Alright, let’s get real for a sec. You’ve seen it. I’ve seen it. We’ve all doomscrolled past it at 2 AM. The lone samurai, silhouetted against a blood-red moon, katana gleaming, ready to face down an entire army. He’s the main character, and his defining trait, besides being impossibly cool, is a total lack of fear of death. In fact, he seems to be actively vibing with the whole concept. From classic Kurosawa flicks to the latest season of that one anime you’re binging, the samurai aesthetic is deeply intertwined with a philosophy of dying beautifully, of choosing a perfect end over a messy, long life. It’s the ultimate act of commitment, the final, brutal poetry of the warrior. But low-key, doesn’t it feel a little… extra? Why this intense, almost romantic fixation on death? Was every samurai really walking around with a death wish, ready to commit seppuku if their boss looked at them funny? It’s one of those things about Japan that seems both fascinating and completely bonkers from the outside. You start to wonder, what’s the source code for this whole vibe? Well, a huge chunk of that code can be found in a single, controversial, and deeply misunderstood book: Hagakure. This text, whose title translates to “In the Shadow of Leaves,” is often held up as the quintessential guide to the samurai spirit, the OG Bushido bible. But here’s the plot twist, the part that changes everything: Hagakure wasn’t written by a battle-hardened warrior in the thick of a chaotic civil war. It was dictated by a retired samurai administrator over a century into the longest, most peaceful period in Japanese history. It’s a book about the glory of dying in battle written when there were no battles to be fought. And understanding that paradox is the key to unlocking why this idealized, death-centric version of the samurai has had such a chokehold on the world’s imagination for centuries. It’s less of a historical account and more of a philosophical manifesto born from a profound identity crisis. Before we dive deep into this rabbit hole, let’s get our bearings. The story of Hagakure begins in the Saga Domain, a quiet corner of Kyushu. Peep the location, because geography is half the story.

This profound connection between the warrior’s spirit and Japanese craftsmanship is further explored in how the legacy of the samurai sword continues to shape the nation’s culture, from its blades to its philosophy.

The Vibe Check: What Even Is Hagakure?

So, before we proceed, let’s clarify what Hagakure is—and, more importantly, what it isn’t. If you’re imagining a dusty scroll packed with ancient battle tactics like Sun Tzu’s Art of War, you’re completely mistaken. This isn’t your grandfathers’ war journal. It’s not a continuous narrative. Rather, it’s a collection of over 1,300 brief anecdotes, commentaries, and life lessons dictated between 1709 and 1716 by a samurai named Yamamoto Tsunetomo to a younger scribe, Tsuramoto Tashiro. The entire text was compiled after Tsunetomo retired from his clan duties and became a Buddhist monk living in seclusion. This context is crucial. Tsunetomo was a man looking back, not forward. Born in 1659, long after the famous Sengoku Jidai, or “Warring States Period,” had ended, he lived during the Edo Period, which began in 1603 when the Tokugawa shogunate unified Japan, ushering in 250 years of peace and stability. Tsunetomo never experienced actual combat. His samurai life consisted of service, administration, and managing the intricate social politics of his lord’s court. His fixation on a warrior’s death was purely theoretical, stemming from nostalgia for a more “authentic” samurai era he had only heard about.

Not Your Grandfather’s War Journal

The book’s structure itself reveals much about its purpose. It’s messy, contradictory, and intensely personal. One passage may offer advice on behavior at a drinking party, the next critiques a recent Noh performance, and another recalls a brutal tale about a legendary swordsman from two centuries earlier. It’s less a coherent philosophy and more like a series of private conversations—an older employee’s candid rant about “how things used to be” that happened to be recorded and preserved. Tsunetomo himself ordered the manuscript to be burned upon his death, implying he never intended it for a wider audience. It was a secret text, a clan-specific manual for the Nabeshima samurai of Saga, designed to instill a particular mindset—a distinct local brand of warrior ethics. It wasn’t meant to serve as a universal code for all samurai across Japan. The book radiates intense local pride, continuously praising the Saga way while disparaging the more refined, “soft” samurai of cities like Edo (modern Tokyo) and Kyoto. It represented an effort to preserve a hard-edged, provincial warrior spirit amid rising metropolitan sophistication.

“The Way of the Warrior is Death” – The 18th Century Quote That Went Viral

Now, let’s discuss the line everyone knows, even if they’ve never heard of the book: “I have found that the way of the samurai is death.” In Japanese, Bushidō to wa shinu koto to mitsuketari. It’s arguably one of the most intense—and most misunderstood—phrases in history. On the surface, it sounds like a call for self-destruction, as if a warrior’s primary goal is death itself. But that’s a huge oversimplification. Tsunetomo’s meaning is far more psychological. He suggests that by meditating on death daily and accepting it as inevitable—being constantly ready for it—a warrior frees himself from the fear of death. Once fear is removed, one can act with complete clarity, decisiveness, and freedom in every moment. It’s about achieving a state of intense focus. If faced with a choice between life and death, you should choose death without hesitation. Why? Because hesitation, worry about consequences, or striving to save your own skin leads to failure and disgrace. Choosing death instantly purifies your intentions. You act with full commitment to your duty, free from selfish desires to survive. Think of it like a pro athlete in the final seconds of a championship game—they can’t be thinking, “What if I miss this shot and become a joke?” They must block out all fear of failure and just act. For Tsunetomo, death was the ultimate mental barrier, and overcoming it mentally unlocked a warrior’s true potential. It wasn’t about seeking death, but being so prepared for it that it ceased to influence one’s actions. This mindset enabled a samurai to serve his lord with absolute loyalty, unclouded by personal ambition or fear.

Samurai in Peacetime? The Identity Crisis That Birthed a Vibe

To truly understand why a book like Hagakure was created, you need to grasp the profound identity crisis the samurai class experienced during the Edo Period. For centuries, warfare was their entire purpose. They were the military elite, fighting and dying for their lords to gain land and power. The term samurai literally means “one who serves.” But when Tokugawa Ieyasu won the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 and established his shogunate, the fighting stopped. The relentless, brutal wars that had shaped Japan for over a hundred years came to an end. What followed was the Pax Tokugawa, a prolonged peace that rendered the samurai’s primary skills largely obsolete.

From Warriors to Bureaucrats

Suddenly, this vast warrior class, making up about 7% of the population, had no battles to fight. Yet they remained. They still held the top position in the rigid social hierarchy (known as Shinōkōshō: Samurai, Farmers, Artisans, Merchants) and retained the exclusive right to wear two swords. However, their daily roles shifted dramatically. They transformed from warriors into civil administrators, bureaucrats, and courtiers. They managed farmlands, collected taxes, and spent their time navigating the complex and often petty politics within their lord’s castle. Essentially, they became middle managers armed with swords they were forbidden to draw. Duels were banned, and unauthorized fighting was harshly punished. This led to a deep psychological conflict: their identity was based on martial skill and readiness to die in battle, but their reality was paperwork and peaceful routine. It’s akin to a modern Special Forces operative suddenly reassigned to a permanent desk job in accounting, yet required to appear in full combat gear daily. The potential for an existential crisis was tremendous.

Bushido’s Transformation

This context provided fertile ground for the concept of Bushido, the “Way of the Warrior,” to truly emerge. Although warrior codes had existed for centuries, the Edo period witnessed a significant effort to codify, philosophize, and romanticize what it meant to be a samurai. Deprived of battlefield proof of their worth, samurai sought to demonstrate it through character, unwavering loyalty, and impeccable conduct. Bushido evolved into a spiritual and ethical training system designed to preserve a warrior’s spirit in a warless world. Thinkers and samurai of the era wrote works that nostalgically looked back to the “golden age” of the Warring States period, painting a highly idealized and romantic view of the past. Hagakure stands as perhaps the most intense and passionate example of this trend. It is a vehement critique of what Tsunetomo saw as the softening and decadence of his contemporaries. He repeatedly laments that samurai of his time were weaker and more concerned with wealth and appearances than the fierce warriors of old. His book is a fervent call to preserve a spirit he believed was fading—a manual on how to feel like a samurai when traditional action was no longer possible.

The Highest Honor: Loyalty Beyond Life

In this new era of peace, according to Tsunetomo, the ultimate embodiment of the samurai spirit was absolute, fanatical loyalty to one’s lord, or daimyo. This loyalty demanded purity and selflessness. He maintained that a samurai should be ready to die for his lord instantly and without hesitation. This is the core of the ideal of “dying with a sword in hand.” With no wars in which to prove this loyalty, the preparedness to die itself became the expression of loyalty. This philosophy culminated in the practice of junshi, the ritual suicide of following one’s lord in death. Tsunetomo’s lord, Nabeshima Mitsushige, forbade his retainers from committing junshi upon his death in 1700, a blow that deeply affected Tsunetomo, who had wished to perform this ultimate act of fidelity. Denied this path, he chose to become a monk and record his thoughts, which became Hagakure. The entire work can be viewed as the product of this frustrated devotion—a philosophical outlet for his loyalty. His focus on death arose largely from being denied the death he believed he was owed. He elevated the readiness to die into the central tenet of samurai identity because, in an age of peace, it was the only remaining measure of martial honor.

Hagakure’s Main Character Energy: The Ideal vs. The Real

One of the biggest misconceptions about Hagakure is the belief that it was an instant bestseller widely read by samurai throughout Japan. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth. During most of the Edo period, the book remained an underground secret—a niche text dismissed by many contemporary samurai as too extreme and out of touch. Its evolution from an obscure clan manuscript to a symbol of the Japanese national spirit is a remarkable journey involving war, nationalism, and extensive historical reinterpretation.

A Niche Text Gains Popularity (Much, Much Later)

As noted earlier, Tsunetomo never intended for his words to be published. Hagakure was copied by hand and circulated only among the samurai of the Nabeshima clan. For more than 150 years, it remained virtually unknown outside Saga. At the time, other mainstream Bushido schools—such as the one promoted by the influential scholar Yamaga Sokō—were far more popular. Sokō’s interpretation was more balanced, blending Confucian ethics and emphasizing the samurai’s role as a moral and intellectual guide in a peaceful society. In contrast, Tsunetomo’s philosophy seemed rustic, outdated, and frankly, somewhat unhinged. His outright rejection of planning and focus on reckless, immediate action clashed with the more strategic, bureaucratic mindset typical of the mature Edo era. The book was a relic—a time capsule reflecting a mindset the majority of Japan had already moved beyond.

The Meiji Restoration and the Samurai’s Final Struggle

Hagakure’s status began to shift with the fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1868. The Meiji Restoration triggered rapid, top-down modernization. The new government, eager to modernize and catch up with the West, dismantled the old feudal hierarchy. During the 1870s, the samurai class was officially abolished; they lost their stipends, exclusive rights to carry swords, and elite social standing. This was an even deeper identity crisis. As Japan industrialized and embraced Western technology and customs, a strong nostalgia and quest for a distinctive “Japanese spirit” (yamato-damashii) emerged. Intellectuals began searching the past for answers to what being Japanese meant in this new, bewildering era. It was in this context that the once-forgotten, extreme philosophy of Hagakure gained appeal. It was pure, uncompromising, and distinctly Japanese. The first widely distributed printed edition came out in 1906, attracting a new audience among those alienated by modernization and longing for the supposed moral clarity of the past.

World War II: A Dark Reinterpretation

This is where Hagakure’s story takes its darkest turn. In the 1930s and 40s, as ultranationalist militarism gripped Japan, the government’s propaganda apparatus sought ideological fuel—and found it in Hagakure. They seized on its most radical passages, especially the infamous line “the way of the warrior is death,” stripping them of context. Tsunetomo’s original ideas centered on a samurai’s absolute, personal loyalty to his feudal lord. The imperial propagandists, however, warped this into a demand for unconditional, impersonal loyalty from every Japanese citizen to the Emperor and the State. Hagakure was recast as a call for self-sacrifice for the nation’s sake. Its teachings justified suicidal banzai charges and the kamikaze missions of the Special Attack Units. Young pilots were often given copies of the book and told that a glorious death in service to the Emperor was the highest expression of the Bushido spirit. This was a grotesque distortion. Tsunetomo wrote about the inner spiritual state of an individual warrior within a feudal framework, but his words were weaponized to endorse mass, industrialized death in a modern totalitarian war. The romantic ideal of “dying with a sword in hand” morphed into crashing a plane loaded with explosives into an enemy warship. This wartime appropriation solidified Hagakure’s reputation abroad as a “death cult” text, a version that, for better or worse, has profoundly shaped global perceptions.

Even after the war, the book’s influence endured. The controversial author Yukio Mishima, fascinated by what he perceived as Japan’s lost masculine spirit, was a devoted admirer of Hagakure. His life became a form of performance art aimed at reviving this ethos, culminating in his dramatic ritual suicide in 1970 after a failed coup attempt. For Mishima, Hagakure was a remedy against the passive, materialistic consumerism of post-war Japan. He remains perhaps the most famous modern figure to embrace the book’s ideals in their most literal and tragic form.

The Echo Chamber: How Hagakure Still Slaps in Pop Culture

So, after all that intense history, how does this 300-year-old book—born from a retired samurai’s existential crisis and later co-opted by imperial propagandists—still appear on our screens today? Because its fundamental aesthetic—the concept of finding freedom and purity through acceptance of death—is simply too powerful to vanish. It has become a cornerstone trope in Japanese storytelling, resonating through countless manga, anime, and video games, shaping the global perception of the Japanese hero.

Anime, Manga, and the Spirit of the Samurai

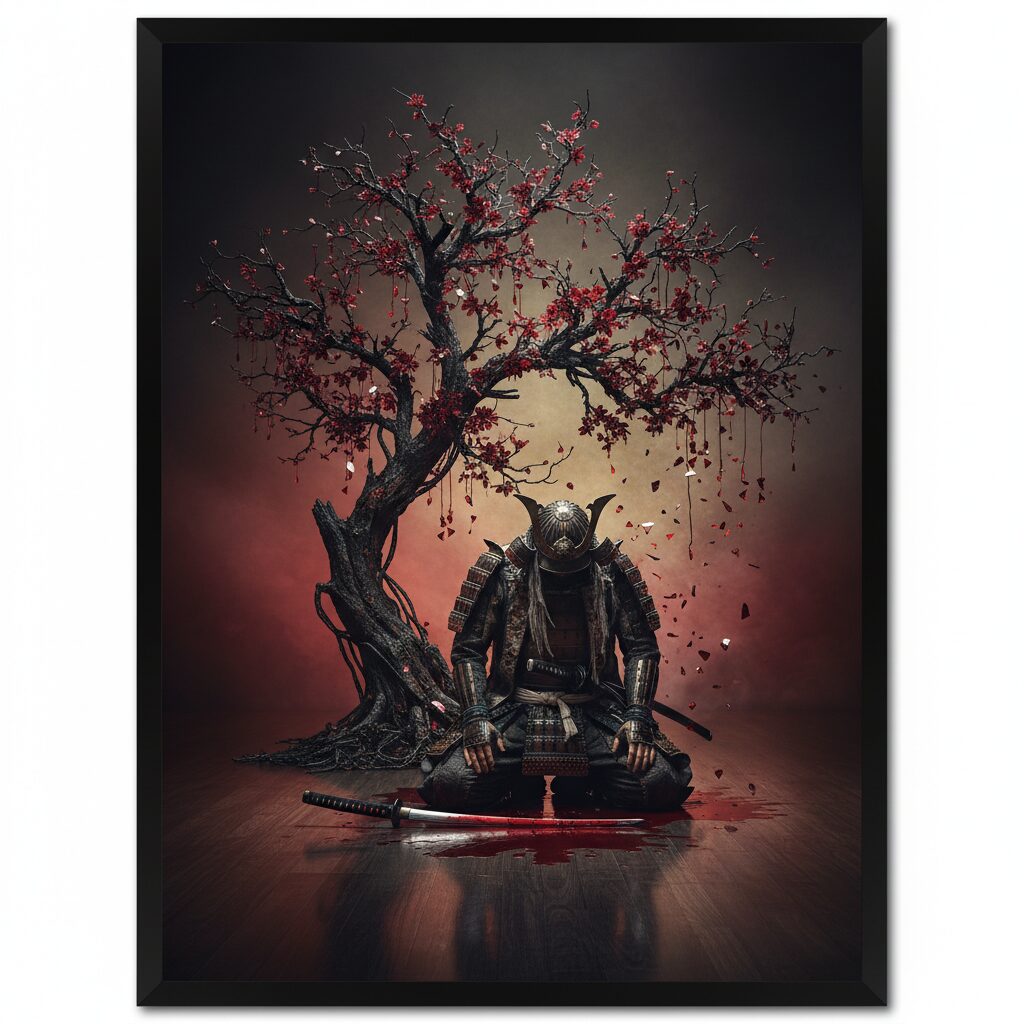

Consider your favorite shonen anime. How often have you seen a character, pushed to their absolute limit, suddenly smile and discover a new strength because they have accepted the possibility of death in battle? That is the spirit of Hagakure. When a character in series like Jujutsu Kaisen or Attack on Titan calmly declares their readiness to sacrifice their life for their comrades or cause, they embody this very specific philosophy. It is depicted as the highest form of resolve. Letting go of the fear of death reveals their true power. This isn’t just a generic “heroic sacrifice” trope typical in Western media; it is often portrayed as a deeply personal, internal spiritual triumph. The character is not merely brave; they achieve a state of enlightenment by embracing their own mortality. The cherry blossom, a profoundly significant symbol in Japan, is tied to the same idea. Its life is brilliant but fleeting, and its beauty is most poignant when the petals fall. This aesthetic, called mono no aware (a sensitivity to the transience of things), is cultural soil where the Hagakure ideal flourishes. The perfect death is the ultimate expression of a beautiful, meaningful life.

The Misunderstood Edgelord

This profound cultural concept is frequently oversimplified or misunderstood by international audiences. When we see a character obsessed with death, we might dismiss them as an “edgelord” or merely emo. And sure, sometimes that’s the case. But more often, it taps into this complex philosophical heritage. The character’s motivation is not suicidal despair but a pursuit of purity in action. In a world filled with compromise and ambiguity, the willingness to die for something is portrayed as the ultimate act of sincerity. It cuts through all the noise. Roronoa Zoro from One Piece, with his unwavering, almost fanatical loyalty to his captain Luffy and his readiness to face death for him, perfectly embodies the modern Hagakure retainer. His famous line, “If I can’t even protect my captain’s dream, then whatever ambition I have is nothing but talk,” could have been lifted directly from Tsunetomo’s writings. This dedication—placing a lord’s (or captain’s) ambition above one’s own life—is at the heart of this romanticized warrior spirit.

The Corporate Samurai? Not Really.

Now, it’s time to debunk a tired cliché: the idea of the Japanese “salaryman” as a modern corporate samurai. This was a common trope in Western business books from the 80s and 90s, trying to explain Japan’s economic success by claiming its corporate culture was rooted in Bushido values like loyalty, discipline, and self-sacrifice. While Japanese work culture does emphasize group harmony and long-term company commitment, equating the average office worker with the life-or-death extremism of Hagakure is a huge stretch. It’s a fantasy that overlooks the complexities of both historical samurai and contemporary Japanese life. The samurai in Hagakure was loyal to a person—his lord—not an abstract corporate institution. His sacrifice was meant to be a swift, decisive act of martial purity, not decades of unpaid overtime. Although the metaphor sounds appealing, it ultimately obscures more than it clarifies and reduces a rich philosophy to a simplistic business analogy. The spirit of Hagakure doesn’t dwell in Tokyo boardrooms; it lives in the pages of manga and frames of anime, where its hyper-romantic ideals can unfold without real-world consequences.

So, Did They Really Die With a Sword in Hand?

After all this discussion on philosophy, aesthetics, and propaganda, we must address the final, crucial question: Was the ideal of dying a beautiful death with a sword in hand the reality for most samurai? The short answer is a definitive no. The romantic image is just that—a romance, an ideal conceived and refined during a peaceful era, later exploited for political purposes.

The Reality Check

The vast majority of samurai throughout the 250-year Edo period died in the same manner as most people: from old age, illness, or accidents. They did not perish in glorious battle because there were no battles to fight. While the ritual of seppuku (or hara-kiri) was indeed real, it was not a frequent or commonplace event. It was a highly formalized and comparatively rare practice. It might serve as capital punishment imposed by a lord, allowing a samurai to die honorably rather than by execution. It could also be a voluntary act of protest against a lord’s decision, atonement for failure, or, in the case of junshi, following a lord in death. However, even junshi was considered wasteful and was officially banned by the shogunate in 1663, long before Tsunetomo wrote. Most samurai spent their lives managing their finances (many were surprisingly poor), honing their swordsmanship in ritualized dojos, and navigating the strict social hierarchy of their domain. The “sword in hand” death was a dream, not an everyday reality.

The Power of an Idea

Ultimately, the immense influence of Hagakure lies not in its historical accuracy or practical application during the Edo period, but entirely in the realm of ideas. The book did not describe what samurai were; it passionately proclaimed what one intensely nostalgic and frustrated man believed they should be. It captured a specific, extreme, and compelling aesthetic of what it meant to be a warrior. It is a philosophy of beautiful, decisive finality in a world often messy, complicated, and inconclusive. That idealized image of the samurai—loyal to the point of death, calm in the face of annihilation, finding freedom through letting go of life—was so powerful that it outlived the samurai class itself. It was revived, reinterpreted, and distorted through the centuries, eventually becoming a global cultural export via Japan’s modern storytelling. So when you see an anime hero summoning their second wind against an impossible foe, you aren’t witnessing a historically accurate depiction of a feudal warrior. You’re seeing the enduring spirit of Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s philosophy. You’re witnessing the power of an idea, an aesthetic of death born in the quiet shadows of leaves during a long, peaceful summer, which has somehow outlasted the very warriors it sought to define.