Yo, what’s the deal? You’ve been to Japan. You’ve seen the future—the neon-drenched streets of Shinjuku, the robot cafes, the toilets that are smarter than your phone. You’ve probably sipped a flawless, ethically-sourced, single-origin pour-over in some minimalist coffee temple that looks like an art gallery. It’s all sleek, it’s all clean, it’s all… expected. But then, you turn a corner, desperate for a quick caffeine hit, and you walk into a Doutor Coffee shop. And the vibe shifts. Hard. Suddenly, it’s not 2024 anymore. It’s 1996. The chairs are upholstered in a shade of burgundy velour you haven’t seen since your grandma’s house. The lighting is unapologetically fluorescent. The air hums with a quiet, functional energy, a world away from the performative chill of a third-wave cafe. You see a salaryman in a slightly rumpled suit, reading a newspaper—an actual, physical newspaper—and you think, “Where am I? And why does this place feel more real than anything I’ve seen on Instagram?”

This ain’t a glitch in the matrix, fam. This is the real Japan, the one that doesn’t always make it into the travel vlogs. This is the Japan that runs on quiet consistency, not flashy trends. Doutor isn’t just a coffee chain; it’s a living museum of the Heisei era, a cultural touchstone that tells you more about modern Japanese life than a thousand cherry blossom photos. It’s the ultimate “if you know, you know” spot for anyone trying to get past the surface. We’re not here to just list locations; we’re here to decode the vibe. To understand why these time capsules exist, why they’re cherished, and what they reveal about the soul of a country that’s constantly balancing its hyper-modern image with a deep-seated love for the comfort of the familiar. So grab a seat (just put your bag on it first, we’ll get to that), order a Blend Coffee, and let’s get into it. This is your deep dive into the world of Doutor, the unsung hero of Japan’s coffee scene.

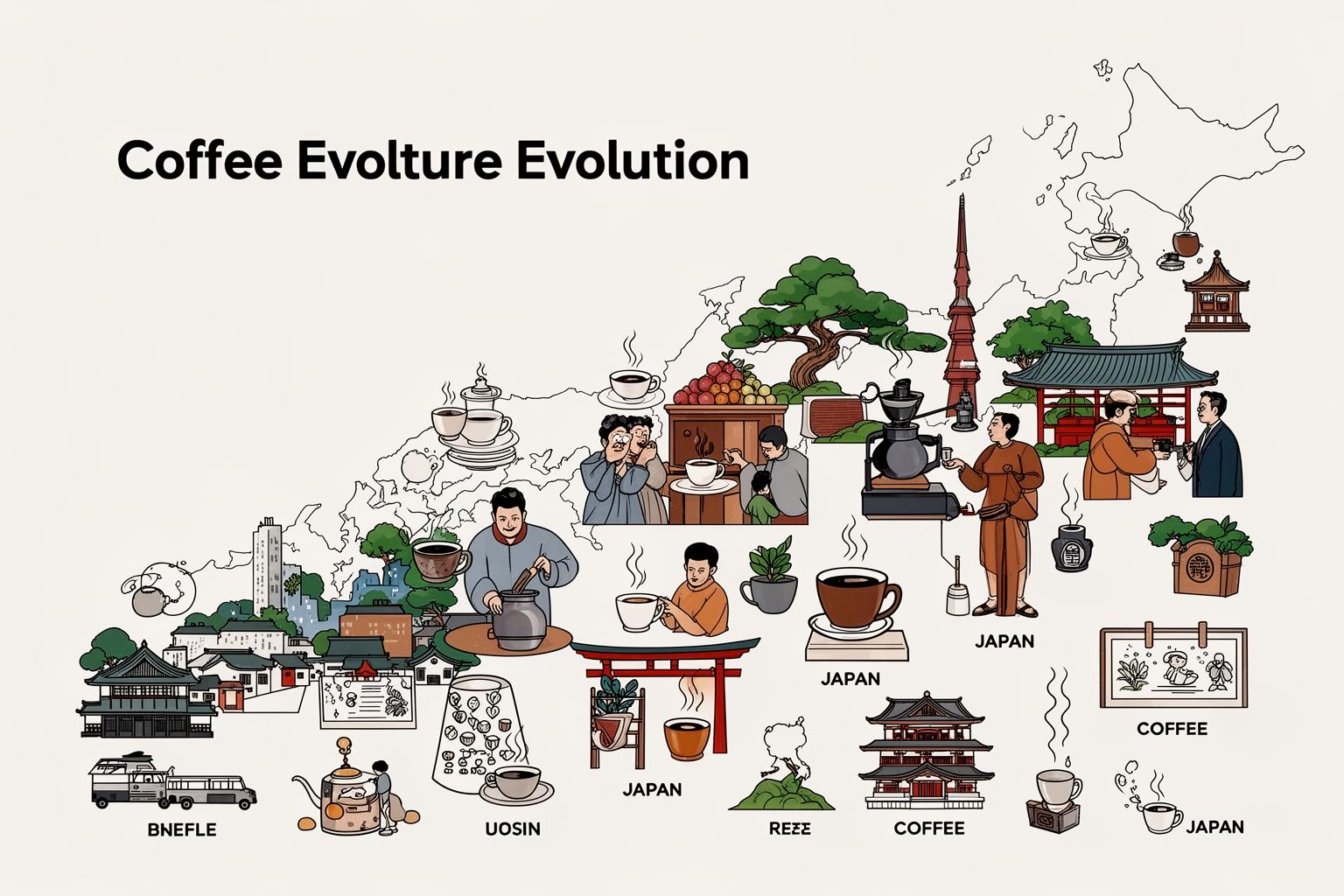

For a look at the other side of Japan’s coffee culture, explore the philosophy behind its minimalist cafes.

The Birth of the Kissaten and the Doutor Disruption

To understand why Doutor is what it is, you need to rewind and examine what came before. Prior to the rise of fast, affordable coffee chains, Japan had the kissaten. These were more than just coffee shops; they were institutions. Imagine dark, wood-paneled interiors, filled with the rich aroma of siphon-brewed coffee and, for many years, tobacco smoke. The seating was plush, often featuring high-backed booths that offered privacy. The soundtrack wasn’t a curated Spotify playlist; it was classical music or jazz, played at a respectful volume through a quality sound system. A kissaten was a destination—a place for serious business meetings, quiet reflection, reading a novel for hours, or deep conversation. Coffee was carefully prepared, often with theatrical siphon or flannel drip methods, and priced accordingly. It was a luxury—an affordable indulgence, but an indulgence nonetheless. The pace was slow, deliberate, and somewhat formal. The kissaten was Japan’s original “third place,” a sanctuary away from home and office.

Then, in 1980, Hiromichi Toriba arrived and turned the coffee scene upside down. Inspired by European stand-up coffee bars, he envisioned bringing a new type of coffee culture to Japan. His concept was simple yet revolutionary: to serve genuinely good coffee quickly and at a price accessible to everyone. This marked the birth of Doutor. The first shop in Harajuku was a game-changer. It wasn’t a dark, moody kissaten but bright, open, and efficient. The aim wasn’t to encourage lingering over one expensive cup for hours; it was to offer a high-quality pit stop in a busy day. This vision resonated deeply with 1980s Japan, amid the bubble economy’s rapid pace. Life was speeding up. People worked hard, commuted long distances, and had disposable income. Doutor fit perfectly into this new reality, providing a moment of accessible luxury—a quick, delicious caffeine boost without the time or financial commitment of a traditional kissaten. It democratized daily coffee, transforming it from a formal occasion to an everyday ritual for the masses. Doutor wasn’t about replacing the kissaten, but about creating a new category tailored to the needs of a modern, fast-paced society.

Decoding the “Retro” Aesthetic: It’s Not a Theme, It’s a Time Capsule

You walk into a Doutor café, and your initial reaction might be, “Wow, they’re really embracing the 90s retro vibe.” But here’s the catch: for many locations, it’s not a theme. It’s simply… the original design. This represents one of the most intriguing cultural differences for a Western visitor. In the US or Europe, a chain of this scale would undergo a mandatory, system-wide rebranding and renovation every five to seven years to stay “fresh” and “modern.” A design dating from 1998 would be viewed as a corporate misstep, a sign of a brand that’s fallen behind. However, in Japan, a different mindset often dominates. This results in what I call “accidental retro,” a design style born not from nostalgia but from pure, practical necessity.

The Philosophy of “Good Enough” and the Aversion to Constant Renovation

At the core of this phenomenon is a deeply rooted Japanese cultural concept: mottainai. On the surface, mottainai means “what a waste,” but its meaning runs much deeper. It reflects a Buddhist-inspired sense of regret about wastefulness. It’s the belief that everything holds value, and disposing of something before its usefulness is exhausted is almost a moral error. This philosophy permeates Japanese life, from meticulous recycling habits to caring for possessions. It also applies strongly to corporate interior design. From a Japanese business viewpoint, the question isn’t “Does this look outdated?” but rather, “Is it still functional?” Are the chairs broken? No. Is the lighting adequate? Yes. Is the layout efficient for staff and customers? Yes. If so, then spending millions of yen to remove perfectly serviceable furniture and fixtures just to follow a passing design trend feels, well, mottainai.

That’s why you see the particular color schemes that scream Heisei era (roughly 1989–2019): deep burgundies, forest greens, and neutral beiges; brass or gold-toned metal railings and fixtures; medium-stain wood veneers; durable but unremarkable tile floors. These were standard, high-quality, neutral corporate design choices of their time. They were built for longevity, not trendiness. And because they have endured, they remain untouched. The effect is that stepping into one of these Doutor locations is like opening a time capsule. You are witnessing an authentic artifact of late 20th-century Japanese commercial design, preserved not out of retro fashion, but through profound practicality and a reluctance to waste. It’s a subtle challenge to the relentless pace of consumer culture.

The Salaryman’s Refuge: Designed for Function, Not Instagram

To truly appreciate the design, you need to understand who it was intended for. For decades, the backbone of Doutor’s clientele was the Japanese office worker—the salaryman. The space’s design is a masterclass in addressing their particular, unspoken needs. The goal was never to create a social hotspot or an Instagram-worthy backdrop. It aimed to offer a functional, comfortable, and unobtrusive space for individuals to take a brief break.

Look at the layout. You’ll notice many small, two-person tables. This is intentional. It allows solo customers—the vast majority of weekday patrons—to use a space without feeling guilty about occupying a large four-person table. You’ll often see subtle dividers between seating areas, sometimes just a pane of frosted glass or a strategically placed planter. This is not for decoration; it creates a psychological sense of personal space in a crowded room, letting customers feel secluded without isolation. The seating strikes the right balance. Chairs are comfortable enough for a 30-minute break but aren’t plush, sink-into-them armchairs that encourage lingering for hours with a laptop. They are task-focused: sit, drink, read, rest, leave. Even the lighting, which may seem harsh and overly bright to Westerners used to moody, atmospheric specialty cafés, serves a purpose. It’s designed for reading—whether a newspaper, work documents, or a paperback. It’s functional rather than atmospheric. For years, many Doutor cafés dedicated a significant portion of space to smoking areas, often separated by glass walls. Though these have been phased out due to national smoking laws, their legacy shapes the shop’s layout and its historical role as a place where office workers could enjoy coffee and a cigarette—the twin essentials of a corporate break. The entire environment functions like a finely tuned machine, engineered to offer a moment of respite and rejuvenation for the foot soldiers of the Japanese economy.

Finding Your Vibe: A Typology of Retro Doutors

Not all Doutor cafés are created equal. The chain’s true brilliance lies in its subtle ability to adapt to its environment. While the fundamental principles of practicality and affordability endure, each location reflects the unique character of its neighborhood. For experienced travelers in Japan, learning to recognize these nuances is like mastering a new language. You can often anticipate the vibe of a Doutor just by its position on a map. Let’s explore the main archetypes.

The Showa Ghost: Doutor in Historic Districts

Found in: Jinbocho, Kanda, Asakusa, Yanaka, or any area that has aged gracefully, resisting the relentless wave of redevelopment.

The Atmosphere: These Doutors reside in neighborhoods with a strong, independent identity, often linked to a particular trade or history. Jinbocho, Tokyo’s famous book town, is a prime example. Stepping into the Doutor here feels different—quieter, more reflective. The color scheme leans darker—more wood, richer reds, and softer, golden lighting. It’s less of a quick stop and more an extension of the neighborhood’s soul. The patrons tell the story: university professors surrounded by stacks of books, editors marking manuscripts, and elderly locals who have returned to the same seat for decades. The pace is slow; no one is in a hurry. The clatter of keyboards gives way to the gentle rustle of pages turning. This Doutor serves not just coffee but sanctuary for the intellectual and creative heart of the community. It has absorbed the area’s history. You can almost sense the presence of countless students, writers, and thinkers who used this very space to inspire their work and escape life’s pressures. The furniture, though from the Heisei era, here feels less like uniform corporate stock and more like a beloved, well-worn sweater. These “Showa Ghost” Doutors symbolize stability. In a city that reinvents itself every decade, they are anchors, offering a comforting sense of continuity to locals. They remain unchanged because the neighborhood values them that way. Their resistance to change is their greatest charm.

The Heisei Hub: Doutor at Urban Centers

Found in: Shinjuku, Shibuya, Ikebukuro, Tokyo Station, or any major transport hub.

The Atmosphere: Here, Doutor operates in full utility mode. These locations are busy, high-turnover hubs that serve as vital infrastructure for city commuters. The energy contrasts sharply with the quiet Jinbocho branch. It’s controlled, buzzing chaos. The soundscape hums with muted conversations, espresso machine hiss, and train station announcements. The crowd is a cross-section of Tokyo life: shoppers taking a brief pause from retail battles with bags at their feet, nervous students in recruitment suits rehearsing notes for interviews, couples meeting before movies, and salarymen grabbing quick coffee before returning to work. This Doutor exemplifies the Japanese concept of the “third place,” a temporary private bubble within a bustling public arena. Amid millions of people, a small table here becomes your personal island—a place to lower your psychological defenses, stare into your phone, read, or simply zone out in anonymous solitude. It offers a moment of honne (inner truth) in a society that demands constant tatemae (public performance). It’s a vital pressure valve for Tokyo. Watching the silent, intricate dance of customers finding seats, ordering, and leaving reveals a lesson in Japanese social etiquette. There’s an unspoken efficiency, a shared understanding that this temporary resource is to be used responsibly before passing it on.

The Suburban Oasis: Doutor as Neighborhood Living Room

Found in: Jiyugaoka, Kichijoji, Shimokitazawa, or residential areas along suburban private rail lines.

The Atmosphere: Step off the train into a quiet residential neighborhood and encounter a local Doutor, and you’ll notice another shift. The vibe is relaxed, bright, and communal. The frenetic energy of transport hubs gives way to a gentle, friendly hum. This Doutor functions as the neighborhood’s living room. The patrons are primarily locals: groups of “obasan” (affectionate term for older ladies) sharing weekly gossip over baumkuchen; high school students ostensibly studying but mostly chatting and enjoying freedom outside home; young mothers meeting for a rare hour of adult conversation; freelancers using the space as their local office. The staff often recognize regulars, greeting them with nods or smiles. The pace is unhurried. People linger longer. The relentless clock ticking in the Shinjuku branch is much quieter here. This Doutor highlights a key aspect of Japanese social life: with often smaller homes and less frequent home visits than in the West, these affordable, neutral third spaces are essential for fostering community. They are stages for the small dramas of daily life, safe, reliable, and accessible venues where people connect, combat loneliness, and nurture social bonds. They are as crucial to neighborhood health as local parks or libraries.

The Uncanny Valley: The “New” Retro Doutor

Found in: Newly opened shopping malls, redeveloped office buildings, or renovated older locations.

The Atmosphere: This one feels different. You see the familiar green and yellow Doutor logo, spot Milan Sandwiches on the menu board, but upon entering, something feels off. The once-burgundy velour is replaced by light wood and minimalist chairs. Lighting is warm and atmospheric, featuring trendy Edison bulbs. The space is open and airy. It’s pleasant, clean, modern—but completely soulless. This is the Uncanny Valley Doutor, a brand wrestling with its identity in the 21st century. It’s a direct response to fierce competition from Starbucks, Tully’s, and the rise of independent specialty coffee shops. The company recognizes the need to evolve to attract a younger, design-savvy crowd. Yet in doing so, it risks alienating loyal longtime customers who cherish Doutor because it isn’t trendy. These revamped stores serve as fascinating social experiments, raising questions about authenticity and change. Can a brand founded on unpretentious reliability smoothly pivot to being cool and modern? Or does it lose the essence that made it special? Visiting one after spending time in a classic location is jarring—it makes you appreciate the accidental retro charm of older branches even more. It proves the old decor wasn’t random; it was a tangible expression of the brand’s soul.

The Doutor Menu: A Masterclass in Unpretentious Reliability

The story of Doutor is not only conveyed through its interiors but also written into its menu. The food and drink offerings perfectly embody the brand’s core philosophy: quality, consistency, and a deep appreciation of the Japanese palate. The menu has remained remarkably stable over the years, serving as a comforting island of predictability amid ever-shifting food trends.

The Blend Coffee: The Foundation of Consistency

Starting with the coffee itself, Doutor is not a third-wave coffee shop. You won’t find a barista eager to discuss the tasting notes of a single-origin Geisha bean from Panama. That’s not the focus. The signature “Blend Coffee” is the heart and soul of the brand. It is a meticulously crafted, mass-produced product designed with one goal in mind: consistency. Usually a medium-dark roast with low acidity, it offers a balanced, straightforward coffee flavor. It’s smooth, dependable, and tastes exactly the same at over 1,000 locations nationwide. Among coffee aficionados, it might be labeled “boring,” but that misses the point entirely. The Doutor Blend is like the Toyota Corolla of coffee. It’s unflashy and unlikely to win design awards, yet it’s impeccably engineered, incredibly reliable, and consistently performs perfectly. This commitment to quality control at scale reflects a hallmark of Japanese industry, which Doutor applies expertly to coffee. For the millions who drink it daily, its predictable, comforting flavor isn’t a flaw—it’s its greatest feature.

Beyond Coffee: The Milan Sandwich and Baumkuchen

Where Doutor’s quiet brilliance truly stands out is in its food menu. It offers a small, carefully curated selection of items that focus on reliability. The undisputed star is the “Milan Sandwich.” Served on a long, crusty roll that falls somewhere between a baguette and a soft hot dog bun, it exemplifies simplicity. The classic “Milan Sandwich A,” featuring uncured ham and green beans, is a masterclass in texture and flavor balance. It’s not an overstuffed, greasy deli sandwich but light, fresh, and precisely assembled, with every ingredient chosen intentionally. The sweets menu is equally iconic. You won’t find trendy cronuts or elaborate cakes here. Instead, it features Japanese café classics, often European pastries adapted and perfected for local tastes. The Mille Crepe cake, with its numerous layers of delicate crepes and light cream, remains a perennial favorite. The Baumkuchen, a German layer cake, is another staple, cherished for its simple, satisfying flavor and moist texture. This menu is pure comfort food, evoking nostalgia for many Japanese customers—a taste of their youth or early working years. In an environment where food trends rapidly come and go, Doutor’s menu is a steadfast anchor. You can walk in today and order the exact same Milan Sandwich you enjoyed a decade ago, and it will be just as good. This isn’t complacency; it’s a deliberate, powerful brand promise of stability and comfort.

The Social Contract of a Doutor Seat

To truly grasp Doutor, you must first understand the invisible rules that shape its social environment. For newcomers, some of these behaviors can be quite perplexing. However, once you comprehend the underlying social contract, the system’s elegance and efficiency become clear. It represents a microcosm of Japanese society, founded on high trust and mutual respect.

The Art of “Datsu” (Claiming a Spot)

Here’s a scenario that might baffle a Westerner: a person enters a busy Doutor, looks around for an empty table, walks over, places their handbag (or phone or laptop) on a chair to reserve it, and only then goes to the counter to order coffee. In many other countries, this could invite theft. In Japan, it’s a normal practice. This seat-claiming act is known informally as 席取り (sekitori), relying on an extraordinary level of social trust. The unspoken agreement is that a reserved seat is inviolable and personal items are safe. This system prioritizes efficiency and reduces anxiety. Instead of carrying a tray of hot coffee around in search of a seat, you first secure your spot, then order calmly. Though small, this custom reveals the foundational assumption of honesty and respect underlying public life in Japan. Such a system simply couldn’t function in a low-trust society.

The Invisible Clock: When Is Too Long?

Once seated, another invisible rule takes effect: the social clock. While there are no official time limits, a strong, unspoken understanding discourages overstaying, especially during busy times. This is guided by 空気を読む (kuuki wo yomu), literally “reading the air.” It means sensing the social context and adapting your behavior accordingly. If the café is crowded and people are searching for seats, you feel a subtle pressure to finish and leave. This pressure doesn’t come from staff—they rarely ask anyone to go—but from the atmosphere and collective mood. It stems from 思いやり (omoiyari), a deep sense of consideration for others. Your wish to linger is balanced against the group’s needs. You implicitly accept that the seat is a shared community resource. This sharply contrasts with the “laptop nomad” culture of many Western cafés, where buying a single coffee is treated as rental for a workspace all day. At Doutor, the agreement is different: it’s a place for a break, not an office. Recognizing and respecting this invisible clock is essential to blending into the café’s social fabric.

Why Doutor Endures in the Age of Cool Coffee

In a world dominated by artisanal roasts, minimalist design, and Instagram-fueled cafe culture, how does a chain like Doutor not just survive but flourish? The answer lies in the fact that Doutor isn’t running the same race. It’s not selling “cool.” Instead, it offers something far more valuable and lasting: comfort, reliability, and a refuge from the pressures of modern life. In its own subtle way, it stands as a form of rebellion—an antidote to the performative atmosphere of many contemporary public spaces. You don’t visit Doutor to be noticed or to snap a photo of latte art. You go there to fade into the background, to become anonymous, and to enjoy a quiet moment with your thoughts, free from judgment or expectation.

Doutor embodies a large, often overlooked segment of Japanese society that prioritizes practicality over showiness, and consistency over novelty. It reminds us that beneath Japan’s futuristic, trend-setting exterior lies a deep respect for the simple, the functional, and the familiar. For repeat visitors eager to understand Japan beyond the typical tourist experience, appreciating Doutor is like unlocking a new level of cultural insight. It means finding beauty in the everyday, discovering depth in the practical. It’s a realization that a nation’s story is not only told through its grand temples and gleaming skyscrapers but also in the quiet corners of its most ordinary coffee shops. Next time you’re in Japan, skip the trendy cafe once. Seek out a Doutor with its worn velour seats, order a simple blend coffee and a Milan sandwich, and just sit. Watch. Listen. Read the atmosphere. You may discover that this unassuming, slightly old-fashioned coffee shop is the most authentic spot in the entire city.