Alright, let’s have a real chat. You’ve done Japan. You’ve had the ramen that changed your life, got beautifully lost in Shinjuku Station, and felt that deep, historical hush in a Kyoto temple. You’ve seen the photos, you’ve bought the souvenirs, you get the general vibe. You’re ready for the next level, the director’s cut of Japan. And then someone, a friend who’s really into design or maybe a travel blog, drops a name: Tadao Ando. They tell you, with a very serious look in their eyes, that you have to go to this church, or this museum on a remote island. You’re intrigued. You pull up Google Images and… wait. Is that it? It’s… concrete. Like, a whole lot of grey, smooth, no-frills concrete. It looks like a super stylish bunker or maybe the world’s most aesthetic skatepark. And you’re thinking, “Hold up. I came to Japan for ancient wooden temples with swooping roofs and gardens raked into perfection. You’re telling me the spiritual glow-up I’m looking for is inside… a concrete box?” No cap, the confusion is legit. It feels like a total mismatch. How can a material we associate with underpasses and industrial estates possibly be a sanctuary for the soul? This isn’t the Japan from the postcards. But here’s the secret, the thing you only get when you’re standing inside one of these spaces, feeling the sun move across the wall: it’s not just concrete. It’s a feeling. It’s an entire philosophy made solid. It’s one of the most profound and genuinely Japanese experiences you can have, and it’s hiding in plain sight. So, if you’re ready to have your expectations flipped and find a stillness you didn’t know you were looking for, let’s dive into the world of Tadao Ando. It’s a trip, and absolutely worth the journey.

To further explore how concrete shapes Japan’s modern identity, consider the profound impact of its brutalist civic halls.

The Concrete Curveball: “Wait, This Is a Temple?”

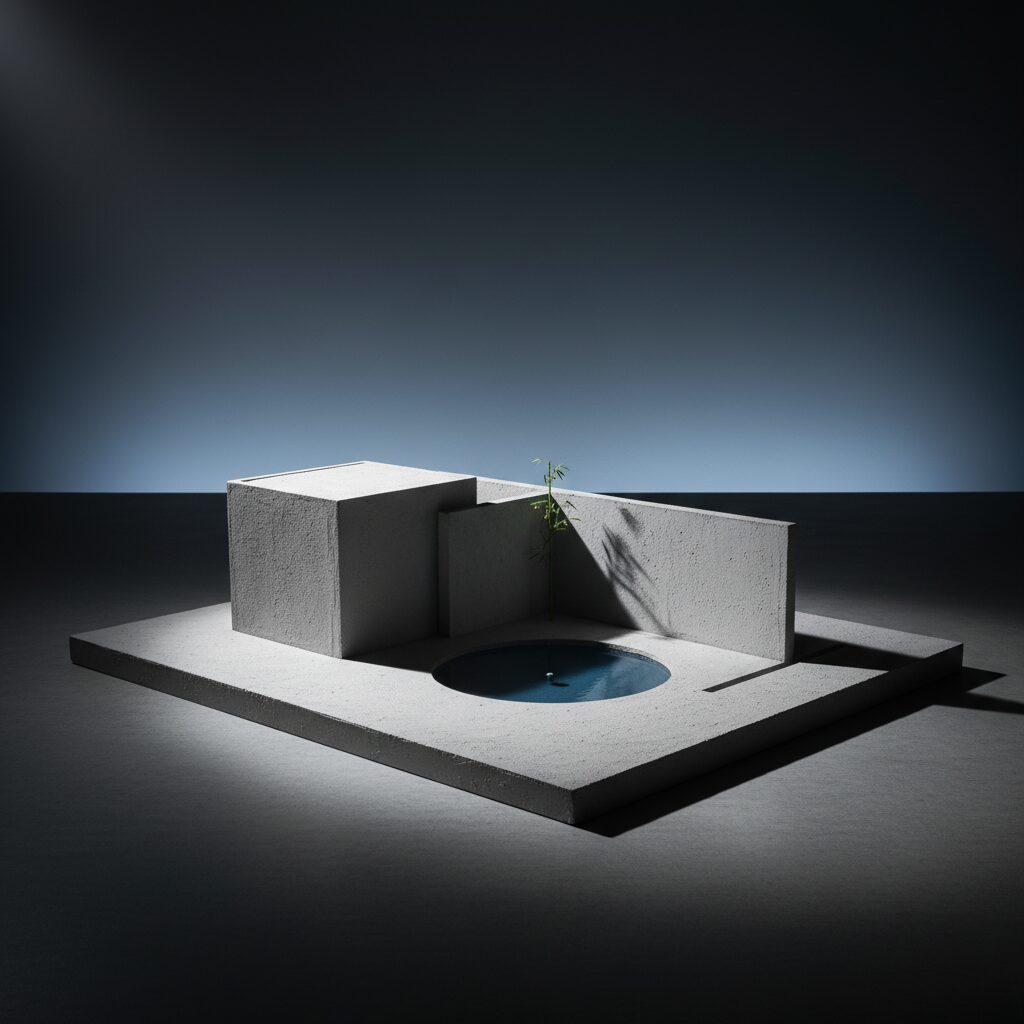

Let’s be brutally honest for a moment. The first time you stand before a major Ando building, especially if you’ve just come from, say, the dazzling gold leaf of Kinkaku-ji or the vibrant chaos of Senso-ji, the experience can be disorienting. It’s a complete shift in atmosphere. Your mind, trained to link “Japanese sacred space” with dark wood, intricate joinery, paper screens, and the scent of aged tatami and incense, encounters a strong contradiction. Before you stands a monument of concrete. Not just any concrete, mind you — we’re talking vast, seamless walls of the smoothest, most perfectly poured grey you’ve ever seen. It’s flawless, uniform, and immense. There are no carvings, no paint, no embellishments. Just the raw, unadorned material itself, formed into bold, clean geometric shapes—circles, squares, and long, curving walls that guide your gaze and your movement.

For many from Western backgrounds, concrete carries heavy associations. It’s the material of city parking lots, stark Cold War-era monuments, and unfinished basements. Functional, yes, but rarely viewed as beautiful, let alone spiritual. It feels cold. Impersonal. Heavy. It’s the substance of urban sprawl, not quiet reflection. You might trace your hand along the wall, expecting it to be rough and gritty, yet it’s often surprisingly smooth, cool to the touch like stone. The air inside these spaces holds a different quality—still, quiet, with sounds that echo in a distinctive, almost monastic way. But the initial impression is one of stark, minimalist, and perhaps even intimidating austerity. There you stand, looking at a building that seems to reject every single stereotype of traditional Japanese design, and you have to wonder: What am I missing? Why does this place, resembling a fortress of solitude, attract pilgrims from across the world? The answer isn’t visible on the surface. It lies in the space the concrete forms, the light it captures, and the way it compels you—if only for a moment—to be fully present.

Ando 101: It’s Not Just Concrete, It’s a Whole Mood

To truly understand Ando, you need to rewire your brain a bit. You must stop viewing concrete as the main attraction. In his vision, concrete serves as the frame, not the artwork. The materials he’s genuinely passionate about are invisible: light, shadow, wind, water, and space itself. Think of his buildings less as objects and more as instruments designed to play nature’s music. He famously said, “I don’t believe architecture has to speak too much. It should remain silent and let nature in the guise of sunlight and wind speak.” That, right there, is the key that unlocks everything.

He uses concrete to craft simple, powerful forms that capture and shape sunlight. A long, narrow skylight isn’t merely a window; it’s a stroke of light painting a line across a dark wall, a line that moves and shifts throughout the day. A massive wall with a single, square opening doesn’t just offer a view; it frames a section of the sky, transforming it into a living, dynamic artwork. The stark gray walls make the green of a single tree or the deep blue of the framed sky appear infinitely more vibrant. The concrete offers silence so you can hear nature’s whisper.

Here, we also encounter a central Japanese aesthetic concept: ma (間). This famously difficult word to translate roughly means negative space, an interval, a gap, or the space between things. Western thought often focuses on the objects themselves, but in Japanese aesthetics, the space around objects is just as crucial, if not more so. It’s the silence between notes that creates music. It’s the unpainted section of a scroll that allows the image to breathe. Ando is a master of ma. His vast, empty concrete walls evoke a profound sense of space. Their simplicity is intended to clear your mind. By removing all typical distractions—the decorations, patterns, clutter—he directs your attention to your own experience. You begin to notice the subtle shift in light as a cloud passes overhead. You hear the echo of your footsteps. You feel the cool air on your skin. His architecture doesn’t tell you what to think or feel; it creates a perfectly tuned space for you to simply be. The concrete isn’t cold and barren; it’s calm and full of possibility. It’s a minimalist stage for the maximum drama of the natural world and your inner landscape.

The Glow-Up from Wabi-Sabi to Brutalism

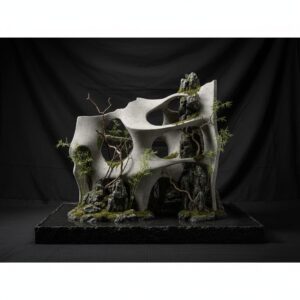

So how does this stark, modern minimalism relate to older Japanese traditions? It might seem like a huge jump from a rustic, moss-covered teahouse to a pristine concrete cube. Yet the philosophical essence is surprisingly similar. The connection lies in another key Japanese aesthetic concept: wabi-sabi (侘寂). Though difficult to translate precisely, it represents a worldview centered on embracing transience and finding beauty in imperfection. It’s about appreciating profound beauty in things that are humble, modest, natural, and unconventional—the charm of a slightly misshapen handmade tea bowl, the patina on an old metal gate, or the fleeting bloom of cherry blossoms.

So where is the wabi-sabi in Ando’s flawless-looking concrete? Look closely. He is famously meticulous about his concrete, using high-density, waterproof mixes and custom wooden forms (cedar or cypress) to achieve that signature smooth surface. The placement of the tie-rod holes—those small circular marks on his walls—is arranged with the precision of a Zen archer. Yet it remains a natural material. Up close, you notice subtle color variations, faint traces of the wood grain from the forms, and tiny air bubbles creating a unique texture. Over time, these walls live and breathe. Rain stains create dark patterns that map the building’s history against the weather. In damp corners, a thin veil of green moss may begin to grow. Ando embraces this. He isn’t crafting sterile, unchanging boxes; instead, he uses a raw, almost elemental material and allows it to come to life.

This is the unexpected transformation. He took the spirit of wabi-sabi—the appreciation of raw materials, simplicity, and the passage of time—and expressed it through the language of 20th-century modernism. From afar, his work might be grouped with Brutalism, a Western architectural style known for blocky, imposing concrete buildings. But the experience feels entirely different. Brutalism often conveys heaviness, aggression, and oppression, symbolizing state power. Despite using the same fundamental material, Ando’s work feels light, contemplative, and intimately connected to its surroundings. He doesn’t impose the building on the landscape; he uses the building to reveal the landscape anew. He discovered the soul, the wabi-sabi, hidden within an industrial material and transformed it into poetry.

The Pilgrimage: Your Deep Dive into the Concrete Sanctuaries

Once you grasp the philosophy, you need to experience it firsthand. An Ando building cannot be fully appreciated through photos alone. It requires your physical presence. It’s a full-body, sensory encounter. Visiting one of his masterpieces is not merely sightseeing; it’s more like a secular pilgrimage, a journey to a place designed to shift your perspective.

Naoshima: The Art Island Experience

Naoshima is the undisputed mecca for Ando enthusiasts. This small island in the Seto Inland Sea was once a quiet fishing village suffering from industrial decline. Then, in the late 1980s, the Benesse Corporation decided to transform it into a world-class center for contemporary art and architecture, with Tadao Ando as the lead architect. The result is a place unlike any other on earth, where art is not confined to a museum; it is the museum, the landscape, and the entire experience of being there. The journey itself becomes part of the process. Taking the ferry from the mainland, you feel life’s pace slow down. You leave behind the urban rush and enter a different kind of reality.

Your first major destination will likely be the Chichu Art Museum, which, honestly, might spoil all other museums for you. “Chichu” means “in the earth,” and the entire museum is constructed underground to preserve the natural beauty of the island’s coastline. From outside, it’s barely visible—just some geometric openings cut into a green hill. You purchase your ticket for a specific time slot, a system designed to ensure the spaces never feel crowded. Inside, it’s a masterpiece of architectural choreography. You move through a series of concrete courtyards, ramps, and corridors. The spaces alternate between cool, shadowy passages and open-air courtyards that frame the sky. The walk itself refreshes your mind.

Then you reach the art. Only three artists are on permanent display, and Ando designed a unique sanctuary for each. To view Claude Monet’s “Water Lilies” series, you must first take off your shoes and wear soft slippers. You enter a vast, white room with rounded corners, floored in tiny cubes of cool Carrara marble. The only light is natural, diffused from a ceiling you cannot quite see, giving the light a celestial, ethereal quality. It shifts with the weather outside. On sunny days, the paintings glow; on cloudy days, they feel moody and contemplative. Ando has created the perfect environment for these paintings, a space that lets them breathe unlike any traditional gallery. The experience with Walter De Maria’s installation—a single giant granite sphere and gold-leafed wooden sculptures in a massive concrete hall reminiscent of a modern cathedral—and James Turrell’s light installations, which manipulate your perception of space and reality, are equally profound. At Chichu, you don’t just look at art; you inhabit it.

Elsewhere on the island, there’s Benesse House, a structure that brilliantly fuses a museum with a luxury hotel. You can literally sleep inside the museum. Imagine waking up, stepping out of your room, and immediately facing works by Andy Warhol or Jasper Johns, all while gazing through a vast concrete-framed window at the sparkling sea. The boundaries blur completely. Finally, there’s the Ando Museum, a small treasure in the traditional village of Honmura. Here, Ando inserted a stark concrete cube inside a 100-year-old wooden house, creating a striking dialogue between old and new, light and shadow, wood and concrete. It’s a perfect, bite-sized summary of his entire philosophy. Naoshima is not a one-day outing. It’s a place to slow down, to walk, to look, and to feel the extraordinary synergy among nature, art, and Ando’s concrete poetry.

Church of the Light, Osaka: Where God is a Sunbeam

If Naoshima is Ando’s epic poem, the Church of the Light is his perfect haiku. Located in a quiet residential suburb of Ibaraki, a city near Osaka, this small Christian chapel is one of the most powerful and renowned spiritual spaces of the 20th century. From the street, it appears deceptively simple, almost forgettable. It’s a concrete box standing beside an existing wooden church. There’s no steeple, no grand entrance, no stained glass. You could easily walk right past it.

But upon entering, the world shifts. You are enveloped in deep, cool, profound darkness. The space is small and intimate. The walls are that signature, impossibly smooth concrete. The floor and simple pews are made of dark-stained wood—actually scaffolding planks—adding a touch of rustic warmth and humility. Your eyes take a moment to adjust. Then you see it. Behind the altar, the entire east-facing wall is solid concrete except for two intersecting slits—one vertical, one horizontal—cut clean through the 15-inch-thick wall. Through these slits, raw, unfiltered daylight streams in, forming a brilliant, radiant cross of pure light.

That’s the entire design. There are no icons, statues, or paintings. The cross is not a crafted object of gold or wood placed in the church; it is the absence of material, a void filled by the most fundamental force in the universe: light. The effect is breathtaking and deeply moving. It’s a spiritual experience distilled to its essence. The cross is never static; it constantly changes. In soft morning light, it’s a gentle, hazy glow. At noon on sunny days, it becomes a razor-sharp blade of blinding brilliance. On gray, rainy days, it shimmers softly in silver. The church is alive, in constant dialogue with the sun, clouds, and seasons. By stripping everything else away, Ando compels you to confront the power of this single, simple, profound idea. It proves you don’t need gold or marble to touch the divine. Sometimes, a dark room and a glimpse of light are all it takes.

The Hill of the Buddha, Sapporo: The Ultimate Reveal

On the northern island of Hokkaido, within the vast Makomanai Takino Cemetery on the outskirts of Sapporo, lies one of Ando’s most dramatic and ingenious projects. For years, a 13.5-meter-tall stone Buddha statue stood alone in a field, imposing but somewhat ordinary. The cemetery’s owners wanted to create a more serene, reverent setting, so they invited Ando. His solution was bold. Instead of constructing a temple around the Buddha, he chose to conceal it. He built a massive, man-made hill planted with 150,000 lavender plants and buried the statue so that only the very top of its head was visible from afar, peeking out as if meditating among the flowers.

To see the Buddha, you embark on a carefully choreographed journey. The experience itself is everything. First, you approach through a tranquil water garden, reflecting the sky and cleansing the mind. You walk along its edge, catching glimpses of the Buddha’s head above the hill. Anticipation builds. Then you enter the hill through a long, 40-meter concrete tunnel. The interior is dark, cool, and womb-like. The curving concrete walls are subtly folded, creating a play of light and shadow guiding your way. There is a sense of compression, moving from the open world into a sacred, enclosed space.

Finally, you emerge from the tunnel into a vast, circular, open-air hall at the hill’s core. There, you look up. The great Buddha statue sits in sublime stillness, its full form revealed and framed against a perfect circle of sky. The effect delivers a powerful emotional impact. The light haloing from above illuminates the stone, lending it a divine glow. You’ve been on a pilgrimage. Cleansed by water, compressed by earth, then reborn into the light at the Buddha’s feet. Ando hasn’t merely built a structure; he has crafted a narrative. He uses architecture to control the reveal, build suspense, and fundamentally transform your perception of the statue. You don’t just see the Buddha; you arrive at it. In summer, the hill blooms with purple lavender; in winter, it becomes a pristine dome of white snow. It stands as a testament to how architecture can inspire reverence and turn simple viewing into a profound spiritual event.

Awaji Yumebutai: A Concrete Garden of Hope

If you want to witness Ando’s principles applied on a grand, sprawling scale, visit Awaji Yumebutai. This vast complex on Awaji Island serves as a conference center, hotel, and memorial park, but that description barely touches its soul. The project bears a deeply poignant backstory. The site was initially a mountainside stripped and excavated to supply landfill for Kansai International Airport in Osaka Bay. Ando’s original plan was to create a park to restore the damaged natural environment. However, after the 1995 Great Hanshin Earthquake devastated the region—claiming over 6,000 lives with its epicenter just off Awaji Island—the project’s focus shifted. It no longer centered only on ecological restoration; it became a memorial to the victims and a symbol of rebirth and hope.

Yumebutai, meaning “stage of dreams,” is a labyrinth of concrete plazas, water features, greenhouses, and gardens. It represents Ando’s architectural language expanded into a full vocabulary. The most striking feature is the Hyakudanen, or “hundred-stepped garden.” It’s a grid of 100 square flowerbeds cascading down the hillside—a permanent floral calendar and a powerful tribute to those who lost their lives. Walking up the grand staircases flanking this garden is almost overwhelming. Elsewhere, you’ll find vast, shallow reflective pools, concrete walls adorned with millions of scallop shells (a local byproduct that enhances water absorption and texture), and tranquil plazas inviting quiet contemplation. Water flows constantly through channels and fountains, its sound a soothing contrast to the silent concrete. Despite its complexity, the space never feels chaotic. Ando’s signature geometric order provides a calming framework for the wildness of flowers, the movement of water, and nature’s resilience. It acknowledges deep tragedy while celebrating life, memory, and the power of renewal. It is not a sad place; it is profoundly hopeful.

The Vibe Check: How to Actually Feel the Zen

So, you’ve made the journey and now find yourself inside one of these concrete marvels. What next? It’s easy to slip into tourist mode: snap a photo of the light cross, take a selfie with the Buddha, and move on. But to truly understand it, you need to change your approach. This isn’t a checklist; it’s an invitation to enter a different state of mind. It’s a vibe check, and the vibe is slow, quiet, and present.

First, put your phone away. Seriously. Instagram can wait. These spaces were created long before smartphones existed, and they require a focus that a screen disrupts. Your initial task is simply to exist in the space. Find a bench, or a quiet corner, and sit down. For at least ten minutes. Don’t do anything. Just be.

Next, engage all your senses. What do you see? Don’t just look at the building; observe the light. Notice how it falls on a wall, how its shape shifts as time passes. Take note of the textures. Run your hand along the concrete. Is it smooth? Does it have a grain? Is it warmed by the sun or cooled by the shade? What do you hear? In the city, we’re used to tuning out noise. Here, listen to the silence. Hear your own breathing. Notice the echo of a distant footstep, the whisper of the wind weaving through an opening, the soft sound of water. These are the sounds Ando wants you to perceive. What do you feel? The temperature change as you move from an open courtyard into an enclosed corridor. The breeze touching your skin. The sense of scale, of being a tiny human in a vast, quiet place.

Walk slowly. These buildings are crafted as a series of experiences. The journey through them matters as much as any single viewpoint. Pay attention to the transitions—from light to dark, from tight spaces to expansive ones. Ando is guiding you, orchestrating your experience. Let him. By slowing down and tuning in, you move from being a passive observer to an active participant. You’re not merely looking at a building; you’re having a conversation with it. That’s where the Zen lies. It’s not in the concrete itself; it’s in the quiet, focused mindset that the concrete helps you discover.

So, Is It Worth It? The Real Tea for Return Visitors

Let’s get straight to the point. For a returning visitor who has already checked off the Golden Route highlights, is it truly worth spending valuable holiday time and a significant amount of yen to visit a collection of concrete buildings, some situated in quite remote areas? The answer is an emphatic, unequivocal yes—if you want to gain a deeper understanding of Japan. While your first trip focused on experiencing the country’s beautiful, historical surface, a pilgrimage to Ando’s works is about delving into its modern soul.

These buildings are more than architecture; they embody a living philosophy. They represent the 21st-century evolution of the Zen rock garden, the contemporary counterpart of the humble teahouse. They address fundamental themes central to Japanese aesthetics: the harmony between humanity and nature, the elegance of simplicity, the spiritual significance of emptiness, and the passage of time. Visiting an Ando site is like unlocking a new room in the museum of Japanese culture. It reveals how ancient concepts are being reinterpreted and sustained in a hyper-modern world.

This experience goes beyond just seeing another temple or museum. It’s about encountering an idea, a feeling, a mood. It’s about realizing that in Japan, a simple concrete wall, when touched by light in just the right way, can feel more sacred and moving than the most elaborate cathedral. This journey is for the traveler who no longer asks “What should I see?” but begins to wonder “Why is it like this?” The answer won’t be found in a guidebook. Yet it may await you in the silence of a concrete sanctuary, at the perfect intersection of light.