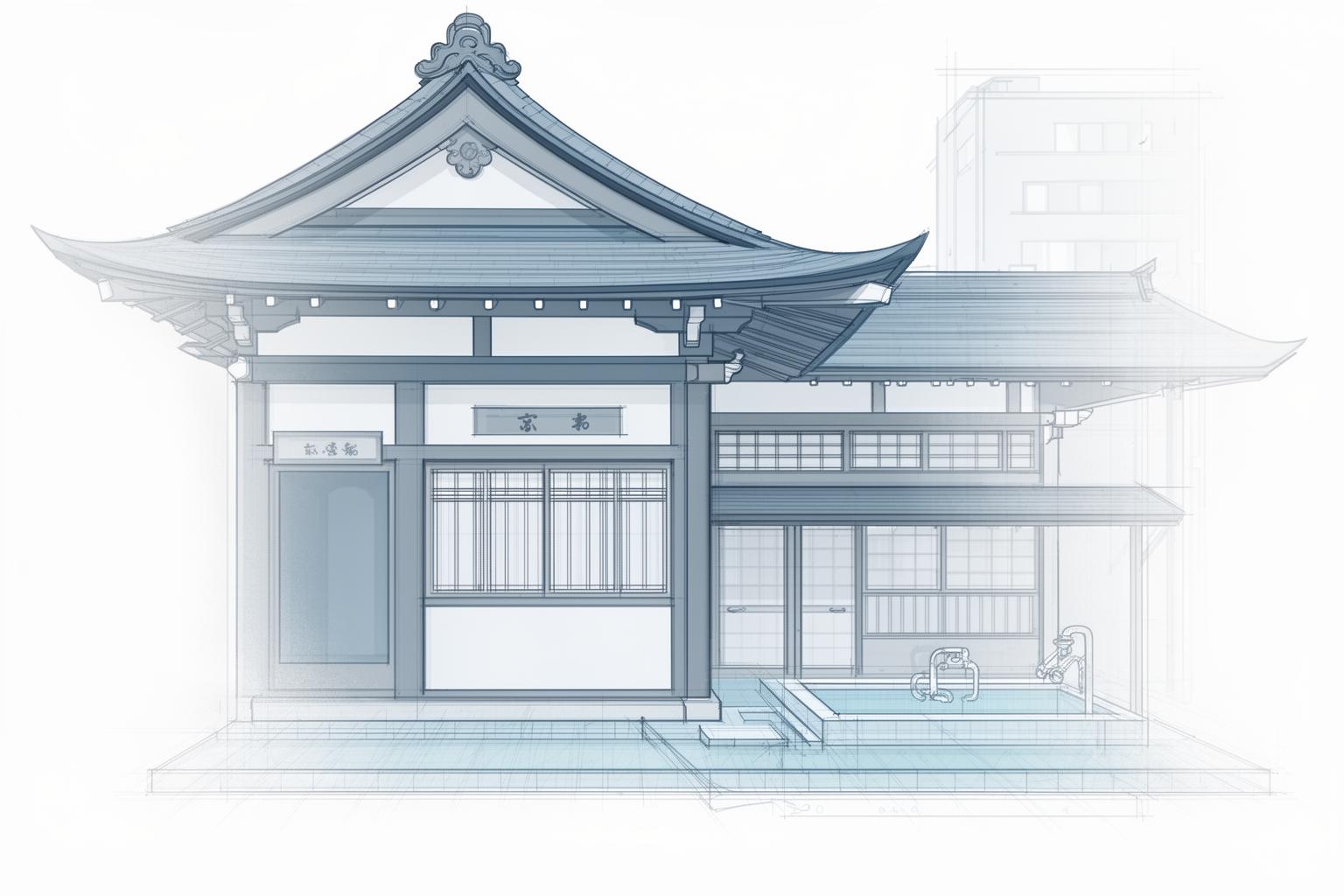

You’ve probably seen the pictures. A massive, painted mural of Mt. Fuji, steam rising from tiled pools, old-timers soaking with towels on their heads. This is the sentō, Japan’s public bathhouse. And if you’re scrolling through social media, it looks like a perfectly aesthetic, retro experience—a must-do for that authentic Japan trip. But let’s get real for a second. The question that hangs in the air, especially for anyone from a culture where public bathing isn’t the norm, is a simple one: why? Why did an entire society, for generations, build its daily routine around getting naked with neighbors when they could just… bathe at home? The answer is that the Showa-era (1926-1989) sentō was never really just about getting clean. That was the entry ticket, not the main event. The real deal was community. The sentō was the neighborhood’s living room, its newsroom, its therapist’s couch, and its daycare center, all rolled into one steamy, tile-covered package. It was a masterclass in social infrastructure, a place where the unwritten rules of Japanese society were learned and reinforced, a hub where connections were forged in a way that’s becoming almost impossible to imagine in today’s hyper-privatized world. But these vibrant hubs are fading, with dozens closing their doors every year. To understand modern Japan—its obsession with privacy, its shifting community structures, and its deep-seated nostalgia—you have to understand the rise and fall of the sentō. It’s a story about more than just architecture and hot water; it’s about the very soul of a neighborhood and the slow, inevitable tide of change. Before we dive deep, here’s a look at one of Tokyo’s most iconic surviving bathhouses, Daikoku-yu, a tangible piece of the era we’re about to explore.

This fading of community hubs mirrors a broader cultural nostalgia for the Showa era, a sentiment also powerfully evoked in the era’s music and city pop.

The Sentō Vibe: Not Just a Bath, But the Neighborhood’s Living Room

To truly understand the sentō, you need to rewind your mental image of Japan. Forget the sleek, high-tech country of today and instead imagine the Showa era, particularly the post-war decades of reconstruction and rapid economic growth. Cities like Tokyo and Osaka were sprawling, dense mosaics of low-rise wooden houses and small apartment buildings. A defining characteristic of these homes was what they lacked: a private bathroom. The uchiburo, or home bath, was a luxury. For most urban residents, bathing daily wasn’t a private ritual but a communal one. The sentō wasn’t just a choice; it was a fundamental necessity, as routine as buying groceries or collecting mail. This shared daily need became a powerful social anchor. Each evening, without fail, the entire neighborhood would head to the local sentō, which became the default third place—a neutral space between the cramped home and the demanding workplace.

Here is where the idea of hadaka no tsukiai—literally, “naked communion” or “naked relationship”—comes into focus, a concept essential to understanding Japanese social dynamics. At first glance, it might seem awkward. But its philosophy is profound. In a society as hierarchical and context-driven as Japan’s, where clothing, business cards, and posture all indicate status, the sentō was the great equalizer. Once you shed your work uniform or fine suit, you were simply another individual in the bath. The company president would be soaking next to the factory worker, the strict schoolteacher beside the local shopkeeper. All external signs of rank and wealth were left behind in the wooden lockers. This created a unique environment for candid communication. Conversations that would be impossible in a formal office setting happened naturally in the steamy water. People sought advice, shared gossip, vented about their bosses, and celebrated small victories with neighbors, all on equal footing. It fostered a deep, unspoken sense of solidarity and trust. You were, quite literally, seeing your neighbors at their most vulnerable, and they likewise saw you.

This dynamic made the sentō the real information hub of the community. Before social media and 24-hour news, there was the sentō. It was where news circulated—about a new store opening, whose child was getting married, who was sick and might need help, or the latest local political gossip. It was a living, breathing social network built from daily, face-to-face interactions. The sentō was also a classroom for life. Children, brought along by parents or grandparents, learned essential social etiquette by watching others. They absorbed how to wash properly before entering the main bath, to avoid splashing or making noise, and how to treat elders respectfully. They soaked in the subtle rhythms of community simply by being present. For the elderly, the sentō was a vital lifeline against isolation, offering daily social contact, a place to meet friends, and a way to feel part of the community’s ongoing life. The simple act of noticing when an elderly regular hadn’t shown up for a few days often prompted a welfare check that saved lives. The sentō wasn’t just a building; it was a deeply ingrained social safety net, built on the simple yet powerful foundation of a shared daily ritual.

The Anatomy of a Showa Sentō: A Masterclass in Ambiance

Showa-era sentō were more than just practical facilities; they were architectural masterpieces intended to transform the simple act of bathing into a daily moment of escape and even splendor. Their design was deliberate. Every detail, from the imposing roof to the tiny, colorful tiles, was carefully crafted to evoke a particular atmosphere—one of hospitality, imagination, and community pride. Entering a classic sentō was like stepping into another realm, a thoughtful and beautifully realized divergence from the often drab and crowded urban surroundings. These bathhouses were not merely places to bathe; they were secular sanctuaries devoted to the ritual of cleanliness and social connection.

The Façade: Temple Ambience and Inviting Lanterns

First impressions were crucial, and sentō builders knew how to create one. Many traditional bathhouses featured the miya-zukuri style, which means “shrine construction.” They boasted sweeping karahafu gables—ornate, curving rooflines reminiscent of castles or major temples. This was a bold architectural statement. It signaled to the neighborhood that the building was significant, a landmark and community cornerstone. Imagine the psychological impact: among simple wooden houses, the sentō stood out like a cathedral. This grandeur served a purpose, elevating the routine task of bathing into a dignified, almost sacred experience. It provided an accessible touch of luxury and visual delight to working-class patrons. Approaching the entrance, guests passed beneath a large noren curtain, usually displaying the bathhouse’s name and the hot water symbol (ゆ), accompanied by the cozy glow of lanterns. The entrance was designed as a warm welcome, clearly indicating that one was leaving the everyday world behind to enter a space of comfort and relaxation. Though a public facility, its design made it feel like a grand communal palace.

The Gateway: Bandai and the Separation by Gender

Upon entering, visitors found themselves in the datsuiba, or changing room. Yet the true command center of the sentō was the bandai: a raised platform resembling a throne or judge’s bench, positioned between the men’s and women’s changing areas. From this vantage point, the attendant—often an elder woman from the family that owned the sentō—oversaw everything. They collected fees, sold soap and towels, monitored the lockers, and most importantly, served as the neighborhood’s information hub. The bandai attendant knew everyone’s names, family situations, and all the latest news. They were gatekeepers, confidants, and community pillars. The changing rooms themselves offered a symphony of distinct sounds and textures—the clatter of wooden locker keys, creaking floorboards, and high vaulted ceilings with lattices for ventilation. A partial wall separated the men’s and women’s areas without reaching the ceiling, allowing sounds and steam to pass through, fostering a sense of shared communal experience despite the gender divide. This semi-public, semi-private space perfectly embodied the sentō’s role as a bridge between home and the outside world.

The Main Attraction: Mt. Fuji and the Art of Visual Escape

Opening the door to the bathing area revealed the true highlight. The air was thick with steam, the sound of splashing and conversation echoed off tiled walls, but the eyes immediately gravitated upward to the centerpiece: the penki-e mural. While other subjects existed, Mt. Fuji reigned supreme as sentō’s iconic artwork. Why Mt. Fuji? It is Japan’s most sacred and emblematic mountain, symbolizing national identity, beauty, and permanence. Its function in the sentō was also practical and clever. Most bathing rooms lacked windows to maintain privacy and heat, so the expansive Fuji mural created an illusion of openness and depth, a psychological trick to make the enclosed room feel endless. It was a form of mental escape, allowing bathers to imagine themselves in a majestic landscape while soaking in the hot water. These murals were painted by a small number of specialized artists—a fading craft—and were a point of pride for sentō owners. Beneath the mural, the space dazzled with intricate, colorful tiles—often Kutani-yaki or majolica styles—depicting carp, flowers, or geometric patterns. These tiles were not only decorative but also durable, waterproof, and easy to clean; their artistry elevated them beyond mere function. Coffered wooden ceilings (gōtenjō), borrowed from temple and castle architecture, added to the sense of grandeur. Every design aspect aimed to create a rich sensory experience, far removed from the straightforward utility of a modern bathroom.

The Details That Made a Difference

The charm of the Showa sentō also lay in the small, seemingly trivial details that together formed an unforgettable ritual. It was the feel of iconic yellow washbowls, produced by the company Kerorin, so ubiquitous they became a cultural emblem. Stamped with the company’s name, they were sturdy, stackable, and their bright color became synonymous with the sentō experience. It was the sound of the wooden getabako lockers clacking at the entrance. It was the old mechanical weighing scale in the changing room, sparking endless public banter and comparison. Perhaps most importantly, it was the post-bath tradition. After soaking until the skin turned pink and muscles relaxed, bathers headed to large glass-fronted refrigerators in the changing room. The beverage of choice was almost always milk—either plain or coffee-flavored—served in classic glass bottles with paper caps. Drinking that ice-cold milk, often with one hand resting on the hip, was the perfect, universally recognized finale to the experience. These were not random objects or habits, but sensory anchors of a powerful cultural ritual—small shared memories that connected generations of Japanese people.

The “Why” of the Decline: A Fading Blueprint

The golden age of the sentō was never meant to last indefinitely. The very forces that drove Japan’s post-war economic miracle eventually triggered the decline of the public bath. The story of why these once-vital community centers are now disappearing is fundamentally a story about modernization—about shifting priorities, advancing technology, and a profound change in the social fabric of neighborhood life. The sentō was an ideal solution for a specific era, but as that era passed, the model began to feel outdated. Its decline stemmed not from a single cause but from a convergence of significant social and economic pressures that transformed Japanese society at its core.

The Rise of the “Uchiburo” (Home Bath)

The most decisive factor behind the sentō’s decline is straightforward: the widespread adoption of the private home bath, the uchiburo. With Japan’s economy expanding from the 1960s onward, wages and living standards rose. Having a private bathroom with a bathtub and shower evolved from a luxury to a standard feature in new homes. The government encouraged this trend through public housing initiatives as well. Consequently, the sentō ceased to be an everyday necessity. Why venture out into the cold carrying soap and shampoo when you could enjoy bathing in the comfort and privacy of your own home at any time? The convenience was undeniable. The daily ritual, once a vital part of community life, was recast as a routine chore that could now be handled more efficiently at home. The sentō shifted from a practical necessity to a leisure choice—a place you could visit, not one you had to. This fundamental change marked the beginning of the end for thousands of local bathhouses.

Shifting Social Scripts

Alongside this technological change came a subtler, deeper transformation in Japan’s social structure. The close-knit, high-context neighborhood communities that the sentō once supported and nurtured began to unravel. As urbanization progressed and nuclear families became standard, life became more privatized. The old communal neighborhood spirit gave way to a stronger focus on individual privacy and personal space. For younger generations raised with their own bathrooms, the idea of hadaka no tsukiai—socializing while naked—felt less like a liberating social equalizer and more like an awkward, even embarrassing, situation. Why strike up a conversation with a semi-naked neighbor when you could be texting friends or scrolling through Instagram? The concept of casual, unstructured social interaction between diverse age groups started to fade. Moreover, the faster pace of modern life made the relaxed, hour-long sentō ritual seem inefficient in a world defined by overtime and long commutes. The dominant attitude became mendokusai—“it’s a hassle.” The ease of taking a quick shower at home simply outweighed the inconvenience of a trip to the public bath. The social advantages that once drove the sentō’s popularity no longer held enough value to offset the effort involved.

The Economic Squeeze

Even for sentō that still had loyal patrons, the economic challenges grew more severe. Operating a bathhouse is demanding and labor-intensive. Many owners, having inherited their businesses from parents, were aging, while their children, often university-educated and pursuing office jobs, showed little interest in assuming the physically grueling, low-margin family business that required late-night work. This created a major succession dilemma. Adding to this were rising maintenance costs. The bathhouses were old, with complex boilers and plumbing systems needing constant, costly repairs. Fuel prices increased, yet entrance fees remained regulated by local authorities to keep them affordable, squeezing profit margins dangerously thin. The final blow for many urban sentō was the soaring value of the land they occupied. A small, family-run bathhouse in a prime Tokyo location sat on extremely valuable property. For an aging owner without a successor and facing mounting repair expenses, the economic sense of selling the land to a developer for a lucrative apartment building or parking lot became unavoidable. The community hub that was once priceless now carried a price tag too high to ignore.

The Sentō Renaissance? A Modern Remix

Just when it seemed the sentō was destined to fade into history, something intriguing began to unfold. Over the past decade, a fresh wave of energy has started to ripple through the public bath scene. While this isn’t a full revival—the overall numbers are still on the decline—it represents a creative, focused renaissance. A new generation of owners, designers, and patrons are reimagining the sentō not as a nostalgic artifact, but as a platform for a fresh kind of social experience. They are taking the core aspects of the Showa-era bathhouse—the community, relaxation, and aesthetic—and adapting them for a 21st-century audience. The outcome is a captivating hybrid: part bathhouse, part social club, part art space, and all about the vibe.

From Bathhouse to “Brand”

The most obvious sign of this revival is the emergence of “designer sentō” or “renovation sentō.” Rather than allowing the old structures to fall apart, a new wave of entrepreneurs is investing money and creativity into updating them. These projects honor the classic architecture while adding a modern touch of cool. You might find a traditional bathhouse where an old boiler has been turned into a craft beer taproom or where the lobby doubles as a DJ booth or pop-up art gallery. Places like Koganeyu in Tokyo’s Sumida ward and Kosugi-yu in Koenji are standout examples. They’ve preserved the iconic Fuji mural and hot baths but added cutting-edge saunas (which have become hugely popular among the dedicated “saunner” subculture), sleek minimalist design details, and co-working spaces. They’ve transformed the sentō from a simple utility into a destination, a brand. These venues host events, sell stylish merchandise, and excel at social media. They’re not just offering a bath; they’re selling an experience, a lifestyle. This approach attracts a younger, more diverse crowd who might not have been interested in their local, traditional sentō but are drawn to these curated, multi-functional cultural hubs.

Nostalgia as a Vibe

Ironically, one of the strongest factors in the sentō’s renewed appeal is its age. For a generation raised amidst the sleek yet often sterile Heisei and Reiwa eras, the Showa period carries a powerful aesthetic charm. The term Showa-retro has become shorthand for a warm, analog, slightly kitschy style that feels more authentic and human-scaled than today’s minimalist trends. The very elements that once made sentō seem outdated—colorful tiles, wooden lockers, glass milk bottles—are now among their main attractions. Visiting a sentō has turned into an aesthetic pilgrimage, offering a chance to step into a living piece of history and snap the perfect nostalgic photo for Instagram. This allure is especially strong among international tourists who regard sentō as one of the most genuine and accessible ways to experience traditional Japanese culture. They seek a vibe, a mood, a real trip back in time that a museum often cannot provide. This has created new economic incentives for owners to preserve, rather than demolish, the classic features of their bathhouses.

A New Kind of Community

So, is the legendary community spirit of the Showa sentō making a return? The answer is both yes and no. The old model of community rooted purely in geographic proximity—where the entire neighborhood would gather out of necessity—is likely gone for good. However, the revitalized sentō are fostering a new kind of community based on shared interests and affinities. The sauna boom, for example, has created a passionate community of enthusiasts who travel between sentō to experience unique saunas and cold plunges, bonding over this shared interest. Others are drawn by music events, art, or the overall retro-cool atmosphere. This is a chosen community, not one of obligation. People attend these new sentō not simply to be with neighbors, but to be with “their people,” those who share their specific passions. It’s less like the neighborhood living room and more like a modern “third place”—a physical hub for a subculture that might otherwise exist only online. It’s a different social dynamic, but it demonstrates that the fundamental human need for a physical space to gather and connect hasn’t vanished; it has simply evolved into a new form.

So, What’s the Real Deal with Sentō Today?

So, after all this, where does the sentō stand? Is it a fading relic or a culture on the rise? The honest answer is that it is both. The classic Showa-era sentō, in its original role as the indispensable, essential center of daily neighborhood life, is undeniably a declining institution. Its downturn was a natural, inevitable result of Japan’s economic growth and social transformation. The emergence of the private home bath fundamentally changed the dynamic, shifting the sentō from a necessity to a choice. And in the contest between public ritual and private convenience, convenience nearly always prevails. The thousands of sentō that have shuttered over the past fifty years stand as silent testaments to this profound societal shift—a move from a communal, neighborhood-focused way of living to a more private, family-oriented existence.

However, to declare the sentō dead would be to completely miss the point. The experience has simply evolved. For those that survive and innovate, the sentō has found a new role. It’s no longer about basic utility; it’s about a curated experience. It’s a destination for relaxation, a sanctuary for the growing community of sauna enthusiasts, a tangible link to the past for nostalgia seekers, and a photogenic setting for tourists and Instagrammers. The new, revitalized sentō emphasize less the old-school hadaka no tsukiai of the entire neighborhood and more the creation of a “third place” for self-selecting communities of interest. The connection remains, but it is more specialized, more deliberate. You don’t visit the sentō to see the familiar faces you encounter daily; you go to be with people who, like you, have consciously chosen to be there for a particular reason, whether it’s the quality of the water, the heat of the sauna, or the appeal of the brand.

For anyone visiting or seeking to understand Japan, stepping into a sentō today is an act of cultural time travel. Whether you enter a beautifully preserved, Showa-era bathhouse run by a third-generation owner or a sleek, modernized designer sentō serving craft beer, you are engaging with a living piece of social history. You feel the echoes of a time when “community” wasn’t just a buzzword but a simple, steamy, daily reality. Grasping the sentō’s journey—from necessity to nostalgia—is to understand a central paradox of modern Japan: a deep yearning for the warmth and connection of the past coexisting alongside an unyielding push toward greater privacy and individualization. The trade-off was clear: the convenience of a private bath in every home in exchange for the casual, multi-generational, naked communion of the neighborhood’s living room. Whether that was a fair trade remains one of the great unresolved questions of Japan’s modern narrative.