To stand before a work of Japanese Metabolism is to witness a future that was, a magnificent and audacious dream cast in concrete. Born from the crucible of a nation reinventing itself after the Second World War, Metabolism was not merely an architectural style; it was a philosophical manifesto, a radical vision for a new way of living. It proposed that cities and buildings should not be static monuments, but living, evolving organisms, capable of growth, decay, and regeneration, much like the forests and seas that have shaped Japan’s cultural consciousness for millennia. The architects of this movement—visionaries like Kenzo Tange, Kisho Kurokawa, and Kiyonori Kikutake—were not just designing structures; they were sculpting a new Japanese identity, one that was defiantly modern, technologically advanced, yet deeply rooted in ancient philosophies of impermanence and renewal. They seized upon concrete, a material often associated with brutal weight and immutability, and imbued it with a startlingly organic vitality. They shaped it into clusters of cells, branching towers, and sprawling urban megastructures that seemed to pulsate with life. This is the essence of the ‘organic concrete’ vibe: a profound paradox where the cold, hard language of industrial modernism is used to write a poem about the cyclical nature of life itself. To explore Metabolism is to journey into the heart of post-war Japan’s soaring ambition, a time when a generation of thinkers dared to imagine a world where our built environment could live and breathe alongside us.

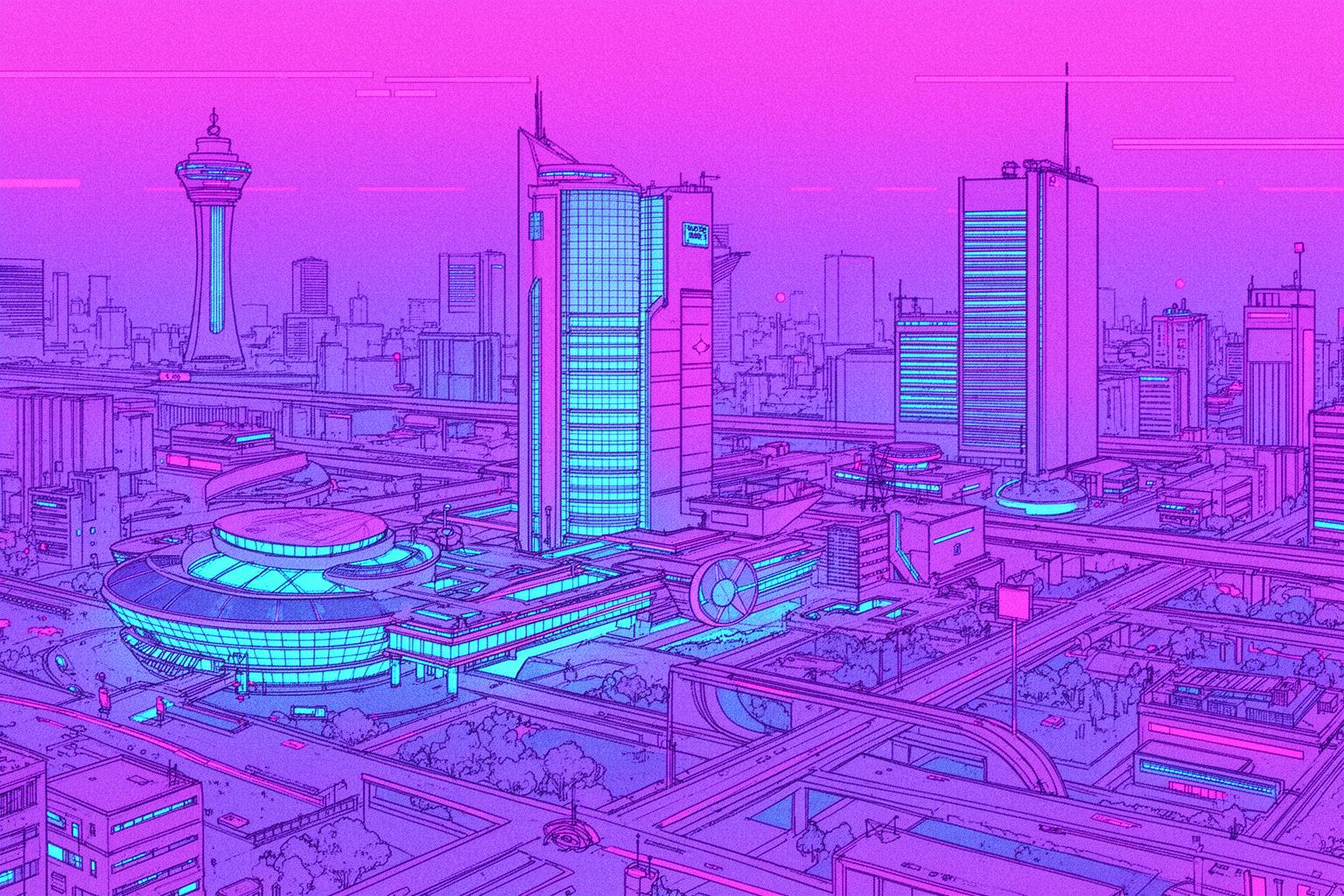

This vision of a living, evolving city finds a compelling modern echo in the concrete utopias of Roppongi Hills and Shiodome.

From Ashes to Organisms: The Historical Crucible of Metabolism

The story of Metabolism begins amidst the rubble and devastation of 1950s Japan. The physical destruction caused by the war was immense, yet it was accompanied by a profound psychological emptiness. The old certainties had vanished, and the nation faced the monumental challenge of not only rebuilding its cities but also forging a new identity for the modern era. This environment provided fertile ground for the movement’s emergence. There was a palpable energy, a collective urge to leap forward and construct a future that was not merely functional but deeply meaningful. Western modernism, with its clean lines and rational principles, offered a model; however, for a group of young Japanese architects, it fell short. They sought a path that honored Japan’s unique cultural heritage while embracing the dizzying possibilities of new technologies.

The movement officially debuted at the 1960 World Design Conference in Tokyo, a landmark event that placed Japan at the heart of the global design discourse. It was there that a small group—including Kisho Kurokawa, Kiyonori Kikutake, and architectural critic Noboru Kawazoe—presented their manifesto, “Metabolism 1960: The Proposals for a New Urbanism.” The name ‘Metabolism’ was a bold declaration of purpose, borrowed from the biological process of growth and transformation within a living cell. Their proposal was revolutionary. They argued that cities should be designed with a clear distinction between long-term infrastructure and short-term, replaceable components. They envisioned vast, permanent ‘major structures’—such as towering vertical cores, transportation spines, and artificial landmasses—that would form the city’s skeleton. Prefabricated, transient ‘minor structures’—individual housing capsules, office modules, and functional units—could then be plugged in and replaced as needed. This was architecture as a dynamic process, not a finished product. It was a city designed for change, recognizing the ongoing flux of modern life.

The Philosophical Foundation: Blending Shintoism, Buddhism, and Technology

To understand Metabolism means looking beyond its futuristic forms to the deeper currents of Japanese philosophy. The movement’s core ideas, while articulated in the language of modern technology and cybernetics, maintained profound connections to ancient traditions. The concept of cyclical renewal and acceptance of impermanence is a cornerstone of Japanese culture, most famously exemplified in the Shinto ritual of shikinen sengu at the Ise Grand Shrine. Every twenty years, the shrine’s wooden structures are carefully dismantled and rebuilt anew on an adjacent site. This ritual does not seek to preserve a physical object, but rather the techniques, spirit, and creative process itself. The Metabolists saw a clear parallel in their vision for the city. The individual capsule or building was not sacred; rather, it was the larger urban system—the ongoing process of growth and adaptation—that embodied true permanence.

This resonates deeply with Buddhist teachings on mujō, or the impermanence of all things. Whereas Western architecture—from pyramids to grand cathedrals—has often been a defiant gesture against time, seeking immortality through stone, Metabolism embraced the inevitable passage of time. Like the human body, a building would age, parts would wear out, and renewal would be necessary. This philosophical basis is what sets Metabolism so distinctly apart from its contemporaries. It was a uniquely Japanese modernism that found no contradiction in drawing inspiration both from a 1,300-year-old shrine and the latest theories of cellular biology. This synthesis was energized by the post-war era’s boundless optimism about technology. The architects were captivated by the potential of mass production, prefabrication, and systems thinking to address urgent urban challenges—from housing shortages to rapid population growth. They believed that technology, guided by a philosophy of organic transformation, could create a more humane and adaptable urban environment.

The Architects of Tomorrow: Tange, Kurokawa, and the Metabolist Circle

Although Metabolism was a collaborative movement, it was defined by the remarkable vision of a few key figures who, through both their realized and unrealized projects, gave tangible form to these radical ideas. They were simultaneously pragmatists and poets, addressing concrete urban planning challenges while envisioning solutions on an almost mythological scale.

Kenzo Tange: The Patriarch and His Urban Megastructures

Kenzo Tange is regarded as the mentor and spiritual father of the Metabolist group. Already an established and internationally acclaimed architect, his work and theoretical investigations laid the groundwork upon which younger architects built. Tange excelled at thinking on a grand scale, focusing not only on individual buildings but on entire urban ecosystems. His most breathtaking vision was the “Plan for Tokyo 1960.” Presented at the same conference that launched Metabolism, it depicted an extraordinary new city built along a central axis stretching across Tokyo Bay. This linear megastructure was designed to house ten million people, featuring a multi-layered transportation spine for cars and trains, from which office blocks and residential clusters would extend over the water. Conceived as a civic spine, the city was imagined as a vertebrate organism ready to grow and adapt. Although it was never realized, the audacity of the plan and its clear concept of a permanent core supporting flexible units became a hallmark of the movement.

A more tangible manifestation of his ideas is the Yamanashi Press and Broadcasting Center in Kofu, completed in 1966. Here, Metabolist theory takes on a powerful physical form. The building is not a monolithic block but a cluster of sixteen massive concrete cylinders serving as core infrastructure, housing stairs, elevators, and utilities. Inserted between and projecting from these strong shafts are functional spaces such as offices, studios, and terraces. The result is one of dynamic incompleteness, giving the impression that new modules could be added or removed anytime, allowing the building to evolve according to the company’s needs. Standing at its base and looking up, one senses the immense structural force of the cores, a permanent framework accommodating transient human activities. It is a masterpiece of structural expressionism and a pure embodiment of the Metabolist ideal.

Kisho Kurokawa: The Capsule as a Symbol of New Life

While Tange was the patriarch, Kisho Kurokawa was the movement’s most passionate ideologue and public figure. Fascinated by the individual’s place in mass society, he championed the capsule as the architectural unit of the future. His most iconic and controversial work was the Nakagin Capsule Tower, completed in Tokyo’s Shimbashi district in 1972. The building presented a striking sight: two concrete central cores clad with 140 prefabricated capsules that appeared to be snapped into place like Lego bricks. Each capsule was a small, self-contained living unit measuring just 2.5 by 4 meters, equipped with a bed, a compact bathroom unit, and built-in electronics including a television and reel-to-reel tape deck. It was designed for the ‘homo movens’—the modern, nomadic salaryman who maintained a primary residence in the suburbs but required a practical pied-à-terre in the city. Kurokawa envisioned these capsules, with an intended lifespan of 25 years, being individually unplugged and replaced with newer versions, enabling the tower to continually renew itself.

However, reality proved far more complicated. For various economic and technical reasons, the capsules were never replaced. Over decades, the building suffered gradual, then critical, decay. Residents faced leaks, asbestos issues, and failing systems. Yet, in its deterioration, the Nakagin Capsule Tower transcended its failure, becoming a cherished icon and a poignant symbol of a future that never fully materialized. Its slow decay served as a powerful, unintended reflection on Metabolist themes of decay and renewal. Before its emotional demolition in 2022, visiting the tower felt like stepping onto a 1970s sci-fi film set. The compact ingenuity of the capsules, the circular windows framing city views, and the building’s unusual form combined to create an atmosphere of melancholic futurism. Its life and demise have secured the tower a tragic yet beautiful place in architectural history as a monument to a utopian dream.

Beyond the Big Two: Kikutake, Maki, and the Collective Vision

Metabolism was never solely about two architects. It was a constellation of brilliant minds. Kiyonori Kikutake was obsessed with the ocean as a new frontier for human habitation. His unbuilt “Marine City” project from 1958 proposed floating cities with towering residential structures and artificial agricultural islands to address Japan’s land scarcity. On a more practical level, his own home, the Sky House (1958), was a pioneering example of Metabolist principles. A single concrete box raised on four massive piers, it featured a flexible interior and a system of replaceable modules called ‘movenettes’ for the kitchen and bathroom, anticipating the capsule concept. Fumihiko Maki, another core member, introduced the idea of “Group Form,” focusing less on plug-in technology and more on how clusters of buildings could evolve over time into a cohesive, dynamic urban whole. His work, such as the Hillside Terrace in Daikanyama, developed over several decades, exemplifies a softer, more incremental approach to the Metabolist ideal of urban growth. Together, these architects and their peers wove a rich tapestry of ideas that expanded the possibilities of architecture.

The Paradoxical Beauty of Living Concrete

At the core of Metabolism’s aesthetic lies a captivating paradox: the use of starkly industrial concrete to convey fluid, biological ideas. This “organic concrete” imparts a distinctive and powerful character to the architecture, distinguishing it from the more monolithic Brutalist forms seen elsewhere around the globe.

Brutalism with a Biological Twist

Metabolism certainly shares a visual language with Brutalism. Both movements emphasize the honest expression of materials, especially béton brut—raw, unfinished concrete—and both reject superficial decoration in favor of revealing the underlying structure. However, their philosophical goals differ markedly. Western Brutalism often communicates a sense of permanence, massiveness, and fortress-like solidity. Consider the monumental housing estates of London or Boston’s imposing government buildings; they are heavy, grounded, and convey an image of unyielding authority. In contrast, Metabolist architecture employs concrete to suggest lightness, flexibility, and growth. While a Brutalist building may feel like a geological formation, a Metabolist one frequently resembles a biological organism. Here, concrete is not shaped into a singular, unified block but rather into a collection of distinct components—cores, branches, and cells. The aesthetic emphasizes aggregation and multiplication, as though the building were a crystalline formation or a coral reef, built up from countless smaller units. This essential contrast in intention—stasis versus dynamism—defines Metabolism as a unique progression of modernist ideals.

This organic sensibility is often heightened by the treatment of concrete surfaces themselves. The architects frequently left the texture of wooden formwork (sugiura) visible on the final surface. Although this technique is common in Brutalism, it takes on special meaning in the Japanese context. The faint grain of wood on the hard concrete creates a subtle tactile conversation between the industrial and the natural, a ghostly nod to the organic material that shaped the inorganic. It softens the material’s severity and adds a handcrafted warmth to these technologically bold structures.

The Cell, The Spine, The Branch: Biological Metaphors in Form

The shapes of Metabolist architecture directly reflect its fundamental philosophy, heavily drawing on biological imagery. The most prominent motif is the capsule or cell, the basic unit of life and, in Metabolism’s vision, of the city. The Nakagin Capsule Tower epitomizes this—a vertical cluster of individual living cells. This cellular approach suggested a democratic, non-hierarchical lifestyle, where each person occupied their own discrete, technologically-equipped space within the greater whole. The second key motif is the central core or spine. Seen in Tange’s Yamanashi Press Center and his student Arata Isozaki’s Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center, this element serves as the organism’s permanent trunk—robust and unchanging, providing stability and utilities so that transient parts may be attached. Finally, the branching, tree-like structures are evident in the large urban plans of Tange and Kikutake, where transportation networks and residential towers branch out from a central trunk, echoing the efficient, fractal logic of a tree reaching for sunlight. These metaphors were more than mere stylistic choices; they represented a sincere effort to create architecture whose very form embodied life’s principles: a stable core supporting adaptable edges, fostering continuous growth, change, and renewal over time.

A Pilgrimage to the Future That Was

While some of Metabolism’s most iconic structures have unfortunately disappeared, many significant examples remain, providing a tangible link to this era of remarkable optimism and innovation. Seeking them out is like embarking on an architectural pilgrimage—a journey toward a future envisioned half a century ago. The experience goes beyond merely admiring buildings; it involves grasping a profound chapter in Japanese cultural history.

Tokyo’s Metabolist Trail

Tokyo continues to be the epicenter of Metabolist thought, and although its presence has lessened, its spirit is still discernible throughout the sprawling metropolis.

Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center (Ginza)

Standing like an unusual, solitary tree among the glitzy, high-fashion surroundings of Ginza is Kenzo Tange’s Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center. This slender tower is a striking, accessible embodiment of the core-and-capsule concept. A single, massive cylindrical core—housing elevators and services—forms the trunk, from which cantilevered glass-and-steel office modules extend outward. The scene is one of dramatic contrast: the raw, brutal texture of the central concrete shaft sharply opposes the sleek, polished facades of the surrounding luxury boutiques. It feels like a relic from another era or realm, a functional sculpture placed in the heart of a commercial district. Access is straightforward; it’s a short walk from Shimbashi or Ginza stations. As a working office building, entry is restricted, but the exterior remains the main attraction. For first-time visitors, a great tip is to observe the building at different times: in bright daylight, the interplay of shadows highlights its powerful, sculptural form, while at dusk, as office lights glow, the modules appear as floating lanterns, giving the building an ethereal, otherworldly aura.

The Former Site of the Nakagin Capsule Tower (Shimbashi)

Visiting the site where the Nakagin Capsule Tower once stood offers a more reflective experience. Its demolition in 2022 marked a major loss for the architectural community, yet a visit to the now-empty lot in Shimbashi remains a meaningful pilgrimage. It presents an opportunity to contemplate the lifecycle of buildings and the challenges of preservation. Standing there, one can almost sense the ghost of the structure, its futuristic form etched into the city’s memory. This act of remembrance is, in a way, quintessentially Metabolist, acknowledging the impermanence even of the most iconic buildings. It’s also worth noting that the story continues beyond the rubble; several capsules were carefully removed and are being preserved and restored for display in museums and institutions throughout Japan and worldwide, including a prominent one at the Museum of Modern Art in Saitama. Though the tower itself is gone, its cellular DNA is dispersed, ensuring its legacy endures in a new, distributed form.

Beyond the Capital: Kofu and Kyoto

To fully appreciate the scope of the movement, one must venture beyond Tokyo.

Yamanashi Press and Broadcasting Center (Kofu)

A trip to Kofu city in Yamanashi Prefecture is essential for any dedicated student of Metabolism. Here, Kenzo Tange’s Yamanashi Press and Broadcasting Center stands as perhaps the most powerful and unadulterated expression of the Metabolist ideal still in use. A comfortable train ride from Tokyo, the building is just a short walk from Kofu Station. Its raw, muscular presence captures immediate attention. A cluster of sixteen service cylinders forms a dynamic, complex shape that shifts dramatically as you move around it. The building feels less designed and more grown—an inorganic forest of concrete. The atmosphere exudes immense strength and potential, perfectly conveying the idea of a durable, robust infrastructure poised to accept new additions. For photographers, the strong geometric shapes and the deep shadows they cast offer endless compositional opportunities. This is a structure that demands being experienced firsthand to fully appreciate its scale and conceptual clarity.

Kyoto International Conference Center

In Kyoto, a city renowned for its ancient temples and peaceful gardens, stands a monumental example of post-war modernism: the Kyoto International Conference Center. Designed by Sachio Otani, a key architect who worked under Kenzo Tange, it was completed in 1966. Though not a ‘capsule’ building in the Kurokawa style, it embodies the era’s spirit of grand scale, structural honesty, and bold geometric forms. Its most distinctive feature is its massive inverted trapezoidal structure, with exposed concrete beams creating a dramatic, almost crystalline framework. The building rests against the scenic backdrop of Lake Takaragaike and the surrounding hills, forming a striking dialogue between man-made and natural elements. Unlike many other Metabolist buildings, the public can often access the expansive, cathedral-like lobby and main halls. Walking through its cavernous interiors—with soaring ceilings and exposed concrete trusses—is an awe-inspiring experience, like stepping inside a giant, futuristic vessel. The center is easily reached via the Karasuma subway line, offering visitors a chance to experience the grand ambition of this architectural era from within.

Tips for the Architectural Pilgrim

When setting out to explore these sites, a few tips can enhance your experience. A wide-angle lens is invaluable since these buildings often emphasize overwhelming scale and geometric complexity. Try visiting at different times of day; shifting light can dramatically change the mood and texture of the raw concrete surfaces. Before your visit, spend some time reading about the design philosophy behind each building—understanding the architect’s intent will deepen your engagement beyond simple sightseeing. Lastly, remember many of these are active, working buildings; show respect for their occupants and explore with quiet appreciation.

Echoes in the Present, Lessons for the Future

The grand, unified vision of a Metabolist city, with its plug-in capsules and ever-expanding megastructures, never fully materialized. The dream faded when faced with the messy realities of economics, technology, and human nature. Yet, the echoes of Metabolism continue to resonate, and its core ideas feel more relevant today than ever before.

Why Did the Metabolist Future Fail to Fully Arrive?

The decline of Metabolism resulted from multiple factors. The oil crisis of the 1970s ended the era of rapid economic growth and boundless optimism that had driven such ambitious projects. The construction costs for these complex, unconventional structures were enormous. Moreover, the central concept of ‘plug-and-play’ architecture proved far more challenging in practice than in theory. As residents of the Nakagin Capsule Tower discovered, replacing a capsule was a complicated and prohibitively expensive process, requiring the removal of adjacent units and the use of massive cranes. The technological and logistical systems needed to sustain a truly metabolic city never fully developed. Socially, the world was also evolving. The ideal of the hyper-mobile, unencumbered individual living in a minimalist pod gave way to a renewed focus on community, stability, and the traditional family home. Critics further argued that the vast scale of Metabolist urban plans could feel inhuman, neglecting the need for intimate, human-scaled spaces and the chaotic, organic street life that enliven cities.

The Global Influence and Re-evaluation

Despite its unrealized promises, Metabolism’s impact was profound and widespread. Its ideas about exposed infrastructure and adaptable systems clearly influenced later movements, particularly the High-Tech architecture of architects such as Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, whose Centre Pompidou in Paris, with its external escalators and color-coded utilities, is a direct conceptual descendant. The movement also ignited the imaginations of architects worldwide, from the experimental Archigram group in the UK to countless others exploring prefabrication and modular construction. In recent years, there has been a notable resurgence of interest in Metabolism. In an era grappling with climate change, housing affordability crises, and the rise of remote work and digital nomads, Metabolist principles of flexibility, adaptability, and sustainability appear remarkably prescient. The concepts of prefabricated modular housing, multifunctional urban cores, and buildings designed for disassembly and reuse are all being revisited with renewed urgency. The passionate global debate surrounding the demolition of the Nakagin Capsule Tower stands as a testament to the lasting power of its vision. It sparked a critical conversation about which architectural heritage is worth preserving and what lessons we can draw from these bold experiments of the past.

The Enduring Concrete Poem

Exploring the surviving landmarks of Japanese Metabolism is more than merely observing old buildings. It involves engaging with a powerful concept: that cities can be living entities, designed not for a fixed, idealized future, but for the dynamic and unpredictable reality of human life. This movement emerged from a unique historical moment, blending post-war necessity, technological optimism, and a rich philosophical tradition. The ‘organic concrete vibe’ characterizing these structures is the tangible expression of this belief—a testament to the vision that even the most rigid and unyielding materials could be molded to embody growth, change, and rebirth. The capsules, cores, and megastructures that endure are not merely remnants of a past era. They serve as prompts, urging us to envision our own urban futures with greater creativity and flexibility. They stand as a beautiful, lasting concrete poem, written in a language of hope, celebrating the endless, metabolic cycle of life itself.