Yo, what’s good fam? Hiroshi Tanaka on the deck, coming at you straight from the heart of Japan. So you’ve scrolled the feeds, right? You’ve seen the neon rivers of Shibuya, the serene bamboo forests of Arashiyama, and maybe even a thousand pics of that floating torii gate. It’s all fire, no cap. But then you see it—flicking past a reel or in the background of some indie J-film. Rows and rows of identical, weathered concrete apartment blocks. They ain’t sleek. They ain’t ancient. They just… are. And you might think, “What’s the deal with those? They look kinda grim.” But hold up. You’re looking at a piece of Japan’s soul that most tourists fly right over. You’re looking at a danchi (団地). These sprawling housing complexes are more than just old buildings; they’re the fossilized dreams of a bygone era. They were Japan’s post-war “Concrete Utopias,” a vision of a bright, modern future for everyone. Now, they’re time capsules, radiating a powerful, melancholic nostalgia that even foreigners can feel deep in their bones. It’s a vibe, a whole aesthetic that tells a story about modern Japan that a temple or a skyscraper never could. It’s about the rise, the fall, and the weird, beautiful comeback of the Japanese dream. Before we dive deep into this rabbit hole, get your bearings and check out one of the most iconic danchi complexes, Takashimadaira Danchi in Tokyo, to see what we’re talking about.

To truly understand this unique architectural landscape, you might also be fascinated by the hidden world of Japan’s underground cities.

The Birth of a Dream: Why Danchi Even Exist

To truly understand the danchi phenomenon, you need to rewind to 1950s Japan. The war had just ended, leaving the country in ruins. Cities like Tokyo and Osaka were devastated. On top of that, there was a massive baby boom and soldiers returning home. The consequence? A severe housing crisis. People lived in shacks, bombed-out buildings, or wherever they could find shelter. Traditional Japanese houses, made of wood and paper, were beautiful but utterly impractical for a nation needing millions of homes urgently. They were also fire hazards, a harsh lesson from the firebombings.

Then the government stepped in. In 1955, they founded the Japan Housing Corporation (JHC), now called the UR Urban Renaissance Agency. Their mission was monumental: rebuild Japan. The solution was not just housing but a whole new way of life. They drew inspiration from the West, embracing modernist architectural movements and urban planning ideas from figures like Le Corbusier. The aim was to create fireproof, earthquake-resistant, and, above all, modern communities for the growing salaried middle class. This is where the term danchi comes from, meaning “group land” (団体地). These were not just randomly placed apartment blocks; they were carefully planned mini-cities.

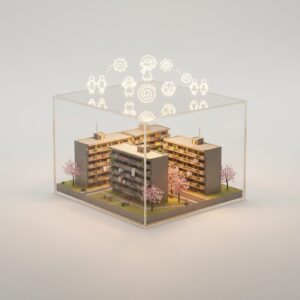

This was the utopian ideal. Each danchi complex was designed as a self-sufficient ecosystem. At its heart, there was almost always a shotengai, a lively shopping arcade featuring a butcher, fishmonger, vegetable stand, tofu shop, and a candy store for children. There would also be a post office, bank, clinic, and sometimes a barbershop. Green spaces and playgrounds were interspersed among the concrete buildings, meant as communal areas where families could gather and children could play safely, away from the emerging dangers of traffic. It was a vision of a clean, orderly, and convenient future, sharply contrasting the chaotic, cramped conditions most people had endured. Securing a place in a danchi was like hitting the jackpot. People lined up for days to enter highly competitive lotteries for the chance to live in these shining symbols of Japan’s recovery and its march toward prosperity. It was, in every way, the physical embodiment of hope.

“LDK”: The Blueprint for Modern Japanese Life

If the danchi represented the hardware of post-war Japan’s transformation, then the “LDK” floor plan was its operating system. This acronym, still found on nearly every real estate listing in Japan today, stands for Living, Dining, and Kitchen. While it may seem ridiculously simple to a Westerner, in post-war Japan it was a revolutionary concept that fundamentally reshaped Japanese family dynamics and home life.

To understand this, consider the traditional Japanese home beforehand: it featured multifunctional rooms with tatami mat floors. One room served as the living area during the day, transformed into the dining room at mealtimes (using low tables called chabudai), and became the bedroom at night when futons were rolled out from closets. The kitchen, or daidokoro, was typically a dark, smoky, and utilitarian space, regarded as the woman’s domain and separate from the family’s communal areas. Privacy among family members was fluid, with life centered around the floor rather than chairs.

The danchi apartment shattered that old model by introducing a Western-style spatial organization unfamiliar to most Japanese people. Suddenly, there was a dedicated room for each activity. The kitchen underwent the most dramatic change: often a sleek, stainless-steel space designed for efficiency, called the “Dining Kitchen” (DK), where cooking and dining took place together—usually with a dining table and chairs. This transition from sitting on the floor to sitting on chairs during meals marked a major cultural shift, elevating the kitchen from a backroom workspace to the heart of the home.

This is where the “Three Sacred Treasures” (三種の神器, sanshu no jingi) come into play, a playful nod to the Imperial Regalia of Japan, now used to describe essential consumer goods of the era. The danchi kitchen was built to accommodate these treasures: a television, a washing machine, and a refrigerator. These appliances were not mere conveniences but symbols of wealth, modernity, and a new, easier lifestyle. The danchi layout, the LDK model, was intensely aspirational. Widely promoted in the media as the ideal environment for the perfect modern nuclear family—a salaried-man father, a stay-at-home mother, and two children—it set a powerful new social standard that has shaped Japanese domestic life ever since. Living in a danchi was more than just having a new apartment; it was joining a national movement toward modernity.

The Vibe Check: Aesthetics and Atmosphere of Danchi

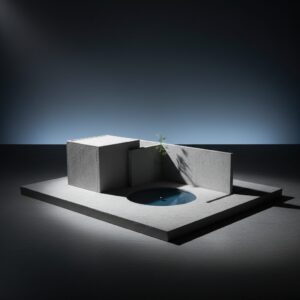

You can’t discuss danchi without mentioning the vibe. It’s an aesthetic, a mood, a feeling that’s difficult to define but immediately recognizable. Visually, it’s a lesson in repetition and order—endless rows of identical five-story concrete buildings often arranged in perfect geometric patterns across the landscape. The architecture directly descends from Brutalism, prioritizing function over form, though time has softened its harsh edges. The bare concrete bears stains from decades of rain, the once-bright pastel accents on railings and doors are now faded and peeling, and a patina of age gives each building a distinct character despite its cookie-cutter design.

There are iconic visual features. External concrete stairwells zigzag up the sides of each building. The metal railings of the balconies each bear slight differences from personal touches by residents—a forest of futons drying in the sun, a collection of potted plants, a forgotten child’s bicycle. The uniformity of the structures only emphasizes the individuality of the lives lived within. Then there’s the typography—the bold, sans-serif numbers stenciled onto the building exteriors, like 5-201, a starkly functional yet surprisingly stylish design choice that has itself become an aesthetic for a new generation.

The atmosphere goes beyond the visual; it’s also auditory. Danchi have a distinctive soundscape. In the afternoon, you hear distant kids playing in the central park, the rhythmic bounce of a ball against a concrete wall. The nostalgic tune of the tofu seller’s truck horn echoes as it makes its rounds, or the chime over the community loudspeakers at 5 PM signals children to head home. It’s a symphony of simple, communal life. The very arrangement of buildings surrounding a central common space amplifies these sounds, constantly reminding you that you are part of a collective.

At its core, the danchi was created to nurture a sense of community, or kizuna (bonds). The playgrounds, benches beneath trees, open-air corridors—all designed as stages for neighborly interaction. Yet the true heart of the community was the shotengai. It wasn’t merely a place to buy groceries; it was the neighborhood’s living room. The butcher who slipped you an extra slice of ham, the fishmonger who knew just how you liked your mackerel, the elderly lady at the candy shop who watched generations of children grow up. This dense web of human relationships formed the invisible architecture that held the danchi together, creating a world where everyone knew your name. This idealized sense of community is a major part of the nostalgic charm of danchi today.

The Dream Fades: From Utopia to “Old and Grim”

For a glorious couple of decades, the danchi reigned supreme as the symbol of Japanese housing. But nothing lasts forever. The very economic miracle that the danchi helped create would eventually contribute to its downfall. As Japan accelerated through the 1970s and 80s, the dream began to shift. The collective, uniform lifestyle of the danchi started to feel confining.

The biggest driving force was prosperity. The generation that once aspired to own a danchi apartment now had larger ambitions. The ultimate status symbol shifted from a modern apartment to a detached, single-family home with a small garden and a parking spot for the family car—this era marked the height of “my home-ism” (mai-hoomu-shugi). The danchi, once the pinnacle of aspiration, became merely a stepping stone, a place to live before acquiring a “real” house. The suburbs expanded, and people began moving out.

At the same time, the once-utopian housing started to show signs of aging. Concrete, once emblematic of permanence and modernity, began to appear dull and imposing. Apartments that felt spacious in the 1950s seemed cramped and outdated by the 1980s. The absence of elevators in the original five-story walk-ups became a major issue for aging residents. Meanwhile, newer, more luxurious private condominiums, known as “mansions,” emerged, offering better amenities, more space, and a more prestigious address. The danchi was no longer the fresh, trendy choice. It was becoming outdated.

This shift triggered a significant demographic change. The young families who had settled in the danchi in the 60s, full of hope and energy, remained. Their children grew up and, pursuing new dreams, moved away. What remained was a rapidly aging population. Danchi became synonymous with the elderly. This brought a new set of social challenges, most notably kodokushi, or “lonely deaths,” where elderly residents would pass away unnoticed in their apartments for days or even weeks. Once lively playgrounds fell silent. The bustling shotengai saw shops close one after another as owners retired and customers dwindled. The public image of danchi plummeted. What had once been a symbol of a bright future became a symbol of a forgotten past, aging infrastructure, and social isolation. The utopia was beginning to look very much like a dystopia.

The Comeback Kid? Nostalgia and New Appreciation

Just as it seemed the danchi were doomed to fade into obscurity, something unexpected happened. A new generation—one with no memory of the post-war housing crisis or the stigma of the 1980s—began to view these concrete giants through fresh eyes. Suddenly, the danchi started to become… cool.

This revival is driven by a major cultural trend: Showa Retoro (昭和レトロ), a profound nostalgia for the Showa era (1926-1989), especially its mid-century period of rapid economic growth. For young Japanese people, this time symbolizes optimism, simplicity, and strong community ties—a sharp contrast to today’s economic stagnation and social fragmentation. Danchi are the ultimate physical relics of this bygone golden age. They serve as living museums of Showa design, from terrazzo floors and frosted glass entryways to quaintly outdated kitchen fixtures. This retro aesthetic has become incredibly fashionable, celebrated in magazines, music videos, and on social media. People are actively seeking out the danchi vibe.

This cultural shift has been accelerated by some very savvy corporate collaborations. The best-known example is the partnership between UR (formerly JHC) and the minimalist lifestyle brand MUJI. Together, they renovate old, vacant danchi units and give them a total makeover. They strip out dated interiors, reveal the raw concrete framework, and install elegant wood flooring, modern kitchens, and MUJI’s signature minimalist fittings. They preserve the vintage spirit of the buildings while making the living spaces comfortable and stylish for contemporary lifestyles. This has turned danchi living into a genuinely appealing option for young creatives, remote workers, and families who prioritize design and community over a prestigious address.

Beyond aesthetics, there are compelling practical reasons behind the danchi’s resurgence. Japan’s major cities are prohibitively expensive. For young people starting out, a typical apartment often demands a large deposit, non-refundable “key money,” agent fees, and a guarantor—a significant barrier to entry. UR-managed danchi, however, often waive many of these upfront costs. The rent is usually lower for a larger space than you’d find in a privately owned modern building. This affordability makes danchi a smart, sensible choice. Young people are moving in, injecting new energy, starting families, and revitalizing communal areas with farmers’ markets, art projects, and community gardens. In some places, the original utopian ideal of a vibrant, multi-generational community is genuinely making a comeback.

So, Why Does It Feel Nostalgic, Even to a Foreigner?

We understand why Japanese people might feel nostalgic for danchi, but what about you? Why does a photo of a weathered concrete apartment block in a country you may never have visited still manage to tug at your heartstrings? The reason is that danchi tap into something far deeper and more universal than simply Japanese history.

One meaningful way to grasp this feeling is through the concept of “hauntology.” It isn’t nostalgia for a past you actually lived, but a longing for a lost future. Danchi perfectly embody this idea. They symbolize a very specific, collective vision of the future imagined in the mid-20th century—a future defined by social cohesion, modest prosperity, and orderly communal living. This was a dream shared by many nations after the war. To look at a danchi today is to see the ghost of that future—a future that never unfolded as anyone had anticipated. That subtle melancholy, the sensation of a promised tomorrow that has become a dated yesterday, resonates with anyone who feels the uncertainties of our current, more precarious world. It’s the visual equivalent of a faded photograph capturing a future that now feels more innocent and hopeful than our present.

Moreover, danchi often evoke the sensation of a “liminal space.” These are transitional, in-between places that feel both oddly familiar and slightly unsettling. Think of an empty school corridor on a weekend or a deserted airport late at night. The long, repetitive hallways of a danchi, the identical doorways, the silent playgrounds at dusk—they all possess this liminal quality. They are filled with echoes of lives once lived, a tangible sense of presence and absence. This atmosphere, which the Japanese might call mono no aware (物の哀れ)—a gentle sadness for the impermanence of things—is deeply moving and has made danchi a favorite subject for photographers and artists drawn to their quiet, contemplative beauty.

Finally, in an era when our image of Japan is often shaped by hyper-polished, consumer-driven portrayals of Tokyo’s trendiest neighborhoods or Kyoto’s iconic temples, danchi offer a dose of raw authenticity. They aren’t trying to sell you anything. They are unpretentious, functional, lived-in spaces that tell the story of millions of ordinary Japanese people across more than half a century. Exploring a danchi is like discovering a secret door that leads away from the curated tourist experience and into the quiet, everyday reality of the country. It provides an opportunity to see Japan not as a fantasy, but as a real place, with a complex history and a beautifully imperfect present. This sensation of a genuine, unfiltered glimpse behind the curtain is a powerful attraction for any inquisitive traveler.

Your Danchi Exploration Guide (Without Being a Tourist)

Feeling drawn to experience this side of Japan yourself? Great. But you need to do it properly. Keep in mind, these are not tourist spots; they are people’s homes. The objective is to be a respectful observer, not an intruder. Here’s how to soak in the danchi vibe without being awkward.

The best and most welcoming place to start is the shotengai, the shopping arcade. These are public commercial areas where your presence (and business) is generally appreciated. This is where you can truly feel the community’s heartbeat. Don’t just stroll through snapping photos. Engage. Buy a freshly fried korokke (croquette) from the butcher. Grab a unique snack from the local candy shop. Try to exchange a simple “Konnichiwa” with the shopkeepers. This is the most genuine way to experience the living culture of the danchi.

Next, explore the public spaces. The parks and green spots nestled between buildings are open for anyone to enjoy. Take a walk. Sit on a bench. Observe the complex’s layout. Notice the classic Showa-era playground equipment—the concrete animal sculptures, the globe-shaped jungle gyms, the oddly futuristic slides. These are relics of a different design mindset, built to last. Look for the central clock tower or the community bulletin boards, which often remain in use.

As you walk around, pay attention to the architectural details. Notice the textures of the concrete, the varying patterns of wear and tear. Observe the typography of building numbers and signs. See how residents have personalized their identical balconies with plants, laundry, and decorations, creating a beautiful tapestry of individuality amidst uniformity. These small details tell a rich story.

Most importantly, respect is key. Be discreet. Lower your voice. Avoid pointing your camera into windows or directly at residents, especially children. If you want to photograph someone, ask for permission first. Consider yourself a guest in a vast, open-air neighborhood. The goal isn’t to exoticize or document poverty; it’s to understand a vital chapter of Japan’s modern history and appreciate the quiet beauty of a lifestyle both fading away and being rediscovered. Approach it with respect, and you’ll uncover a side of Japan that is deeply authentic, powerfully nostalgic, and utterly unforgettable.