Yo, what’s the deal? Let’s get real for a minute. When you picture Japan, you’re probably thinking neon-drenched Tokyo streets, serene temples in Kyoto, or maybe that perfect shot of Mount Fuji. And yeah, that’s all legit. But I’m here to put you on to something different, something with a whole other rhythm. We’re talking about ditching the bullet trains and crowded subways for a minute to vibe with the current. We’re talking about river punting, or as the locals call it, kawakudari. This ain’t your average tourist trap boat ride. Nah, this is a full-on time-travel experience, a way to see Japan from a perspective that’s been rolling for centuries. You’re gliding down ancient waterways, canals dug by samurai engineers, piloted by a master boatman with nothing but a single bamboo pole and a whole lot of soul. It’s slow travel at its finest, a chance to actually breathe and see the landscape unfold. You’re not just looking at history; you’re floating right through it. This is the Japan that’s hiding in plain sight, a liquid artery connecting the past to the present. So, strap in, get comfy, ’cause we’re about to dive deep into the world of Japanese river punting. It’s a whole mood, a piece of living culture that’s straight-up essential for anyone trying to understand the heart of this country. It’s the real deal, no cap.

For more unique Japanese experiences beyond the waterways, discover how Nikko Style Niseko HANAZONO was crowned the world’s best new ski hotel.

The OG Waterways: A Quick History Sesh

Alright, let’s break it down. To truly understand why these boat rides are so incredible, you need to know their backstory. These canals and rivers weren’t created just for your scenic Instagram shots. They were the backbone of society, especially during the Edo Period (1603-1868). This was a time before cars and trains. Water served as the information highway, the Amazon Prime delivery system, and the main line of defense all rolled into one. Castle towns, known as jokamachi, were designed with remarkable strategic brilliance, and water played a central role in that strategy.

Take a place like Yanagawa in Fukuoka. The Tachibana clan, who controlled the area, built an intricate network of canals called horiwari. On one level, these served as defensive moats, making it extremely difficult for rival warlords to approach the castle. But they were much more than that. These waterways were essential for irrigation, transforming the region into a fertile agricultural hub. They also acted as the main commercial routes. Barges and small boats were constantly moving, transporting rice, goods, and people. The entire economy literally flowed through these canals. So when you’re on a punt today, you’re riding on a legacy of military strategy, agricultural innovation, and economic activity. It’s powerful stuff, right? Every low bridge you duck beneath and every stone-walled bank you pass is a relic from that time. This wasn’t just landscaping; it was nation-building at the local level, a masterpiece of hydro-engineering that’s endured through the centuries. You’re not just a passenger; you’re witnessing the ghost of a feudal Japanese circulatory system still alive today.

The Sendo: Master of the Flow

You can’t talk about river punting without giving a huge shout-out to the true legends behind it: the sendo, or boatmen. These individuals are the heart and soul of the entire experience. Make no mistake, this isn’t just a summer job. It’s a craft, a skill, an art form passed down through generations. Clad in traditional attire—often a happi coat and a conical straw hat—the sendo stands at the stern, expertly guiding the boat with a single, long bamboo pole called a sao. The skill on display is astonishing. They pole, push, steer, and brake, all with this one simple tool. Watching them navigate narrow channels, glide beneath impossibly low bridges, and handle the boat with such grace and precision is a performance in itself. They make it seem effortless, but that’s the mark of a true master. It’s a lifetime of practice: learning to read the water’s mood, the wind’s direction, and the boat’s momentum. It’s a deep, physical connection to the environment. They know every bend, every rock, every overhanging willow branch like the back of their hand. They are living libraries of the river.

But the sendo is more than just a pilot. They’re your guide, your storyteller, and often, your entertainer. They’ll point out historical landmarks, share local legends, and crack jokes. And the best part? Many will break into song. They sing traditional boatmen’s songs, or funauta, their voices ringing across the water. It’s hauntingly beautiful. A song like the “Yanagawa Kouta” isn’t just a melody; it’s an oral history of the town, full of emotion and local pride. This is where the experience goes beyond mere sightseeing and becomes something deeply cultural and human. You’re not just taking in the scenery; you’re connecting with a person whose identity is inseparable from that very water. So listen closely, show your appreciation, and respect the master at work. The sendo is the keeper of the flame, ensuring this incredible tradition doesn’t simply fade away into history.

The Holy Trinity of Punting Spots

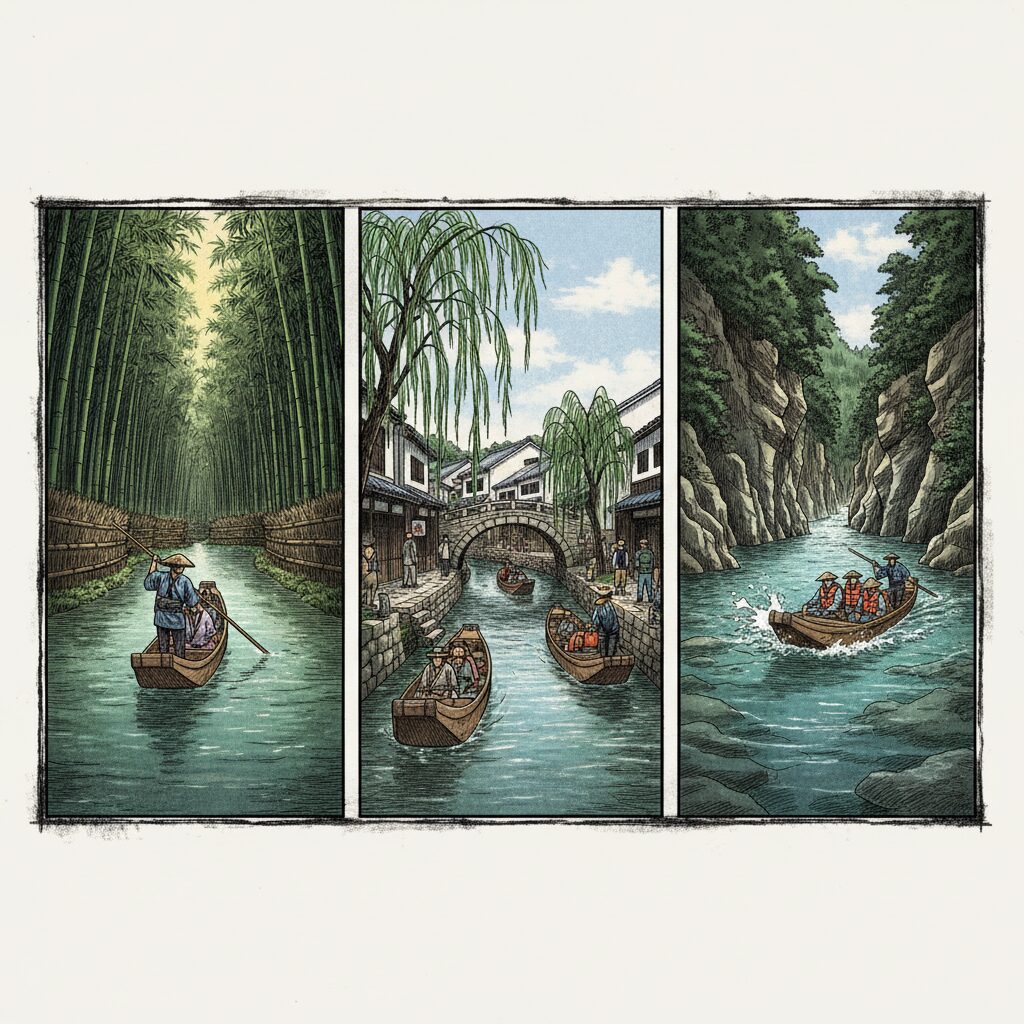

While these peaceful boat rides can be found in a few locations across Japan, there are three main destinations, each offering its own unique and unforgettable atmosphere. Each one provides a different experience, allowing you to choose based on the kind of adventure you seek.

Yanagawa, Fukuoka: The Venice of Japan

This is the undisputed leader and emblematic example of Japanese river punting. Situated in southern Fukuoka Prefecture on Kyushu island, Yanagawa is a former castle town defined by its extensive waterways. The town is woven with around 470 kilometers of canals, best explored from a flat-bottomed boat known as a donkobune. The journey is pure poetry, lasting about 70 minutes as you glide serenely through a maze of waterways, far removed from the city’s hustle and bustle.

The atmosphere is enchanting. Weeping willows line the canal banks, their branches dipping into the water. You’ll pass traditional white-walled storehouses and the secluded gardens of old samurai homes, glimpsing a world usually hidden from street view. The mood is slow, contemplative, and stunningly beautiful. Ducks paddle alongside, koi swim beneath the clear water, and the landscape shifts with the seasons. In spring, it becomes a tunnel of cherry and peach blossoms; summer brings irises in full bloom, bursting with purple and white. Moments of playful excitement punctuate the ride as you approach one of the many low bridges—the sendo calls out, and all aboard must duck low to pass underneath. This simple act connects you to the experience, turning you from observer to participant. The trip ends near the Ohana Villa, former home of the Tachibana clan, an ideal place to explore after your boat ride. For first-timers, Yanagawa offers a gentle, beautiful introduction steeped in history. And here’s a major tip: after your ride, don’t miss trying the local specialty, unagi no seiro-mushi—steamed eel on rice—a perfect way to conclude a perfect day on the water.

Hozugawa, Kyoto: The Thrill Ride

If Yanagawa feels like a peaceful lyrical poem, the Hozugawa River boat ride is a full-throttle action film. Designed for thrill-seekers, this 16-kilometer, two-hour course runs from Kameoka down to Kyoto’s iconic Arashiyama district. Here, you’re not on a calm canal but a dynamic river, carving its path through a breathtaking, rugged gorge. The boats are larger to manage more challenging waters, piloted by a trio of sendo working in perfect sync. One steers with a rudder from the back, another uses a long bamboo pole at the front to push off rocks, and the third helps navigate the rapids. Their teamwork is a stunning display of coordination and strength.

The scenery is spectacular. Towering forested mountains plunge dramatically to the water’s edge, and the river shifts from tranquil emerald pools to roaring whitewater rapids. The ride alternates between serene moments to absorb the surroundings and heart-pounding excitement as the boatmen expertly guide through rocky stretches. Seasonal beauty is a highlight—spring brings wild cherry blossoms and azaleas clinging to slopes; summer reveals deep lush greens. But autumn is when Hozugawa truly shines: the gorge bursts into a fiery palette of reds, oranges, and golds. It’s one of Japan’s premier spots for autumn leaves (momiji), and viewing them from the river is an unparalleled experience. As the ride nears its end in Arashiyama, the landscape opens up to the famous Togetsukyo Bridge—an impressive finale to an unforgettable journey. This ride emphasizes the raw power and beauty of nature, offering an exhilarating adventure that leaves you energized.

Geibikei, Iwate: The Serene Gorge

Far to the north in the Tohoku region lies Geibikei Gorge in Iwate Prefecture, offering a third, distinctly tranquil style of river punting. Recognized as one of Japan’s 100 most scenic spots, Geibikei is set in a magnificent limestone gorge with towering cliffs rising over 50 meters on both sides. The name Geibi means “Lion’s Nose,” inspired by a rock formation at the gorge’s end resembling a lion’s snout. This experience is all about calmness and awe.

The journey is a 90-minute round trip, with a single sendo—often a woman—poling the boat slowly up the gorge. The water is calm and crystal clear, mirroring the cliffs and sky above. It’s incredibly quiet, punctuated only by the gentle splash of the pole, bird calls, and occasional rustling of a Japanese serow on the cliffs. The atmosphere demands reverence. The sendo points out various rocks shaped like animals or mythical beings. At the turnaround, everyone disembarks for a short walk to see the main Geibikei rock formation. A delightful tradition allows you to buy small flat stones called undama (luck stones), each inscribed with characters symbolizing luck, love, or fortune. You try to toss them into a small opening in the cliff across the river; if successful, your wish is said to come true. This charming, interactive custom adds to the experience. The true highlight of the return trip arrives when the sendo sings “Geibi Oiwake,” a local folk song. The gorge’s natural acoustics carry the voice, creating a truly spellbinding echo that sends chills down your spine. Geibikei is a profoundly moving encounter—a spiritual cleanse that connects you with the serene grandeur of nature.

More Than Just a Ride: Digging Deeper

There are several other fantastic places to enjoy punting, each offering its own unique local charm. Although these rides may be shorter, they deliver a powerful experience in terms of atmosphere and history.

Omihachiman, Shiga

Situated on the shores of Lake Biwa, Japan’s largest lake, Omihachiman is a beautifully preserved merchant town. Its canals were constructed in the late 16th century by the orders of Toyotomi Hidetsugu, a powerful samurai lord. These waterways played a crucial role in the success of the Omi merchants, who became some of the most influential traders in Japan. A boat ride here is a journey through economic history. You’ll glide past traditional houses and storehouses, beneath picturesque stone bridges, gaining a true sense of the town’s former prosperity. The ride is especially stunning in early spring when the banks are decorated with fields of yellow rapeseed flowers and cherry blossoms. It offers a more compact experience than Yanagawa but is equally charming. It feels as though you’ve discovered a hidden gem, a tranquil corner of history perfectly preserved.

Kurashiki, Okayama

Kurashiki’s Bikan Historical Quarter feels like stepping onto a movie set. This area was once a major rice distribution hub during the Edo Period, and its canal is lined with impressive old rice granaries, or kura. These granaries are notable for their black-and-white, geometric-tiled walls and imposing architecture. The canal itself is small, and the boat ride is a brief but remarkably scenic 20-minute loop. What a loop it is. Led by a sedge-hatted boatman, you drift past weeping willows and under ancient stone bridges. It’s incredibly photogenic. Because the ride is so short, it fits easily into a day of exploring the Bikan district, which is now home to art museums (including the renowned Ohara Museum of Art), cafes, and boutiques housed within the old granaries. The Kurashiki ride is the perfect historical appetizer, a concentrated taste of Edo-period atmosphere that will leave you craving more.

The Four Seasons of Flow: When to Go

The atmosphere of a river punting experience shifts dramatically with the seasons, and honestly, there’s never a bad time to go. It all depends on what you’re hoping to find.

Spring (March – May)

This is peak season for a reason. Japan’s famous cherry blossoms, or sakura, turn the waterside scenery into a pastel wonderland. In places like Yanagawa and Omihachiman, you’ll glide beneath canopies of pink and white blooms. It’s incredibly romantic and beautiful. The weather tends to be mild and pleasant, ideal for outdoor activities. It can get crowded, so be prepared, but the spectacle is absolutely worth it. Yanagawa also holds a special Hina-matsuri (Girl’s Day) festival during this period, featuring elaborate doll displays and floating decorations on the canals.

Summer (June – August)

Summer brings a lush, vibrant green to the landscape. The foliage is thick and full, providing welcome shade. This is the season to see irises in full bloom along the banks in Yanagawa. On the Hozugawa, the deep green mountains contrast stunningly with the sparkling water. It can be hot and humid, so dress accordingly and bring a hat. Yet, there’s a unique energy to a summer boat ride—a feeling of life at its peak. In some areas, you might even enjoy an evening ride to see fireflies, which is truly magical.

Autumn (September – November)

For many, this is the ultimate season. The “autumn foliage” season, or koyo, showcases Japan’s maple and ginkgo trees bursting into spectacular shades of red, orange, and gold. The Hozugawa Gorge in Kyoto becomes a world-renowned destination, with the boat ride offering a front-row view of one of nature’s grandest shows. Geibikei Gorge is equally stunning, as the fiery colors of the trees stand out against the grey limestone cliffs. The air is crisp and cool, and the scenery is breathtaking. It’s a photographer’s dream and a deeply moving time to be on the water.

Winter (December – February)

Don’t overlook winter punting! Yes, it’s cold, but the Japanese have a clever solution: the kotatsu-bune. These are boats equipped with a kotatsu, a low table heated underneath and covered with a thick quilt to trap the warmth. Sitting with your legs tucked under the cozy quilt, sipping warm sake as you glide through a starkly beautiful winter landscape, is a unique experience. Seeing places like Yanagawa or Geibikei dusted with snow offers a serene, entirely different perspective. The crowds disappear, and there’s a deep sense of peace on the water. It’s the coziest, most distinctively Japanese way to enjoy the scenery, proving river punting is a truly year-round activity.

The Practical Stuff: Know Before You Go

Alright, let’s dive into the details. Careful planning is essential for a smooth trip.

Access & Booking

Getting to these destinations is generally easy using Japan’s excellent public transportation.

- Yanagawa: From Fukuoka (Tenjin), take the Nishitetsu Tenjin-Omuta Line directly to Nishitetsu Yanagawa Station, about a 50-minute ride. The boat operators are within walking distance or a short taxi ride from the station. Most trips are one-way, with shuttle buses or taxis available to return you to the station area from the disembarkation point.

- Hozugawa: From Kyoto Station, board the JR Sagano Line (also known as the Sanin Main Line) to Kameoka Station. The boat launch is a brief walk from there. The ride ends in Arashiyama, where you can explore before catching a train back to central Kyoto.

- Geibikei: This one is a bit more remote. From Ichinoseki Station (on the Tohoku Shinkansen line), take the JR Ofunato Line to Geibikei Station. The boat pier is just a five-minute walk away.

For most rides, especially outside peak seasons, it’s usually fine to buy tickets on the spot. However, during Golden Week, cherry blossom season, or autumn foliage season, booking in advance through official websites (if available) or via travel agents is recommended to avoid disappointment. For the Hozugawa ride in particular, advance booking is almost always advisable.

What to Expect & What to Bring

- Duration: Rides vary from 20 minutes (Kurashiki) up to 2 hours (Hozugawa). Be sure to confirm how long you’ll be on the water.

- Facilities: You’ll be on simple, traditional boats with no bathrooms onboard, so use the facilities before boarding.

- What to Wear: Dress for the weather in comfortable clothes. Since you’ll be sitting on cushions on the boat floor, flexible clothing is best. Wear easy-to-remove shoes.

- What to Bring: A camera is a must. In summer, sunscreen, sunglasses, and a hat are essential. In colder months, bring extra layers—even if you’re on a kotatsu boat. You can usually bring your own drinks and snacks on board, which can enhance your experience.

Final Thoughts on a Liquid Legacy

To drift along one of Japan’s historic waterways is more than just sightseeing. It’s an invitation to slow down to the pace of a bamboo pole gently pushing against the riverbed. It offers a chance to embrace the rhythm of a tradition that has endured centuries of change. You disconnect from the hectic rush of modern life and connect with something elemental and timeless. The boat’s gentle rocking, the sound of the water, and the voice of the sendo drifting on the breeze create a form of meditation. You experience the country from the inside out, through the waterways that once sustained it and still carry its memories. It’s a deep connection to the past and a beautiful way to appreciate the present. So, next time you’re in Japan, look beyond the skyscrapers and temple gates. Head to the water’s edge, board a boat, and let the current guide you. This journey is about more than the destination—it’s about the flow. Believe me, it’s an unforgettable vibe.