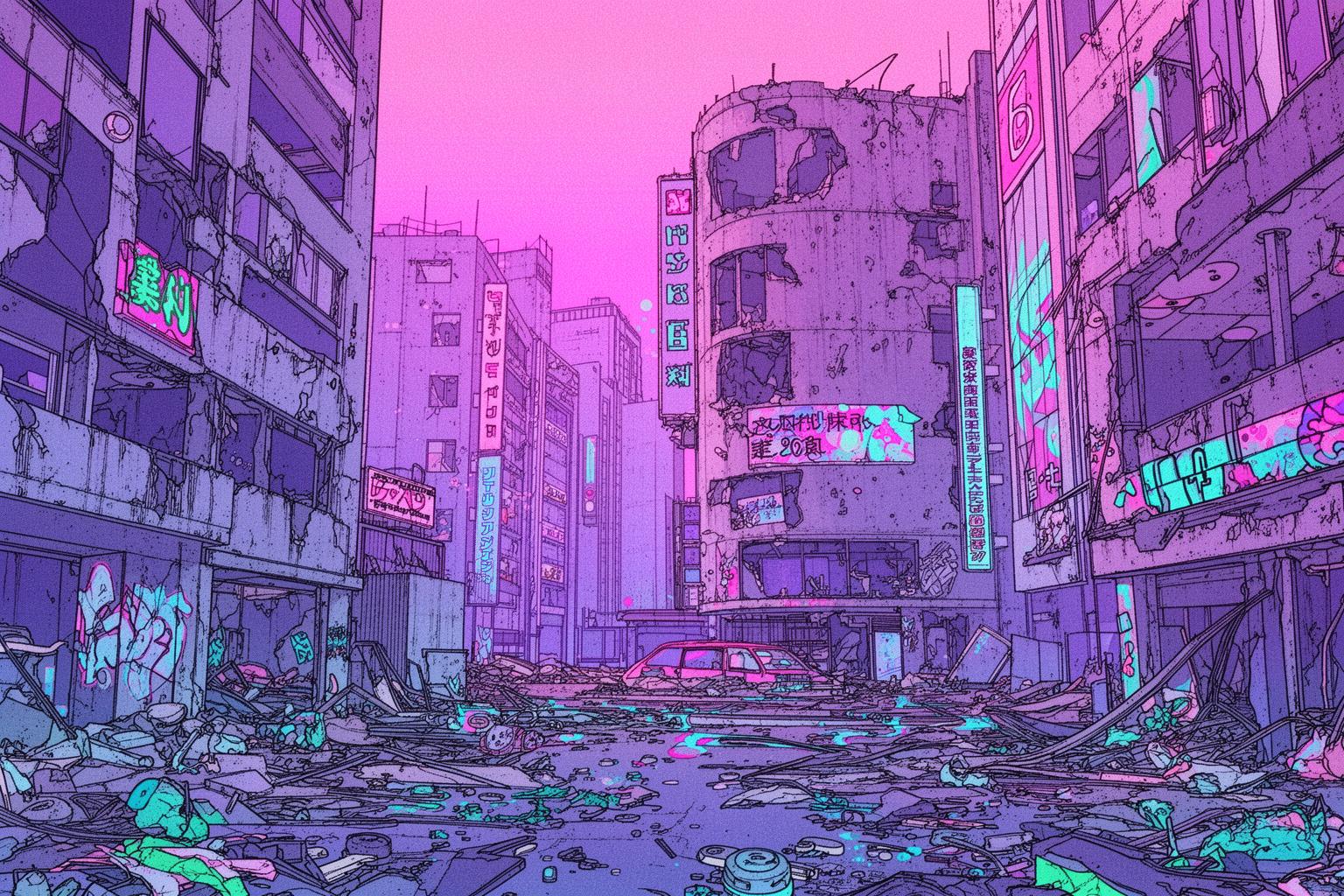

Yo, what’s poppin’, world travelers and culture vultures? Hiroshi Tanaka on the mic, coming at you straight from the heart of Japan. Today, we ain’t talking about serene temples or the neon chaos of Shibuya, nah. We’re going deeper. We’re talking about ghosts. Not the spooky kind, but the ghosts of a wild, high-flying era—the Japanese Bubble Economy. See, back in the late ’80s and early ’90s, Japan was basically living in a music video. The economy was on fire, cash was flowing like a waterfall, and everyone thought the party would never stop. The motto was literally ‘go bigger, go flashier, go crazier.’ And out of this epic, champagne-fueled dream, mega-resorts were born. We’re talking sprawling French palaces on volcanic islands, massive American cowboy towns in the mountains, and futuristic water parks that looked like they were ripped from a sci-fi flick. They were monuments to a future that seemed guaranteed. But then, the beat stopped. The bubble burst, the economy crashed, and the party was over. These pleasure domes, once brimming with life, emptied out almost overnight. They were left behind, locked up, and handed over to the slow, silent forces of time and nature. This is where our story begins. We’re diving into the world of ‘Haikyo’—the Japanese word for ruins, but it’s more than that. It’s a vibe. It’s the art of exploring these forgotten places, feeling the echoes of the past, and finding a strange, haunting beauty in the decay. It’s about understanding a whole chapter of Japan’s history not through a textbook, but through peeling wallpaper and silent, empty swimming pools. These aren’t just rotting buildings; they’re time capsules of a dream, and exploring their stories is a whole different kind of Japanese adventure. It’s a low-key pilgrimage to the altars of ambition. So buckle up, ’cause we’re about to take a tour of the most legendary Bubble-Era resorts that are now giving us major haikyo energy. It’s a trip, for real.

If you’re fascinated by the eerie beauty of these abandoned resorts, you might also be drawn to the post-apocalyptic atmosphere of Japan’s abandoned amusement parks.

The Concrete Kings: When Japan Dreamed Too Big

To truly grasp the situation, you need to understand the mindset of the Bubble Era. It was sheer, unfiltered optimism. The Nikkei stock index was skyrocketing, and real estate prices in Tokyo were so absurd that the land beneath the Imperial Palace was said to be worth more than all of California—no joke. People felt unstoppable, and companies, flush with cash, were eager to spend it. Meanwhile, the government was promoting a massive national initiative. In 1987, they passed the ‘Resort Law,’ which offered huge tax breaks and incentives to firms building large-scale leisure facilities. The goal was to encourage urban residents to spend their time and money vacationing in rural areas, thereby revitalizing those communities. The outcome? A genuine construction boom. It turned into a nationwide competition to create the most extravagant, unique, and unforgettable resort imaginable.

This wasn’t just about building a few upscale hotels. It was about crafting entire worlds. Developers traveled to Europe to study castles, imported marble from Italy, and hired top architects to design gravity-defying structures. The architectural style of the era was unmistakable. It embraced post-modern extravagance, featuring grand sweeping curves, soaring glass atriums, and bold, often gaudy color schemes. Many resorts adopted foreign themes—a German-style village in the mountains, a Spanish coastal resort, a Swiss alpine hotel. It was pure fantasy, allowing Japanese tourists to experience a ‘trip abroad’ without ever needing a passport. These massive resorts were constructed in some of Japan’s most stunning and often remote areas—secluded coastlines, deep snowy mountains, or subtropical islands. They were designed as self-contained worlds of entertainment where visitors could ski, swim, play golf, and dine at five-star restaurants all in one place. The ambition was surreal. They were building not just for the present but for a future where everyone would be wealthier, have more leisure time, and demand ever-greater levels of luxury. It was a beautiful dream—but it was built on a bubble, and everyone knows what eventually happens to bubbles.

Case File 01: The Hachijo Royal Hotel – A French Palace Ghosting on a Volcanic Island

Our first destination is a legend—the undisputed king of haikyo hotels. To reach it, you have to venture out into the Pacific, to a place technically part of Tokyo but feeling like a world apart: Hachijojima island.

The Island Atmosphere: What Hachijojima’s All About

First things first, Hachijojima has a vibe of its own. It’s a subtropical, volcanic island within the Izu archipelago that stretches southward from Tokyo. Imagine lush, green mountains reminiscent of Jurassic Park, striking black-sand beaches, and an easygoing, laid-back mood. Once known as a place of exile, in the 20th century, it transformed into a popular honeymoon destination, earning the moniker ‘the Hawaii of Japan.’ The atmosphere is a blend of rugged natural beauty and classic resort town charm. It was against this wild, stunning backdrop that one of the Bubble Era’s boldest projects arose.

Living Like Royalty: The Bubble Era Dream

The Hachijo Royal Hotel opened its lavish doors in 1991, right at the height of the economic bubble. Its timing was both impeccable and tragic. The concept was pure fantasy: a French Baroque palace on a Japanese volcanic island. Imagine a grand European hotel, a piece of Versailles dropped into the middle of the Pacific. From the moment you stepped inside, you were meant to be transported. There was a colossal central atrium with an enormous, ornate fountain, sprawling marble floors extending in every direction, and twin spiral staircases that could easily rival those in a Disney castle. Sunlight poured through a massive glass ceiling, sparkling off crystal chandeliers so vast they seemed capable of anchoring a ship. The details were extravagant: gilded trim, lush red carpets, intricate plaster ceilings, and elegant European-style furnishings. The hotel boasted multiple restaurants, grand banquet halls, a stylish bar, and an outdoor pool with views of the ocean and the imposing Mount Hachijo-Fuji. It was the epitome of luxury. In its prime, it was the place to be. Wealthy Tokyoites would fly in for weekend escapes, corporations held lavish events in its ballrooms, and couples married in its chapel, feeling like royalty for a day. The hotel was the physical embodiment of the Bubble’s promise: boundless prosperity and a life of refined leisure.

The Slow Descent into Silence

But the dream was short-lived. The hotel opened just as the bubble began to burst. The stock market crashed, the economy plunged into a prolonged decline known later as the ‘Lost Decades,’ and the extravagant spending of the ’80s vanished. For a time, the Hachijo Royal struggled to stay afloat. It rebranded as the Hachijo Oriental Resort, attempting to attract new customers. However, the world had shifted. The kind of over-the-top, formal luxury it offered was going out of style. Travel trends moved toward simpler, more authentic experiences. Plus, running a massive hotel like this on a remote island, with enormous maintenance and staffing costs, became an unbearable load. Visitors to Hachijojima dwindled. The hotel limped through the ’90s and into the early 2000s, a mere shadow of its former glory, until finally, around 2006, the lights went out for good. The doors locked, and the palace fell silent.

Echoes in the Halls: The Haikyo Experience

Today, the Hachijo Royal Hotel stands as a breathtaking ruin. Perched on a hill overlooking the sea, its white facade is slowly stained and weathered by salty air and subtropical rain. From a distance, it still looks grand, but up close, decay is unmistakable. Nature is quietly reclaiming it. Vines crawl up walls and through broken windows. What were once manicured gardens have transformed into wild jungle. The true magic lies inside, as documented by urban explorers. Their photos and videos tell a powerful story. The grand lobby is the centerpiece: red carpets are faded and blanketed in dust and fallen plaster. The fountain is bone dry, clogged with debris. Yet the majestic structure endures. The twin staircases sweep upward into shadows. Light filters through a grimy glass ceiling, creating ethereal beams that illuminate dust particles swirling in the air. In the main lounge, a grand piano sits silent, its keys yellowed, forever awaiting a player who will never come. Banquet halls are cluttered with stacked chairs and tables, as if prepared for a ghostly celebration. In guest rooms, old boxy televisions, faded floral bedspreads, and peeling wallpaper curl in long strips. The outdoor pool offers perhaps the most iconic image: bright blue tiles visible beneath layers of green, scummy rainwater, and a carpet of moss and weeds. It’s a poignant snapshot of a man-made paradise reclaimed by nature. Exploring the stories of this place, even from afar, is a profound experience. It’s not only about decay; it’s about the stubborn endurance of beauty. The grandeur remains beneath the grime. It’s a quiet, melancholic site that speaks volumes about ambition, failure, and the relentless march of time. It’s king for a reason. Its atmosphere is incomparable.

Case File 02: Western Village – Where Animatronic Cowboys Never Die

Alright, let’s leave the French palace behind and venture inland to the mountains of Tochigi Prefecture, close to the well-known shrines of Nikko. Here, we encounter a vastly different Bubble-Era fantasy and, frankly, one of the creepiest and most fascinating haikyo in all of Japan: Western Village.

Howdy, Partner: America in the Tochigi Mountains

Where the Hachijo Royal embodied European elegance, Western Village embraced American ruggedness. Opened in 1975 and greatly expanded during the Bubble Era, this was more than a hotel—it was a lavish, high-budget theme park inspired by the American Old West. Picture a Hollywood movie set come alive in the heart of the Japanese countryside. It featured a main street with a saloon, sheriff’s office, blacksmith, and general store. Visitors could watch live-action cowboy shootouts, ride horses, pan for “gold,” and enjoy oversized American-style steaks. For Japanese families in the ’80s and ’90s, it was a wildly popular day trip—a fantasy escape to a mythical version of America. It was pure escapism, and during the bubble, the park’s owners poured enormous resources into expanding and enhancing it.

The High-Tech Core of the Old West

The park’s signature feature, which cemented its legendary haikyo status, was its fascination with animatronics. The owner, an avid fan, invested millions of yen in creating life-sized, eerily realistic robotic figures to populate the park. The centerpiece was the ‘Western Show,’ a large indoor attraction featuring a cast of animatronic cowboys, saloon girls, and outlaws performing a dramatic scene. The craftsmanship was exceptional for the era. Rumors persist that the creators had links to Disney’s Imagineering team, and the complexity of the figures certainly supports that theory. These animatronics didn’t just move their arms; they displayed intricate facial expressions, simulated breathing, and their movements were perfectly timed to a dramatic soundtrack. The park also featured a one-fifth scale replica of Mount Rushmore, oddly equipped with a slide. There was a ‘Western River’ boat ride passing scenes with animatronic Native Americans and wildlife. Adding to the bizarre charm, a ‘Mexico Park’ section included its own animatronic show. Most famously unsettling was an animatronic Clint Eastwood greeting visitors at the entrance to a main attraction—a high-tech tribute to American cultural influence, seen through a Japanese perspective.

Sunset on the Village

Its decline follows a familiar pattern. As the 2000s progressed, visitor numbers dropped, and the park’s nostalgic charm began to feel outdated. The costs of maintaining the elaborate animatronics soared. Burdened by debts, Western Village shuttered its gates permanently in 2007. But here’s where the story takes a strange turn. Instead of liquidating assets, the owner apparently just walked away—leaving everything behind. Costumes, props, souvenirs, and most hauntingly, all the animatronic figures. Cowboys, showgirls, sheriffs, and Clint Eastwood himself were abandoned, frozen in time.

A Truly Haunted Atmosphere: The Ruins Today

If the Hachijo Royal exudes melancholy and beauty, Western Village is unquestionably eerie and unsettling. It’s a haikyo that leaves a unique impression. Photos taken inside the abandoned park are nightmarish and legendary online. The main street is overrun, with weeds sprouting through the fake dirt. The buildings remain, their painted signs faded by the sun. But it is the animatronics that give the place its distinct creepiness. Inside the saloon, the robotic bartender slumps over the bar, plastic skin peeling and covered in thick dust. Showgirls on stage are frozen mid-kick, their frilly dresses torn and grey. In the main show, animatronic cowboys are captured in final poses—one drawing his gun, another collapsing ‘dead’ at a poker table. Their cracked, grimy silicone faces and glassy eyes stare blankly into darkness. This is the uncanny valley at its darkest and deepest. They appear almost human, but decay and stillness warp them into something monstrous. The infamous Clint Eastwood figure became an icon in the haikyo community, silently sitting in his chair, face slowly melting like a corpse. The site oozes a potent, cursed energy. It is a playground of forgotten joy twisted into something incredibly eerie and disturbing. Though most of the site has been demolished in recent years, its legend endures as a prime example of how the Bubble Era’s high-tech dreams could devolve into a uniquely modern horror story.

Case File 03: Sports World Izunagaoka – The Drowned Leisureplex

For our final case file, we journey to the Izu Peninsula in Shizuoka Prefecture. This region has long been a favorite getaway for Tokyo residents seeking a quick retreat, renowned for its stunning coastlines and, most notably, its hot springs (onsen). It was a natural choice for a Bubble-Era mega-resort, with Sports World Izunagaoka standing out as one of the most ambitious projects.

Izu Peninsula: Tokyo’s Nearby Escape

To understand why Sports World was established here, you need to know Izu. This claw-shaped landmass extends into the Pacific, just a few hours by train from Tokyo. It’s dotted with onsen towns, ryokans (traditional inns), and beaches. For decades, it has served as the capital’s backyard playground. So, during the bubble era, developers saw Izu and thought, ‘Let’s create the ultimate recreational spot here.’ Their goal was to build an all-encompassing destination offering every type of entertainment imaginable.

A Playground of Leisure: The Concept

Sports World Izunagaoka was more than just a hotel or water park. It was a “leisure land,” a vast complex designed to fulfill every desire. The highlight was a massive, futuristic dome housing a cutting-edge indoor water park called “Jungle Pool.” This was no ordinary swimming spot. It featured a huge wave pool capable of generating powerful waves, towering water slides weaving throughout the building, and a tropical theme complete with artificial palm trees and rocks. The concept was to provide a summer beach atmosphere any day of the year, regardless of weather. But that was only the beginning. The resort also included a 100-lane bowling alley—one of Japan’s largest—onsen facilities with multiple baths, a hotel, plus restaurants and game arcades. It was a self-contained bubble of amusement. Visitors could check in on a Friday and remain on site until Sunday, spending their time swimming, bowling, soaking in the onsen, and dining. It epitomized the Bubble Era’s “all-inclusive” leisure fantasy, built to accommodate vast numbers of guests with maximum fun and efficiency.

When the Bubble Burst, the Pool Emptied

The tragedy of Sports World lies in its timing. Construction finished in 1993, well after the bubble had burst in 1991. The project was born out of the bubble’s optimism but launched into the harsh reality of its collapse. It was like a grand ship setting sail directly into a storm. From day one, the resort struggled. The massive crowds it anticipated never arrived. People cut back on expenses, and extravagant weekend trips were among the first sacrifices. Running the enormous complex demanded enormous costs. Heating the giant dome and powering the wave pool were extremely expensive. After only a few years of an uphill fight, Sports World Izunagaoka closed permanently in 1997. It was a dramatic failure, a testament to unfortunate timing.

Nature Takes Back: The Green and the Blue

As a haikyo (ruined place), Sports World is remembered for one haunting and symbolic image: the flooded Jungle Pool. Because the colossal glass dome remained intact, rainwater gradually accumulated inside over the years, slowly filling the empty wave pool. Without filtration or chemicals, nature reclaimed it. The water turned a murky green, with thick growths of algae, reeds, and other plants transforming the pool into a strange, enclosed swamp. Photos from its peak decay are striking. The bright blue and yellow water slides—symbols of excitement and movement—stand quietly, coated in moss and ending abruptly in a primordial green broth. The artificial palm trees and rocks resemble relics from a forgotten civilization, half-submerged in stagnant water. It’s a powerful image: a man-made ocean, a controlled space of manufactured fun, effortlessly overtaken and consumed by nature. The rest of the complex tells a similar tale. The 100-lane bowling alley rests in dusty silence, pins still standing on some lanes, awaiting a final strike that will never come. The hotel rooms decay, and the onsen baths are dry and cracked. Sports World Izunagaoka serves as a poignant example of how swiftly and completely nature can erase our grandest creations. It remains a silent, swampy monument to a dream that sank.

Beyond the Trespass Tape: The Soul of Haikyo

So why do we, along with many others, become so captivated by these places? It’s not merely about admiring cool, old buildings. The fascination goes much deeper. Behind haikyo exploration lies a whole philosophy and culture connected to some fundamental aspects of the Japanese mindset. It’s about more than just excitement; it’s about discovering meaning within the ruins.

Mono no Aware: The Beauty of Things Fading

There is a Japanese concept called ‘mono no aware’ that’s somewhat difficult to translate directly. It’s a gentle, bittersweet sadness about the fleeting nature of life. It’s the feeling you experience in spring when you see cherry blossoms, knowing their perfect beauty will only last a few days. It is an awareness of impermanence and the poignancy of things passing away. Haikyo embodies mono no aware on a grand, concrete scale. These Bubble-Era resorts are like enormous cherry trees—briefly flourishing with life and luxury, now slowly and gracefully decaying. There is great beauty in that. Seeing a grand piano coated in dust or a swimming pool reclaimed by the forest isn’t just eerie; it’s deeply moving. It reminds us that everything, no matter how large, strong, or costly, eventually returns to the earth. It’s a nostalgia for a past we never lived through and a profound meditation on time itself. It’s not about glorifying destruction but about valuing the full life cycle of a place, including its end.

The Unspoken Rules of the Game

It’s vital to be clear on this point. The haikyo community, both in Japan and around the world, follows a strict code of ethics. The top rule is the urban explorer’s mantra: ‘Take only pictures, leave only footprints.’ This is essential. True explorers are like shadows; they observe and document without disturbing anything. They don’t vandalize, break things, or steal souvenirs. The aim is to preserve the site exactly as it was found, out of respect for its history and for the next visitor. It’s also important to remember that nearly all of these locations are private property. Entering them is trespassing and can be hazardous. Floors may be weak, structures unstable, and dangers unseen. Respect is crucial—these places are not playgrounds. The genuine spirit of haikyo is appreciation, not destruction or reckless thrill-seeking. It’s about silently witnessing a story that continues to unfold.

The Ghosts in the Machine: What These Ruins Tell Us

In the end, these ruins are more than just photo backdrops. They are tangible history lessons. They are the ghosts in Japan’s modern economic machine, telling the tale of a nation’s immense ambition, boundless confidence, and the harsh aftermath of a grand celebration. Walking through the halls of Hachijo Royal or seeing the sagging animatronics of Western Village lets you feel the weight of the ‘Lost Decades.’ These are not just architectural failures; they are the memorials of a future Japan planned but never realized. They stand as a powerful, silent caution about the perils of unchecked speculation and the fragility of economic booms. Yet, they also embody the dreams of thousands—the architects who designed them, the workers who built them, and the guests who sought escape. In their silence, these ruins tell profound stories, offering a richer, more emotional connection to the past than any museum exhibit could.

The Future of the Past

What will become of these concrete giants now? Their story continues to unfold. The fate of most haikyo is a slow, ongoing dance with demolition. For years, Western Village stood as a creepy mecca for explorers, but in 2020, the wrecking balls finally arrived. The animatronic cowboys have most likely met their final end. The cost of tearing down these massive structures is enormous, which often explains why they remain standing for so long. The owners might be bankrupt, or ownership itself may be tangled in a legal mess. Thus, many of them will continue their gradual transformation, becoming less like buildings and more like part of the natural landscape—modern ruins for future generations to contemplate.

Occasionally, there are stories of redevelopment, but for resorts of this scale, such cases are extremely rare. The expense of renovating and bringing them up to modern safety standards is often higher than starting fresh with new construction. So, most remain in a state of limbo. They are waiting—waiting for a final decision, waiting for inevitable collapse, or simply waiting for the forest to finish its meal. Their future is uncertain, which only adds to their mystique. They exist outside the usual cycle of construction and destruction, occupying a liminal space between past and present.

So, there you have it—a glimpse into the strange and beautiful world of Japan’s Bubble-Era haikyo. These sites are a unique and powerful part of the Japanese landscape, hiding in plain sight. They are remnants of a time when it felt like the sky was the limit and the party would never end. They remind us that even the biggest dreams can fade, but they leave behind some truly incredible ghosts. Listening to the stories those ghosts tell is a journey in itself. So next time you find yourself exploring the backroads of Japan, keep your eyes peeled. You never know when you might glimpse a forgotten palace or a silent, watchful Ferris wheel, haunting the good times. Seriously, these places hold a history that is both epic and intimate. They stand as a testament to a wild era and a quiet reminder that nothing lasts forever—and there is a deep, profound beauty in that. Catch you on the flip side. Peace.