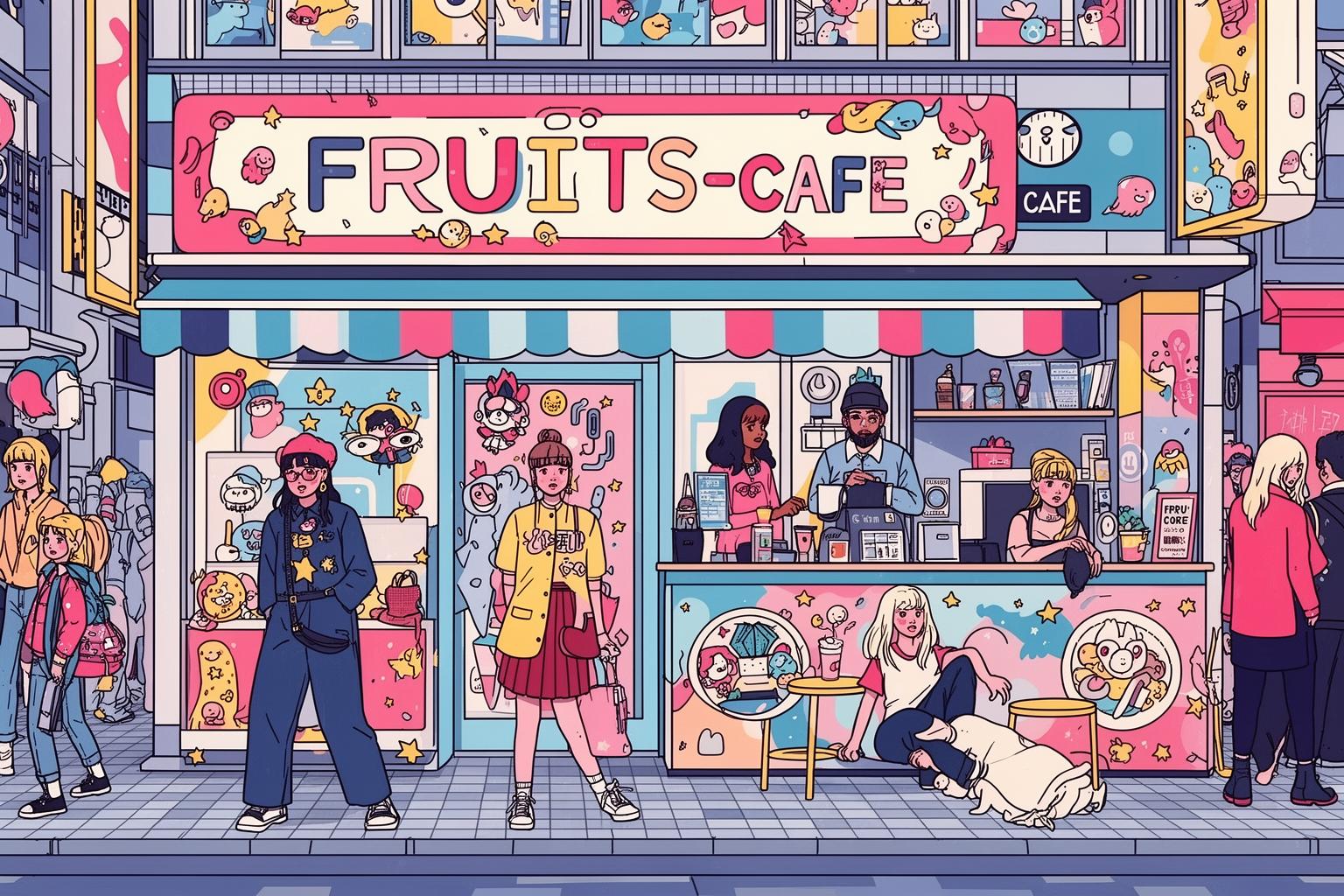

You’ve seen the pics, for sure. The explosive, retina-burning colors, the layers upon layers of mismatched chaos, the sheer, unapologetic weirdness of Harajuku street style from back in the day. Maybe you stumbled upon a dog-eared copy of ‘FRUiTS’ magazine in a vintage shop or scrolled past a mood board dedicated to the Decora and Ganguro kids of the late ’90s and early 2000s. It was a whole vibe, a legendary moment in fashion history that put this little Tokyo neighborhood on the global map. So you book a flight, you make the pilgrimage to Takeshita Street, ready to dive headfirst into that creative anarchy, and… it’s… different. It’s cute, don’t get me wrong. There are crepes, rainbow cotton candy, and endless stores selling idol merch and Korean cosmetics. But that raw, DIY, almost confrontational energy you saw in the photos? It feels a little… muted. A little more commercial, a little less chaotic. It leaves you with a major question: Where did the spirit of ‘FRUiTS’ actually go? Did it just up and vanish, a victim of its own success, replaced by fast fashion and global trends? Or did it just evolve, finding new, maybe less obvious, places to thrive? That’s the real tea. The truth is, that spirit didn’t die; it went inside. It found refuge from the commercialized streets and the tourist cameras in a new kind of sanctuary: the themed cafe. These spots are more than just places to grab a photogenic parfait. They are the spiritual successors to the street corner hangouts of the Y2K era, modern-day clubhouses where the ethos of self-expression, community, and obsessive detail is the main thing on the menu. To understand them is to understand the soul of Harajuku itself—not just what it looks like, but why it is the way it is. This isn’t a hunt for a perfect replica of the past. It’s a deep dive into how that iconic Y2K energy has been remixed and re-imagined for the 21st century, one meticulously crafted cream soda at a time. Let’s get into it.

To truly appreciate this meticulous craft, you need to understand the broader context of Japan’s kodawari cafe culture.

The Ghost in the Machine: What Was ‘FRUiTS’ Magazine, Anyway?

To understand why certain cafes today evoke a sense of stepping back into the Y2K era, you first need to grasp what ‘FRUiTS’ magazine truly embodied. It’s easy to glance at the photos now and simply admire the cool, retro outfits. However, from its debut in 1997 until it stopped publishing in 2017, ‘FRUiTS’ was doing much more than just chronicling fashion. It was capturing the pulse of a youth-driven cultural uprising, serving as a visual journal of a generation striving to find its voice in a country that seemed lost.

More Than Just a Lookbook

Context is everything here. The 1990s in Japan are widely known as the “Lost Decade.” The incredible economic boom of the ’80s—the “Bubble Era”—had spectacularly collapsed. The promise of lifetime employment, stable corporate jobs, a home, and family, which had long been the foundation of Japanese society, suddenly vanished. For the young people coming of age during this period, following their parents’ path was no longer viable. The system felt broken. So what do you do when the game is rigged? You upend the board and create your own rules. This economic anxiety and disillusionment provided fertile ground for a vast countercultural explosion. If society wouldn’t hand them a ready-made identity, they would build their own from scratch. Harajuku became their workshop and stage. ‘FRUiTS’, founded by photographer Shoichi Aoki, became their manifesto. Aoki didn’t direct or style his subjects; he simply wandered the streets and captured them as they were, in their natural environments. This was revolutionary. It wasn’t about high-fashion labels or professional models. It was about real kids, using whatever they could find—vintage clothes from thrift shops, handmade accessories, even household items—to craft intricate, deeply personal identities. It was a potent message: our worth lies not in what we can buy, but in what we can create. The style directly rejected the sleek, brand-obsessed consumerism of the Bubble Era and the dull, conformist uniformity of the corporate world. It was messy, colorful, and vividly human.

The ‘Harajuku Kid’ as a Social Statement

It’s essential to recognize that these styles were more than just costumes. They were visual languages for entire subcultures, each with its own philosophy and values. They were tribes. Take Decora, for example, with its explosion of plastic toys, stickers, and layers of neon pink, which was a bold challenge to the Japanese minimalist aesthetic of ‘wabi-sabi’ (finding beauty in imperfection and impermanence). It embraced joyful excess, creating a protective armor of cuteness against a bleak world. It declared, “I will not be quiet, I will not be subtle, I will be a walking celebration of happiness.” Then there was Visual Kei, which drew from glam rock and goth styles to create androgynous, theatrical personas that questioned traditional notions of masculinity. Or Lolita, which wasn’t about being sexy or childish, but about escaping into a hyper-feminine, doll-like fantasy inspired by Victorian and Rococo aesthetics. It rejected contemporary societal expectations of women, crafting a self-contained realm of elegance and grace. Importantly, all of this predated social media. The performance was not for an online audience or likes—but for validation from peers, from the other kids gathering on Jingu Bashi (the bridge linking Harajuku station to Meiji Shrine) on Sundays. You dressed up to be seen and acknowledged by your tribe. It was about physical presence and community in a very real and tangible way. This distinction is crucial to understanding the upcoming cultural shift.

The Caffeine-Fueled Clubhouse: Why Cafes Became the New Street Corner

The Harajuku you see today is the result of significant shifts that transformed how these subcultures could thrive. The raw, open-air stage where the ‘FRUiTS’ kids showcased their identities was gradually dismantled, pushing that creative energy to find new outlets. Cafes, with their distinctive role in Japanese social life, emerged as the ideal successors of that spirit.

From Pedestrian Paradise to Commercial Powerhouse

A major catalyst for change was the closure of ‘Hokoten’ (short for Hokousha Tengoku, or ‘pedestrian paradise’) in 1998. Every Sunday, a large stretch of road near Yoyogi Park was closed off to traffic, turning into an enormous open-air festival. Rockabilly dancers practiced their routines, Visual Kei bands put on impromptu gigs, and fashion tribes gathered to display their latest looks. It was the heart of Harajuku’s social life. When the city shut it down, citing traffic and safety concerns, it dealt a severe blow. The central meeting spot vanished. At the same time, Harajuku’s global fame skyrocketed in the 2000s. International fast-fashion giants like H&M, Zara, and Forever 21 opened massive flagship stores along the main streets. Rents soared, forcing out the small, independent vintage shops and indie brands that had fueled the DIY scene. Takeshita Street shifted from being a subcultural hub to a tourist hotspot. The indie spirit was effectively priced out. Then came the internet. The rise of blogs and later social media platforms such as Instagram radically changed the landscape. No longer did you have to be physically in Harajuku to see and be seen. You could curate your identity online, connect with your tribe through digital forums, and gain validation from a global audience. The need for a physical street corner diminished, replaced by the endless scroll of a feed.

The ‘Third Place’ Philosophy in a Japanese Context

So, where did all that energy go? It moved indoors, into what sociologist Ray Oldenburg called the “third place.” This concept refers to a place that is neither your home (the first place) nor your work or school (the second place). It’s a public setting that encourages community and creative interaction. In the West, this might be a pub, a park, or a coffee shop. In Japan, the idea of the third place is essential but operates somewhat differently. Japanese homes are often small, and there is a strong cultural divide between private life (uchi) and public life (soto). Inviting friends over is less common than in many Western cultures. As a result, neutral, public spaces where people can socialize, unwind, and express themselves are crucial. Cafes, especially in a dense city like Tokyo, became the perfect third place. But these aren’t ordinary cafes. They are highly themed, carefully curated environments. A themed cafe offers more than just coffee; it provides a temporary membership to a particular world. For the price of a drink, you can enter a space that reflects and legitimizes your chosen identity. It’s a controlled, safe environment. If you’re dressed in full Lolita fashion, you might attract stares on the subway, but in a cafe styled like a French parlor, you’re not just accepted; you belong. You become part of the décor. These cafes became the new clubhouses, the new street corners where identity performance continues in a more protected, intimate, and commercially viable manner.

Reading the Vibe: How to Spot a “FRUiTS-Core” Cafe

So, when wandering through the backstreets of Ura-Harajuku, how can you tell a truly ‘FRUiTS-core’ cafe apart from a generic, Instagram-famous tourist trap? It’s a nuanced skill. The vibe isn’t just about plastering neon signs on a pink wall. It’s rooted in a deeper philosophy that directly connects to the core principles of the street style era. You need to learn how to interpret the cultural signals.

It’s More Than Pink Walls and Neon Signs

There are three essential elements that define these spaces, extending far beyond surface-level visuals. They embody deeply ingrained Japanese cultural values, reimagined through a Y2K lens.

Element 1: Kodawari Taken to the Extreme

Kodawari (こだわり) is a Japanese term that’s famously hard to translate. It refers to an obsessive, uncompromising dedication to detail and craftsmanship. It’s the pursuit of perfection with intense personal passion. While you might encounter kodawari in a master sushi chef’s blade or the minimalist layout of a Zen garden, in a ‘FRUiTS-core’ cafe, it manifests as maximalism. Every single feature in the space is intentional, designed to create a cohesive, immersive world. From the font on the menu, to the shape of the ice cubes, the exact pastel shade on the straws, or the carefully curated playlist of obscure 90s Shibuya-kei pop—nothing is random. This is the opposite of a sterile, mass-produced setting. It’s a world crafted by someone obsessed, someone who has poured their soul into constructing a complete sensory experience. This meticulous world-building echoes the same impulse that drove a ‘FRUiTS’ kid to hand-sew patches on a jacket for weeks or arrange dozens of hair clips just so. It’s the art of obsession.

Element 2: Community as Part of the Decor

A genuine ‘FRUiTS-core’ cafe feels less like a commercial space and more like a clubhouse. A clear sign is how it engages with its community. Look around: are the walls adorned with art from local, unknown artists? Is there a small shelf selling zines, handmade accessories, or stickers by local creators? Do they host events, workshops, or pop-ups? Often, the staff actively participate in the subculture the cafe embodies. They aren’t just uniformed employees; their personal style forms part of the cafe’s identity. This fosters an atmosphere that’s collaborative and lived-in. It directly reflects the DIY, peer-to-peer spirit of the ‘FRUiTS’ era, where style and culture were generated and shared within the community, not dictated by big brands. The cafe becomes a physical hub for a network of creators, a living gallery for the scene.

Element 3: Consumption as Performance

In these cafes, food and drink are rarely just sustenance. They’re props in the performance of your identity. Ordering a towering parfait with ten colorful layers, or a vivid blue cream soda topped with a perfect scoop of vanilla ice cream and a cherry, becomes an interactive experience. It’s an edible work of art. The act of ordering, photographing, and eating these striking creations is part of the enjoyment. It sparks conversation, serves as a social ritual, and extends your personal aesthetic. Your drink transforms into an accessory complementing your outfit. This performative dimension is a direct evolution of street style. On Harajuku’s streets in the 90s, your outfit was your statement. In 2020s cafes, your order becomes part of that statement. It’s a way to engage with the cafe’s curated world and become a piece of the artwork yourself.

Case Study: The Kawaii Monster Cafe (and Its Legacy)

To grasp this philosophy pushed to its extremes, we need to discuss the legendary, now-closed Kawaii Monster Cafe. Opened in 2015 and designed by Sebastian Masuda, a true Harajuku kawaii icon, this venue was less a cafe and more a psychedelic dive into kawaii’s subconscious. It featured a rotating cake-shaped merry-go-round, mushroom-themed disco rooms, and waitresses (the “Monster Girls”) clad in wildly conceptual outfits. The food was outrageously colorful and deconstructed. It was the ultimate example of the cafe as an immersive theme park. Its closure in 2021 marked the end of an era. Yet its influence is profound. It proved there was a strong appetite for high-concept, experiential spaces. However, its massive scale also made it fragile. The Monster Cafe’s spirit now thrives in smaller, more nimble, and arguably more authentic venues. The scene took a vital lesson: the future lies not in one giant, tourist-centric spectacle, but in a network of smaller, community-focused hubs.

The Modern Sanctuaries: Where to Find the Y2K Spirit Now

So, let’s get specific. Where can you actually find these places that embody the ‘FRUiTS’ spirit? These aren’t merely cafes; they serve as living case studies in Japanese subculture, each providing a unique perspective on the evolution of Harajuku’s creative essence.

Cafe 1: Design Festa Cafe & Bar – The Embodiment of the DIY Ethos

If you want to experience the raw, untamed spirit of Harajuku’s creative community, your first stop must be the Design Festa Cafe. This spot isn’t Y2K aesthetic in the typical sense—it’s not all pink and glitter. Instead, it captures the process and philosophy of the ‘FRUiTS’ era more authentically than anywhere else. Operated by the same team behind the large-scale Design Festa art event, this cafe functions as a year-round gallery and social hub for Tokyo’s independent creators. Its interior is a chaotic, ever-changing explosion of art, with walls covered floor to ceiling in paintings, illustrations, and mixed-media pieces by hundreds of diverse artists. Every piece is for sale, and the exhibition continuously evolves. It’s a living, breathing creative organism.

The Connection: This is the 21st-century ‘Hokoten.’ An indoor, weatherproof version of the former pedestrian paradise, it’s where artists and designers gather to meet, share ideas, collaborate, and, most importantly, showcase their work to an engaged audience. The focus here isn’t a singular, polished aesthetic but the vibrant diversity and energy of individual expression. It’s messy, eclectic, and genuinely authentic. Just as Shoichi Aoki’s camera in ‘FRUiTS’ celebrated unique individuals over dominant trends, the Design Festa Cafe honors the artist rather than the aesthetic. It’s a space founded on the belief that everyone has something creative to offer.

What it tells us: Harajuku’s creative energy hasn’t died; it’s simply evolved and organized. It has found a permanent home where it can thrive and be monetized in a way that directly supports its community. The scene now emphasizes sustainability over rebellion—a reflection of how a spontaneous street culture matures into an enduring cultural institution.

Cafe 2: Caroline Diner – American Nostalgia Through a Japanese Perspective

When you step into Caroline Diner, you are instantly transported—to where exactly? It resembles a 1950s American diner, but it’s… too perfect. The turquoise is excessively bright, the red vinyl too glossy, and the neon signs glow with an almost otherworldly intensity. This café isn’t a mere replication of an American diner; it’s a stylized fantasy—an idealized diner filtered through a hyper-stylized Japanese lens. Their signature cream sodas—glowing, jewel-toned blends of melon, strawberry, and blue curaçao topped with immaculate scoops of vanilla ice cream—are liquid sculptures crafted to be photographed.

The Connection: This cafe masterfully exemplifies the Japanese cultural practice of mitate (見立て), the art of reinterpretation or seeing one thing as an analogue of another. During the Y2K era, Harajuku fashion revolved around mitate, with youths deconstructing Western subcultures—punk, goth, hip-hop—taking visual elements they liked and reassembling them into something entirely new and distinctly Japanese. Caroline Diner applies this same creative process to Americana. It’s unconcerned with the greasy reality of a 50s diner but captivated by its idea, its aesthetic essence, which it then exaggerates and perfects. It evokes nostalgia for a time and place that never truly existed, a shared daydream fueled by movies and pop culture. The cream soda serves as the perfect metaphor: a simple, classic American drink transformed into a high-concept work of kawaii art.

What it tells us: The global influences that shaped Y2K Harajuku style remain potent. However, it’s never a direct imitation; rather, it’s an ongoing cycle of absorption, translation, and reinvention. This café demonstrates how Japanese culture can take an external influence and refine it into an aesthetic purity the original never achieved. It’s a celebration of surface, and in Harajuku, surface always contains depth.

Cafe 3: Mipig Cafe – The Unlikely Successors of Kawaii Maximalism

At first glance, an animal cafe—especially one featuring adorable micro pigs—may seem unrelated to Y2K street fashion. But looking deeper, the cultural impulse connecting them becomes clear. Upon entering Mipig Cafe, you are instantly enveloped by a powerful force: cuteness. The space is soft and gentle in color, with tiny, well-mannered pigs wandering freely, ready for cuddling. The whole experience is designed as a concentrated, high-impact dose of kawaii.

The Connection: Recall the Decora style captured in ‘FRUiTS’, which was about creating a personal joy bubble by physically surrounding oneself with overwhelming quantities of cute objects—plastic hair clips, cartoon character bandages, plush keychains—as a kind of aesthetic armor. Animal cafes represent the modern, experiential evolution of this impulse. Instead of wearing cuteness, you immerse yourself in it. For a fixed period, you can escape the stress and complexity of the real world and enter a simplified reality governed by kawaii logic. The pigs act as living, breathing accessories to this immersive experience. The longing for a temporary escape into a fantasy realm mirrors the desires that fueled Lolita and Decora subcultures.

What it tells us: The idea of a subcultural “third place” has expanded and become more experiential. It’s no longer just about shared fashion sense but shared curated experiences. The commodification of cuteness has reached its logical end: you can now pay to interact with it physically. While this may feel more commercialized than the DIY street style of the past, the core psychological need it satisfies—a safe, cute, joyful escape—remains unchanged.

The Takeaway: Is It Real or Just for the ‘Gram?

Alright, let’s tackle the big, skeptical question looming over all of this. Many of these carefully designed cafes and perfectly photogenic cream sodas seem as if they were made just for Instagram. Are these spaces truly nurturing community and self-expression, or are they merely elaborate sets for social media posts? The honest answer is: they’re both. And that’s not inherently negative.

The Double-Edged Sword of Social Media

There’s no denying that the rise of visual social media platforms has significantly influenced these spaces. The urge to capture and share a unique aesthetic experience plays a huge role in their appeal. But dismissing them as “inauthentic” misses the point. In the era of ‘FRUiTS,’ the performance was for the street and for Aoki’s camera. Today, the street is global and digital. The platform has changed, but the basic human desire to shape identity, perform for an audience, and find your tribe remains the same. Social media is simply the modern stage for the same drama. The real risk isn’t that these spaces are photogenic. The risk emerges when the algorithm’s logic begins to dictate culture. Social media often favors aesthetics that are easily digestible, conventionally attractive, and trend-driven. This can lead to a homogenization of style, where the truly strange, challenging, and wonderfully ugly experiments that made the pages of ‘FRUiTS’ so thrilling might be filtered out in favor of what’s likely to get likes. The pressure to be “aesthetic” can sometimes suppress the drive to be genuinely original.

How to Experience it “Correctly”

So, if you’re exploring these spaces, my advice is to change your mindset. Don’t enter with a checklist, merely hunting for the perfect photo for your feed. Enter as a cultural observer. See these cafes not as mere backdrops, but as stages, and pay attention to the performance taking place on them. Notice the kodawari—the tiny, obsessive details the creator has poured their soul into. Observe other customers. Are they all tourists, or are there regulars—people who genuinely use this as their third place? Are they engaging with each other, or just glued to their phones? Listen to the sounds, soak in the atmosphere. Realize you’re stepping into a meticulously crafted world. The goal isn’t to find the “real,” gritty Harajuku of 1998 frozen in time. That Harajuku no longer exists. The goal is to understand why these curated, fantasy-like spaces are so essential and appealing in today’s Japan. They are the logical—and perhaps inevitable—evolution of that raw street energy, now professionally packaged for a new generation with new tools and a new kind of stage. The spirit of ‘FRUiTS’ was never about a single look. It was about the passionate, joyful, and sometimes deeply strange dedication to creating your own world amid a confusing one. And in the quiet, colorful corners of Harajuku’s backstreets, for the price of a stunning soda, you can still rent a little piece of that world for an hour or two. It’s not gone—it’s just different. And that’s totally cool. Maji de.