Yo, let’s be real. You’ve seen it. That big, yellow, polka-dotted pumpkin sitting serenely on a pier, waves lapping at its feet. It’s the unofficial mascot of Naoshima, an island that’s blown up on every aesthetic travel feed for the last decade. It’s the kind of pic that makes you think, “Okay, I need to go there.” But then the questions start bubbling up. Why is all this world-class, ridiculously expensive art on this tiny, remote island in the middle of Japan’s Seto Inland Sea? And what’s the deal with all the other buildings? All that stark, gray concrete by this famous architect, Tadao Ando. In photos, it can look kinda… intense. A little cold, maybe even brutalist. Is a trip all the way out there really worth it for a pumpkin pic and a tour of some concrete bunkers? It feels like there’s a major piece of the story missing between the Instagram posts and the reality of booking ferries and crazy-expensive museum tickets. What’s the actual vibe? If you’re wondering whether Naoshima is just a hyper-curated tourist trap or a legit cultural pilgrimage, you’re asking the right questions. The whole island is way deeper than a single piece of art. It’s a statement, a massive, decades-long project about rebirth, nature, and the power of space. So, let’s get into it, let’s spill the tea on why this island of concrete and contemporary art is one of the most essential cultural experiences in Japan. It’s a journey that’s designed to mess with your perceptions, slow you down, and make you see the world, or at least a patch of sky, in a totally different way.

To truly understand Ando’s mastery of space and light on Naoshima, it helps to see how his work connects to broader Japanese architectural principles like the engawa.

The Island’s Glow-Up: From Industrial Afterthought to Art Sanctuary

To truly understand Naoshima, you need to travel back in time. This island wasn’t always known as a trendy art destination. Quite the opposite. The transformation from a neglected industrial center to a world-renowned art hotspot lies at the heart of its story—a tale of remarkable vision and bold optimism. It’s an extraordinary makeover that completely changes how you experience the art and architecture scattered throughout its hills.

The Setouchi Story: A Sea of Fading Dreams

The Seto Inland Sea, where Naoshima is located, is stunningly beautiful. With over 3,000 islands, it has been an essential waterway for centuries. Yet by the latter half of the 20th century, this idyllic setting concealed a grim reality. The region powered Japan’s post-war industrial growth. Islands such as Naoshima hosted refineries, quarries, and processing plants. For many years, industry meant jobs and prosperity. But economic changes and the relocation of heavy industries weakened this foundation. For example, northern Naoshima was home to a large Mitsubishi materials refinery, which provided employment but also caused environmental harm. The islands of the Seto Inland Sea faced three major challenges: economic decline, environmental damage from industrial waste, and a significant population loss as young residents moved to cities like Tokyo and Osaka. The islands were being hollowed out, both literally and figuratively, left with aging populations and the remnants of a fading industrial age. They were becoming places people abandoned rather than visited. This background is vital. Naoshima wasn’t a pristine, untouched paradise waiting to be found; it was a community in need of renewal, searching for a new identity.

Enter Benesse: The Visionary Art Patron

Here the story takes an unexpected turn. In the late 1980s, Soichiro Fukutake, head of the Benesse Corporation (a large education and publishing company), had a visionary idea. Together with Naoshima’s then-mayor, Chikatsugu Miyake, he imagined a future not centered on restoring industry but on reviving the island’s spirit through art and architecture. This was not a commercial venture aimed at quick profits. It was a deeply philosophical, long-term mission. Their guiding principle became: “Using what exists to create what is to be.” Rather than erasing the island’s industrial past or natural environment, they sought to engage with it. They invited the internationally acclaimed, self-taught architect Tadao Ando to bring this vision to life. The first project, a combined hotel and museum known as Benesse House, was merely the start. The core concept was revolutionary: art should not be limited to sterile galleries in big cities. It could be woven into nature and community, becoming a catalyst for social and economic renewal. This was a bold gamble on the belief that creating a place of profound beauty and intellectual richness could reverse decades of decline and give a forgotten island a new purpose.

Tadao Ando’s Concrete Poetry: Not Your Average Brutalism

Alright, let’s delve into the concrete. At first glance, images of Tadao Ando’s work on Naoshima—the Chichu Art Museum, Benesse House—can feel imposing. They showcase clean lines, sharp angles, and vast walls of plain, gray concrete. The term “brutalist” might come to mind, evoking thoughts of cold, monolithic structures. But to categorize Ando’s work this way completely misses the essence. In Japan, he’s revered not as a creator of brutal buildings, but as a poet who speaks through concrete. His architecture isn’t meant to dominate the landscape; rather, it creates a quiet space for dialogue with it. He designs buildings that focus less on the structures themselves and more on the experience they craft for the people inside.

The Ando Philosophy: Light, Shadow, and Nature

To truly understand Ando, you must grasp his trinity: concrete, light, and nature. He perceives these elements as engaging in a continuous, dynamic interaction. His brilliance lies in how skillfully he shapes and controls this interplay.

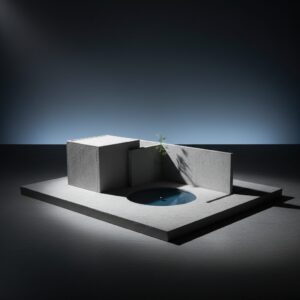

Concrete as a Canvas

Firstly, the concrete he uses is unlike any you might have seen or touched before. Ando has perfected a formula and formwork technique resulting in a surface that is unbelievably smooth—almost velvety—with a calm, consistent gray tone. The circular tie holes left from construction are arranged with geometric precision, serving as subtle, rhythmic decoration. This isn’t rough, industrial concrete; it’s a refined, almost sacred material. He treats it like a neutral canvas—quiet and unobtrusive, fading into the background so the true stars can shine. What are those stars? Light and shadow. As the sun moves through the sky, light streams through carefully placed slits and openings, casting shifting patterns and dramatic shadows on the smooth gray walls. The concrete becomes a screen that projects the passage of time and the atmosphere of the day. The building feels alive, breathing in tune with the natural world.

Borrowed Scenery (Shakkei)

Ando’s work is deeply grounded in traditional Japanese aesthetics, particularly the principle of shakkei, or “borrowed scenery.” This is the art of integrating the surrounding landscape into the design of a building or garden, making it a fundamental part of the view from within. Ando is a master at this. His structures on Naoshima don’t arrogantly perch on the hills; they are often nestled into or even partially buried within them. He creates vast floor-to-ceiling windows, open courtyards, and long ramps that offer more than just a pleasant view; they frame the sea, sky, and green hills as if they were living paintings. The architecture compels you to see nature anew, with intention. A simple window transforms into a curated frame, turning a patch of blue sky or a wind-swept tree into a masterpiece. He isn’t building against nature; he is building with nature.

The Journey is the Destination

Visiting an Ando building is never about simply entering and seeing one main feature. He designs his spaces as a sequence, a procession. You are led through long, sometimes disorienting corridors of bare concrete, where your footsteps echo and your sense of direction dampens. These paths are meant to cleanse your mental palate, stripping away the noise of the outside world. Then, all at once, you turn a corner and are met with a soaring, open-air courtyard flooded with light or a vast window framing a breathtaking view of the Seto Inland Sea. This contrast—between enclosure and openness, darkness and illumination—is a powerful emotional device. He choreographs your experience, encouraging you to slow down, be fully present, and savor the transition from one space to the next. The journey through the building is as significant, if not more so, than the destination itself.

The Pilgrimage Sites: Experiencing Ando’s Vision IRL

A trip to Naoshima is not a checklist tour; it’s a pilgrimage. Each of Ando’s major works on the island serves as a distinct kind of temple, offering a unique reflection on the relationship between art, architecture, and the natural world. To truly experience their impact, you must fully surrender to the experience they demand.

Benesse House Museum: Where Art and Life Blur

This was the beginning of it all, the first major project. Its concept remains astonishing: it’s a world-class contemporary art museum where you can also spend the night. The boundary between visitor and resident, between observing art and living alongside it, completely dissolves. The architecture itself is a lesson in harmony. The main museum building is not placed on the coastline; it is built into a hill overlooking the sea, with a long, curving form that follows the natural contours of the land. Large portions of the structure are open to the elements, with ramps and walkways exposed to the sea breeze. Inside, enormous windows frame the ocean like vast, ever-changing canvases. At one moment, you might be gazing at a complex piece by German artist Anselm Kiefer, then turn your head to see a ferry silently gliding across the water. The art extends beyond the galleries, spilling out onto the surrounding grounds and along the coast—the iconic yellow pumpkin by Yayoi Kusama is part of this collection. Staying here is an immersive experience. Waking up and strolling through the galleries in your pajamas before the day visitors arrive is an unmatched privilege. It perfectly fulfills the Benesse goal of merging art with life. It feels less like staying in a hotel and more like being a guest in an exquisitely curated home, where nature is always invited inside.

Chichu Art Museum: Hidden Treasure and Divine Light

If Benesse House is the foundation, Chichu is the crown jewel. Without exaggeration, it is one of the most profound architectural and artistic experiences anywhere in the world. The name “Chichu” means “in the earth,” and that’s exactly what it is. To preserve the stunning natural coastal scenery, Ando boldly decided to bury the entire museum underground. From above, all you see are geometric openings—squares, rectangles, triangles—cut into the green hilltop. This single gesture speaks volumes about the project’s philosophy: architecture must serve nature, not dominate it. The experience begins as you walk up a quiet path flanked by a garden inspired by Monet’s own at Giverny. Then you descend into a world of bare concrete. The entire museum is illuminated solely by natural light filtering through dramatic openings in the ceiling. The quality of the light shifts constantly depending on the time of day, weather, and season, ensuring the art and space are never the same twice. The museum was designed to permanently house the work of only three artists, with Ando creating a unique sanctuary tailored to each.

Claude Monet’s Sanctuary

You enter a luminous white room with gently rounded corners. The floor is composed of thousands of tiny marble cubes that soften your footsteps. Bathed in diffuse, heavenly light from an unseen source above, five of Monet’s late “Water Lilies” paintings hang on the walls. Seeing them here, apart from the gilded frames and formal halls of a traditional European museum, is revelatory. The natural light allows the colors in the canvases to breathe and shift. Ando has fashioned a space of pure contemplation, a secular chapel where Monet’s vision of light and water is experienced with exceptional clarity and serenity.

Walter De Maria’s Temple

You move up a grand staircase into a vast, cathedral-like hall. At its center sits a huge, 2.2-meter polished granite sphere. On the walls hang 27 gilded wooden sculptures arranged in geometric patterns. The entire space is illuminated by a long skylight running the length of the ceiling, casting a sharp, moving shaft of light across the room. As the sun moves, the light interacts with the sphere and golden sculptures, marking the passage of time. The piece, titled “Time/Timeless/No Time,” becomes tangible through Ando’s architecture. You sense the earth’s rotation in the slow movement of light. It is an awe-inspiring space, both ancient and futuristic in feel.

James Turrell’s Perception Game

James Turrell is an artist who uses light itself as his medium. For “Open Sky,” you enter a square room with a bench along the walls. You sit down and look upwards. The ceiling is gone, replaced by a perfectly sharp-edged rectangle of open sky. That’s it. Yet, as you sit, your perception begins to shift. The sky, framed so precisely by the architecture, no longer appears as empty space but as a solid, flat plane of color. Clouds drift across like brushstrokes. At dusk, hidden LEDs subtly alter the wall colors, dramatically changing your perception of the sky’s hue. It’s a hypnotic, meditative experience that invites you to just sit, look, and be present. The no-photography rule here, and throughout Chichu, is essential to the experience. It’s a challenge, yes, but a necessary one that compels engagement with the art through your own senses rather than through a phone lens. It’s a soul-level vibe check.

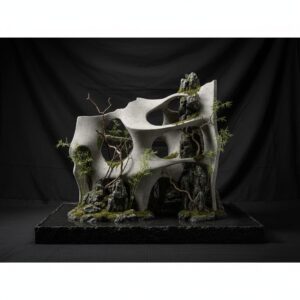

Lee Ufan Museum: The Art of Doing Less

A collaboration between Ando and Korean artist Lee Ufan, this semi-underground museum is a masterclass in minimalism. Lee Ufan was a key figure in the Mono-ha (“School of Things”) movement, a Japanese art movement from the late 1960s focusing on the relationships between natural and man-made materials. His art often features simple arrangements of stone, steel plates, wood, and paper. The philosophy centers on presence, encounter, and the importance of empty space, or yohaku. Ando’s architecture perfectly complements this, creating a series of stark, powerful concrete spaces—a long, narrow corridor leading to a single stone and its shadow; a triangular courtyard with a rock and a steel plate. The building fosters a quiet, contemplative dialogue between the raw materials of the art and the refined materiality of the architecture. It’s a space that invites you to slow down and appreciate the profound beauty in simplicity. The empty space is as imbued with meaning as the objects themselves, embodying the idea that less truly is profoundly more.

Ando Museum: A Concrete Matryoshka Doll

Located in Honmura, a charming village of traditional wooden houses, the Ando Museum is one of his most clever and intimate projects on the island. Here, he took a 100-year-old traditional Japanese house, or minka, and carefully inserted a completely new concrete structure inside its original wooden shell. This perfectly expresses the philosophy of “Using what exists to create what is to come.” From outside, it looks like a beautifully preserved old house, but inside, intersecting planes of light and shadow unfold in dialogue between the warm, dark wood of the old house and the cool, pale gray concrete interior. It’s like a structural matryoshka doll. The museum is small, containing models, sketches, and drawings of Ando’s work on Naoshima. It offers a journey into his mind, revealing how he approached the challenge of building on this island. The tension and harmony between old and new, tradition and modernity, is central. It’s a small space that tells a very large story.

The Reality Check: Is the Pilgrimage Worth It?

So, after everything, what’s the true story? Is Naoshima an essential, transformative art experience, or is it an overhyped, costly, and somewhat inconvenient spot? The honest truth is: it can be both. It all hinges on your expectations and mindset. Let’s be upfront about the possible drawbacks.

The Instagram Hype vs. The Actual Atmosphere

Thanks to its huge social media popularity, Naoshima is no longer a hidden gem. It can get quite crowded, especially during peak times. You absolutely need to reserve tickets for the Chichu Art Museum, sometimes months ahead. Timed entry slots fill rapidly. You’ll probably have to wait in line to photograph the yellow pumpkin. If your main aim is to quickly grab iconic shots for your feed, the crowds and strict no-photography policies in major museums might frustrate you. But here’s where the island’s philosophy becomes clear. The rules exist for good reason. They are an invitation—or perhaps a demand—to put your phone down and engage directly with the art and architecture. The real essence of Naoshima isn’t about creating content; it’s about being present. If you can accept that, the crowds fade into the background, allowing your own personal experience to shine.

The Cost of Art

Let’s not kid ourselves: Naoshima is pricey. The ferry to reach the island, the bus or bike to get around, and admission fees for each museum all add up fast. A ticket to Chichu alone costs over 2,000 yen. Staying on the island, especially at the sought-after Benesse House, is a considerable expense. This isn’t a destination for the budget traveler. But it helps to see the cost differently. You’re not just paying for admission—you’re supporting the preservation of remarkable architecture, the conservation of art, and the sustainable economy of a community transformed by this project. You’re investing in the future of a bold, beautiful, and hopeful vision.

So, What’s the Bottom Line?

If you want a relaxed beach getaway with some cool photo opportunities, Naoshima may not be your best bet. It requires planning, and the experience calls for your full attention. It’s more active involvement than passive vacation. But if you’re even a little curious about the impact of art, the poetry of architecture, and the chance for renewal, then it’s an absolutely essential journey. It’s a place that rewards curiosity and patience. It asks you to walk, observe, rest, and feel. It’s a dialogue between past and future, man-made and natural, monumental and minimal. You’ll leave with a newfound appreciation for how a simple concrete wall can catch the light, or how a frame can shift your view of the sky. Naoshima isn’t just a place to see; it’s a place that works on you. And that, friends, is a transformation that can’t just be snapped for the ‘gram.