Yo, what’s up, fellow travelers! Li Wei here, coming at you from a place that’s basically a real-life time capsule. We’re talking about Uchiko, a low-key gem tucked away in the mountains of Ehime Prefecture on the island of Shikoku. Forget the neon chaos of Tokyo for a sec and picture this: a perfectly preserved street, over 600 meters long, lined with epic merchant houses from the Edo and Meiji periods. This isn’t some theme park; it’s the real deal. A town that got rich on wax and paper, and instead of tearing everything down, they decided to just… keep it. The result? A streetscape so authentic you’ll feel like you’ve main-charactered your way into a historical drama. The vibe is immaculate, a serene, golden-hued dreamscape where the loudest sounds are the gentle swoosh of a sliding paper door and the distant chirping of birds. For anyone looking to connect with a side of Japan that’s deep, artistic, and seriously beautiful, Uchiko is where it’s at. It’s a place that tells a story of craftsmanship, prosperity, and the quiet dignity of preserving one’s heritage. As someone who’s spent a lot of time exploring the historical threads connecting East Asia, Uchiko feels incredibly special—a dialogue between Japanese ingenuity and a universal appreciation for aesthetics and history. It’s a place that asks you to slow down, to look closer, and to just breathe in the centuries. So, let’s get ready to wander, because this town is a whole mood.

The Echoes of a Merchant’s Dream: Yokaichi-Gokoku District

Entering the Yokaichi-Gokoku preservation district is at the heart of the Uchiko experience. This is more than just a stroll along a street; it’s a full immersion. The very atmosphere feels different here, heavy with the scent of aged wood and the subtle, sweet aroma of the wax that shaped this town. The main street unfolds before you, curving gently and lined with two-story buildings that are exquisite examples of traditional Japanese architecture. The color scheme is a calming blend of earthy plaster walls, dark-stained timber, and the detailed grey of fired roof tiles. There’s a deep sense of harmony in the design, a visual rhythm flowing smoothly from one structure to the next. What immediately catches your eye is the quiet confidence of the architecture. These buildings were more than just functional; they were bold statements. This was new money, merchant wealth, proudly displayed for all to witness. At a time when the samurai class still held sway, the affluence of towns like Uchiko signaled a shift in Japan’s social and economic order. Seeing these homes, it becomes clear that the merchants, the shōnin, were emerging as the new power holders, and their residences were their fortresses. This evokes memories of ancient merchant compounds in regions like Shanxi province in China, where affluent families constructed grand, fortified homes that served as both living quarters and symbols of commercial dominance. Here in Uchiko, the style is distinctly Japanese—perhaps more understated, emphasizing natural materials and subtle elegance—but the fundamental narrative of mercantile pride is a universal theme echoed throughout Asia.

As you begin your walk, your attention is drawn to the details. The most striking feature is the kōshi, or wooden latticework, adorning the fronts of the buildings. These weren’t mere decoration. Each pattern and design communicated information about the family’s business, their social standing, and even the particular kinds of goods they sold. The refinement of the lattice was a quiet display of the owner’s wealth—the more delicate and intricate the woodwork, the more skilled (and costly) the carpenter they employed. Next, you notice the walls, especially the distinctive namako-kabe or ‘sea cucumber walls.’ These consist of white plaster grids over dark grey tiles, forming a diamond pattern that is both visually striking and highly fire-resistant. Fire was the greatest threat to pre-modern Japanese towns, which were constructed almost entirely from wood and paper. The namako-kabe, typically found on storehouses (kura), served a practical purpose: protecting the family’s valuables from disaster. Another architectural boast is the udatsu, small tiled walls rising above the roofline between neighboring houses. Initially created as firebreaks, they soon became status symbols. Erecting an impressive udatsu was a costly endeavor, a clear message to neighbors that you were prosperous. As you stroll down the street, you can almost discern the social hierarchy of the town by comparing the size and complexity of each family’s udatsu. It’s a silent dialogue in wood and tile, a narrative of ambition and success unfolding across the rooftops.

Inside the Halls of Power: The Kamihaga Residence

To fully understand the extent of Uchiko’s prosperity, you absolutely must step inside the Kamihaga Residence. This is more than just a house; it is an expansive compound that functioned as the home, office, and factory for one of the town’s most influential wax merchant families. The Honhaga family, along with their branch, the Kamihaga, dominated Japan’s wax (mokuro) industry, and this residence stands as a testament to their power. It has been designated a National Important Cultural Property, and for good reason. From the moment you step inside, you are immersed in a world of exquisite craftsmanship. The sheer scale of the compound is astonishing. You wander through a maze of rooms with tatami mat floors, divided by beautifully painted fusuma (sliding doors) and delicate shoji (paper screens). The light filtering through the paper screens is soft and diffused, casting a gentle glow on the polished wooden beams and pillars that frame each space. The main residential areas are elegant and spacious, designed for entertaining important guests and conducting business, all while preserving a sense of domestic calm.

Yet the true wonder of the Kamihaga Residence lies in how it preserves the entire industrial process under one roof. You can follow the journey of wax from beginning to end. You’ll see the massive stone mills once powered by oxen to crush the berries of the haze (sumac) tree. You can step into the steaming rooms where the raw material was heated to extract wax, then explore the workshops where it was filtered, sun-bleached, and molded into pure white blocks that were shipped throughout Japan and even exported abroad. The museum within the compound excellently explains this process with detailed exhibits and life-sized dioramas. You can view the tools, workers’ clothing, and ledger books that recorded the family’s vast fortune. It offers a comprehensive view of an industry that has nearly vanished. Seeing the living quarters alongside the factory provides a profound insight into the life of a Meiji-era tycoon. Their work and home life were completely intertwined. This blending of commerce and domesticity is a powerful theme in East Asian merchant culture. The home was not only a sanctuary but also the very engine of the family’s prosperity—a concept as true in historical China as it was here in Uchiko.

The Soul of the Town: Uchiko-za Theater

If the merchant houses represent Uchiko’s brain, then the Uchiko-za Theater is undoubtedly its heart and soul. This venue is truly a showstopper. Built in 1916, this traditional Kabuki and Bunraku puppet theater is a stunning wooden structure that exudes a joyful, festive energy. It was constructed not by a wealthy lord, but through the collective investment of the town’s enthusiastic merchants and patrons, making it a genuine community project. For decades, it served as the cultural hub of Uchiko, hosting top performers from all over the country. After falling into disrepair, it was rescued from demolition by a passionate local movement and meticulously restored to its former glory in 1985. Today, it functions as a fully operational theater that still hosts performances, but on most days, visitors can explore every nook and cranny of this architectural marvel.

What a marvel it is. Walking through the Uchiko-za is an enchanting experience. You can sit in the masu-seki, the square box seats on the main floor where audiences once picnicked during all-day shows. You can gaze up at the soaring wooden ceiling and the delicate paper lanterns. But the real excitement lies behind the scenes. Visitors are encouraged to explore under the stage, a dark and cavernous space where you can manually turn the massive revolving stage, the mawari-butai. You can stand on the trapdoors (seri) used for dramatic entrances and exits of actors and scenery. You can even walk down the hanamichi, the long walkway extending from the stage through the audience—a key element in Kabuki that breaks the fourth wall and brings actors right into the crowd. Standing on the hanamichi and looking back at the stage, you can almost hear the roar of the crowd and the clang of wooden clappers signaling the start of a play. It’s an incredibly immersive experience. The ingenuity of the stagecraft, all operated with manual, wooden machinery, is astonishing. It reflects a deep tradition of theatrical arts with parallels to the elaborate stage designs of Chinese opera. The Uchiko-za is not a static museum exhibit; it feels alive, pulsing with the ghosts of a thousand performances and ready for the next one to begin. It’s a powerful reminder that the wealth earned from wax and paper was reinvested into cultivating a rich cultural life for the town’s residents.

The Art of Light and Words: Uchiko’s Enduring Crafts

Uchiko’s identity is deeply intertwined with two major crafts: Japanese wax (mokuro) and washi paper. The town’s story is, in essence, the story of these materials. Although the large-scale production of the Meiji era has vanished, the spirit of this craftsmanship remains alive through the dedication of a few skilled artisans. To truly connect with Uchiko, one must engage with these enduring traditions. The wealth that built the magnificent Yokaichi-Gokoku district primarily came from the production and trade of mokuro, a vegetable wax extracted from the fruit of the haze (sumac) tree. This was no ordinary wax; it was a premium product, valued for candles that emitted a bright, steady flame with minimal smoke or dripping, making them ideal for use in temples, affluent homes, and the pleasure quarters of major cities. The process was demanding, requiring great skill and labor—from harvesting the berries to crushing, steaming, pressing, and purifying the wax. The final product was a source of great pride and profit for Uchiko’s merchants.

You can witness this craft’s legacy at Omori Warosoku, a small, family-run candle shop operating for over 200 years. Here, you can observe a master craftsman handcrafting warosoku (traditional Japanese candles). The process is captivating. The artisan takes a wick made of washi paper and rushes, then skillfully applies layer upon layer of molten haze wax using only his hands, constantly rotating the wick to shape a perfect candle. It’s a rhythmic, almost meditative process passed down through generations. The candles they create are works of art, and watching their creation offers a deep appreciation for the skill involved. It’s a direct and tangible link to the industry that put Uchiko on the map. This devotion to a single refined craft reminds me of master artisans in China who dedicate their lives to perfecting skills such as porcelain glazing or silk embroidery. It reflects a shared cultural value in East Asia—the belief that true mastery is a lifelong pursuit.

The other cornerstone of Uchiko’s economy was washi paper. The nearby town of Ozu, part of the same cultural and economic sphere, gained particular renown for its high-quality paper, with Uchiko serving as a key distribution center. Made from the fibers of the kozo (paper mulberry) bush, Ozu-washi is strong, beautiful, and remarkably versatile. It was used in everything from shoji screens in homes to calligraphy, woodblock prints, and official documents. In some local workshops, you can still see the traditional paper-making process or even try it yourself. This involves soaking and beating the plant fibers into pulp, which is then mixed with water and a binding agent in a large vat. The papermaker uses a bamboo screen to lift a thin layer of slurry, skillfully shaking it to ensure the fibers interlock evenly before laying the wet sheet to dry. The resulting paper carries a warmth and texture that machine-made paper cannot replicate. Holding a fresh sheet of washi feels like holding a piece of nature transformed by human hands. It’s the paper that forms the walls of the houses you pass, the pages of the books recording merchants’ profits, and the wicks of the candles that lit their nights. To understand these two crafts is to grasp the very soul of Uchiko.

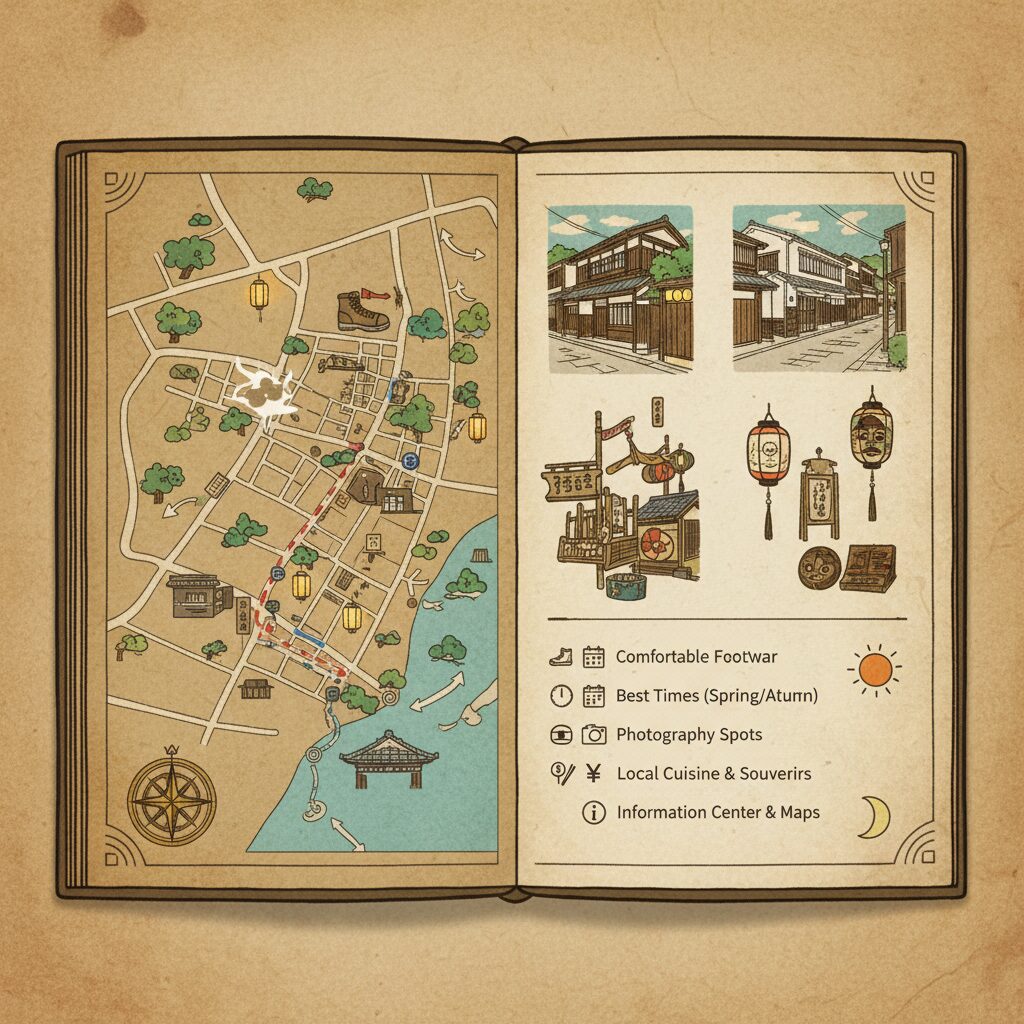

Crafting Your Uchiko Journey: A Narrative Walk

The best way to experience Uchiko is on foot, at a leisurely pace. Imagine the perfect day: you begin your journey at JR Uchiko Station, a modern and understated gateway to the past. Your first walk, heading toward the Oda River, leads you through the town’s more contemporary area—a quiet, pleasant residential neighborhood. This contrast is important, as it makes your arrival in the Yokaichi-Gokoku district feel all the more dramatic. Crossing the bridge over the river, the atmosphere shifts. The buildings grow older, the pace slows, and suddenly, you arrive at the preserved street that unfolds before you.

Your first stop should be the Uchiko History and Folklore Museum, also called the Museum of Commercial and Domestic Life. Set in a former pharmacy, this museum offers an ideal introduction to your visit. It provides essential context, explaining the history of the wax trade and the architectural features you will see—a sort of cheat sheet before you explore. Well prepared, you can now delve into the main street. Take your time. Don’t just move from point A to B. Look through open doorways. Admire the variety of latticework styles. Notice the udatsu. Feel the texture of the aged wooden posts. Many of these houses remain private residences, so respect is important, but the ground floors of several have been converted into charming cafés, craft shops, and small museums.

Set aside at least a couple of hours to explore the Kamihaga Residence. This large complex offers a chance to soak in both the elegant living quarters and the intriguing wax museum. Afterward, continue along the street to the Uchiko-za Theater. The guided tour is highly recommended, as the staff will demonstrate the remarkable stage mechanisms—an interactive experience that truly brings the theater to life. Following the theater, it’s a good time for a break. Seek out a traditional teahouse, or kissaten, located in one of the old merchant buildings. Sitting on a tatami mat, sipping matcha tea, and gazing into a small, secluded courtyard garden is an authentic Uchiko moment—a slice of pure zen.

In the afternoon, visit the Omori Warosoku candle shop to watch the artisans at work. The delicate aroma of wax and the craftsmen’s quiet concentration create a powerful sensory memory. Finally, as the afternoon sun casts long shadows along the historic street, simply wander. Explore the side alleys and discover small shrines hidden between houses. The golden hour light on the old plaster walls is breathtakingly beautiful—a perfect, peaceful conclusion to a day spent walking through history.

The Flavors of the Region: What to Eat in Uchiko

No trip to Japan is complete without fully immersing yourself in the local cuisine, and Uchiko, though small, presents delicious regional specialties that showcase the bounty of the surrounding land and sea. Ehime Prefecture is renowned for its citrus fruits and flavorful sea bream (tai), which feature prominently on local menus. Instead of vast restaurant districts, you’ll find small, intimate eateries, often family-operated for generations and sometimes housed within historic buildings. This makes dining in Uchiko an experience that nourishes both body and soul.

One must-try dish of the region is Taimeshi. There are two main versions of this sea bream rice dish in Ehime. The style most common in the southern part of the prefecture, including Uchiko, serves fresh sea bream sashimi over hot rice, topped with a savory sauce made from soy sauce, egg yolk, and dashi broth. It’s a simple yet incredibly flavorful dish that highlights the freshness of the fish. Another local favorite is Jakoten, a fried fish cake made from small, whole fish ground into a paste and deep-fried. It has a rustic, savory taste and is a popular snack or side dish.

For a heartier meal, seek out a restaurant offering a kaiseki or set menu featuring local, seasonal ingredients. Many places take pride in using vegetables grown in the mountains around Uchiko, river fish caught in the Oda River, and other hyper-local products. This is your opportunity to savor the true flavors of the region. A meal might include grilled sweetfish (ayu), simmered mountain vegetables (sansai), and locally made tofu. For something different, some establishments serve dishes with locally raised pork or chicken, often prepared with creative blends of traditional and modern techniques. And don’t forget to pair your meal with local sake. The pure mountain water of Shikoku is ideal for sake brewing, and Ehime produces excellent varieties that are clean, crisp, and pair beautifully with the cuisine. Dining in Uchiko means enjoying simple, high-quality ingredients in a setting rich with history. It’s slow food at its finest.

Practicalities and Pro Tips for Your Visit

Reaching Uchiko is part of the experience. The town is situated in Ehime Prefecture on the island of Shikoku. The most common way to get there is from Matsuyama, the prefectural capital. From JR Matsuyama Station, you can board the Limited Express Uwakai train on the Yosan Line, which goes directly to JR Uchiko Station. The trip takes around 25-30 minutes and offers scenic views of the Ehime countryside. If you’re traveling from mainland Japan, take the Shinkansen (bullet train) to Okayama, then transfer to the Limited Express Shiokaze train that crosses the impressive Great Seto Bridge to Matsuyama, where you can make the final connection to Uchiko. Although it may feel slightly off the beaten path, the excellent Japanese rail system ensures a smooth and pleasant journey.

The best time to visit Uchiko varies depending on your preferences. Spring (late March to April) is beautiful, with cherry blossoms adding vibrant pink hues to the landscape, though it can be busier. Summer (June to August) is lush and green but often hot and humid. Autumn (October to November) is arguably the most favorable season, offering mild temperatures and stunning fall foliage in the surrounding mountains, providing a breathtaking backdrop to the historic town. Winter (December to February) is calm and peaceful. The town is much quieter, allowing you to enjoy the crisp winter air. There is a unique charm to the old streets on a calm, cold day. Uchiko also hosts several festivals throughout the year, such as the Uchiko Bamboo Festival in August, which are worth checking out if you want to experience the town at its liveliest.

A few final tips for your visit: Wear comfortable walking shoes, as you’ll be doing a lot of walking, and some old buildings require you to remove your shoes, so slip-on shoes are especially convenient. Bring cash. While more places now accept credit cards, many smaller shops, eateries, and admission booths still operate on a cash-only basis. Most importantly, give yourself plenty of time. Don’t try to rush Uchiko as a quick half-day trip from Matsuyama. To truly savor its atmosphere, you need to slow down and match the town’s pace. Consider staying overnight. Waking up in Uchiko and having the historic streets nearly to yourself in the early morning is an enchanting experience. Several lovely ryokan (traditional inns) and guesthouses in town will complete your immersive journey into the past.

A Final Reflection: The Quiet Power of Preservation

As you leave Uchiko, heading back toward the station and the modern world, a profound sense of respect lingers with you. Respect for the artisans who honed their crafts over centuries. Respect for the merchants whose ambition and aesthetic vision shaped the town. And above all, respect for the generations of citizens who had the foresight and passion to preserve this remarkable piece of their history. In a world often fixated on novelty and relentless progress, Uchiko stands as a powerful testament to the importance of continuity. It serves as a reminder that the past is not something to be discarded, but a foundation upon which to build a meaningful future. The town is not a relic; it is a living, breathing community that has found a way to carry its heritage forward with grace and dignity. A walk through Uchiko is more than mere sightseeing; it’s a lesson in culture, economics, and the quiet strength of choosing to remember. It’s an atmosphere that stays with you long after you’ve boarded the train and sped away, carrying the scent of old wood and sweet wax in your memory. It’s a place that touches your soul. Truly iconic.