You’ve seen it scrolling on your feed. Between the endless reels of ramen pulls and impossibly perfect cherry blossoms, you see something else. Something… different. A massive, sheer wall of silky smooth concrete. A stark, minimalist room where the only furniture is a single, perfectly placed chair and a sliver of window showing a solitary tree. You see a hotel that looks less like a vacation spot and more like the secret lair of a supervillain from a high-budget anime. And the caption is always something like “Pure bliss” or “Zen achieved.” And you’re just sitting there thinking, “For real? It looks kinda cold.” You wonder what the deal is. In a country celebrated for its warm wooden temples, intricate paper screens, and delicate garden aesthetics, why is there this major obsession with building luxury hotels that look like futuristic fortresses? It’s a total vibe mismatch, right? But that’s the thing about Japan. The minute you think you have it figured out, it hits you with a plot twist. This isn’t just an architectural trend; it’s a whole mood, a philosophical statement poured into concrete and rebar. It’s a deep-dive into a very specific type of Japanese luxury that’s less about fluffy bathrobes and more about clearing your mental cache. It’s about finding the sublime in the severe, the calm in the colossal. This is the lowdown on Japan’s concrete hotel scene—not just a list of where to stay, but the why behind this powerful, polarizing, and undeniably cool aesthetic. It’s time to get why these bunkers are considered the peak of chic.

To fully appreciate this aesthetic, it’s essential to understand the work of Tadao Ando, a master who transforms concrete into profound architectural poetry.

The Concrete Legacy: Tadao Ando and the Brutalist Glow-Up

To understand the significance, you need to know the name: Tadao Ando. He’s the undisputed genius, the ultimate figure in Japanese concrete architecture. If you encounter a building in Japan that feels like stepping into a minimalist art piece, chances are Ando’s name is behind it. But here’s the twist: he’s a self-taught architect and a former professional boxer. That’s not merely an interesting tidbit; it’s the essence of his story. His method isn’t academic; it’s instinctual. He battles with his materials, with light, and with the landscape itself to create something transcendent. This isn’t the Brutalism your grandfather recalls from 1960s London. Western Brutalism was often tied to post-war social housing projects, resulting in structures that could feel heavy, imposing, and sometimes downright oppressive. It emphasized raw, honest, and often publicly funded functionality. Ando’s concrete, however, is a completely different entity. It’s not Brutalism; it’s a form of architectural haiku. It’s painstakingly crafted, with a surface so smooth it resembles silk. The tie-holes left by the wooden forms are arranged in a flawless, rhythmic grid—a signature detail that transforms a construction mark into a decorative feature. This blend of raw strength and delicate precision defines his entire aesthetic.

The Philosophy Behind the Form

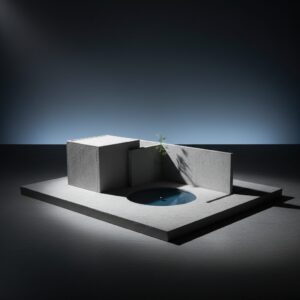

Why the obsession with concrete? It boils down to a few core ideas that are deeply Japanese at heart, yet reinterpreted for the modern age. Above all is the interplay between the harsh, man-made structure and the soft, ever-changing natural world. Ando’s buildings are meant to be vessels for light. A blank concrete wall becomes a cinematic screen, following the sun’s path from dawn to dusk. A narrow slit in the ceiling doesn’t just let in light; it carves a brilliant, moving line across the floor, compelling you to notice the passage of time. The concrete frames nature, encouraging you to appreciate a single bamboo stalk or a patch of sky more intensely than you would standing in an open field. It’s a contemporary take on the traditional concept of shakkei, or “borrowed scenery,” where a garden’s design incorporates the landscape beyond its boundaries. Here, the building itself borrows the sky, the rain, and the light, making them integral parts of the architecture.

Then there’s the connection to wabi-sabi, that quintessential Japanese aesthetic that finds beauty in imperfection, impermanence, and authenticity. At first glance, a flawless Ando concrete wall seems the opposite of imperfect. But consider it over time. The concrete stains with rain, its hue shifts with the seasons, and it develops a patina. It lives, breathes, and ages. It tells a story. This raw materiality is a deliberate rejection of the artificial, the plastic, the disposable. It’s a statement about embracing the authentic character of a material, imperfections included. The massive, thick walls also serve another critical purpose in a densely populated country like Japan: they create silence. Entering one of these structures from a noisy street is a full-body experience. The world’s noise just… ceases. The concrete insulates you, crafting an almost monastic sanctuary. It’s a deliberate meditation space, designed for introspection. This aligns with centuries of Zen Buddhist tradition, which values silence and simplicity as paths to enlightenment. These buildings aren’t just structures; they’re modern secular monasteries built for quiet contemplation.

Reading the Vibe: The Hotel as an Immersive Experience

Let’s be honest: these hotels dominate Instagram. Their aesthetics are simply too striking not to photograph. But viewing them only as stylish backdrops for your next profile picture misses the point entirely. The real highlight is the experience of staying in one of these places. It’s less about traditional customer service and more about allowing the space itself to be your host. The aim is to offer what might be called “Main Character Energy.” When you stroll down a long, echoing concrete hallway, lit only by a narrow beam of light from above, you’re not just a guest heading to your room—you’re the lead in a thoughtful indie film. The environment is so powerful and unique that it transports you to a different mindset. It invites you to slow down and notice details you’d usually overlook. The minimalist design acts as a tool for sensory recalibration. By removing the usual hotel room clutter—the loud patterns, generic artwork, unnecessary furniture—the space amplifies what remains. You become keenly aware of the concrete’s texture under your fingers, the subtle change in light as a cloud drifts by, the sound of your own breath. It’s a form of purposeful sensory deprivation that ultimately heightens your awareness rather than diminishing it. It’s an essential vibe check for your soul.

A New Kind of Luxury

This also marks an intriguing evolution of omotenashi, the celebrated Japanese tradition of hospitality. Classic omotenashi often involves anticipating every guest’s need, delivering attentive yet nearly invisible service that’s always one step ahead. It’s warm, personal, and exceptionally thoughtful. Hospitality in these concrete hotels offers a different experience. It’s the luxury of solitude. Service remains flawless but discreet to the point of near invisibility. Here, the ultimate luxury is the space itself: a perfectly tuned environment for quiet, solitude, and self-reflection. The hotel doesn’t try to entertain or pamper you; instead, it offers a stunning, powerful void and trusts you to fill it with your own inner resources. This is a bold, confident form of hospitality that says, “We’ve built the perfect stage; the rest of the performance is yours.” It represents a significant cultural shift from the collective mindset often linked to Japan. These spaces are designed for the individual, serving as sanctuaries for the self and offering a rare and precious gift in today’s world: a moment of deep, uninterrupted peace.

Case Study: Naoshima, The Art Island Concrete Mecca

To truly grasp the pinnacle of this aesthetic, you must visit Naoshima. This small island in the Seto Inland Sea is the spiritual birthplace of the concrete-and-art movement. It’s less a destination to visit and more an immersive experience—a comprehensive environmental art project conceived by the Benesse Corporation and brought to life, naturally, by Tadao Ando.

Benesse House: The Museum Where You Can Stay

This is the original—the place that started it all. Benesse House isn’t a hotel that features art; it’s a museum with guest rooms. It’s divided into several distinct sections, each offering a unique way to engage with the blend of art, architecture, and nature. The “Museum” area places you literally inside the gallery walls, allowing you to wander among works by artists such as Yves Klein and Cy Twombly late at night, long after the day visitors have left. The architecture is pure Ando: sweeping concrete curves, dramatic atriums, and windows framing the sea and landscape like living paintings. Then there’s “Oval,” the most exclusive and architecturally striking part of the hotel. Situated atop a hill and accessible only by a private monorail, it consists of just six rooms arranged around a large, open-air oval pool that mirrors the sky. Being there feels like entering a secret realm of reality. The journey itself—the quiet monorail ride through the forest—is part of the ritual, a cleansing of the senses before arriving at this minimalist sanctuary. The entire design of Benesse House is about orchestrating your experience, directing your gaze, and shaping your movement to foster a deeper connection with both art and environment.

Chichu Art Museum: The Underground Temple of Light

Although overnight stays aren’t possible, any conversation about Naoshima or Ando’s philosophy is incomplete without mentioning the Chichu Art Museum. “Chichu” means “in the earth,” and the museum is built almost entirely underground to preserve the natural beauty of the island’s coastline. This is Ando’s masterpiece. From above, all you see are geometric incisions in the green hillside. Inside, it is an underground realm of concrete chambers created to showcase just three artists: Claude Monet, Walter De Maria, and James Turrell. The sole source of light is natural sunlight. The entire museum functions as a device for capturing and manipulating daylight. Monet’s “Water Lilies” series is seen not under glaring gallery spotlights but in a vast, white-walled room illuminated by soft, diffuse light from a hidden skylight above. The light shifts with the weather and time of day, ensuring you never view the paintings the same way twice. James Turrell’s light installations provide spiritual experiences, playing with your perception of space and reality inside rooms carefully designed by Ando as perfect, silent vessels. The Chichu is more than a museum; it’s a pilgrimage site, embodying the ultimate expression of this architectural philosophy: using the heaviest, most unyielding material to celebrate the most ethereal and fleeting element—light itself.

Urban Sanctuaries and Forest Retreats: The Style Evolves

The Ando-inspired concrete aesthetic is no longer limited to isolated art islands. It has been embraced, transformed, and reinterpreted by a new wave of architects and hoteliers throughout Japan, crafting distinctive retreats in both vibrant urban centers and tranquil forests. These contemporary examples highlight the versatility and adaptability of the style, proving it is not a rigid formula but a dynamic, evolving design language.

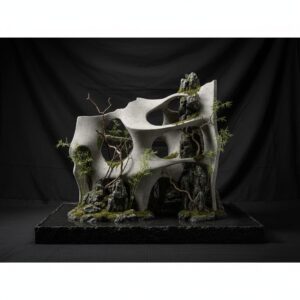

Hotel Keyforest Hokuto: Jomon Futurism

Nestled deep in Yamanashi’s forests near Kobuchizawa Art Village, Hotel Keyforest Hokuto, designed by Atsushi Kitagawara, marks a bold departure from Ando’s serene minimalist geometry. Its jagged, sharp concrete forms feel almost chaotic, resembling massive, futuristic rock fragments breaking through the forest floor. This design evokes what could be described as “Jomon-era futurism,” inspired by Japan’s prehistoric era known for its energetic pottery. Inside, the space is a maze of sharp angles and unexpected rooms that resemble high-design caves. The hotel showcases a more expressive and forceful use of concrete, not seeking quiet harmony with nature in the Ando tradition, but instead forging a dramatic, even confrontational conversation with it. It asserts that modern architecture can be as wild and untamed as the wilderness it inhabits, demonstrating that the concrete aesthetic can be bold, playful, and remarkably unconventional.

TRUNK(HOTEL) YOYOGI PARK: Concrete Goes Social

In the center of Tokyo, the recently opened TRUNK(HOTEL) YOYOGI PARK reveals how this style has been tailored for a young, trendy urban audience. While maintaining abundant sleek concrete and minimalist elements, the space is far from a quiet retreat. It functions as a social hub. Here, concrete is combined with warmer materials such as wood and abundant greenery, emphasizing communal areas: a lively rooftop bar and infinity pool overlooking one of Tokyo’s largest parks, a bustling lobby lounge, and a restaurant that extends into the neighborhood. The aesthetic serves a distinct purpose, signaling a connection to refined design, authenticity, and industrial-chic coolness. It’s less about Zen tranquility and more about crafting a stylish, exclusive urban clubhouse for the creative community. This proves that the concrete ethos can be fused with a sociable, extroverted energy, making it appealing to a new generation who desire both flawless design and a sense of belonging.

Bessou UMI to MORI: A Dialogue of Materials

Situated in the seaside resort town of Atami, Bessou UMI to MORI (Villa Sea and Forest) presents a compelling study in contrasts. The hotel blends old and new. Its main building, designed by the architectural powerhouse Takenaka Corporation, is a sleek concrete-and-glass modernist block perched on a hillside, with all rooms oriented to frame expansive, unobstructed ocean views. The focus here is on capturing the vastness of water and sky. Adjacent is the bathhouse by Kengo Kuma, renowned for his expertise with wood and often regarded as a philosophical counterpart to Tadao Ando. Kuma’s design features warm, aromatic cedar and intricate wooden joinery. Staying here allows guests to experience two dominant strands of modern Japanese architecture in one location: retreating to the cool, minimalist concrete sanctuary and then moving to bathe in a warm, organic wooden haven. It perfectly encapsulates the ongoing dialogue in Japanese design between industrial and natural elements, modernity and tradition, showing that these styles can harmoniously coexist to create a richer, more layered experience.

The Reality Check: Is This Vibe Actually For You?

Alright, let’s get to the point. We’ve discussed philosophy and aesthetics, but is staying in a concrete box actually… enjoyable? Here’s where managing expectations is crucial, because this particular style of luxury definitely isn’t for everyone. It’s a distinct taste, and you should consider whether it’s one you’ll truly appreciate before spending a significant amount on it.

The Comfort Question

First, the comfort aspect. A room constructed from concrete, glass, and steel can, unsurprisingly, feel cold—not only in appearance but also physically. These materials don’t retain heat like wood or fabric do. Acoustically, the space can be harsh as well; sound often echoes in such minimalist environments. The furniture usually matches the architecture’s minimalism—a low-profile bed, a single designer chair that looks better than it feels. If your idea of luxury in a hotel involves plush, overstuffed armchairs, thick carpets, and layers of soft textiles, you might find these rooms stark and uninviting. The luxury here isn’t about indulgent comfort; it’s about sensory discipline. It’s about appreciating the beauty of the space itself, rather than the cozy amenities within it. You must be willing to exchange some conventional coziness for the experience of inhabiting a piece of architectural art.

The Price Tag and The ‘Gram

These hotels tend to be pricey. You’re not simply paying for a bed; you’re paying for the architectural lineage, the designer’s brand, exclusivity, and the artistic value. The appeal lies in the experience. So ask yourself: Are you an architecture lover who will spend hours admiring how light interacts with a wall, or are you primarily seeking a comfortable base to explore from? There’s no right or wrong answer, but being honest with yourself is vital. There’s also the risk of falling into an “Emperor’s New Clothes” effect. Because these places are so hyped and visually arresting, it’s easy to feel pressured to find them profound. But it’s perfectly fine if you find them empty instead. It’s worth examining your own reasons. Are you drawn to minimalism and quiet reflection, or are you motivated by how impressive your Instagram photos will look? No judgment either way, but the experience will be far more fulfilling if it aligns with your true personality.

A Vibe Check: Who It’s For vs. Who It’s Not

Here’s a breakdown. This experience is probably for you if:

- You’re a sincere admirer of architecture, art, and design, seeing buildings as destinations in themselves.

- You’re an introvert or crave a genuine escape from the noise and chaos of daily life.

- You appreciate the beauty of minimalism, clean lines, and stark simplicity.

- You desire a unique, memorable, thought-provoking travel experience, and are willing to trade some traditional comforts for it.

This experience is probably not for you if:

- You’re traveling with young children—those sharp concrete corners are a parent’s nightmare.

- You define luxury by warmth, coziness, and attentive, pampering service.

- You want a hotel with a vibrant, social atmosphere and plenty of amenities.

- You’re on a budget. The price-to-comfort ratio, by conventional standards, can be difficult to justify.

The Bigger Picture: Concrete as Modern Japanese Identity

So, what does all this signify? Why has this stark, concrete aesthetic taken such a strong hold in Japan? Looking at the bigger picture, it can be seen as a powerful and necessary response to the realities of modern Japanese life. Most people live in cities that are visually dense, cluttered, and often cramped. Signage, overhead wires, and buildings merge into a chaotic visual symphony. The appeal of these minimalist concrete structures lies in their offering a radical moment of visual silence. They serve as an architectural palate cleanser, a deliberate and potent creation of negative space in a culture where it is scarce.

This is not a passing trend. It is the continuation of a distinct strand of Japanese modernism that has been developing for nearly a century. It taps into a deep and lasting cultural yearning for simplicity, a connection to nature (though highly curated), and spaces that foster reflection. It is the Zen rock garden reinterpreted for the 21st century. The rocks and raked sand have been replaced by concrete and light, but the core purpose—to create a stylized microcosm of nature that soothes the mind—remains unchanged.

Ultimately, this architectural style is a quiet yet extraordinarily confident expression of modern Japanese identity. In a globalized world where luxury hotels from New York to Dubai can seem interchangeable, these buildings are unapologetically and uniquely Japanese. They do not conform to a generic international standard of luxury. Instead, they embody a distinctive philosophy of what luxury can be: space, silence, and a profound connection to a specific moment in time and place. It is a subtle power play. These concrete fortresses are more than hotels; they are inhabitable sculptures, philosophical statements you can stay within. They do not offer simple answers or easy comforts. They challenge your expectations of what a hotel should be, and in doing so, they challenge your perceptions of Japan itself. And that, ultimately, is the real essence. It is the experience of being invited to ponder the question, rather than simply being handed the answer.