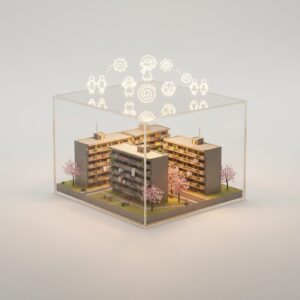

Yo, what’s the deal? Shun Ogawa here. So you’ve been scrolling through the infinite feed, maybe deep in a late-night anime binge or planning a trip, and you keep seeing them. These massive, monolithic concrete apartment blocks. They’re everywhere, flanking train lines, dominating suburban skylines, looking like something straight out of a dystopian sci-fi flick. They stand in such stark, almost aggressive contrast to the serene temples and neon-drenched cityscapes that define Japan in the global imagination. You’re probably thinking, “Okay, what’s the story here? Is this just… what normal life looks like? Why does it look so… bleak?” It’s a legit question. These buildings, known as danchi (literally “group land”), are not just random concrete jungles. They are a living, breathing, and sometimes crumbling, archive of Japan’s post-war soul. They tell a story of total devastation, explosive ambition, a dream of a new middle class, and the quiet, complicated reality that followed. Forget what you think you know. We’re about to decode the Brutalist beauty and the reimagined communities of Japan’s concrete danchi, and trust me, it’s a whole mood. It’s the history lesson you never got in school, served up with a side of architectural realness. To get a sense of the sheer scale we’re talking about, peep this mega-danchi in Tokyo. It’s a whole city within a city.

このダンチのブルータリズムの美学をさらに深く知りたいなら、Tadao Andoのコンクリート建築が提供する瞑想的な空間もチェックしてみよう。

The Ghost in the Machine: Post-War Japan’s Housing Sitch Was Dire AF

To understand why danchi exist, you have to rewind to 1945. Japan was, to put it mildly, utterly devastated. Major cities like Tokyo and Osaka were reduced to ash-covered ruins. Firebombings had destroyed millions of homes, resulting in a housing shortage that was staggering—about 4.2 million units short. People were living in makeshift shacks, burnt-out building shells, or anything they could find. The entire nation was in survival mode. So, when post-war recovery began and the economy started its remarkable rise, the government faced a huge problem. You can’t build a new economic powerhouse if your workforce is living in poor conditions. The housing crisis was a national emergency, a bottleneck choking the country’s potential.

The government’s solution was bold and extremely practical. In 1955, they created the Japan Housing Corporation (JHC), now called the Urban Renaissance Agency or UR. Its mission was straightforward but monumental: to build a vast number of affordable, modern, fireproof, and earthquake-resistant homes for the growing population of salaried workers—the “salarymen” who would drive Japan’s economic miracle. This wasn’t about style; it was about logistics. It required a wartime level of mobilization focused on construction. They needed a model that was quick to build, scalable, and cost-effective. The answer was reinforced concrete. The answer was the danchi. These weren’t just buildings; they were the foundation for the framework of a new Japan. They physically embodied a national effort to create a stable, healthy, and productive middle class from the literal ashes of defeat. The stark, uniform look wasn’t a design choice; it was the unavoidable outcome of a desperate race against time and a radical vision for a new society.

Birth of a Concrete Utopia: The Danchi Dream Was the Original Flex

It’s kind of wild to think about now, but in the 1950s and 60s, securing a spot in a danchi was like hitting the lottery. Really. Demand was so intense that actual lotteries were held to allocate apartments, with application rates sometimes reaching as high as 100 to 1. Moving into a danchi was a major status symbol, the ultimate flex for a young family—it meant you had truly arrived and were part of the new, modern Japan.

Why? Because danchi offered a lifestyle that was downright futuristic for the era. Before danchi, most people lived in traditional wooden houses with tatami rooms, shared toilets, and kitchens that were often dark, smoky afterthoughts. Danchi introduced a revolutionary idea to the masses: the “LDK” layout—Living, Dining, and Kitchen. This concept of distinct spaces for different family activities was a game-changer. The kitchen was no longer a hidden utility room; it became the bright, functional heart of the home. Danchi kitchens often featured what were then considered incredible luxuries: a stainless steel sink, a gas stove, and running water. This was called the “cultural kitchen,” designed as a space for the modern housewife.

But the innovation didn’t stop there. These apartments had private, Western-style flush toilets and balconies for drying laundry in the sun. The concrete construction made them safer from the fires and earthquakes that frequently devastated traditional wooden neighborhoods. Living in a danchi was a complete lifestyle shift, representing a break from the past and an embrace of a Western-inspired, scientific, and rational way of living. The complexes themselves were planned as self-contained utopias, complete with parks, playgrounds, clinics, post offices, and shopping arcades on site. It was a vision of clean, safe, and convenient living—a sharp contrast to the chaotic and often unsanitary conditions of the immediate post-war years. For the first generation of danchi residents, these concrete blocks weren’t ugly or oppressive; they were shining symbols of peace, prosperity, and a bright future for their children—the Japanese Dream, brought to life in concrete.

The Brutalist Vibe Check: An Accidental Aesthetic

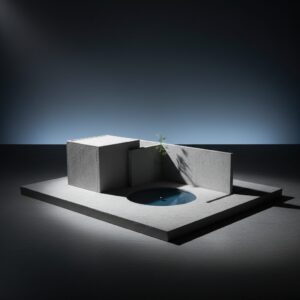

The architectural style of the danchi is unmistakably Brutalist. We’re talking raw, exposed concrete (béton brut, as Le Corbusier—the godfather of the movement—called it), repetitive geometric forms, and a monumental scale that can feel both imposing and awe-inspiring. But here’s the twist: Japan didn’t intend to become a Brutalist architecture haven. The choice was almost entirely pragmatic. Concrete was the ideal material for the mission: durable, fireproof, earthquake-resistant, and relatively cheap and easy to mass-produce. The focus was on function, speed, and standardization—not on winning design awards.

This function-over-form philosophy is the essence of Brutalism. The style is honest. It doesn’t conceal its construction. The raw concrete surfaces reveal the texture of the wooden molds they were cast in. The structure itself is the aesthetic. There’s no ornamentation, no pretense. It’s a building that declares, “I am made of concrete, and my purpose is to shelter you efficiently.” This accidental embrace of Brutalism created a distinctive visual language across Japan. While Western Brutalism was often linked to government buildings and university campuses—symbols of state power—Japanese Brutalism, through the danchi, became the architecture of the people, the everyday backdrop for millions.

Over the decades, this aesthetic has taken on a life of its own. The concrete, once a clean gray, has weathered and aged, stained by rain and time, creating a wabi-sabi effect of imperfect beauty that was never intended. These buildings have become powerful visual icons of the Showa Era (1926–1989). Deeply embedded in cultural consciousness, they are staple settings in anime, manga, and films, often evoking nostalgia, melancholy, or the quiet dramas of working-class life. What began as a purely utilitarian solution has, through time and cultural assimilation, become an iconic and unexpectedly beautiful part of the Japanese landscape.

The Dream Fades: From Aspiration to Isolation

Nothing lasts forever, and the golden era of the danchi was no exception. By the 1980s, the dream was beginning to show significant cracks. The very economic miracle that the danchi had helped create brought about a new level of affluence. The middle-class dream had evolved. The new aspiration was no longer a compact apartment in a concrete block; it was a single-family home with a garden in the suburbs, a ikkodate. Families who could afford it started moving out, seeking more space and the prestige associated with land ownership.

As the original residents aged and their children moved away, the demographics of the danchi shifted dramatically. These once lively communities, filled with the sounds of children playing, became quiet. They turned into homes for a rapidly aging population. This shift led to numerous serious social problems. The buildings, designed for the nuclear families of the 1960s, were ill-suited to the needs of the elderly. Walk-up buildings without elevators became traps for residents with mobility challenges. The uniform, maze-like layouts, once a hallmark of rational planning, became confusing for older individuals.

Here, a darker aspect of the danchi story unfolds, exemplified by the phenomenon of kodokushi, or “lonely deaths.” With elderly residents living alone, isolated from family and community, it became increasingly common for people to die in their apartments and remain undiscovered for days, weeks, or even months. Danchi, once symbols of community and connection, ironically turned into centers of deep social isolation. The concrete utopia had, for many, become a concrete prison. The buildings began to look outdated, amenities lagged behind modern standards, and a stigma grew around danchi life. They were no longer seen as desirable stepping stones but as housing of last resort—a place where people ended up, not where they aspired to live. The vibe was no longer bussin’.

The Danchi Renaissance: It’s Giving Second Life

Just when it seemed like the danchi were destined to fade into irrelevance, something unexpected happened. A new generation began to view these concrete giants with fresh appreciation. A renaissance unfolded, fueled by a perfect combination of shifting values, smart design, and economic necessity. Young people in Japan, grappling with stagnant wages and the exorbitant cost of new housing, started to recognize the potential in these old, sturdy, and often well-situated apartment blocks. The danchi revival was underway, and it has been a complete transformation.

The MUJI x UR Collaboration: A Minimalist Transformation

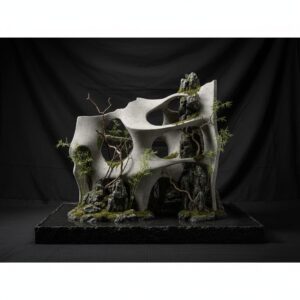

One of the most prominent and influential forces in this revival is the collaboration between MUJI, the brand known for Japanese minimalist design, and UR, the very agency that originally built the danchi. This partnership is pure brilliance. MUJI and UR take old, worn danchi units and give them a radical refresh. But it’s not about adding flashy new elements; it’s about peeling them back to their essential core. They frequently remove interior walls to create open, adaptable spaces. They strip away dated fixtures and finishes, exposing the raw concrete structure and wooden beams. They install simple, high-quality kitchens and bathrooms, leaving the rest as a blank canvas for residents to make their own.

The result is apartments that are bright, airy, and perfectly aligned with modern aesthetics. They celebrate the building’s history rather than hiding it. This approach turned the danchi’s perceived flaws—its age and raw materials—into its greatest assets. Suddenly, living in a danchi wasn’t just affordable; it was stylish. It was a deliberate aesthetic choice, rejecting the disposable consumerism of cookie-cutter new developments. The MUJI x UR project demonstrated that these old concrete shells had strong foundations and, with a bit of creativity, could be transformed into highly sought-after homes for a new generation of creatives, young families, and design-conscious individuals.

Community Takes Center Stage Again

This renaissance isn’t just about interior design; it’s a comprehensive effort to resurrect the original utopian vision of the danchi as a community hub. Recognizing that social isolation was the biggest failing of aging danchi, UR and various non-profits are now investing resources into rebuilding the social fabric. Here’s where the story gets really compelling. They are actively working to curate a more diverse mix of residents, offering incentives to attract young families and students to balance an aging population.

They are reimagining the underutilized common spaces that are scattered throughout each danchi complex. Vacant ground-floor apartments are being converted into co-working spaces, childcare centers, community cafés, and workshops. Open green areas are becoming community gardens and urban farms where residents can cultivate food together. Flea markets, seasonal festivals (matsuri), and educational workshops are organized to encourage residents to leave their apartments and interact with neighbors. The goal is to make the danchi a “main character” in residents’ lives again, not just a passive backdrop. It’s a deliberate effort to combat loneliness and foster a sense of shared ownership and belonging. This new approach acknowledges that a thriving community needs more than just well-designed buildings; it requires social infrastructure, shared activities, and reasons for people to connect. It’s a return to the danchi’s founding ideal, updated to meet 21st-century challenges and desires.

Art & The Concrete Canvas

The cultural reevaluation of the danchi has also found expression through art. The stark, repetitive facades of these buildings have become a vast canvas for artists and a source of creative inspiration. In certain complexes, large-scale murals break up the monotony of concrete and add playfulness and identity to the neighborhood. Art projects involving residents, especially children, foster a sense of pride and connection to their surroundings.

Beyond formal art installations, a whole subculture has developed online romanticizing the danchi aesthetic, sometimes called danchi-moe. Photographers are drawn to the bold geometry, melancholic mood, and textures of the aging concrete. Illustrators and animators continue to use the danchi as a powerful backdrop for stories about modern Japanese life. This artistic and cultural embrace has helped reshape public perception of danchi. No longer merely symbols of decay or poverty, they are now seen as sites of historical significance, architectural interest, and retro-chic nostalgia. In a way, they have become fashionable. This cultural cachet only adds to the appeal of living in a renovated danchi, turning a housing choice into a statement of cultural awareness.

So, Why Does It Still Feel… Different? The Danchi Reality Check

Alright, so we’ve discussed the glow-up, the MUJI collaborations, and the community revival. It all sounds pretty incredible, doesn’t it? But let’s be honest. If you visit a danchi complex tomorrow, it won’t be all artisanal coffee shops and minimalist dream apartments. The reality on the ground is far more complicated and uneven. The renaissance is genuine, but it’s not universal.

For every stylish, renovated danchi featured in a design magazine, there are dozens that haven’t been touched since the 1970s. In these complexes, the challenges of an aging population and deteriorating infrastructure remain very much alive. You’ll encounter hallways with peeling paint, overgrown public spaces, and shuttered shops in the local arcade. The social isolation that leads to kodokushi hasn’t vanished miraculously. These are deep-rooted societal issues that a fresh coat of paint and a community garden alone can’t resolve.

The renovation efforts themselves, while impressive, are limited in scope. They often serve as pilot programs or focus on specific, desirable areas. The cost of renovating millions of aging units nationwide is staggering, and the bureaucracy of a large organization like UR moves slowly. Moreover, there’s a delicate social balance to maintain. While attracting younger residents is crucial for revitalization, it can also cause tension with long-term elderly residents who may be resistant to change or feel their peaceful lifestyle is being disrupted. The “danchi dream” is being rebooted, but it’s a system update still downloading, full of bugs and compatibility issues. Understanding danchi means embracing this duality: it is both a place of exciting renewal and ongoing decay, a symbol of hope and a reminder of entrenched social challenges.

The Final Take: Japan’s Concrete Soul

So, when you gaze at those endless concrete blocks from the train window, what are you truly seeing? It’s not just cheap housing. You’re witnessing a physical timeline of Japan’s entire post-war history. These buildings stand as monuments to a nation’s desperate, ambitious, and remarkably successful race to recover from total devastation. They are the cradle of the modern Japanese middle class, where the dream of a comfortable, consumer-driven life was born for millions.

They also bear silent witness to the quiet heartbreak of that dream aging, fraying at the edges, and yielding to the unrelenting forces of demographic shifts and economic stagnation. Now, in their third chapter, they are transforming into a canvas for a new generation’s effort to redefine what community, home, and a good life mean in a radically changed Japan. They wrestle with questions of sustainability, social connection, and honoring the past while shaping the future.

To understand the danchi is to grasp the very essence of modern Japan. It means recognizing that behind the polished veneer of high-tech cities and ancient traditions lies a story of radical pragmatism, large-scale social engineering, dreams both made and lost, and the ongoing, quiet struggle to adapt and find meaning. The danchi are not an anomaly; they represent one of the most genuine, honest reflections of the country’s journey. They are raw, intricate, and undeniably, Japan. And now, you understand.