Yo, what’s up. Taro Kobayashi here. So you’ve been scrolling the ‘gram, maybe binge-watching some anime, or even dropped into Japan for a quick trip. You’ve seen it, for sure. That iconic wooden strip, that porch-like thing that seems to be neither inside nor outside, usually looking out onto a perfectly manicured garden. You see characters in shows just chilling there, feet dangling, sipping on some tea, staring at the rain. It looks peak aesthetic, a level of calm you can only dream of. And you’re probably thinking, “Okay, what’s the deal with that? Is it just a porch? Why does it look so… important?”

Bet. You’ve hit on something that’s low-key one of the biggest keys to understanding the Japanese mindset about home, nature, and community. That space has a name: the engawa (縁側). And nah, it’s not just a porch or a veranda. Calling it that is like calling a katana just a sword. You’re not wrong, but you’re missing the whole backstory, the cultural sauce, the vibe. The engawa is an architectural mood. It’s a physical representation of the gray area, the in-between, a concept Japan is kinda obsessed with. It’s the architectural embodiment of “it’s complicated.” It’s a space designed for chilling, for connecting, for just… being. But why did it even become a thing? It’s not just for looks. It’s a genius-level response to Japan’s wild climate, a stage for its social life, and a window into its soul. So, let’s spill the tea on the engawa and figure out why this simple strip of wood is actually a masterclass in living with nature, not against it.

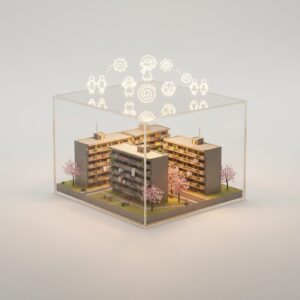

To see how this philosophy of communal living and connection to environment evolved in modern times, check out the story of Japan’s iconic danchi housing complexes.

What Even IS an Engawa? The Deets

Alright, before diving into the deep-cut philosophy, let’s start with the basics. What exactly are we looking at? At its core, the engawa is a strip of flooring, almost always polished wood, that runs along the outside of a traditional Japanese house. It’s under the same roof, sheltered by deep eaves, yet it lies outside the main paper screens or walls of the room. It serves as the ultimate transitional space. Think of it as the gradient between your house’s boundary and the garden beyond.

But there’s more nuance to it. There are layers to this concept. Two primary types of engawa exist, and the distinction is subtle but significant. It all depends on how it’s constructed in relation to the house.

First, there’s the kure-en (くれ縁). This is essentially an extension of the room’s floor. The wooden planks are part of the main house structure, running parallel to the room they border. It feels like an open-air continuation of the room itself. When you slide open the shoji (the paper screen doors), the room simply flows out into this wooden space. It feels integrated, deliberately designed from the outset. It offers a seamless transition, blurring the line between inside and outside.

Then there’s the nure-en (濡れ縁), which literally means “wet veranda.” This type is more exposed to the elements. Often a separate structure attached to the outside of the house, its planks may run perpendicular to the wall. Because it’s more ‘outside,’ it’s built to handle rain and weather. The wood may be sturdier, with gaps between the planks for drainage. This type feels more like a dedicated outdoor platform, akin to a dock attached to your home. It remains under the eaves but has a rougher, more practical feel. It’s where you’d leave your garden sandals or wash your feet before stepping fully inside.

Beyond these two main types, there’s a wide range of variation. You might find a simple, narrow engawa barely wide enough to walk on, called an enobuchi (縁框). Alternatively, there can be a very wide one, more similar to a full deck, sometimes known as a hirobiro-en (広々縁), literally a “spacious engawa.” Sometimes these wrap around the entire house, creating a 360-degree walkway; other times, they face only the main garden, acting as a stage to showcase the best views.

The material is almost always wood, which is essential for that classic feel. The sensation of warm, sun-baked wood beneath your feet or hands is integral to the experience. The type of wood matters as well. Cypress (hinoki), cedar (sugi), and pine (matsu) are traditional choices. They’re durable, aromatic, and over time develop a beautiful silvery-grey patina. The craftsmanship is exceptional. The planks fit together with incredible precision, polished smooth to a gleaming finish. This isn’t a makeshift deck from a hardware store; it’s a piece of furniture crafted for the exterior of your home.

So, the engawa isn’t just a random add-on. It’s a carefully considered architectural feature with its own language and typologies. It’s the buffer zone, the airlock—a space that belongs to both the house and the garden, yet fully to neither. This very ambiguity is its strength. It’s this in-betweenness that allowed it to address many of Japan’s unique challenges, from its harsh climate to its complex social customs. A design born out of necessity, but elevated into an art form.

The OG Climate Control: Surviving Japan’s Weather

So, why go to all this effort? Why construct such an elaborate indoor-outdoor space? The answer, fam, begins with the weather. If you’ve never experienced a Japanese summer, you can’t truly capture the vibe. It’s on an entirely different level of hot and sticky. We’re not talking about a pleasant, sunny warmth; we’re talking mushi-atsui (蒸し暑い) — a steamy, suffocating humidity that feels like you’re wrapped in a hot, wet towel. The air is thick. You sweat just by existing. It’s relentless. Before air conditioning, enduring this was the single greatest architectural challenge.

Enter the engawa, a stroke of pure, unfiltered genius. It’s part of a brilliant, passive climate control system that Japanese houses refined over centuries. Let’s unpack this original green technology.

The main objective in a Japanese summer is to achieve kazetōshi (風通し), or cross-ventilation. You have to get the air flowing, no matter what. A traditional Japanese house is designed to be deconstructed. The inner walls aren’t solid brick and plaster; they’re lightweight sliding screens. There’s the shoji, the iconic screens with translucent washi paper that allow soft, diffused light in, and the fusuma, opaque and often beautifully painted paper screens used as room dividers. In summer, you can literally remove them. You open all the shoji facing the engawa, and take out some fusuma inside. Instantly, your series of small, boxy rooms becomes one large, open space. The breeze passes straight through the house, creating a natural wind tunnel.

The engawa is the critical intake and exhaust point for this system. It creates a shaded, cool zone around the house. Though the sun beats down on the roof, the deep eaves, called hisashi (庇), extend far out, keeping the engawa and house sides in shadow. This is crucial. Direct sunlight never reaches the walls or interior during the hottest part of the day. The air on the engawa stays cooler than the sunny garden air. This temperature difference generates a natural convection current, drawing cooler air from the shaded engawa into the house and pushing hotter air out the other side. It’s subtle but profoundly effective.

Check this out: the design is seasonally smart. In summer, the sun is high in the sky, and the deep eaves are perfectly angled to block that high-angle sun. But in winter, the sun is lower in the sky, and the eaves allow that low-angle sunlight to stream in, crossing the engawa and deep into the rooms, passively warming the house. The engawa floor, dark polished wood, absorbs winter sunlight, storing and radiating heat back inside. It’s essentially a built-in seasonal solar heater.

There’s more. The engawa also helps handle Japan’s other major weather event: rain. Japan has a rainy season, tsuyu (梅雨), and typhoons. It can rain hard. The engawa serves as a protective buffer. Rain may strike the edge of the engawa, but the delicate, paper-made shoji screens are recessed and stay dry. This lets you keep the house open for ventilation even during rain, as long as the wind isn’t blowing it sideways. You can sit inside, shoji wide open, and watch the rain fall just feet away in the garden without getting wet. The sound of rain hitting the garden from the safety of the engawa is an iconic sensory experience in Japan—a whole mood in itself.

This entire system is a masterclass in working with the environment rather than against it. Modern Western houses often act like sealed boxes, fortresses against the elements. You crank up the AC in summer and the heat in winter to create an artificial, stable indoor climate. Traditional Japanese houses, with the engawa at their core, are the opposite. They’re porous. They breathe. They accept that the outside will come in, and cleverly manage that interaction—filtering light, guiding breeze, framing the view. The engawa isn’t merely a feature; it’s the interface between human living spaces and nature. It’s the ultimate hack for comfortable living in a climate that can be, to put it mildly, pretty extreme.

A Social Platform Before Social Media

The engawa is a climate-control marvel. No doubt. But that’s only part of its story. Its equally important role is as a social device—a stage for community, a venue for the small interactions that shape daily life. To understand why, you need to grasp a key concept in Japanese culture: uchi-soto (内 Soto).

Uchi-soto roughly means “inside/outside,” but it’s much more nuanced. It describes the Japanese cultural practice of categorizing people into in-groups (uchi) and out-groups (soto). Your family and close coworkers represent uchi. Strangers, people from other companies, your mail carrier—that’s soto. The rules of communication and etiquette differ drastically depending on which group you’re engaging with. With uchi, you can be relaxed, direct, and casual. With soto, you must be formal, polite, and indirect. This system isn’t about friendliness or hostility; it’s about preserving social harmony (wa, 和) through clear, widely understood boundaries.

This social norm is embedded in home architecture. The home embodies the ultimate uchi space. Being invited inside is significant; you don’t just drop in casually. First, there’s the genkan, the entry where you remove your shoes. Crossing from the genkan into the main house marks an important boundary. You’re entering someone’s private, uchi world. But what if you want a conversation that’s more than a call from the street but less formal than an indoor visit?

That’s where the engawa comes in. The engawa occupies the perfect uchi-soto middle ground. It’s physically part of the house but lies outside the shoji screens. It’s neither fully soto (the street or garden) nor fully uchi (the interior). It’s an ideal, socially calibrated neutral zone.

Imagine a neighbor stopping by with some garden vegetables. They don’t need to enter the house—instead, they step onto the engawa. The homeowner opens the shoji and sits on the tatami floor, while the neighbor sits on the edge of the engawa. Here, they can chat comfortably without removing shoes or going through formalities (though tea is often served). It’s casual, spontaneous, and perfectly respects the uchi-soto boundary. The engawa enables connection without demanding intimacy. It acts as a social airlock.

This space became the heart of informal community life, the neighborhood’s open-air chatroom. Kids would play along its length. On warm summer evenings, families gathered on the engawa to cool off, enjoy watermelon, and watch fireflies. It was a place for yūsuzumi (夕涼み), the cherished tradition of savoring summer’s evening coolness. Grandparents could sit there, observing the world and exchanging friendly nods with passersby. It offered a front-row view of neighborhood life.

This function also shifts perspectives on privacy. In the West, a front porch faces the street and is public-facing, while the backyard, often fenced, is private. In many traditional Japanese homes, this is reversed. The engawa typically faces a private garden enclosed by walls or fences. The focus isn’t on presenting to the street but on crafting a semi-private space for interaction with a chosen community—neighbors who access the side of the house. It’s a more curated and controlled social setting.

Consider the sensory experience: you’re separated not by a doorbell and door, but by a paper screen. You hear your neighbors’ lives, and they hear yours. The engawa fosters a gentle, ambient awareness of each other—a continuous, low-level connection forming the foundation of a close-knit community.

So the engawa isn’t just a clever climate design. It’s an ingenious act of social engineering—a physical solution to the delicate etiquette of uchi-soto. It offers a crucial middle ground, a space neither formal nor informal, neither public nor private. It supported a fluid, effortless flow of communication that built and sustained communal bonds for centuries. It was the original social network, crafted from wood and tradition.

The Art of Blurring Lines: Engawa and the Japanese View of Nature

We’ve already looked at the practical aspects—climate and community. But now it’s time to dive into the deeper elements, the philosophy. Because the engawa is much more than a functional feature. It embodies a fundamental Japanese aesthetic and spiritual belief: that humans are not separate from nature, but an integral part of it. The aim isn’t to dominate nature, but to coexist harmoniously with it. The engawa serves as the architectural expression of that harmony.

In Western traditional architecture, a house is often seen as a fortress against nature. Thick walls, historically small windows, create a controlled interior world, while outside lies the untamed wilderness. Nature is something you look at through a window like a framed picture. In contrast, the Japanese perspective, exemplified by the engawa, works to dissolve this divide. The goal is not to observe the garden from afar but to feel immersed in it, even when indoors.

This ties into the design of house and garden as a single entity. A traditional Japanese garden is not merely a collection of plants. It’s a carefully orchestrated, idealized landscape. Every stone, tree, and patch of moss is placed with artistic purpose. The engawa is crafted to be the ideal platform to view this artistry. When sitting on the tatami inside and the shoji screens are open, the heights of the room’s floor, the engawa’s wood, and the garden ground align closely. The visual transition is fluid. The engawa bridges the inside and outside, inviting the garden to feel like a natural extension of the room.

This connects to the concept of shakkei (借景), or “borrowed scenery.” This advanced gardening technique integrates elements from beyond the garden’s boundaries—such as a distant mountain or tree cluster—into the composition, making the garden feel larger and more expansive. The engawa facilitates this “borrowing.” From it, your gaze follows the garden elements outward to the borrowed scenery, blending moss beneath your feet and a horizon mountain into a single, continuous scene. You sit on the edge of a vast, living artwork.

This yearning for unity with nature has its roots in Shinto, Japan’s indigenous religion. Shintoism is animistic, holding that gods or spirits, kami (神), inhabit natural entities like mountains, rivers, ancient trees, or uniquely shaped rocks. Nature is sacred. Bringing nature’s essence into the home means bringing yourself closer to the divine. By breaking down the barrier between house and garden, the engawa becomes a deeply spiritual space—a place for quiet reflection on the changing seasons, a key theme in Japanese art and culture. The vivid green of early summer, the cicadas’ calls, the fiery autumn maples, the silent snowfall—all are intimately experienced from the engawa. It grants a front-row seat to nature’s slow, beautiful, and often bittersweet rhythm, known as mono no aware (物の哀れ).

Now, consider the experience, the vibe. Sitting on an engawa engages all your senses. You feel the texture of weathered wood. You smell damp earth after rain or the fragrance of daphne blossoms in spring. You hear insects chirping, frogs croaking, bamboo leaves rustling in the breeze. This sensory immersion is the essence of the space. It acts as a form of meditation, urging you to slow down, to focus, to live fully in the present moment.

The architecture itself fosters this experience. Low eaves create a horizontal frame, guiding your gaze toward the garden. Upright posts establish vertical frames. You’re constantly viewing the natural world through these gentle, human-made frames—not separated by a window, but composed by a frame that enhances your appreciation of the inherent beauty. The openness, the flow of air, the connection to the earth—all contribute to a profound sense of peace and belonging. You’re not merely a visitor in nature; you’re an active participant. The house and garden are in conversation, with you, seated on the engawa, at the heart of that dialogue.

That’s why calling it just a “porch” feels inadequate. A porch is an add-on. The engawa is a vital element of a holistic system designed to unify art, architecture, and nature into one harmonious living experience. It reflects a deep philosophical dedication to living in rhythm with the natural world. It’s a vibe that, once felt, stays with you forever.

The Engawa’s Glow-Up and Ghosting: Modern Japan’s Relationship with its Porch

The engawa is an incredible, multi-functional piece of architectural brilliance—a climate solution, a social gathering place, and a philosophical symbol all rolled into one. You might assume, “Cool, so every house in Japan must have one, right?” But that’s where reality hits. Walk through a modern Japanese suburb, and you’ll see many houses that appear quite ordinary—Western-style homes, boxy modern designs, and numerous apartment buildings. The classic, sweeping engawa has become a rare sight. So, what happened? Why did Japan start abandoning its most iconic architectural feature?

The decline of the engawa mirrors Japan’s rapid modernization throughout the 20th century. After World War II, Japan experienced an economic boom. Cities expanded rapidly, and people migrated from rural areas to urban centers in search of work, shifting architectural priorities significantly.

Firstly, space turned into the ultimate luxury. In densely populated cities like Tokyo and Osaka, land prices skyrocketed. Houses were squeezed onto tiny plots, making the traditional model of a home with a spacious garden impractical. Homes were built right up to lot boundaries, leaving just enough room to move around, scarcely accommodating a garden or a wide engawa. Since an engawa requires a view, without a garden, it loses its essential purpose. Staring at a neighbor’s concrete wall just a few feet away doesn’t evoke the same Zen feeling.

Secondly, lifestyles shifted. The rise of cars and mass transit made neighborhoods less walkable and self-contained. The tightly knit communities where everyone knew one another began to unravel. People no longer casually stopped by a neighbor’s engawa for a chat. Life grew more private and fragmented. The engawa’s social function was replaced by phone calls, cafes, and eventually the internet. Concerns about privacy and security increased, making the once open and accessible house design feel unsafe to some. Solid walls, lockable glass doors, and clearer separations from the outside world became preferred.

Then came the game-changer: air conditioning. The engawa and its passive ventilation system were designed to make unbearable summers tolerable. But AC made those summers comfortable. With the push of a button, people could enjoy a cool, controlled indoor environment. Why bother opening and closing screens and enduring the summer heat when you could escape it altogether? This technological fix, as often happens, won out over the elegant traditional solution. The need for strong cross-ventilation vanished, along with the architectural elements that supported it.

Westernization also played a significant role. As Japan embraced Western notions of modernity, it adopted Western living styles. Chairs and tables replaced sitting on tatami mats, and clearly defined rooms (dining rooms, living rooms) replaced the flexible, open-plan spaces of traditional homes. The engawa, designed to be appreciated from the low vantage point of someone seated on the floor, doesn’t harmonize well with a furniture-filled, Western-style living room. The seamless connection breaks when you look down at the garden from a high chair through a glass window.

Thus, the engawa came to be viewed as a relic of a bygone lifestyle—beautiful, yes, but seen as impractical for modern living, a luxury requiring too much space, too much upkeep, and a community structure that no longer existed. It was a casualty of Japan’s rapid economic growth and modernization.

But the story doesn’t end there. Recently, there’s been a remarkable resurgence of interest in the engawa. People are beginning to recognize what was lost. A “back to the land” movement is gaining momentum, along with renewed appreciation for traditional craftsmanship and a desire for a slower, more connected life. Architects are finding inventive ways to incorporate the concept of the engawa into modern homes. While it may no longer be a traditional wooden platform, it might take the form of a deep covered balcony, a living room with floor-to-ceiling sliding glass doors opening onto a small courtyard, or what’s called a “wood deck terrace.” These designs aim to recapture the blurred boundaries and connection to the outdoors.

Moreover, old traditional houses, or kominka (古民家), are being preserved rather than demolished. They have been transformed into trendy cafes, boutique hotels, and guesthouses, where the engawa remains the most prized feature—the spot everyone wants to sit and the most Instagram-worthy element. What was once considered old-fashioned has now become the height of cool. The engawa has experienced a renaissance, a testament to the enduring power of its design. Even in the age of air conditioning and the internet, the simple, profound joy of sitting on a wooden platform, feeling the breeze, and gazing at a garden is increasingly sought after.

Hunting for the Vibe: Where to Experience a Real Engawa Today

Alright, so you’re convinced. You understand the hype. You want to experience this ultimate chill for yourself. But since they’re no longer on every corner, where can you actually find a genuine engawa? This isn’t about ticking off tourist spots. It’s about discovering the right atmosphere to truly grasp the feeling of the engawa. You’re chasing a vibe, not just another photo.

Your best options fall into a few categories: temples, traditional inns (ryokan), restored old houses (kominka), and gardens. Each offers its own unique take on the engawa experience.

First, Zen temples, especially in places like Kyoto or Kamakura, are treasure troves for engawa. These temples were designed for contemplation, with the engawa serving as the main tool for that purpose. Imagine yourself at Ryōan-ji in Kyoto, renowned for its rock garden. You don’t walk through the garden—you sit on the wide, dark, polished engawa of the main hall and simply… observe. Though surrounded by many others, silence prevails. Everyone focuses on the mysterious arrangement of rocks and raked gravel. Here, the engawa acts as a meditation bench, compelling stillness. You sense the history in the smooth, worn wood beneath your hands, wood polished by monks and visitors over centuries. It’s a deeply spiritual, powerful experience.

Next, staying at a traditional ryokan offers perhaps the most immersive way to experience the engawa as it was meant to be—a part of home life. A good ryokan will have rooms opening onto a shared or private engawa overlooking a beautiful garden. This is your fantasy come to life. In the morning, you slide open the shoji screens, step out onto the cool wood in your yukata (a light cotton robe), and sip green tea while the garden stirs awake. In the evening, you relax there after a hot bath, feeling the cool night air. Here, the engawa connects you to daily rhythms. It’s more than a viewing platform; it’s your personal chill zone. It links you to the seasons and the flow of the day in a way no sealed hotel room ever could.

Then there’s the modern twist: the kominka cafe. Across rural Japan and even hidden city neighborhoods, people are buying beautiful old farmhouses and merchant homes and transforming them into stylish cafes and restaurants. These almost always put the engawa front and center. You can order craft coffee and cake, then sit on the sunlit engawa with your feet dangling over the edge, gazing out at rice paddies or a small garden. This is the engawa’s social, community role revived. You’ll see friends chatting, couples unwinding, people engrossed in books. It’s the historic function of the engawa—casual socializing in a beautiful semi-outdoor space—brought into the 21st century. It’s proof the vibe is timeless.

Finally, public gardens and historic homes converted into museums are excellent choices. Places like Kenrokuen in Kanazawa, the Adachi Museum of Art with its celebrated gardens, or Sankeien Garden in Yokohama all feature historic buildings with stunning engawa you can often sit on. They offer the most grand and “artistic” version of the experience. With perfectly manicured gardens, breathtaking views, and engawa masterpieces of carpentry, this is where you can best appreciate the concept of shakkei—using the engawa as a frame for living art. It’s less personal than a ryokan, but an incredible way to admire the aesthetic ideals behind the design.

When you find your spot, don’t just snap a photo and leave. Take off your shoes. Sit down. Place your feet on the wood. Feel the temperature. Listen. Watch how the light shifts. Stay awhile. The magic of the engawa doesn’t come instantly. It’s a slow-release vibe. In quiet moments, you finally realize—that simple strip of wood is a gateway to another way of seeing, a calmer way of being.

More Than a Porch, It’s a Worldview

So, we’ve explored in depth. From the intricate details of nure-en versus kure-en to the profound philosophy behind shakkei and uchi-soto. By now, it should be evident. That wooden porch you see in photos is far more than just a porch. It’s a response. It’s an answer to the enduring questions Japan has faced: How do you live comfortably in a climate that is both stunning and harsh? How do you nurture community while upholding strict social boundaries? How do you construct a home that doesn’t isolate you from the natural world you revere?

The engawa is the elegant, seemingly simple solution to all of these challenges. It functions as a climate control system. It acts as a social connector. It serves as a place for meditation. It represents the ultimate in-between space, and its strength lies in this ambiguity. It imparts a lesson that feels increasingly relevant in our hyper-connected yet oddly disconnected world—a lesson about the significance of the spaces in between: the pause, the transition, the gray area.

This design invites you to slow down, be present, and observe the world around you. It stands as a quiet defiance against the sealed, climate-controlled, indoor-focused lifestyle. Admittedly, you won’t find an engawa on every modern Japanese home, and the lifestyle it embodies has diminished. Yet the idea of the engawa, its essential spirit, is experiencing a revival. It acknowledges that traditional ways held some remarkably effective strategies for living well.

Next time you spot one—whether in an anime, a temple in Kyoto, or a trendy countryside café—you’ll understand what you’re seeing. It’s not merely an attractive architectural detail. It’s a fragment of cultural DNA. It’s an entire vibe. It’s the tangible embodiment of calm, a masterclass in design, and a reminder that sometimes the best way to engage with the outside world isn’t to build a thicker wall, but to create a beautiful space that invites it in.