Yo, what’s the vibe? Shun Ogawa here, dropping in to talk about a place that’s so legit, it feels like you’ve glitched into another century. We’re not talking about some slick, modern museum with sterile glass cases. Nah, we’re diving headfirst into the real deal, a place where the air itself feels thick with stories, drama, and the echoes of thunderous applause from ages past. Get ready, because we’re heading to Kotohira in Kagawa Prefecture, on the island of Shikoku, to explore the one and only Kanamaru-za, Japan’s oldest surviving, complete kabuki theater. This isn’t just a building; it’s a living, breathing testament to the electric energy of Edo-period entertainment. Forget what you think you know about theaters. Kanamaru-za, officially known as the Konpira Grand Theatre, hits different. Built way back in 1835, this wooden masterpiece has seen it all, and stepping inside is less like a tour and more like a full-blown sensory download of Japanese cultural history. It’s the kind of place that’s low-key one of the most important cultural assets in the country, but it carries its legacy with a quiet, powerful grace. It’s here, nestled on the path to the legendary Kotohira-gu Shrine, that you can literally walk the boards, crawl beneath the stage, and feel the soul of kabuki in a way that’s impossible anywhere else. This is where the magic was, and still is, made. No cap, a visit here will rewire your brain and give you a whole new appreciation for the artistry and innovation of old-school Japan. It’s an emotional, or as we say, emoi, experience that connects you directly to the past. Before we get into the nitty-gritty of why this spot is an absolute must-see, get your bearings and check out where this legendary theater is located.

After immersing yourself in this historic theater, you can continue your cultural journey through Kagawa by embarking on a Sanuki udon pilgrimage to taste the region’s famous noodles.

The Vibe Check: Stepping into an Analog Wonderland

First, let’s discuss the atmosphere, because at Kanamaru-za, the ambiance is everything. The instant you slip off your shoes at the entrance and your socked feet meet the cool, weathered floorboards, the 21st century seems to vanish. It’s an immediate, profound transformation. Your senses awaken instantly. There’s the rich, earthy aroma of aged timber—cedar, cypress, and pine—that has absorbed nearly two centuries of humidity, seasonal changes, and human emotion. It’s a scent both soothing and invigorating, a fragrance steeped in history itself. Then your eyes adjust to the quality of the light. There are no harsh LEDs or spotlights here. Instead, natural light gently filters through the paper-covered shoji screens lining the walls, casting a warm, soft glow across the space. It creates a realm of subtle shadows and highlights, making you feel as if you have stepped into a living ukiyo-e woodblock print. The entire structure feels organic, handcrafted, and deeply human.

Unlike a modern theater, often designed to make you forget the building and focus solely on the stage, Kanamaru-za is an immersive environment. You are vividly aware of the space around you. You hear the soft creak of floorboards beneath your feet, the faint rustle of paper lanterns swaying in a stray breeze. When the theater is empty, a profound silence prevails, but it’s not a hollow stillness. It’s a resonant quiet, filled with the echoes of past performances—the booming voices of iconic actors, the sharp clap of wooden blocks signaling scene changes, the collective gasp of an audience witnessing a dramatic moment. You can almost feel the energy vibrating within the wooden pillars and beams.

The main auditorium is awe-inspiring. Rather than rows of individual seats, the floor is arranged into a grid of tatami-mat-covered boxes called masu-seki. These square enclosures, separated by low wooden railings, were where families or groups sat together on cushions, sharing food and sake while enjoying day-long performances. Looking out over this sea of masu-seki from the upper gallery, you can vividly picture the scene: a lively, vibrant social gathering, sharply contrasting with the hushed, reverent mood of Western theaters. It was loud, interactive, and communal. This was entertainment for the people, and the architecture reflects that democratic, celebratory spirit. The entire building is a tribute to an era before digital effects and amplification—a time when spectacle was created through raw ingenuity, human effort, and masterful design. This analog world is what makes Kanamaru-za so exceptional. It’s not a relic; it’s a fully operational piece of historical technology, and being inside it feels like a rare backstage pass to history.

The Main Event: Unpacking the On-Stage and Backstage Genius

So, what draws people from around the world to this tranquil corner of Shikoku? It’s because Kanamaru-za isn’t merely old; it’s a treasure trove of theatrical innovations that were truly groundbreaking in their era. This is where the magic happened, and when you visit on a non-performance day, you get to explore it all. It’s an access-all-areas experience that’s genuinely next level.

The Mawari-butai: The Original Revolving Stage

One of the most astonishing features is the mawari-butai, or revolving stage. This huge circular part of the stage floor can be rotated to enable quick, seamless scene changes. While a new set is arranged on the back half of the circle, the play continues on the front half. Then, at a signal, the whole thing spins, revealing an entirely new scene. It’s a theatrical technique that still amazes audiences today. But here’s the surprise: it’s completely human-powered. During a tour, you can actually go under the stage into the naraku (a word meaning “hell” or “abyss,” reflecting the dark, cramped space). Down there, you’ll see the enormous wooden turntable structure. Four large wooden push-bars extend from the center. This is where stagehands, in near-total darkness, would push with all their strength to rotate the massive stage above. Standing in that dark, cavernous space, you can sense the incredible physical effort needed to create the illusion and magic for the audience. It’s a powerful testament to human ingenuity at the heart of kabuki.

The Seri: Trap Doors for a Dramatic Drop-in

Another Edo-era stagecraft marvel is the seri, or trap doors. These function as elevators, simple yet effective, used to raise actors onto the stage for a surprise entrance or lower them for a dramatic exit. Kanamaru-za has several of these, all operated by hand. Some were straightforward platforms lifted by a team of strong stagehands, while others used a clever cantilever system. Imagine a powerful samurai suddenly emerging from the earth, or a ghost slowly disappearing into the floor. This technology made that possible. Seeing these mechanisms up close and standing on the very platforms where legendary actors once made their grand appearances is an unforgettable experience. It demystifies the magic just enough to deepen your appreciation for the skill and coordination of the entire theater troupe, from the performers to the unseen heroes working below.

The Hanamichi: The Flower Path to Glory

Extending from the main stage, straight through the audience on the left side, is the hanamichi, or “flower path.” It’s more than just an aisle; it’s a secondary stage, a runway that places actors right among the spectators. The hanamichi is iconic in kabuki and is used for some of the most dramatic and pivotal entrances and exits in the repertoire. A hero returning from battle, a tragic heroine making her final passage, a villain swaggering onto the scene—these moments happen just inches from the audience. This closeness created an intense sense of intimacy and excitement. It broke the fourth wall long before the term existed, making the audience feel part of the action. You can walk the full length of the hanamichi at Kanamaru-za, imagining the roar of the crowd and the weight of a thousand eyes on you. It’s a powerful journey that connects you to the core of the kabuki experience.

The Natural World of Light and Sound

Kanamaru-za was built before the age of electricity. This limitation sparked a unique kind of creativity. The lighting was a dynamic play of natural light from the side windows and the flickering glow of hundreds of candles. The side shoji screens could be opened or closed to adjust the daylight, shifting the mood from bright afternoon scenes to dusky twilight moments. For evening or interior scenes, candles provided a soft, dramatic glow that made the actors’ colorful costumes and intricate makeup stand out. The acoustics are equally remarkable. The all-wood construction produces a warm, resonant sound. Actors had to project their voices to fill the hall, and their stylized speech patterns were partly designed to ensure clarity. The sharp thwack of wooden clappers, called ki, used to signal the start of a play or emphasize dramatic moments, would have echoed powerfully throughout the space. Experiencing this environment helps you understand how Kanamaru-za’s very architecture shaped kabuki as an art form.

The Backstory: A History That Hits Different

To fully experience Kanamaru-za, you need to grasp its epic story—a saga of glory, decline, and an astonishing revival. The theater’s history is as dramatic as any play staged within its walls and is deeply woven into the spiritual and cultural fabric of Kotohira town.

Birth of a Star: Entertainment for Pilgrims

The story starts in the Edo period. Kotohira was—and remains—home to the significant Kotohira-gu Shrine, also called Konpira-san. This shrine, dedicated to the guardian deity of seafarers, was among Japan’s most popular pilgrimage sites. People from all walks of life, from samurai to merchants, undertook the difficult journey to pray for safe voyages. After climbing the steep mountain path to the shrine, these pilgrims sought entertainment. In response, Kanamaru-za was built in 1835 to serve them. Ideally located to attract crowds, it offered the era’s most popular entertainment: kabuki. The theater rapidly became a premier venue, drawing top actors and large audiences, securing its role as a cultural center.

The Fall and Forgotten Years

However, as times shifted, so did entertainment preferences. With the Meiji Restoration, the influx of Western culture, and later the rise of cinema in the 20th century, kabuki’s popularity declined. Kanamaru-za, like many traditional theaters, struggled. Its heyday faded, and the magnificent building was repurposed—painfully, as a movie theater. Its intricate stage machinery was hidden away, the masu-seki covered, and the spirit of the place seemed to dissolve. By mid-20th century, it had fallen into neglect and disrepair, a forgotten treasure gradually overtaken by time. It was at risk of disappearing forever, a tragic finale to a legendary legacy.

The Comeback Kid: A Legendary Restoration

Then came a miracle. In the 1970s, a movement emerged to save this invaluable cultural heritage. Architects, historians, and locals united. A detailed investigation uncovered something remarkable: beneath the movie theater’s modern floorboards lay the original mawari-butai and seri mechanisms, nearly intact. This was a priceless discovery. A major restoration project was launched, lasting four years and funded by government grants and public support. Skilled craftsmen, employing traditional methods and materials, painstakingly restored the theater to its Edo-period grandeur. This effort became one of the most ambitious and successful cultural restorations in modern Japan. The theater was slightly relocated to its current site and reopened in 1976, reborn and ready for a new chapter. In 1970, it had been designated a National Important Cultural Property, safeguarding its legacy for the future.

The Annual Revival: Shikoku Konpira Kabuki Oshibai

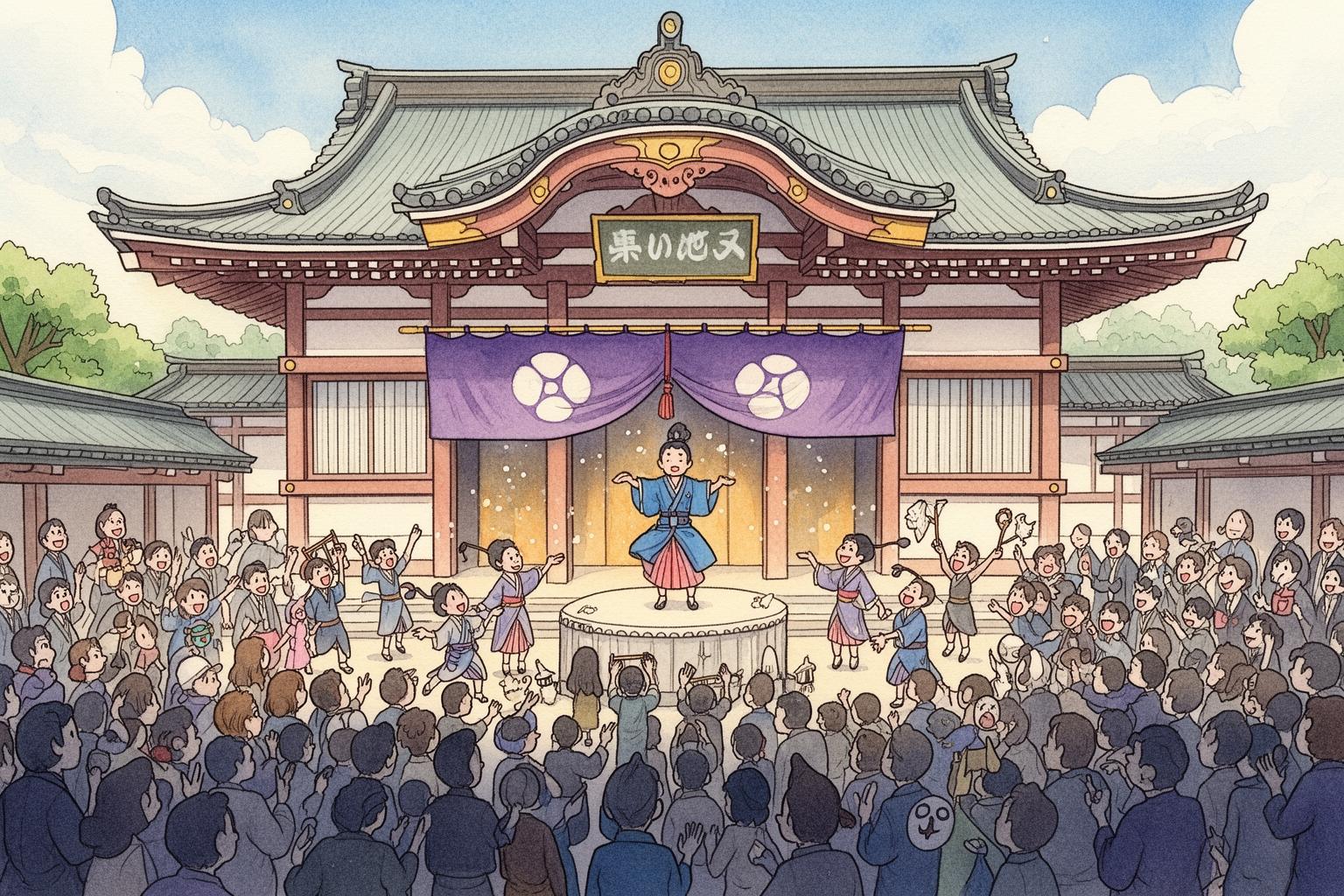

Restoration complete, but a theater is more than just a building—it needs performances. The true revival arrived in 1985 with the launch of the Shikoku Konpira Kabuki Oshibai. This annual festival, held every spring (usually in April), returned kabuki to its rightful home. Some of Japan’s most renowned kabuki actors, inspired by the theater’s history and unique atmosphere, embraced the event. They performed here, drawn by the chance to reconnect with the roots of their art. Today, this festival is among the most prestigious and highly sought-after in the kabuki world. For a few weeks each year, Kanamaru-za is no museum—it bursts back to life, filled with actors, musicians, and eager audiences. Paper lanterns glow, the aroma of bento fills the air, and the calls of kakegoe echo through the hall once again. It is a full-circle moment, a powerful tribute to the enduring magic of kabuki and the community that refused to let it fade away.

Kabuki 101: The Lowdown for First-Timers

If you’re new to kabuki, a performance might feel somewhat wild and overwhelming. However, knowing a few key elements can open up a whole new level of appreciation. Consider this your cheat sheet for getting the most out of the experience, especially if you’re fortunate enough to see a show.

Kumadori: A Whole Vibe

First is the makeup, or kumadori. This isn’t just about looking striking; it’s a color-coded system that reveals everything you need to know about a character’s nature. The patterns are bold, dramatic, and loaded with meaning. A series of vivid red lines on a white base? That’s your hero—brave, strong, and virtuous. Deep blue or black lines? You’re looking at a villain—a demon, ghost, or a genuinely bad character. Brown lines often represent spirits or monsters beyond human. Each line and color is symbolic, transforming the actor’s face into a living mask that conveys their inner essence. It’s a visual language that’s both stunning and incredibly efficient storytelling.

Onnagata: Performance on Another Level

One of kabuki’s most intriguing features is the tradition of the onnagata. These are male actors who specialize in female roles. This custom dates back to the early Edo period when women were banned from the stage. But this isn’t just a man dressing as a woman. The onnagata is a highly refined, stylized art form. These actors devote their entire lives to capturing the essence of femininity—not by simply imitating women, but by creating an idealized, theatrical version of womanhood through their gestures, voice, and movements. The skill, grace, and subtlety they attain is truly breathtaking. It’s a cornerstone of kabuki’s distinctive aesthetic.

Mie: Strike the Perfect Pose

At the height of a scene or during a deeply emotional moment, an actor may suddenly freeze in a dramatic, expressive pose, often crossing one eye. This is called a mie. It’s like a cinematic freeze-frame, meant to capture the peak of emotion and imprint the image on the audience’s mind. It’s a moment of pure, concentrated energy. As the actor holds the mie, you might hear the sharp clap of wooden blocks offstage, ramping up the tension. It’s one of kabuki’s most iconic and electrifying techniques—a powerful gesture signaling a moment of ultimate significance.

Kakegoe: The Audience’s Cheer Squad

Don’t be surprised if, during the performance, you hear audience members shouting what sound like names or random words at key moments, especially after a rousing speech or a flawless mie. These are kakegoe, an important part of the interactive kabuki experience. They’re not random heckles; they’re cheers of appreciation, usually aimed at a particular actor. The callers are often seasoned fans who know exactly when to participate. They might shout the actor’s yago (guild name) or other words of encouragement. Far from being a distraction, kakegoe show that the audience is knowledgeable and engaged, boosting both the actor and the crowd. It’s a living tradition that creates a unique connection between stage and audience in a distinctively Japanese way.

The How-To: Your Game Plan for Visiting Kanamaru-za

Alright, you’re convinced. You’re ready to experience this historic treasure yourself. Here’s the essential information you need to make it happen, whether you’re joining a tour or trying to secure tickets for a major performance.

Getting There: The Route to Kotohira

Kotohira is a quaint town situated in Kagawa Prefecture on Shikoku, Japan’s smallest of the four main islands. The easiest way to reach it is by train. From major cities like Osaka or Kyoto, take the Shinkansen (bullet train) to Okayama. From there, transfer to the JR Seto-Ohashi Line, which crosses the stunning Great Seto Bridge and leads to Kotohira. The ride offers spectacular views of the Seto Inland Sea. If you’re already on Shikoku, for instance in Takamatsu, the prefectural capital, it’s a short and straightforward trip via local JR or Kotoden trains. Once you arrive at either JR Kotohira Station or Kotoden-Kotohira Station, the theater is a 15-20 minute walk along the town’s main street, heading up to the Konpira-san shrine entrance.

Tours vs. Performances: Two Ways to Enjoy the Experience

Most of the year, Kanamaru-za functions as a museum you can tour. It’s unquestionably one of the finest historic site tours in Japan. You have great freedom to explore—walk on the main stage, cross the hanamichi, sit in the masu-seki, and most importantly, go backstage and under the stage to see the mawari-butai and seri mechanisms up close. This hands-on experience offers a unique understanding of how the theater operates. Volunteer guides usually provide explanations in basic English or Japanese, and there are plenty of informative signs. The theater is generally open from 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM, but be sure to check the official website for current hours and any closures.

The ultimate experience is attending a live kabuki performance during the Shikoku Konpira Kabuki Oshibai held in April. This event is a completely different experience—the theater bursts with energy. Tickets are highly sought after and can be hard to get. They typically go on sale a few months in advance and can be bought online via official ticketing platforms like Ticket Web Shochiku or through convenience store kiosks in Japan. If you plan to attend, be prepared to book as soon as tickets are released. Even without understanding Japanese, the visual spectacle of the costumes, makeup, and stagecraft makes it well worth it.

Pro Tips for Your Visit

- Easy-to-Remove Shoes: Like many traditional Japanese venues, you’ll need to take off your shoes upon entering. Choose footwear that’s simple to slip on and off.

- Cash is Preferred: Although Japan is becoming more card-friendly, many small towns and cultural sites still operate mainly on cash. Bring enough yen for your ticket and souvenirs.

- Photography Guidelines: Photography is usually permitted during standard tours but strictly forbidden during live performances. Always follow the rules.

- Don’t Miss the Understage: Be sure to explore the naraku (understage area). It’s often the most fascinating part for visitors and offers great insight into the theater’s mechanics.

Beyond the Theater: Vibing in Kotohira

Your visit to Kanamaru-za also offers a chance to explore the deeply spiritual and picturesque town of Kotohira. The theater is not isolated; its history is intricately linked to the fabric of this renowned pilgrimage town.

The Climb: Kotohira-gu Shrine (Konpira-san)

The main attraction in town, besides the theater, is the climb to Kotohira-gu Shrine. Be ready for some exercise, as reaching the main hall requires ascending 785 stone steps. The route is lined with souvenir shops, eateries, and stone lanterns, turning the climb into a memorable experience. If you prefer, you can even hire a palanquin to carry you part of the way. The view from the summit, overlooking the Sanuki Plain, is truly rewarding. The shrine complex itself is tranquil and beautiful. For the truly committed, an additional 583 steps lead to the inner shrine (Okusha), a more peaceful and mystical spot. The shrine’s history and the pilgrims who visited it are the very reason Kanamaru-za came into being.

Fuel Up: The Glory of Sanuki Udon

Kagawa Prefecture is renowned across Japan for one thing above all: udon. Specifically, Sanuki Udon, prized for its firm and chewy texture. You simply can’t leave Kotohira without savoring a bowl. Numerous udon shops throughout the town each offer their unique take on this local specialty. Whether served hot in a simple broth (kake udon) or cold with dipping sauce (zaru udon), it’s the perfect, tasty, and affordable meal to recharge after your climb.

Stroll the Town

Take some time to leisurely browse the streets of Kotohira. Along the main approach to the shrine, you’ll find shops selling local crafts and snacks. Don’t miss the Takatoro, a towering 27-meter stone lantern that once served as a functioning lighthouse, guiding vessels on the Seto Inland Sea. The town is also home to several sake breweries where you can sample local brews. The entire area exudes a charming retro Showa-era vibe, especially in the evening when lanterns glow and the streets quiet down.

A Final Bow

A trip to Kanamaru-za is more than merely checking off a historical site from your list. It’s an emotional journey into the past. The venue engages all your senses and connects you to the raw, creative spirit of Japan’s history. Standing on that stage, you’re not simply a visitor; you’re part of a story that has been unfolding for nearly two centuries. You can sense the dedication of the craftsmen who built it, the passion of the actors who performed there, and the joy of the audiences who brought it to life. Kanamaru-za serves as a reminder that the most remarkable special effects often come from human creativity and that a simple wooden structure can hold more magic than any modern stadium. It’s a place that is authentically, unapologetically itself—a true icon. No doubt, this place is legendary, and the memories you create here will stay with you forever. It’s a must-visit for anyone seeking to experience the genuine, vibrant heart of Japanese culture.