Yo, what’s up. Ryo here. Let’s talk about those wooden dolls. For real. You’ve seen them. Maybe scrolling through your feed, sandwiched between shots of Shibuya Crossing and a steaming bowl of ramen, or maybe you saw one tucked away in a corner of a slick, minimalist apartment on a design blog. They’re simple. Cylindrical body, round head, no arms, no legs. Painted with a few delicate lines for a face and maybe some floral patterns. They’re Kokeshi. And if you’re like most people, your first thought was probably somewhere along the lines of, “Huh. Cute. Kinda… blank, though? What’s the deal?” You might’ve picked one up, felt its smooth, light wood, and put it back down, feeling like you were missing a piece of the puzzle. It’s an object that feels both intensely Japanese and completely unreadable at the same time. Is it a toy? Is it art? Is it just a souvenir that’s been around forever? The answer is yes, and also, it’s way deeper than that. These dolls aren’t just shelf-sitters; they’re a whole mood, a physical story about a specific part of Japan, a philosophy of making things, and a craft culture that’s both ancient and fighting to stay relevant. To really get Kokeshi, you have to go past the gift shop and into the headspace of the makers, into the workshops scattered across the mountains of northern Japan where the air smells like sawdust and tradition. It’s a scene that’s low-key one of the most authentic windows into the Japanese soul you can find. So, let’s ditch the surface-level stuff and dive deep into the world of Kokeshi. Let’s figure out why these simple wooden figures have such a hold, what their silent expressions are really saying, and what the whole maker vibe around them tells us about Japan itself. It’s a story about place, people, and the beauty of keeping things simple. Let’s get it.

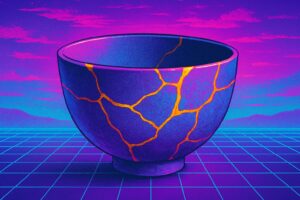

This philosophy of embracing simplicity and imperfection in craftsmanship is a thread that runs deep in Japanese culture, much like the art of kintsugi.

The OG Origin Story: More Than Just a Souvenir

First and foremost, you need to understand that Kokeshi didn’t originate in a design studio in Tokyo. Instead, their story begins far up north, in a region called Tohoku. Picture deep winter snow, lush green mountains in summer, and plenty of onsen—natural hot springs. For centuries, people, especially farmers and laborers, journeyed to these onsen towns not for brief vacations, but for a toji—an extended hot spring cure. They stayed for weeks or even months, soaking in mineral-rich waters to heal their weary bodies after a year of hard work. The atmosphere was therapeutic, restorative, and unhurried. In these towns, local woodworkers, known as kijiya (literally ‘wood-worker’), who typically crafted bowls and trays, began turning their lathes to produce a new item: simple wooden dolls. These were intended as omiyage, or souvenirs, for onsen visitors to take home. They served as mementos of their healing experience, small reminders of the mountains to carry with them. This background is crucial. Kokeshi emerged from a culture of wellness and a deep bond with nature. The wood, usually from Dogwood or Japanese Cherry trees, was locally sourced. It was what the artisans had readily available—a direct product of the surrounding forests. The process of shaping this raw, natural material into smooth, comforting forms reflects the very purpose of the onsen—transforming something raw and worn (a person or a piece of wood) into something whole and soothed. They were also regarded as talismans for children, believed to bring good luck and hopes for a healthy harvest. Their simple, rounded shapes were perfect for a baby’s grasp, making them one of Japan’s original folk toys. This is not merely a product; it’s the byproduct of a whole lifestyle, a particular time and place where community, nature, and craftsmanship were inseparably connected. Thinking of a Kokeshi as just a ‘souvenir’ is like calling a hand-thrown ceramic mug simply a ‘cup.’ It overlooks the entire meaning, the human touch, and the strong sense of place embedded within it.

Deconstructing the Vibe: The “No Arms, No Legs” Philosophy

Alright, let’s confront the obvious question: the minimalist design. Why a simple cylinder? Why no limbs? To a Western eye used to dolls that are miniature, hyper-realistic figures, Kokeshi can appear almost alien or incomplete. But this isn’t due to a lack of skill or an inability to carve arms. It’s a deliberate choice, rooted deeply in fundamental Japanese aesthetic principles visible everywhere once you know where to look. Here, we delve into the deeper cultural framework at play. The key idea is yohaku no bi, the beauty of empty space. The concept is that what isn’t there holds as much importance as what is. The unpainted wood, the simple lines, the absence of arms—this isn’t emptiness but potential. It invites your mind, your imagination, to fill in the blanks. The doll doesn’t offer a complete story; it provides a prompt. It doesn’t command attention but rather exists quietly. This ties into related concepts such as wabi-sabi, the appreciation of imperfection and impermanence, and shibui, a subtle, unobtrusive beauty. A Kokeshi isn’t striving to be a flawless human replica. It embraces the natural wood grain, the slight irregularities in the hand-painted lines. It is content simply to be. This marks a fundamental philosophical divergence from the Western tradition of mimesis—that art is an imitation of reality. Japanese aesthetics tend to capture the essence, the ki or spirit of something, rather than its literal form. By omitting distracting details like limbs and elaborate poses, the Kokeshi craftsman directs your focus to what truly matters: the gentle curve of the body, the face’s expression, and the texture of the natural material. It’s a masterclass in minimalism. It’s not about what’s absent but what remains. It serves as a form of visual meditation, encouraging you to slow down and appreciate the simple, the quiet, the essential. The Kokeshi doesn’t need arms to convey presence; its stillness is its strength.

It’s a Regional Thing: The 11 Kokeshi Clans

Now, this is where it truly gets fascinating, and you begin to appreciate the real depth of the craft. A Kokeshi is never just a Kokeshi. Saying so would be like saying a sandwich is just a sandwich. Traditionally, there are 11 distinct styles, or kei, of Kokeshi, each tied to a specific onsen town or region within Tohoku. This is hyper-localism at its peak. The shape of the head, the curve of the body, the unique painted patterns—none of these were random artistic decisions. Instead, they became a kind of visual signature, a dialect spoken through wood and paint, instantly recognizable to those familiar with them. An artisan from Naruko creates a Naruko-style Kokeshi because that’s the visual language of their home. These skills have been passed down directly from master to apprentice, often within the same family, across generations. Visiting these workshops is more than just shopping; it’s like stepping into distinct cultural micro-nations, each with its own unique aesthetic heritage. This is the maker ethos in its purest form—not a fleeting trend, but a living lineage.

Naruko-kei: The Iconic Star with the Squeak

If Kokeshi had a leading figure, it would likely be the Naruko style. Originating from the renowned Naruko Onsen in Miyagi Prefecture, it is one of the most iconic and adored types. The body features a distinct, slightly narrowed waist, lending a subtle hourglass silhouette that feels graceful. The shoulders are broad and defined. Patterns often include chrysanthemums, a symbol of autumn and the imperial family, rendered with vivid, confident brushstrokes. But the real signature detail, the feature beloved by those in the know, is the head. A Naruko Kokeshi’s head is attached with a special technique so that when turned, it makes a charming squeaky sound—kyu-kyu. Locals say it resembles a baby’s cry, linking back to the dolls’ role as protective charms for children. This interactive element is pure genius, adding playfulness and character—a secret handshake between doll and owner. This small detail holds a world of craftsmanship and tradition. Holding a Naruko doll and turning its head connects you with a very specific, endearing piece of local identity.

Tsuchiyu-kei: The UFO Head and the Snake Eye

Traveling to Tsuchiyu Onsen in Fukushima, the Kokeshi style shifts dramatically. Tsuchiyu-kei dolls are instantly identifiable by their smaller heads and long, slender bodies. The head’s top often features a black circle with concentric rings, a pattern called janome, meaning “snake’s eye,” believed to ward off evil. It lends the doll an almost hypnotic, otherworldly appearance. The bangs are softly painted with a feathery fringe, and the body is adorned with flowing lines created by a spinning lathe, evoking movement and energy. Compared to the grounded, stable feel of a Naruko doll, the Tsuchiyu Kokeshi feels lighter, almost whimsical. It beautifully illustrates how different towns developed distinct aesthetic sensibilities, even when working with the same basic materials and forms. The Tsuchiyu artisan isn’t merely making a doll; they are continuing a conversation begun by their ancestors, using a shared visual vocabulary unique to their home.

Togatta-kei: The Big-Headed, Solemn Beauty

In Togatta Onsen, also in Miyagi, you encounter another distinct character. The Togatta-kei Kokeshi is recognized by its relatively large, cylindrical head perched atop a straight, slender body. It lacks a defined waist, giving it a stoic, columnar presence. The standout feature is usually the face and head decoration. The eyes are often crescent-shaped or simple arches, giving a gentle, nearly meditative expression. The head’s top is frequently adorned with a radial, flower-like design called tegara, usually in striking red, which radiates from the center. It’s a bold, graphic statement contrasting beautifully with the calm face. The body may feature chrysanthemums or plum blossoms, but the radiant head is the true centerpiece. A Togatta doll exudes regal composure and quiet confidence. It embodies the idea of finding profound beauty and expression within strict formal limits.

Hijiori-kei: The Sunshine Doll

From Hijiori Onsen in Yamagata Prefecture comes a Kokeshi that radiates pure sunshine. The Hijiori-kei is distinguished by its yellow body, often decorated with square chrysanthemum patterns. The eyes are crescent-shaped, like Togatta’s, giving the doll a cheerful, smiling look. Its body shape resembles the Naruko style with an indented waist, but the overall vibe is brighter and more optimistic. According to local legend, the onsen’s waters were discovered by a monk who saw a yellow light, inspiring the doll’s signature color. Whether fact or folklore, it reflects how these designs are deeply intertwined with local stories and identity. Holding a Hijiori Kokeshi feels like holding a small piece of the town’s sunny spirit. It’s a testament to how a simple choice of color can transform the mood and narrative of an object, firmly rooting it in its place of origin.

Inside the Workshop: The Scent of a Living Craft

To truly immerse yourself in the Kokeshi world, you must mentally step into an artisan’s workshop. Forget the spotless white walls of a modern gallery. Envision a small, rustic space, perhaps attached to the craftsman’s own home. The air is thick with the sweet, sharp aroma of wood shavings. Sunlight filters through a window, highlighting countless dust motes dancing in the air. This is more than just a production site; it is a sanctuary of skill, a place where tradition lives and breathes. Making a Kokeshi is a slow, deliberate dance between artisan and wood—a ritual refined over a lifetime.

Wood Whisperers: The Art of Patience

The journey of a Kokeshi begins long before it reaches the lathe. It starts in the forest. Artisans, or kokeshi-ko, possess deep knowledge of their primary material. They handpick logs of Dogwood, Cherry, or Mizuki wood, searching for just the right age and quality. These logs must then be seasoned—naturally air-dried over periods ranging from six months to several years. This slow drying phase is essential; it prevents cracking or warping later. This step embodies patience. It’s a profound lesson in working with nature, not against it. The artisan cannot rush the wood—they must honor its timeline. This deep, almost reverent relationship with the raw material exemplifies Japanese craftsmanship, or monozukuri. The finished doll carries within its grain the memory of the seasons it endured while drying—a silent history embedded in the wood.

The Lathe Dance: From Log to Figure

When the wood is ready, the real magic begins. The artisan mounts the block onto a lathe, a machine that has been central to this craft for generations. The lathe’s startup is the workshop’s heartbeat. Steady hands wield specialized chisels and gauges to shave away the wood. Though this appears simple, it demands immense skill and muscle memory. As the wood spins rapidly, shavings fly, blanketing the floor in fragrant curls. There is no blueprint or computer-aided design. The artisan works from a mental image, an ideal shape passed down through lineage. They feel the form through the tool in their hands. In minutes, the rough log transforms into the smooth, elegant silhouette of a Kokeshi—a perfect cylinder with a rounded head. It’s a mesmerizing performance, a physical dialogue between human and machine, skill and material.

Brushstrokes of Identity: Giving the Doll its Soul

At this stage, the shaped wooden form is a blank canvas. The final and arguably most important step is painting. Using fine brushes, sometimes crafted from a single hair, the artisan breathes life into the Kokeshi. Here, regional dialects come alive. The unique curve of the Naruko chrysanthemum, the concentric circles of the Tsuchiyu snake’s eye, the vivid red of the Togatta head—these details are painted freehand with precision honed over a lifetime. The lines are swift, confident, and delicate. The palette often remains simple: black ink (sumi) and pigments in red, green, or yellow. The face is usually painted last. With just a few strokes—two arcs for eyes, a dot for a nose, a small curve for a mouth—an entire personality emerges. It may appear serene, cheerful, shy, or solemn. This moment, when the artisan gives the doll its expression, is considered the giving of its soul. It is the final breath of life in the wood. After applying and buffing a coat of wax to a soft sheen, the Kokeshi is complete, ready to carry its story into the world.

The Modern Kokeshi Glow-Up: Not Your Grandma’s Doll

It would be easy to view this entire scene as a beautiful yet fading art form, a remnant of a past era. For a time, that narrative appeared accurate. Traditional Kokeshi workshops faced the same hurdles as many other old-fashioned crafts in Japan: an aging master population and fewer young individuals willing to dedicate themselves to the lengthy, demanding apprenticeship. The souvenir market evolved, and these understated dolls were often overshadowed by flashier options. However, dismissing Kokeshi now would be a grave error. In recent years, something remarkable has occurred: Kokeshi has experienced a revival. The craft is not merely surviving; in many respects, it is flourishing by adapting and evolving. This transformation is taking place on two fronts: within the tradition itself and entirely outside of it. A new generation of artisans and designers has fallen for the Kokeshi form, sparking a creative surge that has revitalized the scene. This process isn’t about abandoning the old ways but about adding new branches to a very old tree. The result is a vibrant landscape where tradition and innovation coexist, crafting an exciting new chapter in the Kokeshi story. It’s proof that a craft with deep roots can still reach for the sun.

Sosaku Kokeshi: Breaking the Mold

Alongside the 11 traditional styles, an entirely new category has emerged: sosaku kokeshi, or ‘creative Kokeshi.’ This movement began after WWII, when individual artists started using the Kokeshi form as a canvas for personal expression, free from the strict conventions of the traditional kei. Today, the sosaku scene is flourishing. These artisans experiment with exotic woods, unconventional paints, and completely novel shapes. You might find a Kokeshi with a body carved into an intricate pattern, one painted to resemble a cat or an owl, or one that is abstract and sculptural. These creations are less folk craft and more art objects. They’ve allowed Kokeshi to enter the realm of contemporary design and art collecting, attracting an entirely new audience. This movement is vital because it demonstrates that Kokeshi is not a static relic confined to a museum. It is a living, breathing art form—a versatile medium that modern creators can reinterpret and reimagine. It honors the essence of Kokeshi—the turned wood and simple form—while pushing its boundaries in thrilling new directions.

The Global Crossover: From Tohoku to Your Timeline

Another key factor in the Kokeshi revival is, as you might expect, the internet. Social media platforms like Instagram and Pinterest have become virtual galleries for these stunning objects. The minimalist aesthetic of Kokeshi perfectly suits today’s curated, design-savvy feeds. People are drawn to their simple charm, handmade quality, and the stories behind them. This global exposure has generated an international market. You no longer need to visit a remote onsen town in Tohoku to admire or purchase a Kokeshi. Online stores and international retailers have made them available to a worldwide audience that values authenticity and craftsmanship. Moreover, Kokeshi are appearing in unexpected places—as design elements in fashion, characters in animations, and sources of inspiration for modern illustrators. This crossover appeal is introducing Kokeshi to a generation that might never have encountered them otherwise, securing their cultural relevance for the future. It’s a wonderful example of how a deeply local craft can find a global home without losing its soul.

So, Why Do They Matter? The Takeaway Vibe

So, after all that, let’s return to the original question. What’s the story behind these simple wooden dolls? Why should they matter to you? The truth is, Kokeshi are far more than they appear at first glance. They represent a quiet rebellion against our modern world of mass production and digital distraction. Each doll serves as a physical link to a specific place, a tangible fragment of a town’s history and identity. Holding one feels like holding a story passed down through generations of artisans. They embody a deeply Japanese design philosophy—that simplicity is not absence, but strength; that beauty lies in natural materials and imperfect, human touches; and that empty space invites the imagination to roam. They stand as a testament to the remarkable resilience of traditional craft, demonstrating how something old can confront the risk of fading away and find a way to reinvent itself, becoming cool and relevant once again on its own terms. The next time you see a Kokeshi, whether on a shelf in Japan or on your screen, take a moment to look closer. See beyond the simple shape. Imagine the snowy mountains of Tohoku, smell the sawdust in the workshop, hear the squeak of the Naruko head, and feel the steady hand of the artisan who brought it to life. You’re not just looking at a doll. You’re witnessing an entire vibe, a rich history, a whole philosophy of life, embodied in a perfect piece of wood.