Yo, what’s the deal with those massive, same-y apartment blocks you see all over Japan? Peep this scene: endless grids of concrete, identical balconies stretching out to the horizon, maybe a water tower standing guard like a retro-futuristic robot. You’ve definitely seen them in a lo-fi anime edit, a gritty yakuza flick, or in the background of a thousand street photos. These are Japan’s danchi, and they’re way more than just old-school housing. They’re low-key the architectural backbone of modern Japan, a whole vibe that’s equal parts nostalgic, utopian, and kinda melancholic. It’s a concrete jungle, for real, but one that holds the collective dreams of an entire generation. But like, why are there so many? And why do they all look the same? It’s a story about a country pulling itself out of the ashes, chasing a new kind of life, and building that dream one prefabricated panel at a time. It’s a wild ride from post-war desperation to retro-chic revival. Let’s get into it, and decode the soul of these concrete giants.

To see how this concrete aesthetic evolved into other forms of modern architecture, explore Japan’s most hyped sci-fi bunker hotels.

The Birth of the Concrete Dream: Post-War Japan’s Housing Crisis

To truly understand the danchi, you need to rewind time to post-World War II Japan. The major cities, particularly Tokyo and Osaka, were essentially devastation zones. Firebombing had destroyed millions of homes, leaving people living in makeshift shacks, burnt-out building shells, or anything they could find. The housing shortage was not merely an issue; it was a full-scale national emergency, a humanitarian crisis threatening the country’s ability to rebuild. The government recognized that to revive the economy, they had to provide housing for the workforce. You can’t drive an industrial miracle if workers are living in squalor. The traditional approach of small, privately built wooden houses was inadequate given the vast destruction and slow rebuilding pace. They needed a radical, rapid, efficient, and large-scale solution.

From Ashes to Apartments

This is when the government made a transformative decision. In 1955, they founded the Japan Housing Corporation (JHC), now known as UR or the Urban Renaissance Agency. Its mission was both simple and ambitious: to deliver a vast supply of modern, high-quality, fireproof, and affordable rental housing for the rapidly growing urban working class. This state-led, top-down initiative was immense in scale. The JHC wasn’t just constructing a few apartment buildings; they were creating entire towns from the ground up. They acquired large tracts of land on city outskirts—previously farmland or hills—and began to develop infrastructure for a new way of living. The danchi was more than just a building; it was a comprehensive concept and environment. The goal was to build not just houses, but stable, healthy communities where new generations of Japanese families could prosper. Japan was betting on itself, investing its scarce resources in concrete and steel as a stake in its own future.

The “nLDK” Revolution: Engineering a New Lifestyle

The true innovation of the danchi was inside the homes. The JHC introduced a floor plan that fundamentally changed Japanese domestic life: the “nLDK” design. This acronym, now ubiquitous in Japanese real estate, describes the functional layout of a home: ‘n’ stands for the number of bedrooms, ‘L’ for living room, ‘D’ for dining room, and ‘K’ for kitchen. Before the danchi, most Japanese lived differently. Traditional houses had multipurpose rooms with tatami mats and fusuma sliding paper doors—one room might serve as a living area by day, dining room by evening, and bedroom by night. The idea of distinct, dedicated spaces was a Western import, and the danchi established it as the new norm. The most revolutionary feature was the “DK” or “Dining Kitchen.” Drawing inspiration from German and other European social housing models, the JHC designed a bright, clean space combining the kitchen and dining area. This repositioned the kitchen—from a dark, smoky, utilitarian room at the back of the house—to the heart of family life. It was intended as the modern housewife’s efficient and cheerful command center. For families transitioning from cramped, dark, often unsanitary post-war homes, a danchi apartment with its own private toilet, modern kitchen sink, and clearly defined areas for eating and sleeping felt like stepping into the future. It was a monumental lifestyle upgrade, a concrete piece of the promise of post-war prosperity.

The Danchi Aesthetic: A Masterclass in Standardization

So, why such relentless uniformity? Why do danchi complexes all resemble one another so closely? The answer lies in a combination of harsh pragmatism and idealistic vision. Japan urgently needed millions of homes. In that context, efficiency became the highest priority. The aesthetic of the danchi didn’t stem from any single architect’s creative vision; it emerged from the logic of factory-style assembly lines.

Why the Uniformity? The Gospel of Efficiency

The JHC was a pioneer in using prefabricated concrete panels and standardized building parts. Everything—from window frames and balcony railings to kitchen units and bathroom fixtures—was mass-produced to exact specifications. This industrialized approach made it possible to build apartment blocks at an unprecedented speed and scale. It was the Fordism of housing. This standardization wasn’t considered a failure of creativity but celebrated as a triumph in modern engineering and planning. In a society still recovering from war’s devastation and past inequalities, this uniformity had a strong democratic appeal. Every family, regardless of background, received the same modern, clean, and functional apartment. The identical concrete facades symbolized a new kind of equality—a collective step toward a brighter, more orderly future. The relentless grid of windows and balconies visually represented a society rebuilding itself on rational, egalitarian principles. It was a feature, not a flaw.

The “Three Sacred Treasures” and the Danchi Dream

The danchi lifestyle was closely tied to the consumer boom of the 1960s, the peak of Japan’s economic miracle. Living in a danchi was the ultimate status symbol for the emerging middle class. The dream wasn’t just about the apartment itself but about what you could fill it with. The goal was to acquire the “Sanki no Jingi,” or the “Three Sacred Treasures” of modern life—a playful reference to Japan’s Imperial Regalia. These treasures were a black-and-white television, an electric washing machine, and a refrigerator. Danchi apartments were literally designed around these appliances, equipped with the electrical outlets, plumbing hookups, and designated spaces to accommodate them. Owning these three items in a shiny new danchi was the pinnacle of 1960s aspiration—it meant you had truly made it. Demand for danchi was so high that the JHC had to hold lotteries for available units, with odds sometimes reaching hundreds or thousands to one. Families erupted in celebration upon winning, as if they had struck gold—a golden ticket to the modern, comfortable life everyone in Japan was chasing.

Brutalism or Utopianism? The Architectural Vibe

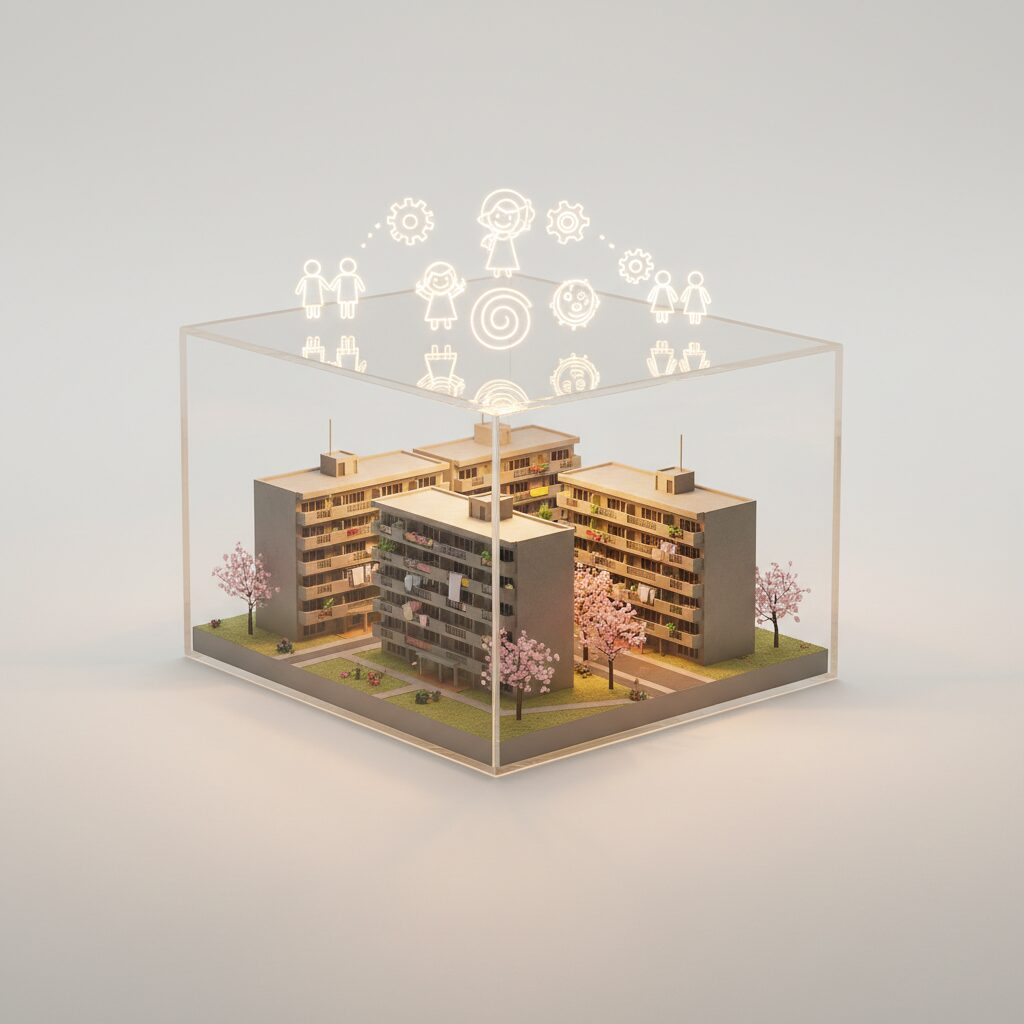

Looking at the large, raw concrete structures today, it’s easy to classify them as Brutalist architecture. While they share visual traits with Brutalism—the honest use of materials, monumental scale, repeating geometric forms—the underlying philosophy was different. Brutalism often embodied an ethical stance of revealing the ‘truth’ of construction. The danchi philosophy was more utopian and social. These complexes weren’t meant to be grim, imposing forts. They were envisioned as bright, airy, self-contained future communities. The architects and planners were creating “New Towns.” They didn’t merely erect apartment blocks; they designed entire ecosystems around them. The vast spaces between buildings were filled with green parks, playgrounds, baseball diamonds, and tennis courts. Each major complex had a central shopping arcade (shotengai), housing a supermarket, post office, clinic, and small family-run shops. Kindergartens and elementary schools were integrated into the community. The goal was for residents to have everything they needed within walking distance. Using reinforced concrete also carried deep symbolism: it marked a definite break from the past. Traditional Japanese cities, largely built of wood and paper, were highly vulnerable to fire and earthquakes. Concrete was solid, permanent, and fireproof—the material of a modern, resilient, scientific Japan, a nation building a future that could not be easily destroyed.

The Social Fabric of the Concrete Jungle

The impact of the danchi extended far beyond architecture and urban planning. These complexes became vast social laboratories, creating new types of communities and social identities. They fundamentally transformed Japanese family and neighborhood life, forming a new social fabric distinct from the rural villages or traditional urban neighborhoods of the past.

Building Communities from Scratch

The first wave of danchi residents consisted predominantly of young, nuclear families: a salaried husband, a full-time housewife, and one or two children. These families were often migrants to the city, having left their hometowns and extended families behind in search of opportunities in the booming industrial economy. In the danchi, everyone was initially a stranger, starting from the same point. With no old hierarchies or long-established family ties determining social status, a unique environment arose where a new kind of community had to be built from scratch. Neighbors, all sharing similar aspirations and a modern lifestyle, quickly formed strong bonds. Residents’ associations organized community events such as summer matsuri (festivals), undokai (sports days), and mochi-pounding ceremonies to foster a sense of belonging. Playgrounds and parks became social hubs where children played together and their mothers forged lifelong friendships. The term “danchi-zuma” (danchi wife) emerged as a key social archetype of the time. These women were the primary architects of community life, organizing childcare circles, cooking clubs, and mutual support networks. Navigating the new challenges of urban life away from the watchful eyes of their mothers-in-law, they created a vibrant and supportive social world within the concrete walls of the complex.

The Dark Side of the Dream: Isolation and Anonymity

However, as the decades passed, cracks began to appear in the utopian vision of the danchi. The very uniformity that had once symbolized equality started to feel monotonous and dehumanizing for some. Identical doors, hallways, and buildings fostered a sense of anonymity and disorientation. By the 1970s, a darker narrative began to take shape. The media reported on a phenomenon called “danchi-byo” or “danchi sickness,” described as a kind of depression and anxiety affecting housewives who felt trapped and isolated in their cookie-cutter apartments. Though sociologists debate the reality of this ‘sickness,’ the term reflected growing unease with the danchi lifestyle. The strong social bonds of the early years weakened as the original generation of children grew up and left. Playgrounds that had once been lively grew quiet. The promise of a close-knit community could dissolve into the reality of lonely lives lived side by side, separated only by thin concrete walls. The concrete jungle, once a symbol of connection and shared progress, could also become a place marked by profound modern loneliness. This shift in perception signaled the end of the danchi’s golden age and the start of its complex and often troubled middle age.

The Danchi Today: Nostalgic Ruins or Retro-Chic Revival?

Fast forward to the 21st century, and the danchi now holds a unique and intriguing position in the Japanese landscape. Many of these complexes are over fifty years old. They have ceased to be shiny symbols of the future and have instead become relics of a past era. Facing the dual challenges of aging infrastructure and an aging population, danchi are also undergoing a cultural revival, viewed through a fresh lens of nostalgia and aesthetic appreciation.

The Aging of a Generation and Its Buildings

The most urgent issue confronting many danchi today is demographic change. The young families who moved in with optimism during the 1960s and 70s have now grown elderly. Their children have long since left, often relocating to newer, more spacious suburban homes or city-center condominiums. Consequently, many danchi have transformed into “gray towns,” characterized by a disproportionately large elderly population. This shift has created serious social problems. Once-strong community bonds have weakened, leaving many seniors isolated. The phenomenon of kodokushi, or “lonely deaths,” where elderly individuals die alone and remain undiscovered for days or weeks, is a tragic reality commonly linked to aging danchi residents. Alongside the aging population, the buildings themselves are deteriorating. Concrete cracks, pipes corrode, and the once-modern interiors now seem outdated and cramped by today’s standards. Many complexes contain vacant units, while the small shopping arcades at their centers struggle to survive, with numerous shops closed down. Once engines of Japan’s growth, danchi now stand as stark reminders of the country’s demographic challenges.

The UR Renaissance: Renovation and Rebranding

However, this is not the entire story. The UR, the modern successor to the JHC, is actively preventing these vast housing stocks from falling into disrepair. They have launched a large-scale campaign of renovation and rebranding to revitalize the aging concrete structures. Acknowledging that the old, uniform layouts no longer appeal to everyone, they now offer renovated and customizable apartments. One of their most notable and successful projects is the collaboration with the minimalist lifestyle brand MUJI. The “MUJI x UR” initiative strips old danchi units down to their bare concrete shells and installs new, simple, and stylish interiors featuring light wood floors, open-plan kitchens, and versatile spaces. These renovated units are highly popular with a new wave of residents—young creatives, couples, and small families—drawn by the minimalist design, relatively affordable rent, and a strong sense of community. UR is also making it easier for younger people and foreigners to move in by removing many traditional rental barriers in Japan, such as large deposits, “key money” (a non-refundable gift to landlords), and the need for guarantors. They aim to reposition danchi not as outdated, second-rate housing but as a smart, trendy, and community-centered lifestyle option.

Danchi as a Cultural Icon: The Nostalgia Boom

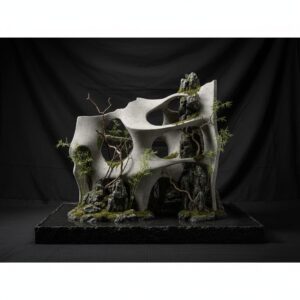

Beyond official renovation efforts, danchi is experiencing a significant cultural resurgence. For younger generations not burdened by the stigma of danchi decline, these concrete landscapes hold a strong aesthetic appeal. Nostalgia for the Showa Era (1926-1989), the period of Japan’s post-war economic boom, is growing, and danchi stand as one of its most powerful visual symbols. They frequently appear in popular culture. In anime like Danchi Tomoo and films by directors such as Hirokazu Kore-eda, danchi serve as backdrops for stories about family, community, and everyday life. Photographers are attracted to the stark geometric beauty of the buildings, the interplay of light and shadow on concrete, and the poignant atmosphere of aging complexes. This aesthetic is sometimes called ero-sabi—a fusion of the alluring and the decayed. It captures a beauty found in imperfection and the passage of time. Danchi are no longer just places to live; they evoke a mood, a vibe. They symbolize a tangible link to a more optimistic, though simpler, era in Japan’s recent history. They remind us of a collective national endeavor, a time when the nation was united in its dream of building a better future—a dream literally cast in concrete.

Visiting a Danchi: An Urban Explorer’s Guide

So you’re intrigued. You want to visit one of these places yourself. This isn’t about checking off a tourist spot from your list. It’s about urban archaeology—learning to read the landscape and uncover the stories embedded in the concrete. When you step into a danchi, you enter a living museum of post-war Japanese life.

Beyond Buildings: Reading the Landscape

Forget searching for a single landmark. The charm of the danchi lies in the details of its carefully planned environment. As you stroll through the complex, notice the spaces between the buildings. These aren’t empty gaps; they were intentionally designed as communal living rooms. Look out for the playgrounds. Many older danchi boast incredible, almost surrealistic concrete play sculptures—pandas, elephants, robots, and abstract geometric shapes—that have become cherished relics of Showa-era design. Observe the layout of the shotengai, or shopping arcade. Are the shops still open? What do they offer? The condition of this commercial hub often reveals the community’s vitality. Examine the balconies. Despite their uniform structure, you’ll find remarkable variety. Some are overflowing with potted plants, others have laundry hanging in orderly rows, while some remain empty. Each balcony offers a small portrait of the life lived within. These details—the worn paths in the grass, community boards plastered with notices, the well-tended flower beds planted by residents—are the essence of the danchi.

A Few Iconic Examples (To Illustrate These Ideas)

While danchi are widespread, a few stand out as especially significant. These aren’t necessarily the “best,” but they represent key chapters in the danchi story.

Takashimadaira Danchi (Tokyo)

Located in northern Tokyo, this vast complex is a concrete city built in the early 1970s. Its scale is astonishing and almost overwhelming. Takashimadaira symbolizes the height of the high-growth era’s ambition. It’s a prime example of all-inclusive planning, featuring its own subway station, schools, and commercial facilities integrated into the design. It also carries a darker, more complex history, having become notorious after a suicide incident in the 1980s, which solidified a negative public image of the danchi. Visiting here reveals both the grand utopian vision and the harsh social realities that followed.

Senri New Town (Osaka)

Nestled in the hills outside Osaka, Senri was among the first and most influential “New Town” projects in Japan, developed for the 1970 World Expo. It’s less a single danchi and more a vast collection of them, thoughtfully planned and blended with parks, ponds, and cultural centers. Senri is the textbook example of mid-century urban planning that viewed the danchi as the cornerstone of a fully designed modern environment. It’s a fascinating place to explore the origins of the entire concept.

Tokiwadaira Danchi (Chiba)

One of the classic, large-scale danchi from the early period, Tokiwadaira was built in the late 1950s. Its rows of simple, five-story walk-up buildings nestled in lush greenery exemplify the iconic image of the Showa-era danchi. It’s also been a pioneer in revitalization efforts. Walking through Tokiwadaira, you witness history layered upon itself—the original structures, signs of aging, and fresh renovations alongside community initiatives designed to attract younger generations. It’s a perfect case study of the danchi’s full life cycle.

The Etiquette of Observation

One final, crucial point: when exploring a danchi, remember these aren’t ruins or tourist attractions—they are people’s homes. The golden rule is respect. Observe quietly. Don’t trespass into buildings or take intrusive photos of residents or close-ups of their windows and balconies. Think of yourself as a respectful student of architecture and urban history. The goal is to understand and appreciate this unique part of Japan’s cultural landscape—not to treat it as a spectacle. Stick to public parks, pathways, and shopping areas. Remember, you are a guest in their neighborhood. A gentle walk, a coffee from a local shop, and thoughtful observation of your surroundings is the best way to experience the poignant, nostalgic, and deeply human world of the danchi.

So next time you see that endless grid of concrete balconies in a film or photo, you’ll know exactly what you’re looking at. It’s not just an old apartment block. You’re seeing the blueprint of modern Japan—a dream of prosperity and equality, a laboratory for new communities, a place of both connection and isolation. It’s a historical mood board, a story of a nation’s hopes and struggles cast in concrete, still reaching up toward the sky. For real.