Yo, what’s the deal with Japan? You scroll through the ‘gram, you see these minimalist cafés, the crazy-perfect bento boxes, the knives that look like they could slice through time itself. You might’ve even copped a souvenir or two on a trip—a pen that writes like a dream, a ceramic bowl that just feels right in your hands. And there’s this… vibe. This intense, next-level attention to detail that feels almost spiritual. It’s in everything, from a high-speed train to a simple pair of scissors. The question that’s probably bouncing around in your head is, “Is this for real, or is it just some genius-level marketing?” Why does a simple object made in Japan often feel like it has more soul than my last situationship?

This isn’t just about ‘quality control’ or being ‘well-made’. That’s the surface-level take. The real answer is way deeper, a whole cultural operating system called Mono-zukuri (ものづくり). Break it down, and it literally means ‘thing-making’. But translating it like that is like calling a Beyoncé concert just ‘singing’. It misses the whole point. Mono-zukuri is the art, the science, the philosophy, and the relentless, borderline-obsessive spirit of creation that’s baked into the Japanese psyche. It’s a mindset that says the process of making something is just as important, if not more so, than the finished product itself. It’s the ‘why’ behind the silent, seamless service, the impossibly punctual trains, and the kitchen knife that costs more than your rent. We’re about to peel back the layers on this thing, go beyond the hype, and get to the core of why Japan is like this. Forget the glossy travel brochures; this is the real, unfiltered story. And to get a sense of where this philosophy isn’t just an idea but a whole town’s reason for being, check out the map below. This is Tsubame-Sanjo, a place where Mono-zukuri is the literal air they breathe.

This philosophy of meticulous creation even extends to the art of Kyaraben, where everyday bento boxes are transformed into intricate character art.

The Vibe Check: What Mono-zukuri Isn’t

Before we can truly understand what Mono-zukuri is, we first need to clarify what it definitely is not. The internet and pop culture have presented a somewhat distorted view of Japanese craftsmanship, often focusing on a handful of clichés that overlook the rich, complex, and deeply human reality behind it. It’s easy to assume you get it by admiring a perfectly lacquered box or a flawlessly functioning camera, but that’s merely the highlight reel. The real story is far more textured, nuanced, and, honestly, much more fascinating.

It’s Not Just About ‘Perfection’

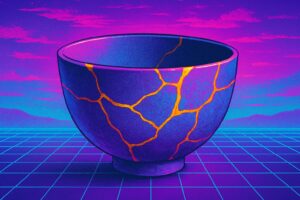

The biggest misconception we need to debunk is the notion of sterile, robotic perfection. From the outside, Japanese quality might appear as if it were produced by machines in a spotless environment, entirely devoid of human influence. It’s an image of impeccable symmetry and products without a single flaw. But that’s a complete misunderstanding. Genuine Mono-zukuri doesn’t just tolerate imperfections; it embraces them. It recognizes that the craftsman’s touch, the subtle variation in a bowl’s glaze, the barely noticeable weight difference in a hand-forged tool—that’s where the object’s essence lies. This is connected to the aesthetic concept of wabi-sabi (侘寂), which values beauty in imperfection, transience, and incompletion. A hand-thrown teacup isn’t prized for being a perfect circle, but because you can feel the potter’s thumbs pressing into the clay. Its surface tells the story of its creation. Consider kintsugi (金継ぎ), the art of repairing broken pottery with gold lacquer. Rather than hiding cracks, it celebrates them, highlighting the object’s history and resilience. The flaw becomes its most striking feature. So, no, it’s not about being flawless. It’s about authenticity—a process that’s honest and true to both the materials and the maker. It’s a perfection of intention and effort, not a sterile perfection of the result.

It’s Not Just ‘Ancient Tradition’

Another misconception is that this is all about preserving dusty old traditions from the samurai era. Mention “Japanese craftsman,” and you might picture a wise elder sitting cross-legged in a wooden workshop, hand-planing wood for a temple. While such figures certainly exist and are admirable, they represent only a small part of a much larger story. Mono-zukuri is a living, evolving practice. It’s not about replicating the past but about carrying the spirit of tradition into the future. It’s a dynamic blend of old and new. You’ll find sword-polishing masters, using techniques passed down for centuries, now crafting mirror-like finishes on modern iPhones. You’ll see textile artisans from Kyoto, whose families have woven silk for generations, applying their extensive knowledge to develop advanced carbon fiber composites for aerospace and Formula 1. This isn’t a choice between tradition and technology; it’s using tradition as technology. The deep, intuitive understanding of materials and processes, refined over hundreds of years, is applied to cutting-edge challenges. This is why a Japanese company might spend years perfecting a new ballpoint pen ink—it may seem trivial, but it stems from the same commitment as the swordsmith who devoted his life to honing a blade. The dedication remains the same; only the final product differs. Mono-zukuri isn’t a dusty relic; it’s a springboard to innovation.

It’s Not a Top-Down Corporate Mandate

You might suspect that this philosophy is a calculated corporate branding tactic devised by executives at Toyota or Panasonic to boost sales of cars and gadgets. While major companies have certainly adopted and systematized elements of it—such as Kaizen—the roots of Mono-zukuri run deep in grassroots culture. It’s a bottom-up tradition, not a top-down command. The true driving force behind Mono-zukuri is the shokunin (職人), a term meaning artisan or craftsperson but carrying the profound weight of a lifelong vocation. This spirit isn’t confined to renowned artists; it’s embodied by the man running a small workshop manufacturing a highly specialized screw for industrial machines, or the woman who has spent her entire life perfecting the art of soy sauce brewing. These individuals earn great respect in Japanese society—not for wealth or rank, but for their mastery and dedication. This pride and sense of responsibility permeate every link in the supply chain. The person crafting that tiny, seemingly insignificant screw understands that the integrity of their work affects the final product, whether a bullet train or a medical device. They aren’t just making parts; they are upholding a standard—a deeply personal commitment echoed across thousands of small, interconnected businesses, forming a resilient network of quality. It’s not just a marketing slogan; it’s a shared social contract.

The Deep Dive: Unpacking the Core Elements

Alright, we’ve clarified what Mono-zukuri is not. Now, let’s dive into its core. What are the essential elements that form this secret recipe? It’s not a simple checklist but a combination of interconnected concepts and attitudes that together create this distinctive approach to craftsmanship. It involves a mix of spiritual dedication, meticulous attention to detail, and a continual cycle of improvement. Grasping these fundamental pillars is key to experiencing that “Ah, now I understand” moment.

The Shokunin Spirit: A Lifelong Commitment

At the center of it all is the shokunin (職人). This is more than a job title; it’s an identity and a way of life. A shokunin is someone who devotes their entire being to mastering a single craft. It’s a pursuit of excellence for its own sake. The famed sushi chef Jiro Ono once remarked, “You must fall in love with your work.” This captures the emotional core of the shokunin spirit. It’s not about punching a clock; it’s a spiritual and intellectual commitment to the craft, tools, materials, and customers. The journey to mastery is long and challenging. The traditional apprenticeship system is rigorous. An aspiring chef might spend years simply washing rice. A novice carpenter could spend a decade sharpening tools and keeping the workshop clean. To outsiders, this might seem like harsh and inefficient hazing, but it is not. It’s a process designed to dissolve ego and cultivate foundational virtues: patience, humility, and acute observation. Before you can create, you must learn to truly see and respect the process. You absorb the rhythm of the work until it becomes instinctual, deeper than conscious thought. This is why a shokunin’s movements are often fluid and efficient, with no wasted energy. Every action has been refined through tens of thousands of hours of practice. This lifetime of focused dedication enables a level of skill that borders on the extraordinary. It’s a commitment that transcends mere employment and becomes a profound journey of self-cultivation.

Kodawari: The ‘Obsessive’ Quest for Perfection

If the shokunin is the individual, then kodawari (こだわり) is their unique strength. This Japanese word is notoriously difficult to translate because it encapsulates a full mindset. It blends “uncompromising,” “meticulous,” “fastidious,” and “obsessive attention to detail.” It expresses a passionate refusal to settle for “good enough.” Kodawari is the invisible force driving quality beyond logical or economic reasoning. It’s the ramen chef who travels across prefectures to find the perfect salt for his broth, a subtlety most customers wouldn’t even notice. It’s the denim artisan who insists on using an ancient shuttle loom for its distinct, uneven texture, despite being far less efficient than modern machines. It’s the automotive engineer who dedicates months fine-tuning the sound of a closing car door—not for safety, not for function, but to create a solid, reassuring feel. Kodawari is sweating the smallest details—the micro nuances absent from specs but essential to superb quality. It’s a personal, often implicit standard of excellence. It’s the internal voice insisting, “I can do better.” This is why interacting with a finely crafted Japanese product is so gratifying. You sense the countless hours of deliberation, refinement, and passion invested in every curve, texture, and sound.

The Material as Your Senpai

A vital aspect of this philosophy is the relationship with raw materials. In Western perspectives, materials often appear as inert resources to be conquered and shaped by human will. In the Mono-zukuri mindset, it’s an entirely different relationship. Rooted in Japan’s indigenous Shinto beliefs, where gods and spirits (kami) inhabit natural objects, there is profound respect for the materials themselves. The material is not something to dominate; it is a partner in creation. It is your senpai—your senior and mentor. A carpenter does not merely cut wood; they study its grain, sense its tension, understand its history, and listen to what it wants to become. Their role is to reveal the wood’s inherent beauty and strength, not to impose their design on it. A blacksmith develops an intuitive understanding of steel by reading the colors of heated metal to gauge its exact condition. A potter is aware that clay retains memory, and how it is handled influences the final firing. This “dialogue with the material” is fundamental. It explains the intense focus on sourcing the finest components—whether premium steel for a knife, pure water for sake, or lustrous silk for a kimono. The finished piece is a collaboration between the shokunin’s skill and the spirit of the material. You don’t merely use it; you honor it.

Kaizen: The Continuous Pursuit of Betterment

If kodawari is the fervent passion, kaizen (改善) is the methodical, unceasing drive to improve. Meaning “change for the better,” kaizen embodies the philosophy of continuous, incremental enhancement. This concept gained fame through Japanese automakers, but its spirit applies equally to individual artisans and large factory floors. The core belief is that nothing is ever perfect or complete. There is always room for improvement, however slight. A shokunin doesn’t simply master a technique and repeat it for decades; they constantly seek tiny refinements to make their work marginally better every day. It might be a subtle change in the chisel’s angle, a small tweak to a recipe, or a more efficient organization of tools. These adjustments may be barely noticeable on their own, but accumulated over a lifetime—or generations—they result in astonishing refinement. This isn’t about big, disruptive breakthroughs; it’s the patient, humble daily effort to perfect one’s craft. It’s a mindset that rejects complacency. The moment you believe your craft is perfected is when you begin to decline. This tireless pursuit of steady improvement ensures skills are not only preserved but sharpened and enhanced with each new generation.

The Social Blueprint: Why Did This Vibe Even Happen Here?

This intense philosophy of making things didn’t simply emerge out of nowhere; it’s no accident. Mono-zukuri is the outcome of Japan’s distinct and unique blend of geography, history, and social structure. To truly understand why this culture of craftsmanship runs so deep, one must examine the historical pressures and social norms that shaped it over centuries. It’s a story of isolation, scarcity, and the influence of the group—all combining to create the ideal environment for this way of thinking.

An Island Nation’s Resourcefulness (and Anxiety)

First, consider geography. Japan is an island nation—mountainous, prone to earthquakes, volcanoes, and typhoons, with historically limited natural resources. This reality has forged a particular mindset in the national consciousness for centuries. When resources like wood, metal, or fertile land are scarce, you learn not to waste them. This cultivated a deeply ingrained culture of mottainai (勿体無い), a term expressing guilt and regret over waste. It’s the feeling you get seeing food thrown away or a useful object discarded. This mentality is more than frugality; it’s almost a spiritual conviction that wasting nature’s blessings is wrong. This mottainai spirit directly feeds Mono-zukuri. With limited precious materials, you make sure to use them well. You don’t produce disposable, flimsy goods—you create something beautiful, functional, and most importantly, durable. You craft items meant to last, be repaired, and cherished across generations. This emphasis on durability and quality is not merely an aesthetic choice; it’s a survival strategy born from scarcity and environmental fragility. It’s a form of respect for limited resources, transforming them into objects of enduring value.

The Edo Period: A Pressure Cooker of Craft

History plays a crucial role, particularly during the Edo Period (1603–1868). At this time, Japan enforced sakoku (鎖国), a “closed country” policy that lasted over 200 years, severely limiting foreign trade and travel. While this had disadvantages, it fostered a unique environment for craftsmanship. With a long era of peace and a stable, rigid social hierarchy, artisans and craftspeople had the time to focus and refine their skills without outside disruption or influence. This peaceful isolation acted like a pressure cooker. Local domains, ruled by daimyo lords, competed not only militarily but also culturally and artistically. This rivalry led regions to specialize intensely in particular crafts: Tsubame-Sanjo in metalworking, Arita in porcelain, Sabae in eyeglasses, Seki in blades. This strong local pride and competition elevated the quality and sophistication of crafts to remarkable levels. Artisans weren’t competing on a global market but perfecting their craft for their community and lord. This extended period of focused development explains why many Japanese crafts showcase such profound technique and distinct regional identity.

The Group Over the Individual

Lastly, understanding Japan requires appreciating the importance of the group. Compared to more individualistic Western cultures, Japanese society traditionally emphasizes collective harmony and responsibility. Identity is deeply connected to one’s groups—family, school, company, town—and one’s actions represent that collective. This social structure powerfully motivates quality in Mono-zukuri. Shoddy workmanship is not just a personal failure; it brings shame (haji) to the workshop, family, and community. Conversely, producing exceptional quality honors the entire group. This shared responsibility creates strong social pressure to uphold extremely high standards. Everyone is accountable to everyone else. The reputation of the team, the company, and the “Made in Japan” label itself is at stake with every product leaving the workshop. This contrasts sharply with a culture where an individual might cut corners if they think they can avoid detection. Here, the watchful eyes of the group and collective honor take precedence. This deep sense of shared purpose is one of the most powerful and often unseen foundations supporting the philosophy of Mono-zukuri.

Mono-zukuri in the Wild: Where You Can Actually Feel It

Alright, so we’ve covered theory, history, and philosophy. But where can you actually see and experience these ideas in real life, beyond the polished museum displays? The great thing about Mono-zukuri is that it’s not some highbrow concept confined to galleries. It’s everywhere, deeply embedded in everyday life. You just need to know where to look. Instead of following a typical tourist checklist, think of these places as dynamic, living case studies where the philosophy comes alive.

The Stationery Store: A Tiny World of Kodawari

For a quick, hands-on introduction to Mono-zukuri, set aside the temples for a moment and visit a large stationery store like Itoya in Ginza or Tokyu Hands. Here, the dedication to detail and user experience shines brightly and is fully accessible. Grab a simple ballpoint pen from a brand like Pilot or Uni. It may cost just a dollar or two, but notice the fine points. Feel the balance in your hand. Observe the smooth engineering of the click mechanism—it’s satisfying, not cheap. Then write with it. The ink flows flawlessly from your very first stroke. This is no coincidence. Engineers devoted years to perfecting that ink and the ballpoint tip. Now look around. You’ll find notebooks with paper specially crafted to handle fountain pens, preventing feathering. You’ll see erasers designed to lift specific pencil leads with minimal smudging. You’ll find staplers engineered to require 50% less force. This is kodawari in its purest form, applied to everyday objects. It’s a world of micro-innovations fueled by the belief that even the simplest daily tool deserves perfection. It’s Mono-zukuri for everyone.

The Depachika: Culinary Artistry

Another incredible place to experience Mono-zukuri is in a depachika, the expansive, often bustling food hall beneath any large department store. This is no ordinary mall food court; it’s a dazzling stage of edible craftsmanship. The first thing you notice is the presentation. Strawberries aren’t just tossed into a plastic container; they’re nestled in cushioned boxes like precious gems, each one perfectly shaped, colored, and sized. Take a look at the bento boxes. Every ingredient, from the delicately cut carrot flower to the precisely arranged piece of fish, is placed with the care of a landscape gardener. This isn’t just about aesthetics; it reflects a profound respect for both the food and the person who will eat it. Chat with the vendors. The senbei (rice cracker) seller might be the fifth generation in their family to use the same slow charcoal-grilling technique. The confectioner crafting wagashi (traditional sweets) changes seasonal designs to capture the fleeting beauty of cherry blossoms or autumn leaves in sugar and bean paste. The depachika reveals that the Mono-zukuri spirit isn’t only for lasting goods—it’s applied with equal passion and focus to things meant to be consumed and savored in a single perfect moment.

Tsubame-Sanjo: An Entire Town as a Factory

To witness the philosophy on a larger scale, visit a place like Tsubame-Sanjo in Niigata Prefecture, which I described earlier. This area isn’t a charming tourist spot filled with old wooden houses. It’s raw and industrial, a vibrant hub of ongoing craftsmanship. The air hums with machinery. The region is world-renowned for producing some of the finest metalware—kitchen knives, cutlery, pots, pans, and professional tools. But what’s remarkable is how it’s made. It’s not one massive factory. Instead, it’s an extensive, interconnected network of hundreds of small, family-run workshops, each hyper-focused on one manufacturing step. One workshop only forges raw steel. Another strictly grinds blades. A third handles polishing. A fourth attaches wooden handles. Each workshop masters its tiny, specific task with a level of kodawari that would be impossible in a large, generalized factory. They collaborate, passing the item from one specialist to the next, each adding their expert touch. The whole town operates like one vast, decentralized collective of artisans. If you can, visit during an “Open Factory” event when many workshops welcome the public. Witnessing this intricate chain of specialized skills at work is a powerful experience. It’s Mono-zukuri’s social structure made tangible.

The Flip Side: The Not-So-Glamorous Reality

It’s easy to idealize Mono-zukuri. The tales of devoted artisans and flawless products are captivating. However, it would be misleading to suggest it’s all about beautiful cherry blossoms and serene concentration. Like any intense cultural philosophy, it has its darker aspects. The very qualities that produce exceptional quality can also result in rigidity, impose immense pressure on individuals, and, in extreme cases, cause dramatic failures. To truly understand it, you must examine the cracks in the elegant ceramic bowl.

Resistance to Change and Crippling Perfectionism

The profound respect for tradition and the craftsman’s lifelong commitment to a single technique can be a double-edged sword. The belief that “this is how it has always been done because it is the best way” can strongly uphold quality. Yet, it can also hinder radical innovation and adaptability. In a rapidly changing world, this cautious, incremental mindset can be a serious drawback. While a German company might innovate by completely reimagining a product, a Japanese company might spend the same time achieving just a 1% improvement on an existing model. This paralyzing perfectionism can also cause excessively long development periods and high costs for products where “good enough” would have sufficed. Sometimes, speed to market matters more than reaching the ultimate peak of quality—a lesson some traditional Japanese industries have struggled to embrace.

The Human Cost

The craftsman’s image is one of noble sacrifice, but we must ask: at what price? The journey to mastery is often harsh. The apprenticeship system, though effective, relies on years of low wages, grueling hours, and a hierarchical structure that leaves little space for personal expression or work-life balance. It demands a level of dedication increasingly misaligned with the ambitions of younger generations. This has triggered a significant succession crisis across Japan. Many traditional craft workshops face extinction because the next generation shows little interest in inheriting the family trade. Witnessing the toll on their parents, they pursue different, often more stable and less demanding careers. The very system that forged this incredible legacy of craftsmanship now threatens its own survival. The pool of young people ready to devote their entire lives to a single, demanding craft is dwindling, posing a clear and imminent danger to many of these traditions.

When the System Fails: The Scandals

Here is the most uncomfortable truth. The intense social pressure to preserve a reputation for impeccable quality can, ironically, foster conditions where cheating becomes a temptation. When absolute perfection is demanded and, for some reason, that standard can’t be met, the pressure to falsify results can be overwhelming. In recent years, Japan has been shaken by several prominent corporate scandals in which some of its most renowned and iconic manufacturing firms—the very embodiments of Mono-zukuri—were found to have falsified quality data, sometimes over decades. Companies in steel, automotive parts, and chemicals were discovered to have shipped products failing to meet required standards. This is the worst nightmare for a culture founded on trust and reputation. It demonstrates that when the burden of upholding an ideal becomes unbearable, the system can collapse in spectacular ways. It’s a sobering reminder that Mono-zukuri is an ideal pursued by imperfect humans, who sometimes find the weight of that ideal too heavy to bear.

So, What’s the Takeaway?

So, after everything, what’s the final take on Mono-zukuri? The important point is that it’s not merely a catchy marketing phrase or just another word for “high quality.” It’s a genuine, deeply rooted cultural philosophy—a whole vibe, a complex and sometimes contradictory set of beliefs about work, materials, and life itself, shaped by Japan’s unique historical and social journey. It’s a worldview founded on the shokunin spirit of lifelong dedication, the intense kodawari that pursues perfection in even the smallest details, and the continuous kaizen cycle—the daily effort to improve bit by bit.

This philosophy explains why a simple Japanese object can feel fundamentally distinct and profoundly satisfying to hold and use. It’s not just an inanimate thing; it carries the intention, struggle, pride, and accumulated wisdom of its maker. It’s infused with a story. When you hold a perfectly balanced pen or a hand-forged kitchen knife, you’re connecting with a culture that believes the act of making things is a path to self-improvement, a way to contribute to the community, and a method of embedding a piece of the human spirit into the material world.

It’s not flawless. It can be rigid and demanding, with a darker side. But at its best, Mono-zukuri is a powerful statement in a world dominated by disposability. It’s a commitment to the idea that some things deserve to be done slowly, with great care, and wholehearted dedication. It’s not about being “the best” in a competitive sense, but about being true to the process, the material, and an ideal. And once you grasp that, once you truly understand that vibe, you’ll begin to see it everywhere in Japan—not just in what they make, but in how they do almost everything.