Yo, what’s up? Megumi here. So, picture this: you’ve hopped off a local train in some Japanese town you’ve never heard of. You’ve seen the epic temples and the glowing neon signs on social media, so you’re expecting one or the other. But what you find instead is… this thing. A colossal, geometric fortress of gray, weathered concrete. It looks like a sci-fi spaceship from a ’70s movie decided to retire in a quiet neighborhood. It’s huge, it’s imposing, and it’s kinda… ugly? It’s not a government office, not an apartment block. You check the sign, and it says something like 「市民会館」— Shimin Kaikan, the Civic Hall. And then you start noticing them everywhere. In cities, in suburbs, in the middle of nowhere. These concrete behemoths are all over Japan, silent and stoic. You’ve gotta wonder, what’s the deal? Why did a country famous for its delicate wooden temples and minimalist design get so obsessed with building these massive, brutal concrete boxes?

It’s a legit question. These buildings totally mess with the international image of Japan. They don’t fit the serene wabi-sabi aesthetic or the high-tech cyberpunk vibe. They’re something else entirely, a ghost from a different era. But here’s the tea: these buildings are not just architectural oddities. They are time capsules. They hold the soul of a specific, incredibly intense period in Japanese history—the Showa Era (1926-1989), especially the high-growth decades after the war. They are the physical embodiment of a nation’s collective dream, its anxieties, and its soaring ambitions. To understand these concrete giants is to understand the heart of modern Japan. They’re not just ‘ugly’ buildings; they are, in their own powerful way, some of the most honest and important structures in the entire country. And their story is way more epic than you’d think. Before we dive deep into the concrete jungle, get your bearings and check out a prime example of this architectural energy.

To fully grasp this architectural energy, you need to understand the philosophy of Japan’s organic Brutalism.

The Vibe Shift: From Ashes to Concrete Ambition

To understand why these buildings exist, you need to rewind the clock. Mid-20th century Japan was worlds apart from the country we see today. It was a nation literally starting from scratch. The Second World War had devastated major cities, leaving behind vast landscapes of ash and rubble. The national spirit was broken. The immediate post-war years focused on survival, but with the arrival of the 1950s, a new drive began to emerge—an energy fueled by raw ambition. The mission was clear: rebuild, modernize, and catch up with the West. And the material chosen for this monumental effort? Concrete.

Rebuilding the Dream, One Concrete Block at a Time

Why concrete? It was practical, of course. Relatively inexpensive, durable, and most importantly, fireproof—a crucial psychological comfort for a nation whose wooden cities had been destroyed by firebombing. But concrete was more than just a building material. It was symbolic. It represented the future. Modern, strong, and permanent. While wood symbolized the past, tradition, and fragility, concrete embodied the new Japan. It was a bold statement that the nation was not merely restoring what was lost but creating something entirely new and unbreakable.

This era was driven by a powerful sense of collective purpose. The government, corporations, and citizens were all united in their efforts. The 1964 Tokyo Olympics became the ultimate national project, a deadline for Japan to prove to the world that it had returned. This event sparked a massive construction boom—new highways, the iconic Shinkansen bullet train, and modern buildings sprang up rapidly. At the heart of this transformation was the Civic Hall. These buildings were more than structures; they were symbols. Each one was a trophy, tangible proof of Japan’s success. It was progress you could touch, a fortress of hope built for the community.

The High-Growth Hangout

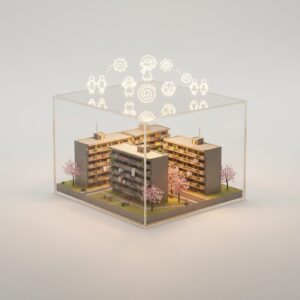

As Japan entered its economic miracle period from the late 1950s to the 1970s, civic hall construction surged. Japan was no longer just recovering; it was growing wealthy at a dizzying rate. National pride soared, and this pride found expression in public architecture. Every prefecture, city, and sizable town wanted its own cultural center, a bunka kaikan or shimin kaikan. Owning a grand, architect-designed civic hall became the ultimate status symbol for a local municipality. A prestigious public investment, it rewarded civic pride.

These halls were designed as the community’s living rooms—intensely democratic spaces. They housed libraries, concert halls, meeting rooms, exhibition spaces, and sometimes even wedding halls. This was where children had their first piano recital, where local seniors practiced their chorus, where you attended lectures, theater productions, or town meetings. They served as the cultural and social heart of the community, a physical anchor in a rapidly changing society. In an era before everyone had internet or endless home entertainment, these public halls were where community was built. Their imposing, sometimes daunting exteriors concealed a warm, human purpose.

Speaking Concrete: The Language of Brutalism, Japan Edition

Alright, so we understand the historical background. Yet, that alone doesn’t fully clarify why these buildings have such a raw, aggressive concrete appearance. This style belongs to a worldwide architectural movement called Brutalism, which thrived from the 1950s to the 1970s. The term originates from the French béton brut, meaning ‘raw concrete.’ The entire philosophy emphasized honesty—no concealing the structure behind plaster or paint. The building should reveal exactly what it’s made of and how it’s supported. It was a bold, no-frills approach. Japanese architects didn’t merely imitate this trend; they perfected it and infused it with a distinctive Japanese essence.

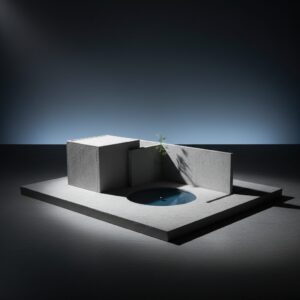

It’s Not Ugly, It’s Uchi-ppanashi

The Japanese word for the exposed concrete aesthetic is uchi-ppanashi, which literally means ‘poured-in-place and left as is.’ While that sounds straightforward, achieving the smooth, almost silky finish seen in the finest examples demands an extraordinary level of skill. It requires remarkable precision from the carpenters who construct the wooden molds, or katawaku, into which the concrete is poured. Every seam and joint in the woodwork will be stamped onto the final surface. The forms must be watertight and flawlessly smooth. This craftsmanship feels almost paradoxical given the raw, rugged nature of the material itself. It’s this concealed meticulousness that raises Japanese Brutalism to another level.

Architects such as Kunio Maekawa (a disciple of the legendary Le Corbusier in Paris) and Kenzo Tange emerged as the stars of this period. They regarded concrete not as a cheap, industrial material, but as something with noble, expressive potential. They explored its textures, its density, and how light and shadow played across its surfaces. While Western Brutalism sometimes felt gritty and dystopian, the Japanese variant often conveys a unique sense of refinement and calm. Some critics even relate the uchi-ppanashi aesthetic to traditional Japanese ideas, like valuing natural materials and the austere simplicity found in Zen gardens. It might be a stretch, but there’s a shared respect for a kind of raw, unembellished beauty.

Monumental Forms for the Masses

These civic halls were intended to make a powerful statement. Their architectural language is all about scale, drama, and strength. You see huge geometric shapes, daring cantilevers that appear to defy gravity, and heavy-looking structures lifted on pilotis (pillars), creating open public spaces beneath. These were not modest buildings; they were designed to inspire awe. They acted as secular cathedrals for a modern, democratic society.

Stepping inside feels like entering another realm. The acoustics shift. Your footsteps echo through the expansive lobbies. Grand, sculptural staircases carry you upwards. The air feels cool and still. The sheer mass of concrete surrounding you evokes a sense of permanence and solidity. These spaces were crafted to make ordinary citizens feel significant. Attending a concert or graduation in one of these halls became a special occasion. The architecture itself elevated the events within. It sent a powerful message: culture, community, and civic life matter—and they deserve a monumental home.

A Tour Through Time: Reading the Soul of Showa Concrete

To truly capture the vibe, you need to look beyond the theory and experience the buildings firsthand. The famous, architecturally notable ones are impressive, but it’s in the thousands of smaller, local halls that the spirit of the Showa era really comes alive. Each structure tells a story about the time it was created.

The Diplomat: Kyoto International Conference Center (1966)

This building is an absolute icon. Designed by Sachio Otani, it stands as a masterpiece of metabolic and Brutalist architecture. Nestled in a picturesque northern Kyoto setting, it refuses to blend in and instead boldly announces itself. Its design features a series of dramatic inverted trapezoids that form a stunningly intricate and futuristic silhouette, almost as if it might lift off at any moment. This building wasn’t just built for locals; it aimed to be Japan’s global diplomatic stage. It was a bold statement signaling Japan’s return as a major world player. Walking through its vast, sloping corridors and complex atriums feels like stepping onto the set of a vintage sci-fi film. It’s best known as the site where the Kyoto Protocol on climate change was signed in 1997. The building’s ambitious, forward-thinking design perfectly complemented a treaty focused on shaping the planet’s future. It’s Brutalism serving as a symbol of global vision, a concrete vessel for international diplomacy, embodying the height of Japan’s post-war confidence.

The People’s Palace: Kurashiki City Hall (1960)

While the Kyoto center represents global ambition, Kenzo Tange’s Kurashiki City Hall embodies democratic ideals. Situated in the historic city of Kurashiki, renowned for its traditional canals, Tange avoided creating a sealed fortress. Instead, he forged a building deeply connected to the public. He drew heavily on traditional Japanese wooden temple architecture, especially the interlocking beam systems seen in places like Todai-ji Temple in Nara. This influence is evident in the exposed concrete beams and columns that form a striking, rhythmic grid. Elevated on pilotis, the structure creates a spacious public plaza underneath that seamlessly flows into the main lobby. This was a revolutionary concept at the time: a government building genuinely open to the people. It’s a space that welcomes visitors. Tange designed it not merely as an office but as a genuine civic center, a gathering place for the community. It reflects the optimistic, democratic spirit of the early post-war period—an ideal rendered beautifully in concrete craftsmanship. Standing in its open plaza, one can feel the building’s civic-minded heart.

The Local Legend: The Everyday Kouminkan

Though the prominent examples are striking, the true essence of this story lies in the thousands of smaller, often anonymous civic halls—the kouminkan or chiku senta (community centers)—spread across the country. These are the unsung heroes of Showa-era public architecture. They might not have been designed by star architects, but they were built with the same spirit of civic pride and optimism. Discovering one is like uncovering a local treasure.

Stepping into one offers a full sensory experience. There’s a particular quietness, an institutional hush interrupted only by the squeak of shoes on linoleum floors. A distinctive scent lingers—a blend of old paper from library books, floor wax, and the faint aroma of green tea from a meeting room. The lobby is usually a vast, echoing space with worn but impeccably clean vinyl sofas and a dusty display case showcasing local crafts. The centerpiece is always the public bulletin board, a charming analog mosaic of community life: posters for upcoming summer festivals, handwritten notices for calligraphy classes, flyers for local politicians, and photos from senior citizens’ gateball tournaments.

These buildings are where life unfolded. They are steeped in the memories of millions of ordinary people. The main hall, with its heavy velvet curtains and rows of seats, has witnessed countless moments of personal and communal significance. It’s where a nervous five-year-old played their first piano recital, their small performance swallowed by the grand space. It’s where a high school band experienced its first disastrous gig. It’s where a couple, now celebrating their 50th anniversary, held their reception. It’s where a community gathered to watch the Olympics on a large screen, sharing a collective moment of national joy. These concrete walls have absorbed decades of applause, laughter, nervous silence, and the earnest, sometimes awkward pursuit of culture and connection. This is the true ‘soul’ of the concrete. It’s not found in architectural blueprints but in the accumulated human experiences these buildings have cradled. They are the quiet, humble theaters where the everyday drama of Showa life played out.

The Concrete Sunset: Preservation or Wrecking Ball?

For decades, these buildings blended into the background, largely taken for granted. But time inevitably catches up. The Showa era is now a part of history, and its concrete creations are experiencing a mid-life crisis. Many of these halls are over 50 years old and are beginning to reveal their age. The concrete is stained, the infrastructure outdated, and they often fail to meet modern earthquake resistance standards. For many local governments, they represent costly and inefficient relics of a past era.

The Cracks Begin to Appear

The practical challenges are significant. Concrete, though durable, is not everlasting. It cracks, becomes stained by rain, and suffers from weathering. Numerous buildings face issues such as asbestos or outdated electrical systems. They are notoriously energy-inefficient—harshly cold in winter and stuffy during summer. Renovation costs, especially for seismic retrofitting, can be exorbitant, often exceeding the expenses of demolition and new construction. Additionally, public tastes have evolved. The bold, heavy aesthetics of Brutalism fell out of favor. For a long period, these buildings were seen as dark, gloomy, and oppressive—the opposite of the light, airy designs favored today. Consequently, across Japan, the wrecking ball has been active. One by one, these irreplaceable architectural landmarks are being reduced to rubble.

The Retro-Futurist Renaissance

Yet, just as they vanish, a new generation is beginning to view them in a different light. A growing movement seeks to appreciate and preserve these Brutalist gems. Architecture enthusiasts, photographers, and young fans of the “Showa Retro” style are rediscovering their unique charm. On Instagram, countless images celebrate their powerful geometry, dramatic interplay of light and shadow, and nostalgic ambiance. They photograph beautifully—their monumental scale and textured surfaces provide a stunning backdrop.

This new wave of appreciation underscores the central dilemma: how to balance cultural heritage preservation with today’s practical needs and financial limitations. Some buildings are fortunate. They receive heritage status or are carefully renovated and repurposed, often as art museums or cafes. But for many smaller, local halls, the future remains uncertain. The debate over their preservation extends beyond architecture—it’s a conversation about which aspects of the Showa legacy deserve to endure. What value do we assign to these monuments of collective ambition in an increasingly individualistic society?

So, What Do These Concrete Giants Really Tell Us?

When you stand before one of these Showa-era civic halls, you’re seeing more than simply a structure made of concrete. You’re looking at a monument to a distinctive and unrepeatable chapter in Japanese history. This was a period of intense, collective national purpose. The nation was united by a single, overarching aim: to rebuild and foster a prosperous, peaceful future. These halls serve as the tangible embodiment of that shared determination. They were constructed with the conviction that public investment in community and culture was vital. They symbolized a society that, for a time, truly believed it was shaping a better tomorrow, together.

The current neglect or deterioration of these buildings tells a story about today’s Japan—a nation that is wealthier and more comfortable, yet increasingly fragmented and perhaps uncertain about its collective future. The communal aspirations of the Showa era have yielded to more diverse, individual ambitions. The gradual disappearance of these public halls reflects that transformation. The debate around their preservation is, in essence, a discussion about Japan’s own identity. What does community mean today? Which public spaces do we hold dear now?

So, the next time you find yourself in Japan and come across one of these concrete giants, don’t simply dismiss it as unattractive. Pause for a moment. Observe the texture of the walls, the striking lines, the way the light falls upon it. Try to envision the decades of human life that have unfolded within its strong embrace. These buildings are not silent; they whisper stories of a past dream. They are the quiet, concrete heart of modern Japan, and if you stand still and listen carefully within their echoing halls, you might just catch their pulse.