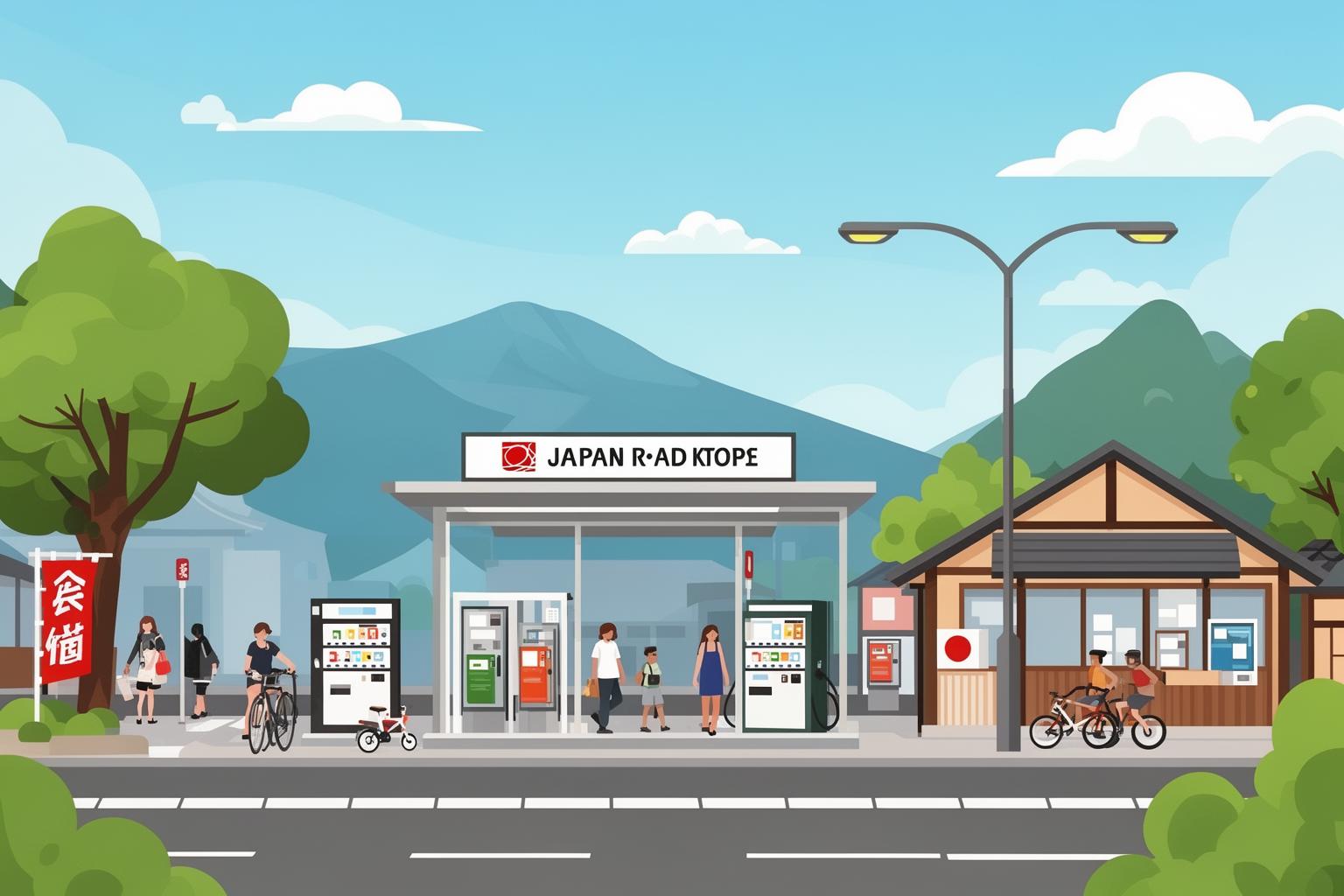

Okay, let’s get real for a second. You’re on a road trip in Japan, cruising through epic mountain passes or hugging a dramatic coastline. You’ve seen the photos, you know the vibe. Then you see a sign for a “Michi no Eki,” a roadside station. You pull in, expecting… what, exactly? A slightly cleaner version of a highway service center? A place to grab a lukewarm coffee and a sad-looking sandwich? That’s the logical assumption, based on pretty much anywhere else in the world. But what you find instead is a sprawling concrete building that looks like a minimalist community hall, a farmers’ market bursting with vegetables you’ve never seen before, and a line of local grandpas and grandmas sipping tea like it’s their own personal clubhouse. You see families letting their kids run wild in a pristine playground, a restaurant serving some hyper-local noodle dish that isn’t on any tourist menu, and toilets so advanced they could probably file your taxes. You look at the stark, functional architecture and the vibrant, hyperlocal life buzzing within it, and you think, “What is this place? And why does it feel so… important?”

That confusion is completely valid. Because a Michi no Eki isn’t just a place to stop; it’s a destination. It’s a solution to a dozen different Japanese social and economic problems, all cleverly disguised as a place to use the bathroom. These ‘Concrete Oases’ are a physical manifestation of modern Japan’s priorities: community, safety, hyper-local pride, and an almost obsessive commitment to practical, multi-purpose design. They are the absolute opposite of a soulless corporate chain. They are a government-sponsored, locally-run network of community hubs that are, low-key, one of the most brilliant and uniquely Japanese concepts you’ll encounter. To understand the Michi no Eki is to understand how Japan tackles rural decline, prepares for disaster, and celebrates its culture, one perfectly polished daikon radish at a time. It’s a whole system, a philosophy built from concrete and community spirit. So, let’s break down why these roadside stations are so much more than meets the eye, and why their often-brutalist architecture is actually a key part of the story.

This commitment to concrete as a medium for profound experience is also explored in our look at Tadao Ando’s spiritual use of concrete.

The ‘Why’ Behind the Concrete: Deconstructing the Michi no Eki Concept

To truly understand why Michi no Eki exist, you need to go back to the early 1990s. Japan was undergoing a major cultural shift. The country was emerging from the extravagant, money-driven 1980s Bubble Economy. The aftermath was harsh, especially for rural areas. For decades, Japan’s story had been one of centralization. The brightest and most talented young people left their small towns and villages in search of education and high-paying jobs in megacities like Tokyo and Osaka. This depopulation trend, known as kasoka (過疎化), was devastating the countryside. Local economies based on farming, forestry, or fishing were contracting. Schools were shutting down. The population was aging rapidly, leaving communities made up mostly of elderly residents.

At the same time, a new trend was developing. As the country grew wealthier, car ownership skyrocketed. People weren’t just commuting; they were driving for pleasure. A new culture of leisure driving and domestic tourism was taking root. Families and couples spent their weekends driving to explore the very countryside struggling to survive. They sought authentic experiences, scenic routes, and a taste of rural life. This created a classic supply-and-demand dilemma. There was a surge of new drivers on roads, but the infrastructure was lagging. There was a real need for safe, clean, and dependable rest areas, especially on long rural journeys. You couldn’t simply pull over on the edge of a narrow mountain road.

This is where the Japanese government stepped in, specifically the Ministry of Construction (now the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, or MLIT). They recognized these two intersecting trends—rural decline and the rise of car culture—and devised an ingenious solution. What if both problems could be addressed through a single piece of public infrastructure? What if a rest stop could offer more than just a toilet and vending machines? What if it could serve as a tool for chiiki shinkō (地域振興), meaning regional promotion and revitalization? This idea sparked the creation of the Michi no Eki system in 1993.

The government established clear core principles. To be officially designated as a Michi no Eki, a facility had to fulfill three essential functions, which is where things get interesting. First, the Rest Function: free, 24-hour parking and, most importantly, impeccably clean, 24/7 public restrooms. This isn’t merely a convenience; it’s a non-negotiable standard reflecting Japan’s profound cultural focus on public hygiene and safety. Second, the Information Function: each station must offer up-to-date information on road conditions, traffic, weather, and local travel guidance. Additionally, these stations play a critical role as disaster information hubs for travelers and residents, essential in a country prone to earthquakes and typhoons. This dual role as both tourist convenience and community lifeline is a key theme.

Finally, and the true game-changer, is the Regional Promotion Function. This is the heart and essence of Michi no Eki. The government required these stations to actively collaborate with local communities to showcase and sell regional products, promote tourism, and serve as gathering spaces for locals and visitors. This is not optional; it’s the central mission. Suddenly, a simple roadside stop took on the responsibility of revitalizing its town. It became a direct marketplace for local farmers, a gallery for artisans, a restaurant for regional cuisine, and a venue for community events. Designed from the ground up, it functions as an economic engine, a cultural ambassador, and a community hub, all conveniently located just off main roads. This foundational concept distinguishes Michi no Eki from any other rest stop worldwide and explains why entering one feels like stepping into the true heart of a region.

Architecture as a Statement: Utilitarianism Meets Local Identity

So, we’ve clarified the why. Now, what about the what? Let’s focus on the buildings themselves. When you encounter your first few Michi no Eki, especially the older ones from the ’90s and early 2000s, a distinct aesthetic becomes apparent. That aesthetic can often be summed up in one word: concrete. Lots and lots of concrete. The designs are typically stark, functional, and utilitarian, sometimes verging on brutalist. They might resemble a municipal water treatment plant or a small-town city hall more than a quaint country market. This is intentional. The architectural decisions are as purposeful and telling as the services provided inside.

The frequent use of concrete and functionalist design arises from a few uniquely Japanese factors. First and foremost is pragmatism and durability. Japan constantly contends with the forces of nature. It’s a land prone to powerful earthquakes, raging typhoons, heavy rains, and, in many areas, heavy winter snowfall. Public infrastructure must be resilient. It must endure. Concrete is a straightforward and effective material suited to this environment. It’s strong, low-maintenance, and resistant to both fire and water. This architecture isn’t meant to be fragile or fanciful; it’s designed to withstand a magnitude 7 earthquake. This focus on robustness is a fundamental principle of Japanese civil engineering and public development.

Second, there was the economic reality following the Bubble era. The extravagant, no-expense-spared architectural statements of the 1980s had ended. The 1990s, often termed the “Lost Decade,” brought an age of austerity and practicality. Public projects had to deliver the best value for money. The emphasis shifted to function over form, catering to the community’s needs without unnecessary expense. The simple, box-shaped concrete buildings were economical to construct and maintain. The beauty wasn’t intended to lie in the building itself, but in what the building enabled. The structure acted as a blank canvas, a neutral frame designed to highlight the local community’s vibrant colors—the bright red tomatoes, the green spinach, the colorful handmade crafts, and the lively crowds. In a distinctly Japanese manner, the container humbly recedes to allow the contents to shine. The building’s role is to serve, not to show off.

Beyond the Box: Architects Embrace Creativity

But that’s only part of the tale. As the Michi no Eki concept grew and demonstrated success, its architectural style began evolving. While the basic principles of functionality and community focus stayed intact, newer stations or renovated older ones have become architectural landmarks in their own right. Design started to be used not just as a container, but as an active tool for regional promotion, narrating the story of the place through the building’s materials and shapes.

A prime example of this progression is Michi no Eki Mashiko in Tochigi Prefecture. Mashiko is renowned across Japan for its distinctive pottery style, Mashiko-yaki. It’s an artisan community, a ceramics hub. The former roadside station was a fairly typical, uninspired structure. The new one, opened in 2016, directly reflects the town’s identity. The design incorporates natural wood, earthy tones, and sloped roofs reminiscent of the traditional kilns used by potters. The interiors are open and gallery-like, intended to beautifully showcase not only local produce but also local ceramic artworks. The building feels crafted, handmade, and deeply tied to the local artistic legacy. It doesn’t just promote Mashiko’s culture; it embodies it.

Then there are the true architectural showpieces, such as Michi no Eki Tomika in Gifu Prefecture, designed by the internationally acclaimed architect Kengo Kuma. This isn’t merely a structure; it’s a striking statement. Gifu is famous for its high-quality hinoki (Japanese cypress) wood and a long lineage of master carpentry. Kuma’s design for Tomika uses massive, interlocking beams of local wood to create a soaring, forest-like canopy that is both modern and deeply traditional. It highlights the region’s key resource and its treasured craftsmanship in an unforgettable way. Approaching it, you are immediately told a story about Gifu’s identity. It proves that purely utilitarian public infrastructure can also be fine art, and that the building itself can be the most powerful form of regional promotion.

Even stations maintaining a modernist concrete style do so with great intent. Consider Michi no Eki Nanbu in Yamanashi Prefecture, the one shown on the map. It’s a sleek, contemporary building featuring sharp angles and large glass panels. But the design is far from arbitrary. It’s situated to provide panoramic views of the Fuji River and the surrounding mountains. The architecture is crafted to frame the natural scenery, connecting visitors indoors with the outdoors. The concrete and glass don’t aim to steal the spotlight; they exist to facilitate a bond with the region’s stunning landscape. In every instance, the architecture—whether modest or grand—is a purposeful choice supporting the station’s ultimate goal: to celebrate and sustain the local community.

The Genius of the Layout: A Typical Michi no Eki Tour

Beyond the building’s exterior, the interior layout of a Michi no Eki exemplifies user-focused, community-centered design. There’s a predictable yet ingenious flow that guides you through the story of the region. Let’s take a typical tour.

You park in the spacious, always-free lot. The first thing you’ll almost certainly encounter is the vibrant heart of the operation: the farmers’ market, or chokubaisho (直売所), literally “direct sales place.” This isn’t the curated, picture-perfect market you might find in a trendy Western city. It’s raw, authentic, and wonderfully genuine. The produce is often piled high in simple plastic crates or woven baskets. You’ll spot muddy daikon radishes, slightly misshapen cucumbers, and bundles of leafy greens, likely harvested just a few hours earlier. The focus is on freshness and seasonality, or shun (旬)—a key concept in Japanese cuisine. You find only what’s in season right now, in this specific locale. It’s a direct connection to the local agricultural rhythm.

What truly sets the chokubaisho apart is its personality. Each item is individually priced and packed by the farmer who grew it. Often, you’ll find a small label with the farmer’s name, sometimes even a smiling photo and a handwritten note like, “I grew these tomatoes with love. They are extra sweet this year!” This fosters a deep sense of connection and trust between producer and consumer. This isn’t anonymous produce from a vast supply chain; it’s Tanaka-san’s spinach and Suzuki-san’s shiitake mushrooms. It’s a system founded on local reputation and pride.

Next, you’ll head to the restaurant or cafeteria. Forget any preconceived ideas about bad highway food. The menu here is a culinary embassy for the town. If the area is known for soba noodles, you’ll find handmade soba made from locally milled buckwheat. If the nearby coast is famous for a certain fish, that’s what appears in the grilled fish set meal. Often, there’s a “soft cream” (soft-serve ice cream) stand offering unique local flavors you won’t find anywhere else—wasabi, sweet potato, purple yam, or even miso. Dining at a Michi no Eki is one of the best and most affordable ways to enjoy authentic, unpretentious regional cuisine.

Nearby, you’ll find the information corner. This space underscores the station’s public utility. Alongside pamphlets for local sites, the key feature is usually a set of large digital screens showing real-time road conditions from MLIT cameras. They indicate construction ahead, mountain passes closed due to snow, or heavy rain in the next valley. It’s a practical, vital service for drivers navigating rural roads they might be unfamiliar with. And, of course, in emergencies, this spot becomes where crucial disaster updates are broadcast.

Lastly, there are the toilets. It may seem cliché to mention Japanese toilets, but at a Michi no Eki, they form a vital part of the experience and philosophy. They are universally, without exception, spotlessly clean. They are free, safe, and open 24/7. Even at the most remote mountain stations, you’ll often find high-tech toilets with heated seats, multiple bidet functions, and sometimes a sound-masking “privacy” button. This isn’t a luxury; in Japan, it’s the baseline standard for public facilities. It reflects a societal commitment to public comfort, hygiene, and dignity. Being able to rely on such quality anywhere in the country is key to making road trips in Japan stress-free. The toilets aren’t an afterthought; they’re a fundamental pillar of the Michi no Eki promise of a safe, comfortable rest.

More Than a Market: The Michi no Eki as a Community Hub

If you regard a Michi no Eki merely as a convenient rest stop for tourists, you’re overlooking its broader significance. Its most important role is often serving as a vital community hub for the local residents themselves. Here, the practical architecture transforms into a refuge—not just for travelers, but for the people who live there year-round. In many of Japan’s depopulating rural regions, the Michi no Eki has effectively become the town square, the social center of communities that may have lost their local shops, post offices, or community centers.

For many elderly locals, visiting the Michi no Eki is a daily or weekly routine. It offers them a reason to leave their homes. They come to sell vegetables grown in their own gardens, providing a modest but meaningful source of income and a sense of purpose. More importantly, they come to connect with others. Groups of grandparents can often be found gathered on benches, chatting over tea or shared snacks. It’s their ibasho—a Japanese term roughly meaning “a place where one can feel comfortable and be themselves.” In an aging society where social isolation is a serious issue, these stations offer a vital space for connection and belonging. Their mere presence helps combat loneliness.

Economically, the Michi no Eki is a crucial lifeline. It offers a straightforward, low-barrier sales outlet for small-scale producers who would otherwise be excluded from mainstream agricultural distribution networks. A farmer with a small plot cannot compete with large agricultural cooperatives, but they can package and sell their own produce at the local Michi no Eki, retaining full pride and a much higher share of the profits. This system helps preserve local heirloom vegetable varieties, traditional food-processing methods (like pickling and miso-making), and craft skills that might otherwise disappear. It empowers communities to leverage their unique culture, turning it into a sustainable economic resource.

Perhaps the most vital yet least visible function of a Michi no Eki is its role as a bōsai kyoten (防災拠点), or a designated disaster prevention base. This aspect is a game-changer and sheds light on much of their design. Many of these seemingly over-engineered concrete structures are built to endure severe natural disasters. Their large, open parking areas are designed to accommodate emergency vehicles, temporary shelters, and even helicopter landings. They often feature backup power generators, emergency food and water supplies, and disaster-relief toilets. The 24/7 information services become a critical command-and-control communications hub during emergencies.

Following major earthquakes such as those in Tohoku in 2011 or Kumamoto in 2016, Michi no Eki proved invaluable. They functioned as safe evacuation sites, distribution centers for relief supplies, and staging points for first responders. This intentional, dual-use design exemplifies Japanese societal preparedness. Everyday infrastructure is constructed with worst-case scenarios in mind. So when you see a Michi no Eki and think, “This seems overbuilt for a farmers’ market,” you’re correct. It’s much more than just a market. It’s a fortress, a shelter, a community lifeboat, patiently waiting for a storm everyone hopes never arrives. The concrete isn’t just for durability or aesthetics; it’s a promise of safety.

The Vibe Check: Is a Michi no Eki Stop ‘Worth It’?

Alright, we’ve established that Michi no Eki are a fascinating, multi-dimensional social phenomenon. But let’s get down to the essentials. You’re on a tight vacation schedule. You’ve got a Japan Rail Pass to make the most of and a list of temples and shrines to visit. Is it really worth your time to stop and explore one of these spots? The honest answer is: it depends on what you’re seeking. It calls for a slight shift in your typical tourist mindset.

If you’re expecting a polished, theme-park-style version of “Rural Japan,” you might be let down. A Michi no Eki isn’t a show. It’s a living, functioning part of the community. Its appeal lies in its authenticity, not its polish. The lighting may be a bit fluorescent, the displays might be straightforward, and the highlight could genuinely be a huge, perfectly formed winter melon. It’s a glimpse into real, unpretentious, everyday life. If you approach it with curiosity and an open mind, it can turn out to be one of the most rewarding and memorable stops on your journey. But if you’re after slick branding and Instagram-worthy aesthetics, you might find it somewhat plain.

Who is it for?

So, who truly benefits from the Michi no Eki experience? First, The Road Tripper. If you’ve rented a car to explore Japan—an absolutely fantastic way to see the country—then Michi no Eki aren’t just worthwhile; they’re essential. They are your lifelines. They offer the cleanest restrooms, the most reliable information, and excellent-value local meals. They serve as perfect break points during a day of driving, letting you stretch your legs, refuel, and get a genuine taste of the region you’re passing through.

Second, The Foodie. If you have even a passing interest in Japanese cuisine beyond sushi and ramen, a Michi no Eki is a real treasure chest. It’s a direct gateway to the country’s incredible regional biodiversity. You’ll find mountain vegetables (sansai) you’ve never encountered, dozens of varieties of local pickles (tsukemono), handmade miso paste, and fruits and vegetables that taste remarkably better than anything in city supermarkets. It’s the ideal place to buy edible souvenirs that truly represent your travels. I once bought a jar of yuzu-miso at a tiny Michi no Eki in Shikoku that I still dream about—it’s a flavor I’ve never found elsewhere, made by someone from that very valley.

Third, The Cultural Explorer. If your aim is to understand how Japan really functions, a stop at a Michi no Eki can be more enlightening than many museums. Here you witness the social contract in action. You see the direct link between producers and consumers. You observe how a community cares for its elderly members. You sense the deep pride people take in their local specialties, no matter how modest. On a family trip through the Japan Alps, we stopped at a station in a village known for its apples. An elderly farmer had set up a simple apple press and was selling fresh-pressed juice. He didn’t speak English, and we spoke little Japanese, but through smiles and gestures, he showed my kids how the press worked and let them taste the juice. It was a brief, five-minute exchange that conveyed the pride and warmth of that community. It was genuine.

What it’s not.

To manage expectations, it’s also important to know what a Michi no Eki isn’t. It’s generally not a polished tourist trap. The souvenirs are more likely to be bags of dried mushrooms or bottles of local soy sauce rather than mass-produced keychains. English signage and explanations can be inconsistent. This imperfection is part of its charm—it hasn’t been overly commercialized for foreign visitors. It calls for a bit of adventurous spirit. If you’re not interested in the subtleties of regional Japanese agriculture, its appeal may be limited. But if you’re willing to venture slightly off the beaten path and engage with the real Japan, these places are an absolute treasure trove.

The Future of the Concrete Oasis

Like everything in Japan, the Michi no Eki concept is continuously evolving. It adapts to the changing needs of both travelers and local communities. The core formula of rest, information, and promotion has been so successful that it is now being enhanced in creative and exciting ways. The future of these concrete oases points toward greater specialization and experience-based offerings.

A trend is emerging toward Michi no Eki with a unique, focused theme. Some stations now feature an onsen (natural hot spring), allowing tired drivers to relax before continuing their journey. Others have added craft breweries, wineries, or sake distilleries, providing tastings and tours that highlight local beverage production. Some stations include large dog parks to accommodate the rising number of travelers with pets, while others have introduced campgrounds or glamping sites, transforming the rest stop into an overnight destination. One especially famous station, Den-en Plaza Kawaba in Gunma, has grown into a major attraction, with a hotel, several restaurants, a brewery, and artisan food shops, drawing millions of visitors annually. It serves as a model for what a highly successful, diversified Michi no Eki can become.

There is also a strong movement toward the “experience economy.” It’s no longer just about selling products but providing memorable activities. Numerous stations now host hands-on workshops where visitors can learn to make soba noodles, try pottery, or master a local craft. Others are linked to nearby farms offering fruit-picking experiences—strawberries in spring and grapes in fall. These activities deepen visitors’ connections to the region and give them a compelling reason to stay longer and spend more.

Of course, challenges remain. The very issue the stations were designed to address—the aging and shrinking rural population—also impacts the Michi no Eki themselves. Recruiting enough local farmers to supply markets and staff to manage the facilities can be difficult. They also compete with the highly efficient and ubiquitous Japanese convenience stores (konbini), which are now commonly found even along rural highways.

Despite these obstacles, Michi no Eki remains one of the most successful and fascinating examples of modern Japanese public policy. What began as a simple idea to offer safe rest areas for drivers has grown into a nationwide network of over 1,200 unique, vibrant community hubs. They represent a different way of thinking about infrastructure—not just as a means to move people and goods, but as a way to support communities, preserve culture, and foster resilience.

So the next time you’re driving through the Japanese countryside and see that sign, don’t view it merely as a rest stop. See it as a microcosm of modern Japan. See the stark, practical concrete as a symbol of safety and endurance. See the rows of fresh vegetables as a tale of local pride and economic survival. And see the group of local grandmas sharing laughter over tea as a testament to the lasting power of community. Pull over. Step inside. Buy a peculiar-looking pickle or an extraordinarily sweet piece of fruit. You’ll be doing more than just taking a break; you’ll be taking part in a quiet, brilliant revolution happening every day, in concrete oases all across Japan.