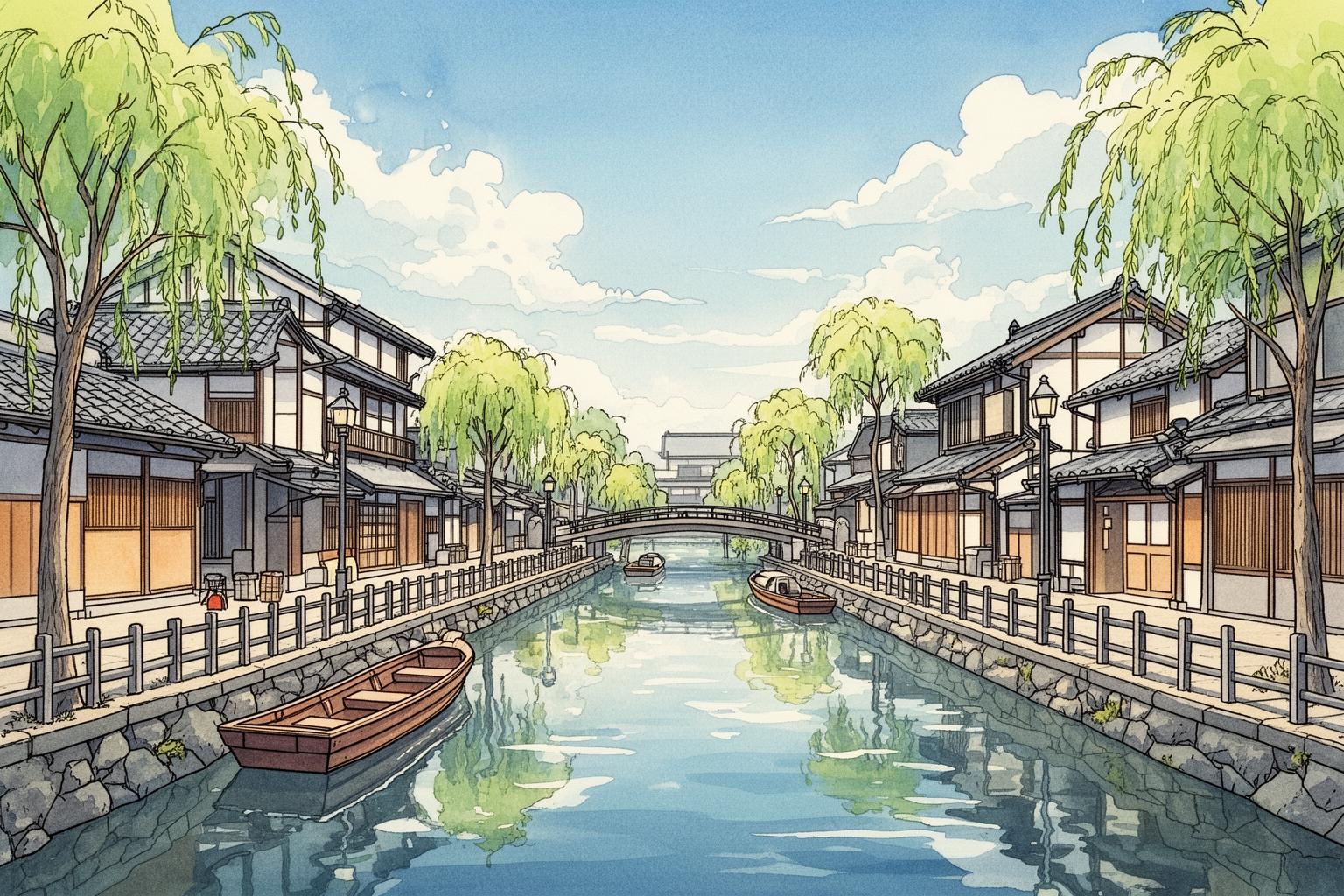

Yo, what’s up, fellow history buffs and travel addicts? Let’s get real for a sec. When you think of Japan, you probably picture the neon glow of Tokyo, the serene temples of Kyoto, or maybe the epic powder of Hokkaido. All legit. But what if I told you there’s a place that flips the script, a spot where time slows down to the gentle pace of a punt drifting through a maze of ancient canals? We’re talking about Yanagawa, a city in Fukuoka Prefecture that’s been vibing with its own flow for centuries. Forget the bullet train hustle; this is the slow lane, the ultimate analogue experience in a digital world. Dubbed the ‘Venice of Japan,’ Yanagawa isn’t just a cute nickname; it’s a living, breathing water world, a city built not just near water, but by it and for it. The main event here is the ‘kawakudari,’ or punting down the river, a 70-minute float trip that’s less of a tourist ride and more of a time-traveling meditation. You’re not just seeing the sights; you’re drifting through the very arteries of a 400-year-old castle town, guided by a boatman who’s part skipper, part historian, and part folk singer. It’s a full-sensory deep dive into a side of Japan that’s soulful, poetic, and utterly captivating. This isn’t just about pretty pictures for the ‘gram; it’s about connecting with a rhythm of life that’s been preserved for generations. It’s the real deal, a historical masterpiece you can literally float through. So buckle up, because we’re about to explore the heart and soul of this epic water city.

After your serene boat ride, you’ll definitely want to explore the energetic Fukuoka yatai street food scene for a perfect contrast.

The Historical Tea: How a Castle Town Got Its Flow

Alright, let’s spin the historical record, because you can’t truly capture the Yanagawa vibe without knowing its backstory. This place didn’t just appear as a tourist-friendly water park. No, its very existence is a saga of power, engineering, and resilience, all revolving around the legendary Tachibana clan. The story is classic feudal Japan drama—and it’s epic. Back in the late 16th century, during the Sengoku period—the ‘Warring States’ era, essentially the heavyweight championship of samurai warlords—a man named Tachibana Muneshige arrived. He was a bona fide legend, a warrior so respected that even his enemies recognized his prowess. He established Yanagawa as his castle town, but here’s the clever part: the area was a flat, marshy plain. Not exactly ideal for a fortress. So what did they do? They embraced it. They didn’t fight the water; they turned it into an asset.

The intricate canal network, called ‘horiwari,’ that you see today wasn’t originally for leisurely boat rides. It was a cutting-edge defense system. These waterways acted as moats, a vast, interconnected barrier designed to stop any invading force. Imagine trying to lead a cavalry charge through a maze of water—impossible. The canals controlled access, created choke points, and turned Yanagawa Castle into a tough nut to crack. But their purpose went beyond military defense. This was a masterpiece of civil engineering. The horiwari system also served as a massive irrigation network, directing water to nearby rice paddies and transforming marshland into fertile farmland. It was a critical transportation grid for moving goods, supplies, and people throughout the domain. Most importantly, it was a brilliant flood control system, managing heavy rainfall and protecting the town from flooding. The entire community revolved around the canals. Life moved with the water. Samurai residences had private docks; merchants transported goods on barges. It was the city’s lifeblood, where defense, agriculture, and daily life merged seamlessly.

But history, as always, threw a curveball. After the decisive Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, Muneshige, having sided with the losing faction, was stripped of his domain. It was a huge blow. But here’s where the story gets even better. Muneshige was so respected that he eventually fought back, and in 1620, he was reinstated as lord of Yanagawa. The crowd goes wild! This comeback solidified the Tachibana clan’s legacy, and they ruled Yanagawa throughout the Edo period. For over 250 years, they maintained and refined the canal system, shaping the city as we know it today. After the samurai era ended with the Meiji Restoration, the canals could have fallen into neglect. Their military use was outdated. But the people of Yanagawa recognized their importance. They dredged, maintained, and repurposed them. The transformation from functional fortress moats to tranquil waterways for sightseeing boats—the ‘donko-bune’—showcases the town’s ability to evolve while preserving its identity. Drifting down these canals today, you’re literally floating through layers of history—a defense strategy, an agricultural lifeline, and now, a symbol of timeless beauty.

The Main Event: Catching a Vibe on a Donko-bune

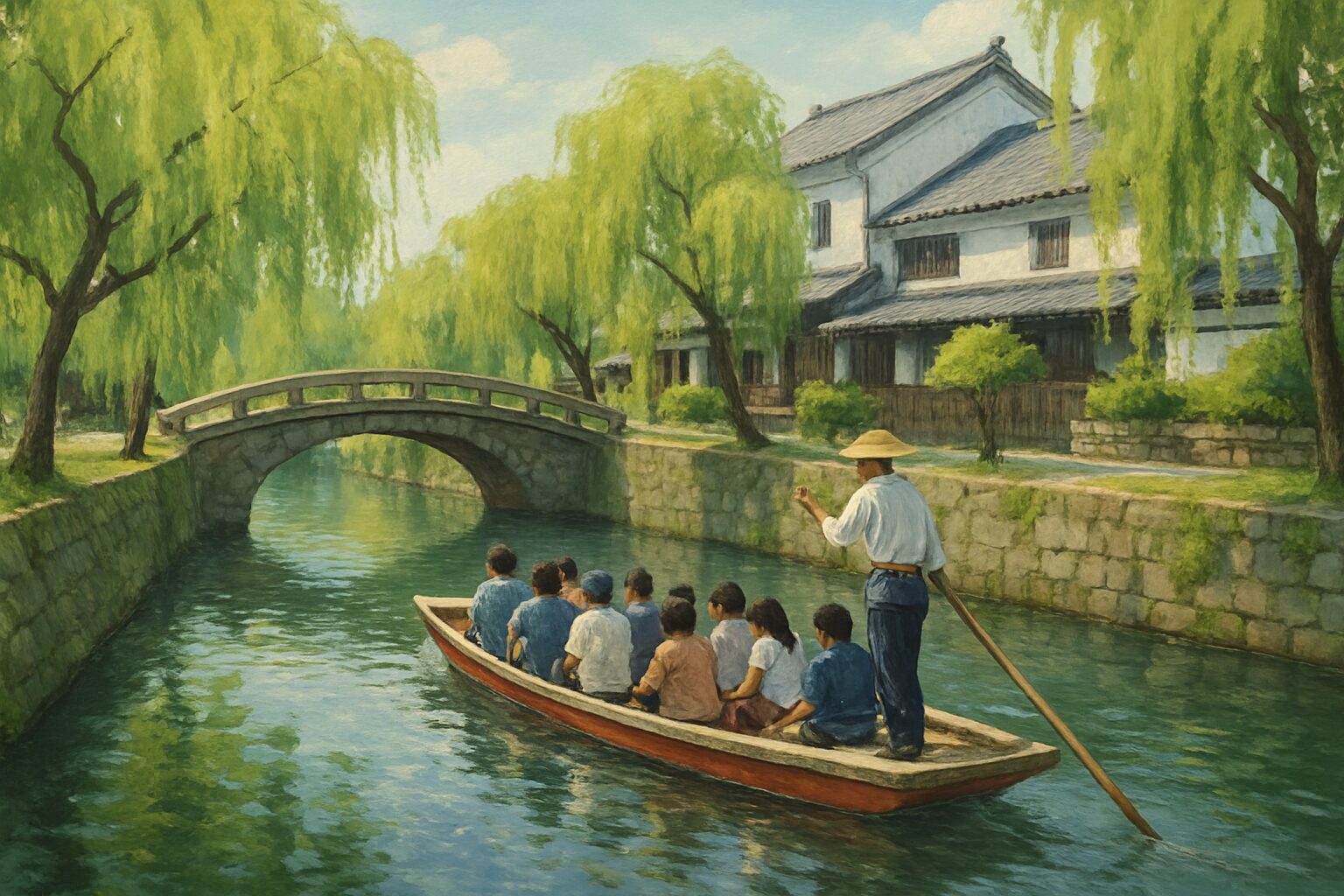

So, you’re in Yanagawa, familiar with its historical background, and now it’s time to dive into the experience itself. The kawakudari on a ‘donko-bune’ is absolutely, undeniably the essence of the Yanagawa adventure. Set everything else aside for a moment; this is what matters most. A donko-bune is a low, flat-bottomed boat, pushed forward by a single, remarkably long bamboo pole skillfully wielded by a boatman called a ‘sendo’. This isn’t some high-tech excursion with an incessant audio guide. This is pure, genuine analogue magic.

Your trip starts at one of several launch points around the city. As you step aboard and settle onto the tatami-covered floor, the noise of the modern world swiftly fades away. The sendo, often an experienced local whose face carries countless stories, offers a respectful nod. Wearing a traditional happi coat and a conical straw hat, they embody this centuries-old tradition. With a gentle press of the pole against the canal bed, you’re underway. The first thing you’ll notice is the sound—or rather, the quiet. No engine noise, just the steady splash of the pole, the soft lapping of water against the boat, and the rustling of leaves in the breeze. It’s an immediate balm for the soul.

The 70-minute, 4.5-kilometer journey is a feast for the senses in the best way. You’ll glide beneath weeping willows whose branches delicately brush the water’s surface. You’ll pass ancient, moss-covered stone walls of old samurai residences, their foundations embedded right into the canal. Look closely, and you’ll spot large, colorful koi carp swimming alongside, their scales shimmering in the dappled sunlight. The canals are narrow, often barely wide enough for the boat, making the experience feel intimate and personal. You’re not just admiring the scenery; you’re fully immersed in it.

One of the most exciting and iconic moments of the ride is steering under the extremely low bridges. Some are so low that everyone on board, including the sendo, must lie flat to avoid hitting their heads. It’s a shared moment of gentle suspense, followed by laughter as you reemerge into the sunlight. The sendo’s skill is truly impressive. They skillfully navigate tight bends, slip under these impossibly low bridges, and control the boat’s momentum with apparent ease — all using just that one bamboo pole. They are genuine experts, and their quiet confidence is a big part of the experience.

But the sendo offers more than navigation. They’re your guide and entertainer. While most of their commentary may be in Japanese, their gestures, infectious enthusiasm, and the sheer beauty of what they highlight transcend any language barrier. Then comes the moment that truly transforms the ride into something unforgettable: the sendo’s song. As you drift through a stretch of canal bordered by tall walls or beneath a stone bridge with perfect acoustics, the sendo often pauses, clears their throat, and begins to sing. They perform traditional regional folk songs, often melancholy and beautiful pieces penned by Yanagawa’s most famous poet, Hakushu Kitahara. The sound of their raw, heartfelt voice echoing off the water and stone is hauntingly beautiful. It’s a moment of pure, undiluted cultural immersion, a connection to the city’s soul that gives you goosebumps. This isn’t merely a boat ride; it’s a performance, a history lesson, and a moving work of living art all at once.

The Poet Laureate of the Canals: The Spirit of Hakushu Kitahara

To fully immerse yourself in the Yanagawa experience, you need to become familiar with its most renowned resident, Hakushu Kitahara. You simply cannot separate the poet from the place, nor the place from the poet. His spirit is woven into the very water of the canals. Born in Yanagawa in 1885, Hakushu became one of modern Japan’s most influential and prolific poets. He was a literary rockstar—an expert in the traditional ‘tanka’ form, a pioneer of modern free-verse poetry, and a beloved writer of children’s songs and nursery rhymes still sung by children across Japan today.

Hakushu’s importance to understanding Yanagawa lies in the fact that the city was his muse. His childhood was spent playing along these very canals, with the sights, sounds, and scents of his hometown forming the foundation of his creative world. His poetry brims with vivid images of weeping willows, the rainy season, dragonflies skimming the water’s surface, and the rhythm of life shaped by the waterways. He wrote about the ‘unohana’ flowers blooming on canal banks and the melancholy songs of the sendo. Reading his work feels like a backstage pass to Yanagawa’s emotional landscape, adding depth to everything you see. That gnarled willow tree you’re drifting past? He likely wrote a poem about it.

To truly connect with his legacy, a visit to the Hakushu Memorial Museum is essential. Located next to his preserved birthplace, the museum isn’t just a dry collection of manuscripts; it’s a beautifully curated exploration of his life and mind. You can view his personal belongings, calligraphy, and displays that bring his poems to life. It offers the context needed to appreciate how deeply this watery world influenced his artistic vision. Walking through his childhood home, you can almost sense the presence of the young boy who would go on to capture the soul of his city in words.

This connection is vividly celebrated during the Hakushu Festival, held annually from November 1st to 3rd. The festival is a grand tribute to his life and work, highlighted by an evening water parade. Dozens of donko-bune boats, illuminated with paper lanterns, glide down the canals in procession. The event features poetry readings, music performances on the water, and a stunning fireworks display. It is Yanagawa at its most enchanting and atmospheric, a tribute that feels deeply personal and rooted in the town’s identity. Even if you visit outside the festival, Hakushu’s spirit is always present. When your sendo sings one of his songs during your boat ride, you are not merely hearing a folk tune; you are participating in a living tradition, a direct connection to the poet who so perfectly captured the beauty and melancholy of this remarkable water city. His words give voice to the scenery, transforming a simple boat ride into a profound poetic experience.

Beyond the Boat: Getting Your Steps in and Your Eats On

As your 70-minute float trip gently comes to an end at the disembarkation point, you might assume the Yanagawa experience is finished. You’d be very mistaken. The boat ride serves as a perfect appetizer, while the main event is exploring the rest of this historic treasure on foot. The boat tour concludes at a place called ‘Ohana,’ which should be your first stop. Ohana is more than just a building; it’s the former villa and estate of the Tachibana clan, the ruling family of Yanagawa. This breathtaking complex offers a tangible connection to the town’s aristocratic heritage.

The highlight here is the Shoto-en garden, designated a National Site of Scenic Beauty – far from an ordinary backyard. Created in 1910, the garden incorporates the canal waters to form a stunning pond, accented with artfully placed rocks and over 280 meticulously groomed pine trees, all framed by the estate. The name ‘Shoto-en’ means ‘garden of pine-crested waves,’ and it’s easy to see why. The view from the grand hall of the main residence is one of the most iconic scenes in all of Kyushu. Next to this traditional Japanese masterpiece stands the Seiyokan, a magnificent two-story Western-style mansion that once hosted distinguished guests. The stark contrast between the elegant Japanese architecture and the grand, nearly Rococo Western building offers a fascinating glimpse into the Meiji era’s rapid modernization and embrace of global influences. You can explore both buildings, wandering through the lavish rooms and imagining the lives of counts and countesses who once resided here.

After soaking in all that history, you’ve likely worked up an appetite. And in Yanagawa, that means just one thing: ‘Unagi no Seiro-mushi.’ This local delicacy is the town’s soul food and a must-try culinary tradition. It’s not your typical grilled eel over rice. Seiro-mushi is a unique specialty where eel fillets are grilled, glazed with a sweet and savory soy-based sauce, layered over rice mixed with the same sauce, then steamed together in a rectangular bamboo steamer basket. The outcome is pure magic. The steaming makes the eel incredibly tender and fluffy, infusing the rice with the rich, smoky flavor of the unagi and its sauce. Served piping hot in the lacquered box it was steamed in, the moment you lift the lid and the fragrant steam rises, you know you’re about to enjoy something special. There are numerous unagi restaurants around Yanagawa, many housed in historic buildings overlooking the canals. Finding one and sitting down for an authentic unagi lunch is just as essential to the Yanagawa experience as the boat ride itself.

With a full stomach, it’s time to wander. The canal area is a treasure trove of charming streets. Look out for ‘namako-kabe,’ the distinctive black and white tiled walls that symbolized wealth during the Edo period. These can still be seen on old storehouses and samurai residences. Stroll through peaceful residential neighborhoods, peek into small local shrines, and simply lose yourself in the slow rhythm of life here. You’ll see locals tending their gardens, cycling along the waterways, and living in a way still deeply connected to the canals. It’s a chance to experience a side of Japan that feels genuine, unhurried, and far removed from the major tourist centers.

Dialing in the Seasons: The Best Time to Float

Yanagawa is truly a year-round destination. However, depending on when you visit, you’ll experience a completely different yet equally captivating atmosphere. The city’s mood changes dramatically with the seasons, allowing you to customize your trip to suit the vibe you’re seeking. Let’s break it down.

Spring is undoubtedly the peak season, largely because of one very special event: the ‘Yanagawa Hina-matsuri Sagemon Meguri’. Running from mid-February to early April, this festival offers Yanagawa’s distinct and spectacular twist on the traditional Hina-matsuri, or Doll Festival. While most of Japan celebrates by displaying elegant Hina dolls on tiered platforms, Yanagawa elevates the tradition with ‘Sagemon’—beautiful handmade decorations made up of colorful balls and intricate cloth figures representing auspicious symbols like cranes, rabbits, and cicadas, all strung together and hung from the ceiling. These are traditionally crafted by families wishing for the happiness and healthy growth of their newborn daughters. Throughout the festival, homes, shops, and public spaces across the city are adorned with these vibrant hanging displays, creating a visual feast. The festival culminates in the ‘On-hina-sama Water Parade,’ where children dressed in elaborate Heian-period attire ride in donko-bune, forming a floating imperial court on the canals. It’s a photographer’s dream and a truly enchanting experience.

In summer, the city transforms into a lush, vibrant jungle of green. The weeping willows reach their fullest, their long branches forming shady green tunnels over the canals. The air hums with the sound of cicadas, and the entire landscape feels alive and bursting with energy. Taking a boat ride at this time offers a welcome escape from the heat, as the water and shade provide a natural cooling effect. On early summer evenings, particularly around June, you might be fortunate enough to see fireflies dancing above the water, adding a touch of pure magic to the already dreamy setting.

Autumn is a strong contender for the best season. The oppressive summer humidity gives way to crisp, clear air, and the foliage begins to change. Maple and ginkgo trees lining parts of the canals burst into fiery shades of red, orange, and yellow. The reflection of the autumn colors in the calm water is simply breathtaking. As mentioned earlier, early November hosts the Hakushu Festival, celebrating the city’s beloved poet with its own lantern-lit water parade. The combination of stunning autumn scenery and rich cultural festivities makes this an excellent time to visit.

But don’t overlook winter. Winter in Yanagawa offers one of Japan’s most unique and cozy experiences: the ‘kotatsu boat’. From December to February, the donko-bune are equipped with kotatsu, which are low wooden tables covered by a heavy blanket with a heater underneath. You can snuggle beneath the warm blanket, perhaps sip some hot sake, and glide through the stark, quiet beauty of the winter landscape. The willow trees stand bare, creating an elegant, minimalist scene. With far fewer tourists, the experience feels deeply peaceful and intimate. Drifting silently down a canal while tucked into a warm kotatsu defines Japanese winter comfort—or a kind of ‘hygge’ with a Japanese twist. It’s such a unique and memorable experience, you might want to plan your trip around it.

The Practical Playbook: Your Guide to Nailing the Yanagawa Trip

Alright, you’re convinced. You’re ready to explore Japan’s Venice. Let’s get down to the details and logistics to ensure your trip goes smoothly—quite literally. Getting to Yanagawa is surprisingly simple, especially from Fukuoka, the largest city in Kyushu.

The easiest way to get there is by train. Head to Nishitetsu Fukuoka (Tenjin) Station in central Fukuoka City. From there, take the Nishitetsu Tenjin Omuta Line directly to Nishitetsu-Yanagawa Station. The limited express train is your best option, getting you there in about 50 minutes. Tip: keep an eye out for special ticket bundles from Nishitetsu Railway. They often offer deals combining your round-trip train fare with a kawakudari boat ride ticket, and sometimes even a meal voucher for an unagi restaurant. These packages are excellent value and simplify the whole process. Just buy one ticket and you’re ready for the day.

Once you reach Nishitetsu-Yanagawa Station, the boat departure points are just a short walk or quick taxi ride away. Most visitors start their journey near the station. Note that the classic kawakudari boat ride is a one-way trip, beginning upstream and ending about 4.5 kilometers downstream near the Ohana villa. Don’t worry about returning—boat companies have that covered. Free shuttle buses run regularly from the disembarkation point back to the starting area or train station. Alternatively, you can take a taxi or, if you’re up for it, enjoy a 45-minute walk back, which lets you discover new parts of the city.

Here are some insider tips to make the most of your day. Wear comfortable shoes, as you’ll do quite a bit of walking after the boat ride. In summer, a hat, sunglasses, and sunscreen are essential since the boats are open-air (though they provide traditional straw hats for shade). In cooler months, dress in layers. While cash remains king at many small businesses in Japan, most major spots in Yanagawa accept credit cards, but it’s wise to carry some yen for smaller purchases. Don’t worry if you don’t speak Japanese. While the boat guides (sendo) add a charming local touch with their stories, the visual experience is powerful enough to transcend language barriers. Just smile, nod, and soak it all in. Finally, decide how long you want to stay. Yanagawa works wonderfully as a day trip from Fukuoka, but to truly savor its slow-paced charm, consider an overnight stay at a local ryokan (traditional inn). Waking up in Yanagawa and taking an early morning stroll along the quiet canals before the crowds arrive is a whole new experience.

The Enduring Flow: A Final Reflection

As you depart Yanagawa, whether aboard the evening train back to Fukuoka or after a longer stay, a profound sense of tranquility lingers. This city is more than a collection of canals and historic buildings; it embodies a living philosophy. In a world that constantly urges us to move faster and optimize every moment, Yanagawa presents a gentle yet firm counterpoint. It softly suggests that beauty lies in slowness and wisdom in following the natural rhythm of life. The steady dip of the sendo’s pole in the water acts like a metronome, realigning your internal clock to a more human, sustainable pace.

A journey along the horiwari is a voyage into the heart of Japan, where practicality and poetry coexist as two sides of the same coin. The canals, originally created for defense and agriculture, have evolved into sources of art, inspiration, and peaceful reflection. Here, the deep bond between people and their environment is evident—a relationship of respect and harmony cultivated over four centuries. This connection shows in the skillful boatman, the meticulous gardens of Ohana, and the pride a chef takes in preparing the city’s renowned unagi dish. Yanagawa reminds us that the most profound experiences are often simple: the reflection of a willow on the water, the echo of a heartfelt song beneath a bridge, the flavor of a perfectly steamed meal. It is a city that does not demand attention but invites you to listen, observe, and simply be. In doing so, it leaves a lasting impression—a memory of a place where time, for a moment, flowed as gently as the canals themselves.