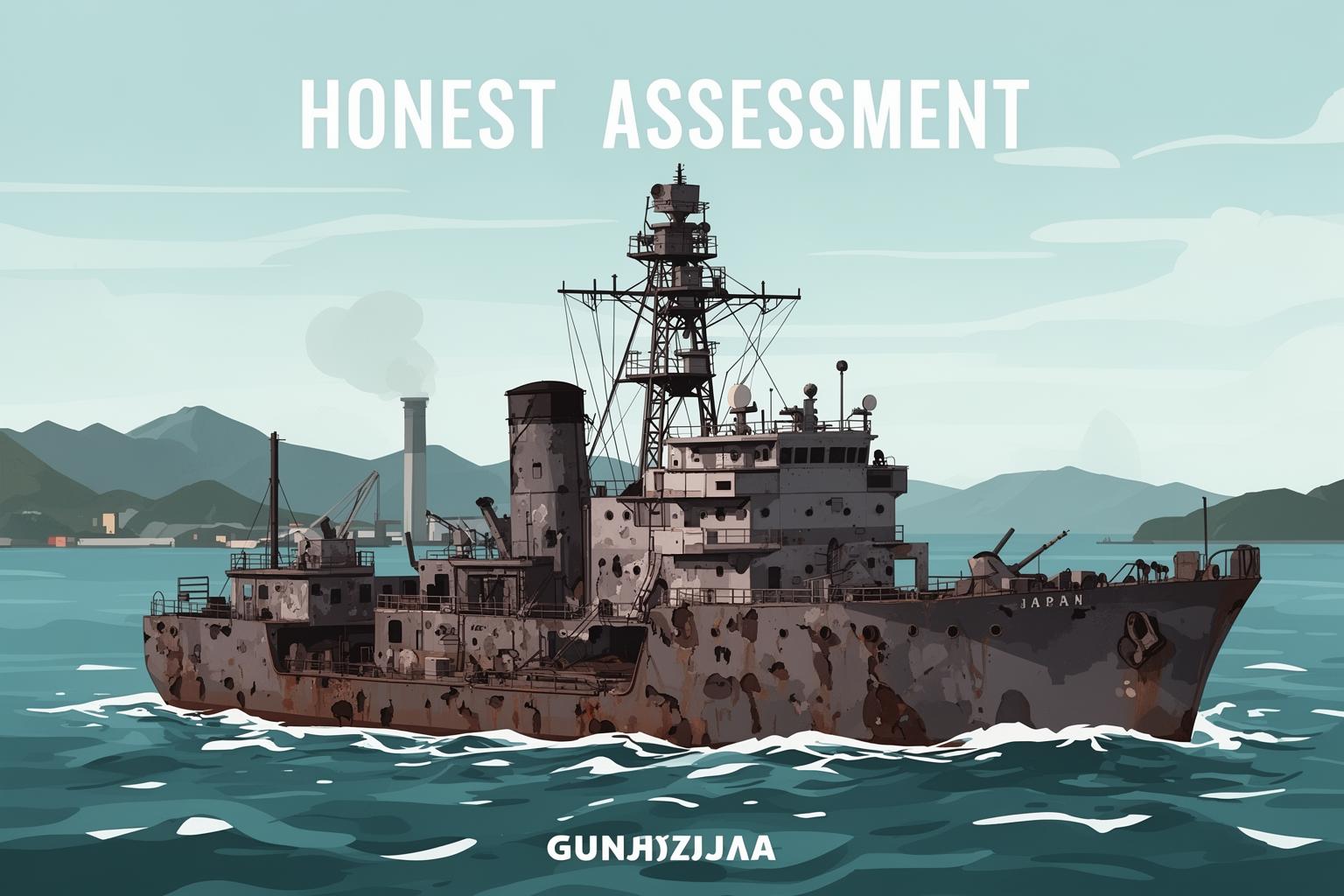

Yo, what’s up. Keiko here. Let’s talk about something you’ve probably seen scrolling through your feed—a concrete ghost island floating off the coast of Japan, looking like a level straight out of a video game. It’s Gunkanjima, or “Battleship Island,” and honestly, the pics don’t even do it justice. They show the decay, the insane density, the whole post-apocalyptic vibe. But what they don’t capture is the why. Why are we, as a culture, so drawn to this place? You see it in anime, in movies, as this ultimate aesthetic of beautiful destruction. It’s this weird mix of being totally unsettling but also, low-key, beautiful. It’s a question that gets at the heart of something uniquely Japanese, this fascination with things that are broken, transient, and forgotten. You come to Japan expecting neon-drenched cities and serene temples, and you get those, for sure. But then you find out one of the most sought-after tourist experiences is a boat trip to a crumbling industrial island that was abandoned half a century ago. It’s a mismatch, right? It feels like there’s a piece of the cultural puzzle missing. So, let’s get into it. Why does this concrete carcass of an island hit different? Why is this silent, decaying metropolis a mirror to the modern Japanese soul? It’s not just about “dark tourism.” It’s deeper than that. It’s about our relationship with history, with nature, and with the idea that nothing, not even a city built to last forever, actually does. It’s a whole mood, a tangible piece of a philosophy we live and breathe. Before we dive deep, let’s get our bearings and see exactly where this legendary island is at.

To truly understand this fascination, it’s essential to learn about the silent etiquette followed by Japan’s haikyo explorers.

The IRL Post-Apocalypse: What Even IS Gunkanjima?

First, let’s get the basics down. Gunkanjima’s official name is Hashima, though hardly anyone calls it that. The nickname stuck because from afar, its silhouette—dotted with massive concrete apartment blocks and industrial facilities—resembles a Tosa-class Japanese battleship. It’s a tiny island, about 16 kilometers off the coast of Nagasaki. Seriously small, like you could walk across it in just a few minutes. But in its heyday, it was the most densely populated place on Earth. Ever. For real. Think about that. At its peak in the late 1950s, more than 5,000 people were packed onto this rock. That’s a population density that makes modern Tokyo or Shibuya Crossing look spacious. It’s wild.

So, what was everyone doing there? Coal. The island sits above a large undersea coal mine. Mitsubishi bought the island in 1890 and went all-in, turning it into a self-contained city. They built Japan’s first large-scale reinforced concrete apartment building here in 1916. This place was the future, a symbol of Japan’s frantic rush to industrialize and modernize during the Meiji era. It was a vertical city before vertical cities became a global trend. Everything was connected by a maze of corridors and stairways, shielding residents from the typhoons that battered the island. It had schools, a hospital, a cinema, shops, a pachinko parlor, a shrine—literally everything needed for modern life, all enclosed within a concrete sea wall. It was a microcosm of Japan’s ambitions: conquer nature, build efficiently, and fuel the nation’s growth.

Then, in 1974, it all came to a halt. Petroleum replaced coal as the main energy source, the mine shut down, and Mitsubishi offered everyone jobs on the mainland. Within months, the entire population disappeared. They packed what they could carry and left the rest behind. The city was switched off, abandoned to the wind and salt spray. And that’s what makes it so captivating today. It’s not a ruin from an ancient civilization; it’s a modern metropolis, frozen in the mid-70s. It’s a snapshot of a life that abruptly ended. When you see it, the scale hits you first. The concrete buildings look like giant, hollowed-out skeletons. They’re all shades of gray and brown, streaked with rust and water stains. Windows are smashed, like vacant eyes. Greenery is starting to reclaim its space, with vines creeping up walls and grass growing through pavement cracks. It’s an unfiltered vision of what happens when humanity vanishes and nature begins to take over. The atmosphere is heavy. It’s not just empty; it’s silent in a way modern cities never are. You can almost hear the absence of people, the ghost of a once-bustling community. That feeling is at the heart of its appeal and what fascinates filmmakers and game designers so much. It’s not fantasy; it’s a real place that perfectly embodies the post-apocalyptic trope.

The Island’s Origin Story: A Concrete Utopia or a Capitalist Fever Dream?

To truly grasp Gunkanjima, you must understand the dream that brought it to life. This was far from a rough-and-ready mining camp; for a time, it was promoted as a genuine utopia. It was a vision of the future, born from Japan’s urgent need for energy to power its industrial revolution. The late 19th and early 20th centuries marked a period of intense transformation for Japan, which was striving to catch up with the West, with coal serving as the fuel for that ambition. Mitsubishi, one of the massive zaibatsu (family-owned business conglomerates) that essentially built modern Japan, recognized the value of the undersea coal seams beneath Hashima, investing enormous resources and engineering expertise into the project.

The goal was to create a perfect, highly efficient community for miners and their families. With no space left on the island, the only option was to build upwards. This gave rise to the iconic concrete high-rises that define the island’s skyline. These structures were more than mere buildings; they were a symbol—a commitment to modernity and technology over tradition. While the famous Western-style Glover House in Nagasaki is often cited as a symbol of the era, Gunkanjima’s Building 30 was arguably even more revolutionary—a nine-story concrete apartment block for those fueling the nation. This industrial fortress was designed to be fully self-sufficient, even experimenting with rooftop vegetable gardens, adding patches of green to the concrete landscape. It was an ambitious experiment in social engineering and urban planning.

Life in the Concrete Jungle: Highs and Lows

Life on Gunkanjima was a story of extremes. On one hand, residents enjoyed a standard of living that was advanced for its time in mainland Japan. By the post-war period, the island boasted some of the highest rates of television ownership in the country. A strong sense of community prevailed, one that former inhabitants recall with deep nostalgia. Everyone knew one another, doors were often left unlocked, and children played safely in the maze-like corridors, shielded from traffic. The company provided housing, healthcare, and education. From the outside, it appeared as a model society—an ideal little kingdom built on coal.

Yet, beneath this futuristic vision lay brutally dangerous labor. Mining was grueling and perilous. Miners descended in cramped cages over 600 meters below sea level into hot, humid tunnels constantly threatened by collapse or flooding. Temperatures could reach 30 degrees Celsius with 95% humidity. Gas explosions were an ever-present danger. This harsh, life-threatening work powered the bright lights of the utopia above. This contrast is vital to understanding the island’s essence. Gunkanjima was a place of great pride and progress, yet also immense hardship and sacrifice. It perfectly embodies the Japanese concept of gaman—enduring the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity. The miners and their families were not merely living on an island; they were living with intense, focused purpose—all centered around the singular mission of extracting coal beneath the sea.

The Good Life? Schools, Cinemas, and Sky-High Dreams

Focusing on the “utopia” aspect, it was indeed very real for many residents at one time. The company’s investment in community infrastructure was exceptional. The school, located at the island’s center, was a massive seven-story building featuring a gymnasium and a rooftop playground—the only available open space. Imagine playing tag or holding a sports day on a rooftop concrete playground surrounded by ocean. It’s a uniquely Gunkanjima image. The island housed a state-of-the-art hospital, complete with an operating room and X-ray equipment. There was a movie theater showing the latest films, adding a touch of glamour and escapism. Other amenities included public baths, a festival shrine, bars, and even a brothel. For families living there in the 1950s and ’60s, it felt like being at the forefront of Japanese prosperity. They were part of a vital national effort and had access to facilities still rare in many rural areas. This era forged a powerful bond among islanders, who formed a close-knit community united by their unique circumstances and shared purpose. This intense community spirit is a major part of Gunkanjima’s legend and contributes to the profound feeling of loss surrounding the island’s ruins today.

The Dark Side: The Reality of Undersea Mining

However, the dream was fueled by a nightmare. The work was unimaginably harsh. Miners labored in shifts around the clock, carving coal from narrow, dark tunnels deep beneath the ocean floor. The physical demands were extreme, and beyond the danger of accidents, the long-term health impact of inhaling coal dust was devastating. The story turns darker still during World War II, when, like many Japanese industrial sites, Gunkanjima relied on forced labor. Hundreds of Korean and Chinese civilians and prisoners of war were forced to work under horrific conditions, many dying from malnutrition, exhaustion, and accidents. This painful chapter is a crucial, often overlooked part of Gunkanjima’s history. It complicates the nostalgic narrative of a close-knit community and modern utopia. This tragic legacy remains a matter Japan continues to confront, adding a deep layer of sorrow to the island’s silence. The ghosts of Gunkanjima are not just the happy families who left in 1974, but also the souls of those coerced to toil and perish there. This dual nature is essential to understanding the island—it stands as both a pinnacle of Japan’s industrial achievement and a symbol of its wartime cruelty. One cannot truly comprehend Gunkanjima without acknowledging both sides.

The Big Quiet: Why Did Everyone Just… Leave?

The end came unexpectedly quickly. It wasn’t a slow decline or a gradual departure. It was an immediate full-stop, lights-out, everybody-leaves situation. The trigger was straightforward: the energy crisis of the 1970s. The world was transitioning from coal to petroleum. For Japan, a nation with virtually no domestic oil reserves, this represented a major economic shift. Coal mines throughout the country, once the drivers of the post-war economic miracle, suddenly became obsolete. Gunkanjima’s undersea mine was especially costly to operate, and as coal demand sharply dropped, it ceased to be financially viable.

In January 1974, Mitsubishi officially declared the mine’s closure. The announcement shocked the island community. Their entire world—the only life many had ever known—was being dismantled. In line with the lifetime employment system of the time, the company offered to relocate all workers to other Mitsubishi plants on the mainland. This provided a lifeline but also meant abandoning everything behind. The evacuation proceeded swiftly and smoothly. Over the next three months, from January to April, the island was emptied. Families packed their personal belongings—clothes, photographs, important papers—and boarded ferries to Nagasaki, leaving their homes forever. They left behind furniture, televisions, kitchenware, toys. They left classrooms filled with desks and chairs, the clinic stocked with medical instruments. There was no time, and often no room in their new lives, for these bulkier possessions. They locked the doors of their apartments and simply walked away, unaware they would never be opened again by human hands.

Picture the feeling on that final day, April 20, 1974. The last residents boarding the ferry, watching their concrete city grow smaller on the horizon. The vibrant sounds of 5,000 people—children playing, miners heading to work, market chatter—replaced by nothing but wind and waves. This sudden, sharp shift from a bustling, densely populated city to a total ghost town is what makes Gunkanjima’s story so powerful. It wasn’t destroyed by war or disaster. It became obsolete through economic change. It died quietly, clinically. The very force that built it—Japan’s relentless modernization—also sealed its fate. The island stands as a testament to the harsh efficiency of that cycle. When something loses its usefulness in Japan, it is often completely discarded. This lack of sentimentality in progress can be startling to outsiders. Gunkanjima is the ultimate example: a city that turned from the future into a relic in the blink of an eye. The “Big Quiet” that enveloped it is a deep, unsettling silence—the sound of an era ending overnight.

Frozen in Time: Reading the Ghost Stories in the Walls

Visiting Gunkanjima, whether through the limited tourist path or the thousands of photos available online, feels like stepping into a time capsule. The true power of the place lies not just in the vast scale of the crumbling buildings but in the intimate, personal details left behind. These fragments tell the human story. The city wasn’t cleaned up before abandonment; it was simply deserted. This gives it a feeling more akin to the aftermath of a sudden, mysterious event—like the Rapture—rather than a typical historical ruin. It’s an archaeologist’s dream and a ghost hunter’s paradise. The stories are literally etched on the walls, scattered across the floors, and lingering in the air.

The salt-laden atmosphere has been both destructive and preservative. It has corroded metal, shattered windows, and caused concrete to crumble, but it has also, paradoxically, sealed everything into a dusty, decaying stasis. Walking through images of these interiors is an intensely voyeuristic experience. You peer into the lives of people who left in a hurry, their presence still palpable. You might spot a vintage 70s television in the corner of a living room, its screen dark and dusty. Nearby on a table might sit a rotary phone, waiting for a call that will never come. In a kitchen, rice bowls and chopsticks might still rest in a drying rack. These everyday objects become deeply poignant relics—silent witnesses to the moment life froze.

Apartment 65: A Glimpse into Everyday Life

One of the island’s most famous and photographed locations is Building 65, a larger and later apartment block. Exposed to the full force of typhoons, it has decayed dramatically. Some floors have had their outer walls ripped away, creating a real-life cutaway dollhouse effect. You can see directly into the apartments, each a miniature stage set of a life abruptly interrupted. In one unit, tatami mats rot on the floor, a low table lies overturned, and wallpaper peels off in long strips. In another, a child’s toy rests on the ground, a splash of faded color in a gray world. These are not just empty rooms; they are spaces imbued with the powerful aura of domesticity. You can almost trace the family’s daily routine, imagining where they slept, ate, or gathered to watch TV after a long day. The decay tells its own story—the wind scattering papers across a room, a curtain billowing from a broken window frame—all part of the island’s new, post-human narrative. It serves as a strong reminder that our homes, the places we fill with life and identity, are only temporary shelters against the relentless forces of time and nature.

The Silence of the Schoolhouse

For many, the school building is the most haunting spot on Gunkanjima. Schools are meant to be filled with noise, energy, and life. To see one in a state of complete silence and decay is profoundly unsettling. Inside, classrooms contain rows of wooden desks and chairs thickly coated with dust and debris. The blackboard might still bear faint chalk marks, ghosts of a final lesson. In the music room, a piano’s exposed keys have warped under decades of humidity. Textbooks and notebooks lie scattered on the floor, their pages swollen and browned with age. Here, the sense of lost potential is most acute. One thinks of the thousands of children who grew up on this concrete island—whose laughter and shouts once echoed through these halls—now replaced only by the sound of wind whistling through broken glass. The space is charged with memory, its emptiness a profound statement on the fragility of community and the unstoppable passage of time. The school stands as the heart of the island’s ghost story, where the past feels so present you can almost reach out and touch it.

Echoes in the Doctor’s Office

Another deeply evocative location is the island’s hospital and clinic. Exploring images of this place feels like a scene from a horror movie, yet it is real. Examination rooms reveal rusted equipment. An old-fashioned wheelchair might be parked in a hallway. Bottles of medicine with faded labels still rest on shelves. The operating theater, with its imposing overhead lamp and tiled walls, is particularly chilling. These spaces were charged with the drama of life and death—places of healing and hope, but also of suffering and loss, especially given the hazardous nature of mining work. Now, in a state of advanced decay, the clinic is a visceral experience. Peeling paint, grime-covered instruments, and disorder speak of a sudden halt to care. This stark visual metaphor embodies the island itself: once a vital organ of Japan’s industrial body, surgically removed and left to atrophy. The clinic’s decay highlights human vulnerability and the systems we build to protect ourselves, showing how quickly sterile, controlled environments can be overtaken by natural forces once abandoned.

The “Why” We’re Here: Gunkanjima and the Japanese Soul

So, here’s the deal: the place has an undeniable vibe. It’s a photographer’s paradise and a movie scout’s goldmine. But what gives it that deep, cultural significance? Why is it more than just “ruin porn” to us? The answer lies in core Japanese aesthetics and philosophies that outsiders often struggle to fully understand. Gunkanjima embodies the concept of mono no aware in its physical form. This essential Japanese idea defies a simple English translation, but it can be thought of as “the pathos of things,” or “a gentle sadness for the fleeting nature of existence.”

It’s the feeling you get in spring when you see cherry blossoms—beautiful, yes, but their fleeting lifespan adds a bittersweet layer to that beauty. It’s an acceptance that everything is transient. Gunkanjima is mono no aware cast in concrete and steel. Once a vibrant, thriving city at the height of modernity, it now stands as a decaying relic slowly reclaimed by nature. Witnessing it stirs the same emotion: sorrow for what’s lost, but also a profound appreciation for the beauty found in decay. It’s a striking memento mori, a reminder of life’s inevitable cycles of birth, death, and renewal. This perspective isn’t purely sorrowful; it’s a fundamental truth to which peace and beauty can be found in acceptance. Gunkanjima confronts us with this truth on a grand, awe-inspiring scale.

It’s Giving… Wabi-Sabi: The Beauty in Imperfection

Alongside mono no aware is the concept of wabi-sabi, a term you might be familiar with. Though often simplified as “rustic beauty,” it’s far more intricate. Wabi-sabi finds beauty in imperfection, impermanence, and incompleteness. It embraces asymmetry, roughness, simplicity, and the marks of age and weathering. Think of a handcrafted tea bowl with slight irregularities or a piece of timeworn wood. Gunkanjima is wabi-sabi magnified on a monumental scale. The crumbling concrete, rust streaks resembling tears, and nature’s reclamation of man-made structures—all embody perfect imperfection. This contrasts sharply with the polished, flawless aesthetic also prominent in Japan. It celebrates the beauty of reality over ideals. No architect designed the patterns of decay on Building 65’s walls; time and typhoons crafted them. The result is something more organic, poignant, and perhaps even more beautiful than the original sterile concrete. This reverence for imperfection and decay is central to Japanese aesthetic sensibilities, and Gunkanjima stands as its grand cathedral.

Haikyo Culture: Why We Connect with Ruins

Gunkanjima also reigns supreme in a Japanese subculture known as haikyo, meaning “ruins,” which involves exploring and photographing abandoned places. This is a huge community, with enthusiasts hunting abandoned schools, hospitals, amusement parks, and industrial sites. What draws people in? Certainly the thrill of discovery and trespassing, but just as deeply, it ties into mono no aware and wabi-sabi. Haikyo explorers are like modern monks, seeking spaces to meditate on impermanence. These ruins offer quiet, pressure-free environments away from the noise of modern Japanese life, places for reflection. Before opening to tourists, Gunkanjima was the ultimate haikyo pilgrimage, a legendary forbidden kingdom of decay. Today’s formal tours have made it more accessible, but the core allure remains unchanged: connecting with a recent past that feels both strange and familiar. It’s about witnessing the future our grandparents built and seeing its current fate. For younger Japanese generations raised during economic stagnation, these ruins of the high-growth era hold a particular fascination—relics of a mythical time of hope and progress whose decay mirrors the nation’s shifting fortunes.

A Reflection of Modern Japan: The Cycle of Build, Destroy, Repeat

On a broader level, Gunkanjima stands as a perfect metaphor for Japan’s modern history. Our nation is locked in a continuous cycle of dramatic destruction and relentless reconstruction. We’ve long endured natural disasters like earthquakes, tsunamis, and typhoons that can obliterate entire communities in moments. Then came World War II’s devastation, which reduced major cities to ashes. Yet, after every catastrophe, we rebuild—bigger, stronger, and more advanced. Tokyo exemplifies this, with few ancient buildings surviving its repeated leveling and rebuilding. This “scrap and build” mentality is ingrained in our national psyche. Unlike many Western cultures, we lack a strong attachment to preserving old buildings. We accept that things have lifespans and when their time ends, they should be replaced by something new and improved. Gunkanjima is a rare exception. Though it was abandoned, it was never rebuilt. It remains in suspended decay—an unusual case of allowing a place simply to die. This makes it uniquely powerful for reflection, forcing us to face the consequences of our unending drive for progress. It prompts the question: What do we lose when we relentlessly chase the future and quickly discard the past? The island stands as a monument not only to a single industry but to an entire era of Japanese identity, its silence provoking a national self-examination that is at once uncomfortable and essential.

The Controversy: More Than Just a Pretty Ruin

Alright, we’ve discussed the aesthetics, philosophy, and overall vibe. But we need to confront the darker aspects of Gunkanjima’s history, as they are central to ongoing controversies and complicate the narrative. In 2015, Gunkanjima was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site as part of a group of locations tied to Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution. This was a significant recognition of the island’s role in Japan’s rapid modernization. However, the decision has been, and remains, highly contentious, especially for South Korea and China.

Why is that? Because Japan’s official narrative largely emphasized the Meiji-era achievements—technological innovation and the creation of a modern industrial state—while largely overlooking the period from the 1930s to 1945, when the island was the site of brutal forced labor, as we have discussed. The UNESCO application celebrated Japan’s industrial prowess, but for the descendants of forced laborers, the island symbolizes suffering and exploitation. During the UNESCO review process, Japan committed to measures that would “allow an understanding that many Koreans and others were brought against their will and forced to work under harsh conditions.” This commitment was a condition for the bid’s approval.

Nonetheless, the fulfillment of this promise has faced severe criticism. The official information center for the site, located in Nagasaki, has been accused of minimizing or ignoring the forced labor issue, choosing instead to highlight the nostalgic, idealized narrative of the island’s heyday. Testimonies from former residents featured at the center often depict a happy, harmonious community, which contradicts the testimonies of forced labor survivors. This has led to charges of historical revisionism from South Korea and a formal warning from the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, which has persistently urged Japan to fully and accurately present the complete history of the site. It remains a complex, ongoing political and historical conflict. For visitors, understanding this context is crucial. The island is not simply a neutral, aesthetically pleasing ruin. It is a contested place where different and often painful historical narratives converge. Appreciating the wabi-sabi of the decaying concrete without recognizing the human suffering that occurred there shows only part of the story. It serves as a powerful reminder that history is never straightforward, and the stories we choose to tell—or omit—about our past carry profound significance.

Is the Trip Worth the Hype? Real Talk

So, after all that—the history, the philosophy, the controversy—the key question remains: Is visiting Gunkanjima truly worth it? It’s neither the easiest nor the most affordable trip. You must reserve a spot on a licensed tour boat from Nagasaki, the journey occupies a significant part of your day, and there’s no certainty you’ll be allowed to land. If the seas are too rough, the boats will simply circle the island before returning. So, is the real-life experience worth the effort and the cost?

Here’s the straight talk. Manage your expectations. The photos you’ve seen online, taken by haikyo explorers who once sneaked onto the island illegally, depict a level of access you won’t have. You can’t just roam the abandoned apartments or explore the schoolhouse. For safety reasons, tours are confined to a specially built walkway covering only a small section of the island. You’ll see the main apartment blocks and industrial areas from a distance, but no urban exploration will be allowed. It’s a highly controlled, curated experience. You’ll be in a large group, listening to a guide (usually in Japanese, though some tours offer audio guides), and will only spend about an hour on the island.

Does this spoil the experience? Not necessarily, but you must know what to expect. Seeing the island with your own eyes has undeniable impact. The massive concrete structures, the feel of the sea breeze, the sound of waves crashing against the seawall—it’s an immersive sensory experience that photos can’t fully convey. The boat ride itself adds to the story; as the island gradually appears on the horizon, resembling its battleship namesake, it’s a breathtaking moment. You gain a profound sense of its isolation and fortress-like character.

My advice? Go for it, but with the right mindset. Don’t expect a solitary, meditative haikyo adventure. Go as an observer. You’re there to witness a unique and powerful monument to a specific chapter of human history. Listen to the guide, absorb the atmosphere, and try to imagine the lives once lived within those crumbling walls. The most memorable part of the visit isn’t about capturing the perfect Instagram shot; it’s about standing before this silent giant and feeling the weight of its story. It will prompt reflections on progress, community, and the astonishing speed of change in our world. It’s not just a tourist destination; it’s a philosophical experience. For anyone seeking to understand the complex, contradictory spirit of modern Japan—our ambition, our cruelty, our fascination with impermanence, and our endless cycles of creation and destruction—there is no better classroom than this ghost ship drifting on the East China Sea. It’s a curriculum in concrete, and truly, a lesson you won’t forget.