,’ a period of economic stagnation following the collapse of the bubble economy in the early 90s. During this era of social and economic uncertainty, these hobbies and communities gave many young people a vital sense of identity and purpose. The Dojinshi world was a space they could control, where passion and dedication could produce tangible works and foster genuine connections. It was a low-cost, high-reward form of entrepreneurship driven purely by love for the craft.

Chasing the Ghost: Finding the 90s Vibe Today

Okay, so we can’t literally travel back in time to the 1997 Comiket. Bummer, I know. But the essence of that era isn’t completely gone. Its whispers remain if you know where to look and listen carefully. Dojinshi culture has grown tremendously, yet its core spirit endures. Experiencing the legacy of this analog golden age is a pilgrimage every pop culture enthusiast visiting Japan should consider.

The Treasure Troves: Mandarake and K-Books

Your first stop on this quest should be the revered stores like Mandarake or K-Books. These are meccas for second-hand otaku merchandise, featuring extensive sections devoted to Dojinshi, both vintage and new. The Nakano Broadway branch of Mandarake is the GOAT—a vast complex that feels like a museum curated by fandom’s collective memory. Entire walls are lined with Dojinshi, sorted by series and occasionally by circle.

Here, you can physically hold the history we’re talking about. Hunt for the Dojinshi from the 90s. You’ll recognize them by their style. The covers may be slightly faded, and the paper inside has that soft, aged texture. Printing may be imperfect, with blacks less deep than modern digital prints. You’ll spot the hallmarks of analog craftsmanship: clean, fluid G-pen lines and the unique dot patterns of screentone. You can literally see the artistry on the page. It offers a tactile experience unlike holding a glossy, digitally printed book. Flipping through one feels like discovering a secret message from a creator two decades ago. It’s an archaeological dive into fandom’s heart—truly a vibe.

Experiencing Modern Comiket

Then there’s the main attraction: Comiket itself. Held twice yearly—summer and winter—at the massive Tokyo Big Sight, it’s an experience like no other. It’s a direct descendant of the 90s fairs but scaled to an almost unimaginable magnitude. Hundreds of thousands attend over several days. The DIY spirit thrives, now alongside circles that are practically professional indie publishers, employing digital tools to produce stunning work.

To make the most of modern Comiket, you need a strategy. It’s all about main character energy, but preparation is key. First, purchase the catalog in advance (available in print and digital) and plan which circles to visit. The venue is divided into enormous halls by genre, so knowing your route is essential. Second, bring cash—lots of it, in small bills. Most circles don’t accept cards. A 1000 yen note is your best friend. Third, comfort matters. You’ll be on your feet for hours. Wear your comfiest shoes. Summer Comiket is famously hot and humid—pack water, a small towel, and maybe a personal fan. Winter Comiket can be cold outside but stifling inside, so dress in layers.

The atmosphere remains electric. The sound still hums with the noise of people and paper. And the core interaction is unchanged. You approach a table, point to the book you want, hand over the money with a quiet “arigatou gozaimasu,” and share a fleeting moment of connection. Although many creators now use Twitter and Pixiv to engage fans year-round, the face-to-face appreciation at Comiket is still the real MVP. It’s the highlight of their hard work, and you can see their joy when someone loves their creation. The analog ghost lives on in that simple, human exchange.

A Final Word: The Enduring Maker Spirit

Dojinshi culture, particularly the analog feel of the 90s, powerfully reminds us that fandom is not passive. It’s a driving force for creation. It’s about loving something so deeply that you’re compelled to add your own voice, your own story, to its universe. The creators of the 90s, equipped with pens, paper, and a stapler, embodied a pure maker spirit. They were pioneers of a grassroots creative economy, carving out a world beyond the mainstream.

Today, the tools have evolved. The community is global and instantaneous. Yet the core impulse remains unchanged. Whether it’s a hand-drawn zine from 1995 or a digital art book launched on a whim, the heart of Dojinshi is the urge to create and share. It’s a culture of passion, dedication, and immense hard work. So next time you’re in Japan, wander into a Mandarake. Brave the crowds at Comiket. Look beyond the glossy covers and discover the history beneath. You’ll sense the ghosts of a thousand creators hunched over their desks, the scent of ink and paper, and the unbeatable, enduring thrill of making something, anything, purely for the love of it. Bet.