You’ve seen it, for sure. Scrolling through your feed, and bam—another pic of a super aesthetic Japanese house. It’s all clean lines, crazy geometric shapes, and massive windows. The vibe is immaculate. But then you zoom in. That wall… is that just… concrete? Like, the stuff from a parking garage? It’s gray, maybe a little uneven, with some weird little circle marks on it. It’s not painted. It’s not covered in fancy wallpaper. It’s just… raw. And you’re thinking, “Is this unfinished? Is this a design choice? Is this what they call peak minimalism, or did they just run out of cash?” It’s a total head-scratcher. In a world where luxury usually means polished marble, flawless finishes, and everything looking brand-spankin’-new, Japan’s architectural scene seems to be obsessed with a material that most people try to cover up. It feels like a glitch in the aesthetic matrix. You’re not wrong to be confused; it’s a look that goes against pretty much every Western design principle of overt opulence and manufactured perfection. But this isn’t about being lazy or cheap. In fact, it’s the exact opposite. This celebration of raw, imperfect concrete is a full-blown philosophical statement, a masterclass in an aesthetic concept that is fundamental to the Japanese soul: wabi-sabi. It’s not some mystical, ancient secret you need a password for. It’s a vibe, a way of seeing the world that finds insane beauty in things that are humble, flawed, and fleeting. And that “ugly” concrete wall? It’s the absolute star of the show. It’s time to decode why this seemingly boring material is considered the height of sophistication and how it unlocks a deeper understanding of Japan’s unique take on beauty.

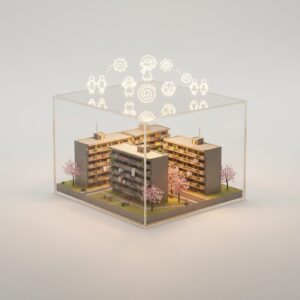

This appreciation for raw concrete extends beyond modern homes and is also a defining feature of Japan’s unique public housing projects, known as aging danchi.

The Lowdown on Wabi-Sabi: It’s Not What You Think

Before we even approach the concrete, we first need to grasp the concept of wabi-sabi. This term is often used loosely and inaccurately to describe anything rustic or aged in appearance. However, it encompasses much more than that. Wabi-sabi is not just an aesthetic; it is a worldview, a way of seeing and appreciating reality. It represents a profound shift away from the relentless chase for perfection that pervades modern life. It is a composite idea, blending two related yet distinct concepts that together form a powerful framework for understanding beauty. To truly comprehend wabi-sabi, it’s necessary to explore both parts of the idea, as each contributes something vital, and their union is what gives the concept its deep significance.

Abandoning the ‘Perfect’ Ideal

Let’s begin with wabi (侘). At its heart, wabi is about finding beauty in simplicity and valuing the quiet contentment that comes from a life free of excess. Consider it the original, spiritual form of minimalism, existing long before it became a buzzword. Wabi celebrates the understated elegance and the richness found in emptiness. It’s the sensation evoked by a simple, unembellished wooden bowl that fits comfortably in your hands, shaped by its function and the natural grain of the wood. It honors objects or spaces that do not demand attention but instead invite thoughtful contemplation. Historically, wabi gained prominence with the rise of the Japanese tea ceremony, especially under the guidance of the renowned tea master Sen no Rikyū in the 16th century. He rejected the extravagant, ornate Chinese-influenced tea ceremonies favored by the elite, which relied on luxurious, flawless utensils. Instead, he promoted a style that was rustic, simple, and profoundly humble, using locally produced pottery and bamboo tools that were sometimes slightly irregular. This was not about poverty but a deliberate choice to seek spiritual richness through material simplicity. Wabi recognizes that true fulfillment arises not from accumulation but from appreciating the essential and authentic.

Now, moving to sabi (寂). While wabi emphasizes humble simplicity, sabi is about the beauty created by the passage of time. Sabi appreciates the signs of age—the marks of a life lived—which appear as patina developed through years of use and exposure. It is the subtle scent of aged wood in a temple, the gentle moss covering a stone lantern in a garden, or the intricate web of cracks in the glaze of an old ceramic cup, such as those repaired with gold in kintsugi. Sabi finds profound beauty in natural cycles of growth, decay, and eventual death. It accepts impermanence as a source of aesthetic and spiritual depth instead of resisting it. Sabi reads stories in every rust stain, faded fabric, and weathered wood. It is a beauty earned, not manufactured, opposing the anti-aging, ever-new culture. It teaches that the scars and wrinkles of time are not defects to conceal but the very essence of an object’s character and charm—a visible record of its journey and resilience.

So, Wabi-Sabi is… A Mindset Shift

Combining these two concepts gives us wabi-sabi: a worldview that honors beauty that is “imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete.” It fundamentally diverges from classical Western notions of beauty, rooted in Greek and Roman ideals that prize symmetry, magnificence, permanence, and flawlessness. Picture the Parthenon in its idealized, perfectly proportioned original form, or a Renaissance sculpture carved from flawless marble, striving for eternal, divine perfection. Wabi-sabi is the opposite. It does not aim to create grand, unchanging works that defy time. Instead, it works with time, allowing nature and circumstance to serve as co-creators of the aesthetic. A wabi-sabi object or space is beautiful because of its imperfections, not despite them. To relate, imagine the contrast between a brand-new, stiff pair of designer jeans and your favorite worn-in pair that has softened and faded over the years, molding to your body. Or a shiny new leather jacket versus a vintage one, cracked and scuffed, each mark telling a story of where you’ve been. Wabi-sabi captures that feeling of comfort from a well-loved object. It is the recognition that real beauty often lies in the authentic, the humble, and the marks of genuine existence. It invites us to slow down, observe carefully, and find profound beauty in the quiet, overlooked details around us. This perspective is the key to understanding the deep connection between Japanese architecture and raw concrete.

Enter Concrete: The Unlikely Hero of Japanese Minimalism

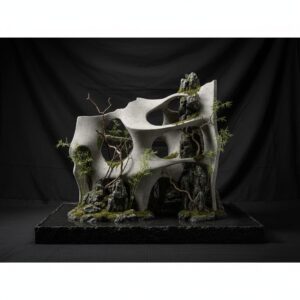

How does a modern, industrial material like concrete align with a philosophy rooted in natural processes and ancient tea ceremonies? At first glance, it seems like a stark contradiction. Concrete is man-made, harsh, and often linked to cold, impersonal urban environments. Yet, for a generation of Japanese minimalist architects, it became the ideal medium to express the wabi-sabi worldview in a contemporary setting. When stripped down and revealed, concrete embodies imperfection and impermanence in a way that is both striking and poetic. This was not simply about constructing with concrete; it was about elevating it from a mere structural element to an aesthetic focal point, a canvas for the intangible forces of nature.

Tadao Ando: The Master of Concrete Elegance

When discussing Japanese minimalist architecture and concrete, one name stands out as synonymous with the movement: Tadao Ando. He is the undisputed master who transformed exposed concrete into a sophisticated art form. A self-taught former boxer from Osaka, Ando’s architectural approach is visceral and elemental. He doesn’t merely design buildings; he orchestrates experiences. For him, concrete isn’t just a cheap or convenient material to cover up—it is the centerpiece. His philosophy centers on creating serene, contemplative sanctuaries that connect people with nature, even amid dense urban settings. His chosen medium is meticulously crafted, beautifully raw concrete. He treats concrete not as a blunt tool but as a delicate fabric, capable of capturing subtle nuances of light and shadow. His signature work features vast, smooth, silk-like surfaces of exposed concrete, punctuated by dramatic voids, sharp geometric cuts, and carefully positioned openings that allow natural light to flood in, transforming the interior throughout the day. Buildings like the iconic Church of the Light in Ibaraki or the Chichu Art Museum on Naoshima Island are not just structures; they are immersive environments designed to evoke emotional and spiritual responses. He demonstrated that this seemingly cold, industrial material could be used to create spaces full of warmth, tranquility, and profound beauty.

Why Concrete Embodies Wabi-Sabi Perfectly

Ando’s brilliance, alongside the minimalist architects who followed his lead, lay in recognizing concrete as an inherently wabi-sabi material. They didn’t impose the philosophy on it; rather, they revealed what was already present. Here’s how the material aligns perfectly with the core principles of this aesthetic:

It Embraces Natural Imperfection

To achieve his signature smooth finish, Ando’s concrete is poured into custom-designed, high-precision wooden formwork, often made from lacquered plywood. When removed, the formwork leaves a subtle imprint of its wood grain, adding texture and vitality. More importantly, the surface is never flawlessly uniform. Slight variations in color and tone emerge from the complex chemical processes during curing. Tiny air bubbles called pinholes become trapped against the formwork, creating a constellation of small voids. Then there are the tie-holes—circular indentations left by steel rods holding the formwork in place during pouring. In typical construction, these so-called “flaws”—the texture, color shifts, pinholes, tie-holes—would be deemed defects to be patched, sanded, and hidden with plaster and paint. But in the wabi-sabi perspective, these are not flaws. They are celebrated as honest expressions of the material’s nature and the process of its making. They are the concrete’s unique fingerprint, a record of its liquid origins. These imperfections lend depth and character far beyond what a perfectly flat, painted wall could provide. They represent the wabi of the material—its humble, unembellished truth.

It Reflects Beautiful Impermanence

This is where sabi manifests. Concrete is not static; it is porous and lives, breathes, and transforms over time. Exposed to the elements, it becomes a living record of its environment. Rainwater leaves subtle, ghostly streaks called efflorescence, forming a unique patina that evolves over years and decades. Sunlight causes microscopic expansions and contractions, which can result in fine, hairline cracks. In humid climates, moss or lichen may sprout in shaded recesses. The concrete’s color can slowly change, fading or darkening depending on exposure to sun and moisture. For an architect adopting the wabi-sabi ethos, these changes are not decay or deterioration. They are the building maturing, gaining character, accumulating stories. The structure is designed not to remain pristine indefinitely but to age gracefully, wearing the passage of time as a badge of honor. This slow, inevitable transformation is the physical embodiment of sabi—a poignant and beautiful reminder of the impermanence of all things. The building is not merely located somewhere; it is of that place, continuously interacting with and shaped by the natural world around it.

More Than Just a Look: It’s a Feeling

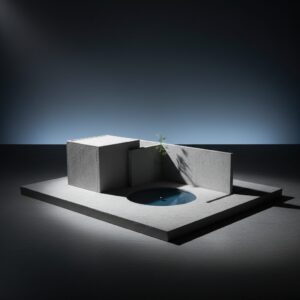

Grasping the philosophy is one aspect, but the true strength of this architectural style lies in how it makes you feel. Choosing to use raw concrete is not merely an intellectual application of wabi-sabi principles; it is a deliberate approach to crafting a particular human experience. These spaces are designed to engage the senses and calm the mind, offering a haven from the sensory overwhelm of contemporary urban life. The emphasis moves from what you observe to what you undergo—the quality of the silence, the texture of the air, the slow movement of light across a textured surface. This architecture values the internal over the external, the emotional over the material.

The Space Inside: A Sanctuary from the Chaos

Entering a structure like Tadao Ando’s Church of the Light, you immediately feel this. The space is strikingly simple: a box of flawless, smooth concrete. There are no paintings, no traditional stained glass, no ornate embellishments. The sole decoration is a cross-shaped aperture cut into the wall behind the altar, through which raw, unfiltered daylight streams into the dim interior. The impact is profoundly moving. The thick concrete walls serve a crucial purpose beyond merely supporting the roof: they foster a deep sense of enclosure and calm. They absorb sound, muting exterior noise and creating an almost sacred silence inside. The air feels still and cool. In this profound quiet, your senses sharpen. You detect the faint, earthy scent of the concrete itself. You become vividly aware of the quality of light. That brilliant cross of light is not static; it travels across the floor and walls as the sun moves through the sky, a silent, slow-motion sundial marking time. The raw, textured surface of the concrete catches this light in a way a flat, white wall never could. The tiny imperfections, pinholes, and form lines give the light something to cling to, producing a soft, diffused glow and deep, changing shadows. The space compels you to slow down, to be present, to simply observe. It is a meditative experience, a form of sensory reduction that enables a deeper spiritual or emotional connection. It transcends religion; it creates a space for introspection. The minimalism is not emptiness; it is rich with potential for personal reflection.

Connecting to Nature (Even When There Isn’t Any)

It may seem paradoxical that a heavy, opaque, man-made material like concrete can connect people with nature, yet this is one of the defining paradoxes and victories of this architectural style. Japanese minimalist architects do not use concrete to shut out nature but to frame it, curate it, and amplify our experience of it. A massive, austere concrete wall may feature a single, perfectly placed, floor-to-ceiling window looking out onto no more than a solitary bamboo stalk or a small patch of mossy ground. The stark, monolithic concrete wall acts as a neutral, silent backdrop, focusing all your attention on that tiny, living element. It elevates the bamboo from a simple plant to a living sculpture. The contrast between the raw, gray, unchanging concrete and the delicate, green, ever-shifting plant life is strikingly dramatic. The building essentially becomes a frame, transforming the view into a living artwork. Additionally, the interplay of light and shadow across concrete surfaces directly links the building’s interior to the natural world outside—the time of day, weather, and season. A cloudy day casts a soft, even light, making the space feel peaceful and solemn, while a bright sunny day produces sharp, dramatic shadows that shift and change, animating the space. In this way, the building functions as a receptor, an instrument that reflects and visualizes subtle natural changes. The elemental, almost geological character of the concrete itself evokes a primal bond with nature, as if inside a cave or stone sanctuary, offering a sense of shelter and permanence that is both grounding and deeply soothing.

Is It Just an Excuse for Being Unfinished? The Skeptic’s Corner

Alright, let’s be honest. By now, you might be thinking, “Okay, I understand the deep philosophy, the wabi-sabi, the poetry of light and shadow… but seriously, isn’t it simply much cheaper and easier to leave the concrete walls bare than to hire people to plaster, sand, and paint them?” It’s a fair question, and your skepticism is completely reasonable. From a distance, it can appear to be an aesthetic born from budget constraints or a kind of high-concept laziness. However, the reality of achieving the flawless, beautiful exposed concrete seen in high-end Japanese architecture is quite the opposite. It’s an incredibly demanding, technically intricate, and exorbitantly expensive process. This isn’t your typical rough-and-ready construction concrete. It’s a luxury material, crafted with the precision of a master artisan.

The ‘But Why?’ Question

Here’s the explanation. Creating that perfectly smooth, seemingly simple surface demands an extraordinary level of craftsmanship and control at every stage of the process. The concrete mix itself is a proprietary formula, with the precise ratio of cement, sand, aggregate, and water tailored to produce a specific color, texture, and strength. The wooden forms into which the concrete is poured must be constructed with microscopic accuracy. Any slight warp, gap, or flaw in the wood will be permanently transferred onto the concrete surface. This is why architects like Ando use expensive, specially coated plywood to ensure near-perfect smoothness. Pouring the concrete is a high-pressure, one-shot event. It has to be done all at once to prevent visible lines or color variations between pours. The workers must vibrate the wet concrete perfectly to eliminate large air pockets without causing other imperfections. Even the placement of the tie-holes, those small circles, is carefully planned to create a deliberate, rhythmic pattern on the wall. They are elements of the design, not accidental byproducts. When you see a wall of this architectural concrete, you’re witnessing a testament to obsessive quality control. Ironically, it is much easier and cheaper to conceal mistakes. If the concrete pour is sloppy, you can just apply plaster, sand it, and paint over it. No one would ever notice. But with exposed concrete, there’s no place to hide. Every mistake, shortcut, and moment of carelessness is etched into the surface forever. So, far from being a lazy or inexpensive choice, exposing the concrete is a massive statement. It’s a quiet declaration of supreme confidence in the quality of your materials and the skill of your craftsmen. It’s the architectural equivalent of a no-makeup selfie; it demands deep, underlying perfection to pull off successfully.

Real vs. Insta: The Lived Experience

Now, for some honest talk. Does this aesthetic have its drawbacks? Absolutely. What looks breathtakingly serene in a carefully composed, professionally lit Instagram photo doesn’t always translate to a comfortable reality. These spaces can feel, and literally be, very cold. Concrete has poor thermal insulation, making these buildings chilly in winter and often cool and damp in summer. The austerity can also feel emotionally cold to some. It’s not a cozy, warm, “hygge” kind of comfort. It can come across as severe, impersonal, and even intimidating. Hard surfaces create harsh acoustics where every sound echoes. On a sunny day, the play of light can be magical. On a long, gloomy, rainy day, being surrounded by vast gray expanses can feel oppressive. This aesthetic demands a certain mindset from its inhabitants. It’s not for everyone. It asks you to find beauty in austerity and appreciate a more contemplative, perhaps less traditionally comfortable, way of living. It’s an important reminder that the idealization of this style online often overlooks the practical and emotional challenges of actually living in these spaces. The experience is subjective. You either deeply connect with the stark, meditative vibe, or you feel like you’re living in a very stylish bunker. And honestly, either response is completely valid.

So, Next Time You See a ‘Boring’ Gray Wall…

Hopefully, the next time you’re scrolling and come across an image of a Japanese minimalist masterpiece, that plain gray wall won’t seem so dull or incomplete anymore. You’ll recognize it for what it truly is: a deliberate and profoundly philosophical choice. It’s a canvas carefully prepared, not for paint, but for the subtle and profound interplay of light, shadow, and time. It’s a surface rich with the story of its own making, where every tiny pinhole and faint line is celebrated as a mark of authenticity. It’s a quiet rebellion against the loud, disposable, and endlessly new culture of today.

That vast expanse of raw concrete is a physical expression of wabi-sabi. It finds beauty in its own humble, imperfect nature (wabi) and is designed to gracefully accept and showcase the inevitable marks of age and experience (sabi). It invites us to discover richness in simplicity, to observe the drama in sunlight shifting across a room, and to embrace the fleeting, beautiful nature of existence. It’s architecture not just for shelter but for creating a space that soothes the spirit and sharpens the mind. It’s not about what’s there—the costly furniture, the fancy art, or ostentatious displays of wealth. It’s about what the apparent emptiness, the carefully curated ‘nothingness,’ makes you feel. And that, quietly, is the whole essence of Japanese minimalism. If you know, you know.