Yo, let’s have a real talk. Picture this: you’re ghosting the neon chaos of Tokyo, ditching the temple crowds in Kyoto, and straight-up teleporting into a woodblock print from the 17th century. We’re not talking about a museum, fam. We’re talking about the Nakasendo Trail, an ancient highway carved through the heart of Japan’s central mountains, a place where time isn’t just a concept, it’s a full-on vibe. This isn’t your average hike; it’s a time-travel flex, a deep dive into the soul of feudal Japan. The Kiso Valley, or Kisoji, is the VIP section of this legendary route, a stretch so perfectly preserved it feels like the shoguns and samurai could stomp around the corner at any second. It’s where the whispers of the past aren’t just whispers; they’re the roaring sound of a mountain stream, the creak of a wooden waterwheel, the taste of woodsmoke in the crisp alpine air. This journey is about trading your frantic doomscrolling for the rhythmic thud of your own footsteps on centuries-old stone. It’s about logging off and plugging into a network of history, nature, and culture that’s been live for hundreds of years. This, my friends, is the real Japan, unfiltered and absolutely epic. Get ready to walk the walk, because the Nakasendo is calling, and trust me, you’re gonna want to pick up.

To fully immerse yourself in this historic journey, discover more about hiking the Nakasendo Trail through the Kiso Valley.

Dropping In: The Vibe of the Ancient Highway

From a historian’s viewpoint, the term ‘atmosphere’ can often seem frustratingly elusive, yet on the Nakasendo, it becomes a tangible presence. It’s the first thing that strikes you when you step off the bus in a town like Magome or Tsumago. The air itself feels altered—thinner, cleaner, and carrying the subtle, sweet scent of Kiso hinoki cypress. The ambient noise of the 21st century simply fades away. There are no pachinko parlors or blaring convenience store jingles. Instead, you hear the rhythmic flow of water coursing through narrow channels alongside the cobbled paths, a system designed centuries ago for both beauty and fire prevention. You hear birdsong unlike anything you’ve heard before, the rustling of leaves in a breeze that seems to come straight from the peak of Mount Ontake, and the gentle clacking of wooden geta sandals on stone. The entire scene is a sensory lesson in tranquility.

Visually, it’s stunning. The post towns, or shukubamachi as they are properly called, are not reconstructions but carefully preserved communities of wood and stone. The buildings, with their dark-stained lattice fronts (koshi) and gracefully curved tiled roofs, cluster closely along the main street. There is a deep sense of continuity here. You’re not simply looking at historic structures; you’re walking through a living community that has deliberately resisted the unrelenting advance of modernity. In Tsumago, for example, a local charter was introduced in the 1970s with a straightforward but radical rule: do not sell, do not rent, do not demolish. This collective effort means you won’t find a single power line or television antenna disrupting the Edo-period skyline. It’s a commitment that is, quite honestly, breathtaking. This is not a theme park. It’s an authentic shift in atmosphere—a quiet rebellion against the disposable nature of modern life. It’s a place that insists you slow down, to observe the details—the intricate wooden carvings on a shopfront, the seasonal flowers arranged simply in a vase, the steam rising from freshly grilled gohei mochi. You start moving at a different tempo, an Edo-period rhythm, and that, perhaps, is the most profound experience of all.

The OG Influencers: Samurai, Merchants, and Princesses

To truly appreciate the stones you walk upon, you must understand who traveled them before you. The Nakasendo, meaning the ‘Central Mountain Route,’ was one of the two main highways linking the shogun’s capital Edo (modern-day Tokyo) with the imperial capital Kyoto during the Tokugawa period (1603-1868). While the coastal Tokaido route was better known and more heavily traveled, the Nakasendo served as its rugged, mountainous counterpart. This journey stretched about 534 kilometers and featured 69 post stations offering lodging, food, and fresh horses to travelers.

But who were these travelers? The range of people was remarkably diverse. At the top of the social hierarchy were the daimyo, the feudal lords. Under the shogun’s sankin-kōtai (alternate attendance) system, these lords had to spend every other year in Edo—a shrewd political strategy to drain their resources and keep them under the shogun’s control. Their processions were grand displays of power, with hundreds or even thousands of samurai retainers, porters, and officials winding through the mountain passes. Picture the immense logistical coordination, the clanking of armor, and the fluttering clan banners against the backdrop of the Kiso forests. It was the ultimate demonstration of authority.

Yet, the road was not reserved solely for the elite. It was also a vital artery of commerce. Merchants transported goods such as silk, lacquerware, and sake between the country’s two major centers. Pilgrims clad in white made their way to sacred places like the Ise Grand Shrine or Zenko-ji Temple, their journeys symbolizing devotion. The travelers included itinerant monks, government officials on urgent duties, and even artists and poets like the renowned Matsuo Basho, who found inspiration in the landscapes and human stories along the route.

Perhaps the most moving tale is that of Princess Kazu, or Kazunomiya, sister to Emperor Komei. In 1861, in a desperate political effort to unite the Imperial Court and the Shogunate against advancing Western powers, she was sent from Kyoto to Edo to marry Shogun Iemochi. Her procession along the Nakasendo was a monumental and sorrowful event, involving tens of thousands of people. One can only imagine her thoughts as she traveled this remote, challenging path, leaving behind her home and life for a future she had not chosen. When you walk the trail, especially through the more somber, forested sections, you are literally following in her footsteps. This historical context transforms a simple hike into a profound pilgrimage. No exaggeration—the history here is so dense you can feel it with every step.

The Main Event: Trekking Magome to Tsumago

Alright, let’s dive into the heart of it—the trail section that perfectly embodies the Nakasendo experience: the eight-kilometer hike between Magome-juku and Tsumago-juku. This is undoubtedly the most popular and accessible segment of the entire Kiso Valley trail system, and for good reason. It offers an ideal mix of physical activity, breathtaking nature, and cultural immersion. It’s the highlight, the main quest.

Starting in Magome-juku

Most people prefer to begin in Magome and hike toward Tsumago, a choice I fully support since it turns the initial, steeper climb into a downhill stroll on the way. Magome stands out among the post towns. Unlike the others, which typically sit on flat valley floors, Magome is perched on a steep, dramatic incline. Its main street is a 600-meter stone-paved slope, lined on both sides with beautifully restored inns, souvenir shops offering intricate wooden crafts, teahouses, and noodle restaurants. The constant sound of flowing water runs through wooden aqueducts, powering several large, creaking waterwheels—a strikingly picturesque scene, almost painfully beautiful. Before setting off on your hike, take some time to explore. Visit the Toson Memorial Museum, dedicated to the Meiji-era writer Shimazaki Toson, whose epic novel “Before the Dawn” is set here, vividly portraying the turmoil at the end of the samurai era. Grab a gohei mochi for a pre-hike energy boost. The atmosphere is lively yet deeply respectful of its heritage. It’s an ideal place to start your journey.

On the Trail

The trail out of Magome begins gently, passing by the old noticeboard (kosatsuba), where the shogun’s decrees were once posted for public view. Soon, you are surrounded by forest. The path alternates between stretches of original ishidatami cobblestones, laid centuries ago to prevent erosion, and compacted dirt trails. The stones can be slippery, particularly after rain, so sturdy footwear is essential. Along the way, you’ll spot bells hanging at intervals—these are bear bells (kuma-yoke no suzu). Asiatic black bears inhabit these mountains, and though sightings are extremely rare, tradition holds that ringing the bell loudly alerts bears to your presence and keeps them away. It’s a mild thrill and a clear reminder that you’re a guest in a wild environment.

About halfway through, you’ll come across a true treasure: Tateba-chaya, a traditional rest house. This is not a commercial establishment but a simple wooden structure run by local volunteers who welcome you inside, offer you a seat by the crackling hearth (irori), and serve complimentary hot tea and pickled vegetables. This thoughtful hospitality, or omotenashi, harkens back to a time when such kindness was vital for weary travelers. Sitting there, sipping tea and chatting with the elderly host by the fire, becomes a cherished memory.

Further along, the trail brings you to the Odaki and Medaki waterfalls—the ‘Male’ and ‘Female’ falls. The sound of rushing water grows louder, with a cool mist in the air. It’s an ideal spot to pause, catch your breath, and admire the raw, untamed beauty of the Kiso region. The entire hike takes about two to three hours at a leisurely pace, giving you plenty of time for photographs and to soak in the scenery.

Arriving in Tsumago-juku

The final descent into Tsumago feels like the grand finale. Emerging from the forest, you’ll see the impeccably preserved town nestled in the valley. If Magome is picturesque, Tsumago is like a living historical document. It was the first town in Japan to undertake major preservation efforts, and its dedication to authenticity is remarkable. Utility wires are buried, modern signage is banned, and the dark wooden inns and houses absorb sunlight, casting a warm, nostalgic glow. Be sure to explore the Wakihonjin Okuya, a former ‘sub-honjin’ inn used by retainers of high-ranking officials, now a museum. Its detailed hinoki cypress woodwork and refined design provide a vivid glimpse into Edo-period aesthetics. Arriving in Tsumago doesn’t feel like the end of a hike—it feels like completing a journey through time. The sense of achievement is real, and the reward is one of Japan’s most beautiful historical towns.

Beyond the Hype: Exploring More of the Kiso Valley

While the Magome-Tsumago trail is undeniably the highlight, to fully appreciate the Kiso Valley, you need to explore beyond it. Focusing solely on that section is like repeatedly playing a band’s greatest hit without ever delving into the deeper tracks on their albums. The rest of the Kisoji provides equally, if not more, rewarding experiences for those ready to put in the effort.

Narai-juku: The King of Post Towns

Travel north from Tsumago, and you’ll eventually arrive at Narai-juku, a place that truly earns its nickname, “Narai of a Thousand Houses” (Narai senken). It is the longest post town in the Kiso Valley, stretching over a kilometer. Its scale is impressive; whereas Tsumago feels cozy and contained, Narai comes across as grand and prosperous. Historically, it was one of the wealthiest post towns along the entire Nakasendo, a fact reflected in its wider streets and larger, more imposing inns. Many buildings remain private homes or active businesses, including several famous lacquerware shops for which the region is renowned. You could easily spend hours exploring shops, visiting small museums like the Nakamura Residence, and admiring the well-preserved townscape. Narai is also the starting point for one of the most challenging and historically significant hikes on the route: the crossing of the Torii Pass to Yabuhara. It’s truly a next-level adventure.

The Torii Pass: A Spiritual Ascent

For serious hikers, the trek from Narai to Yabuhara via the Torii Pass is an absolute must. This stretch is steeper, more rugged, and far less crowded than the Magome-Tsumago path. The pass itself, standing at 1,197 meters, was a daunting challenge for travelers during the Edo period. The ascent through dense forest feels ancient and untouched. At the summit, you’re greeted by a collection of stone monuments and a large Shinto torii gate, from which the pass takes its name. This area has strong ties to the Ontake faith, a syncretic folk religion centered on the sacred Mount Ontake, visible on clear days. Reaching the summit feels like a genuine accomplishment—both spiritual and physical. The profound solitude and historical significance weigh heavily here, making you truly feel off the beaten path.

Kiso-Fukushima: A Hub of History and Culture

Unlike the preserved post towns of Tsumago or Narai, Kiso-Fukushima is a larger, living town that served as a major administrative center on the Nakasendo. It serves as an excellent base for exploring the wider valley. Its most notable historical site is the Fukushima Checkpoint (Fukushima Sekisho), one of only two checkpoints along the Nakasendo (the other is in Usui). Checkpoints were intimidating places, run by strict officials charged with upholding the shogun’s authority. Their motto was iri-deppo ni de-onna—‘inspect guns coming in and women going out.’ They searched for smuggled firearms that could incite rebellion and for the wives and daughters of daimyo, essentially political hostages in Edo who might attempt to flee. The reconstructed checkpoint museum offers a chilling glimpse into the Tokugawa regime’s strict control. Kiso-Fukushima is also home to Kozen-ji Temple, which boasts the largest dry landscape rock garden in Asia. This expansive, meditative space provides a serene contrast to the demands of the trail.

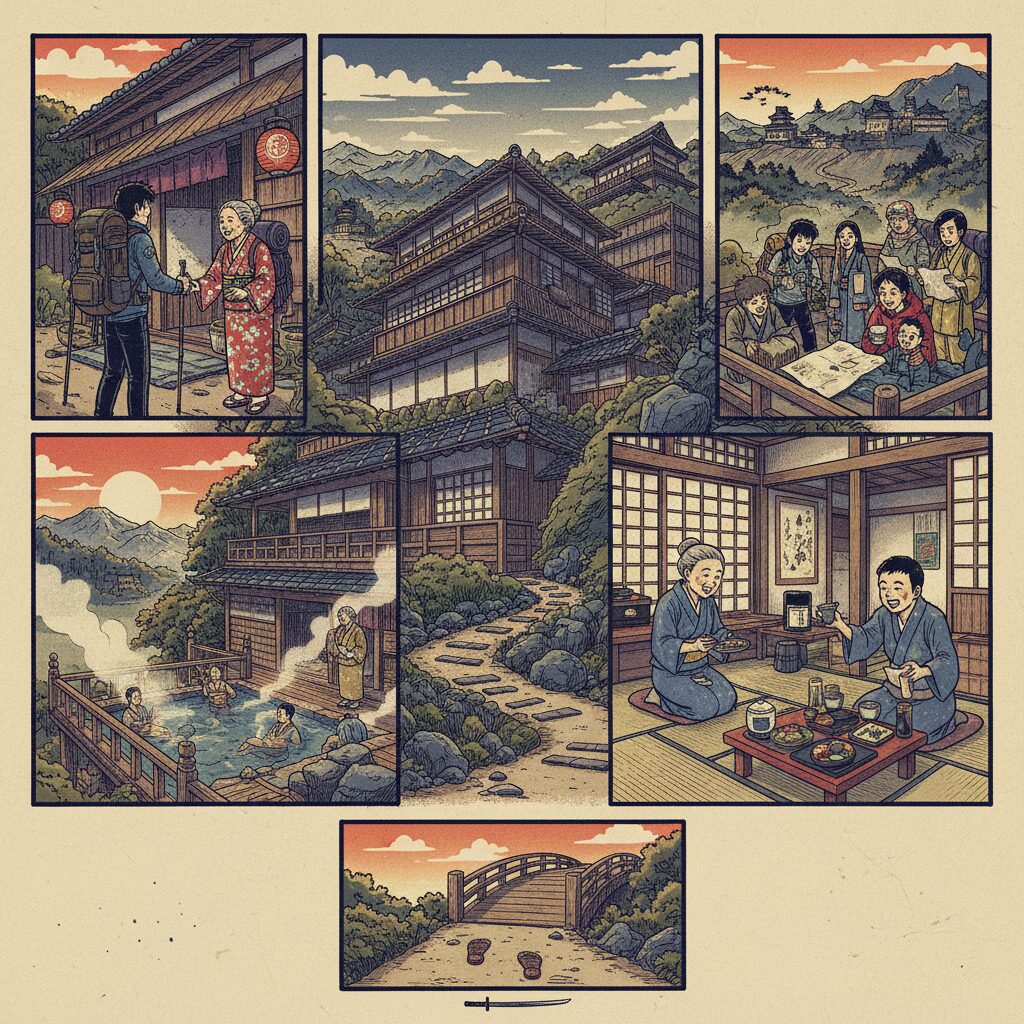

Level Up Your Stay: Minshuku and Ryokan Life

The Nakasendo experience is essentially incomplete without an overnight stay in a traditional Japanese inn. This goes beyond simply finding a place to sleep; it is a vital part of immersing yourself in the culture. Typically, your choice will come down to two types of accommodations: a minshuku or a ryokan.

A minshuku offers a more rustic and intimate atmosphere. These family-run guesthouses are often situated within the owners’ own homes. The experience is personal and deeply authentic. Hosts greet you warmly, prepare your meals, and attend to your needs. While the facilities might be more basic, often featuring shared bathrooms, the hospitality and warmth are unmatched. It feels less like being a tourist and more like being a welcomed guest in a Japanese household. Meals are home-cooked, showcasing local seasonal ingredients and served with pride, providing a genuine opportunity to connect with locals.

In contrast, a ryokan is a more formal, traditional inn. Although still centered on hospitality, they tend to be larger and more service-focused, staffed by dedicated personnel. The experience is typically more polished. Guests receive a yukata (cotton robe) to wear around the inn and to the baths. Many ryokan in this mountainous region feature onsen (hot spring) baths, ideal for relaxing sore muscles after a day of hiking. The highlight of a ryokan stay is the evening meal: a multi-course kaiseki dinner, which is more than just food—it is culinary artistry. A sequence of small, exquisitely prepared dishes, each highlighting seasonal ingredients and careful craftsmanship, is served either in your room or a communal dining area. From delicate sashimi to grilled river fish and simmered mountain vegetables, it is a feast for the senses. Waking up to an equally elaborate traditional Japanese breakfast—featuring rice, miso soup, grilled fish, tamagoyaki omelet, and various pickles—is the perfect way to prepare for another day on the trail. Sleeping on a futon laid out on a tatami mat floor while listening to the night sounds outside your paper screen window creates a lasting and unforgettable experience.

Fueling the Journey: What to Eat in the Kiso Valley

A journey through the Kiso Valley is as much a culinary adventure as it is a physical one. The food here is rustic, hearty, and deeply tied to the surrounding mountains. Forget the sushi and ramen of big cities; this is the soul food of the Japanese Alps.

Gohei Mochi

If the Kiso Valley had a mascot, it would undoubtedly be gohei mochi. You’ll see it, smell it, and absolutely have to try it. This isn’t the soft, round mochi you might be familiar with. Instead, it’s a fistful of partially pounded rice, shaped onto a flat wooden skewer resembling a traditional Shinto offering, then grilled over an open flame. The true magic lies in the sauce: a thick, rich glaze made from miso, walnuts, sesame, and a hint of sugar. The result is a savory, sweet, smoky, and nutty flavor explosion with a delightfully chewy texture. It’s the ultimate trail snack, available from small stands in every post town. No excuses — you have to taste it.

Shinshu Soba

The mountainous terrain and volcanic soil of Nagano Prefecture (historically known as Shinshu) provide ideal conditions for growing buckwheat, the essential ingredient in soba noodles. This region is a haven for soba enthusiasts. The noodles here are fresh, handmade, and boast a wonderfully nutty, earthy flavor. You can enjoy them cold (zaru soba), served on a bamboo tray with chilled dipping sauce, wasabi, and green onions—a refreshing option after a hike. Alternatively, you can have them hot (kake soba) in a savory dashi broth, often topped with wild mountain vegetables (sansai) or duck (kamo nanban). Eating authentic Shinshu soba is an essential part of the Kiso experience.

Mountain Bounty and River Fish

Local cuisine heavily features the bounty of the mountains and rivers. Sansai, or wild mountain vegetables, are a staple, appearing in tempura, simmered dishes, and as side dishes. Fiddlehead ferns (kogomi), bamboo shoots (takenoko), and various mountain roots provide unique, slightly bitter flavors that define rural Japanese cooking. The clear, cold streams of the Kiso River are home to delicious freshwater fish like iwana (char) and ayu (sweetfish). They’re typically prepared by salting and grilling over charcoal (shioyaki), a method that crisps the skin perfectly while keeping the flesh flaky and sweet.

Hoba Miso

This is a truly distinctive regional dish. A large, dried magnolia leaf (hoba) serves as a miniature grill. A dollop of savory miso paste, often mixed with green onions, mushrooms, and other vegetables, is spread on the leaf and cooked over a small charcoal brazier right at your table. The leaf imparts a subtle, smoky aroma to the bubbling miso. You then scoop up the delicious, caramelized paste with your rice. It’s an interactive, fragrant, and deeply satisfying dish that perfectly embodies the rustic ingenuity of mountain cuisine.

The Logistics Lowdown: Getting There and Around

Navigating your way to and through the Kiso Valley might appear challenging, but Japan’s renowned public transport system makes it surprisingly easy. Here’s the essential information you need to plan your trip.

Access from Major Cities

The primary route to reach the Kiso Valley is the JR Chuo Main Line, which links Nagoya in the south to Nagano and ultimately Tokyo in the north.

From Tokyo: The fastest way is to take the Tokaido Shinkansen (bullet train) to Nagoya (approximately 1 hour 40 minutes), then transfer to the JR Limited Express Shinano train heading toward Nagano. This is the main train serving the Kiso Valley.

From Nagoya: This is the most direct entrance. Board the JR Limited Express Shinano. The trip to the valley’s southern edge (Nakatsugawa Station for Magome) takes about 50 minutes. Traveling to the northern end (Kiso-Fukushima or Narai) is roughly 1 hour 20 minutes.

From Kyoto/Osaka: Take the Tokaido Shinkansen to Nagoya and follow the directions above. The entire journey takes about 2 to 2.5 hours.

Getting Around the Valley

Once you’re inside the valley, a mix of local trains and buses will be your most reliable options. The JR Chuo Line runs local services stopping at all the small stations among the main towns. For the Magome-Tsumago hike, the key stations are Nakatsugawa (for Magome) and Nagiso (for Tsumago). Buses connect these train stations to their respective post towns. A bus from Nakatsugawa Station to Magome-juku takes about 25 minutes. From Tsumago, you can catch a bus to Nagiso Station (about 10 minutes) to continue your journey. Direct buses also run between Magome and Tsumago for those who prefer not to hike the entire distance.

One of the most convenient services is the baggage forwarding service (takkyubin), which operates between the tourist information centers in Magome and Tsumago. For a small fee, you can drop off your luggage in the morning and have it waiting for you at the other side. This service is a game-changer, allowing you to hike light with just a small daypack. It’s peak convenience.

Best Time to Go

The Kiso Valley is stunning throughout the year, with each season offering a unique experience.

Spring (April-May): The weather is mild, and the valley is vibrant with cherry blossoms and fresh green foliage. It’s a season of renewal and is generally less crowded than autumn.

Summer (June-August): The scenery is lush and vividly green. However, it can be hot and humid, with June and July marking the rainy (tsuyu) season. Be prepared for rain and possible trail disruptions.

Autumn (October-November): Undoubtedly the best time to visit. The weather is cool and crisp, ideal for hiking. The autumn foliage (koyo) is breathtaking, with the mountainsides displaying fiery reds, oranges, and yellows. It’s the most popular season, so book accommodations well in advance.

Winter (December-February): A quieter, more peaceful experience. Snow often blankets the towns and trails, creating a magical, monochrome landscape. It’s beautiful but be cautious: hiking can be dangerous, some trails may close, and many inns and shops operate on limited hours or close entirely. This season suits the well-prepared and those seeking solitude.

The Final Stretch: Leaving Your Footprint on History

Walking the Nakasendo is more than just a checklist item on a Japan itinerary. It serves as an antidote to the fast pace of the modern world, a physical and mental reset button. With every step on the worn cobblestones and every breath of crisp mountain air, you connect with something ancient and enduring. You aren’t merely observing history from behind a velvet rope; you are actively partaking in it, adding your own fleeting story to a narrative that has been unfolding for centuries. The journey strips away the unnecessary, leaving you with the simple, profound rhythm of walking, eating, and sleeping. It reminds you of the beauty in simplicity—a shared cup of tea, the warmth of a hearth fire, the taste of rice grown in a nearby paddy. You leave the Kiso Valley not just with photos, but with a feeling—a sense of peace, a deeper appreciation for craftsmanship and preservation, and perhaps even slightly sore calf muscles. So go ahead, take the hike. Walk in the footsteps of samurai and princesses. Find your own rhythm on this ancient road. I promise, you won’t regret it.