Hey everyone, Sofia here! Let’s spill the tea on one of Japan’s most baffling and low-key epic features. You’ve just arrived in a major Japanese city—Tokyo, Osaka, you name it. You’re trying to find the entrance to the ‘A3’ subway exit, but you descend a random staircase and—BAM. You’re not just in a station. You’re in a whole other city, but it’s underground. Endless corridors of shops, restaurants, and rivers of people stretch out in every direction under a sky of fluorescent lights and ceiling tiles. You walk for ten minutes, thinking you must be close to your destination, only to realize you’ve surfaced half a kilometer from where you started, probably inside the basement of a department store you didn’t even know was there. If you’ve ever felt like you’ve accidentally noclipped into the backrooms of a Japanese metropolis, you’ve stumbled into a ‘Chikagai’ (地下街), or underground shopping street. It’s a vibe, for sure, but it’s also legit confusing. It’s not quite a mall, not just a train station passage… so what is it? Why does Japan have these sprawling subterranean worlds? Is this just what happens when you run out of space on the surface? The answer is a wild mix of history, hardcore pragmatism, and a unique urban philosophy. It’s not just about saving space; it’s about conquering time, weather, and the general chaos of life itself. These concrete labyrinths are one of the best-kept secrets to understanding the rhythm of modern Japanese life. So grab your comfiest walking shoes, and let’s get lost together as we decode the logic behind Japan’s underground obsession. It’s gonna be a trip, literally.

This pragmatic, weather-defying approach to urban design is part of a broader national fascination with functional concrete spaces, much like the surprisingly complex world of Japan’s roadside rest stops.

The Phoenix from the Ashes: How War and Railways Forged the Underworld

To truly understand why these underground cities exist, you need to rewind the clock. This is not a futuristic sci-fi concept; it is a direct outcome of Japan’s turbulent 20th-century history. The story begins amid the smoldering ruins of World War II. Major cities like Tokyo and Osaka were firebombed into oblivion, leaving a landscape reduced to rubble. When the time came to rebuild, the process was rapid, chaotic, and driven by an urgent need to revive the economy. There was no room for grand, Parisian-style master plans. The approach was one of ‘scrap and build’—whatever worked, worked now. Surface space was instantly scarce, and land ownership was a complicated patchwork.

Meanwhile, another force shaped the future of urban Japan: the railways. Unlike many Western countries where the car became dominant, in Japan, trains remained the unrivaled kings of transportation. Here’s the twist: many railway lines were privately owned. Companies such as Hankyu, Tokyu, and Seibu weren’t just focused on moving people; they were experts in creating destinations. Their strategy was brilliant. They built railway lines extending to the suburbs, then erected massive, glamorous department stores atop their main city terminals. You’d ride their train and shop at their store. This synergy gave rise to a new kind of urban center—the train station complex.

As these stations expanded, they grew increasingly intricate. One station might serve a national JR line, two private railway lines, and three subway lines, each operated by different companies. To connect them all, underground passages became the only practical solution. Tunnels were constructed to link platforms and station buildings. Initially, these were bare, utilitarian corridors meant only to channel the flow of people. But where there are people, commerce inevitably follows. Small vendors, spotting an opportunity, began setting up shop—tiny stalls selling newspapers and cigarettes, stand-up noodle bars for quick meals between transfers, shoe-shine stands. This development wasn’t planned; it grew organically, almost parasitically. The passages were arteries, and these small shops were the cells that clung to them, thriving on the constant stream of commuters.

The first officially designated Chikagai, Nanabanchikagai, appeared in Tokyo’s Ueno station area in the early 1930s, but the concept truly exploded during the post-war high-growth period of the 1950s and 60s. As cities modernized, these informal underground markets were formalized, expanded, and evolved into the sprawling networks we see today. For example, Tokyo Station’s Yaesu Chikagai opened in 1965, just a year after the first Shinkansen bullet train began operating from the same station. It symbolized the new Japan: efficient, modern, and relentlessly focused on economic activity. The Chikagai didn’t emerge from a single ingenious idea but evolved as a practical response to the unique historical and economic pressures of post-war Japan. It’s a city built on the foundations of recovery, powered by the ambitions of private railways, and sprawling into the complex organism we witness today.

The Weatherproof Bubble: Japan’s Ultimate Life Hack

Alright, so history explains the origin, but what accounts for the vast scale and ongoing importance of Chikagai? Two words: the weather. If you believe Japanese weather consists only of peaceful cherry blossoms and calm autumn leaves, prepare for a surprise. The reality is a harsh climate that can be extremely unpleasant. Summers are oppressively hot and humid, with temperatures soaring and moisture sticking to you like a second skin. This season is also marked by typhoons, intense storms that bring heavy rain and powerful winds, shutting down the city. Then there are the ‘guerrilla downpours’ (ゲリラ豪雨, gerira gōu), sudden, localized flash floods that can soak you in seconds. Winters, particularly in northern cities, can be biting cold with snow and ice. Spring and autumn are pleasant, but brief.

Now, picture yourself as a ‘salaryman’ or ‘office lady’ in Osaka. Your daily commute involves a ten-minute walk to the station, taking two different train lines, then another five-minute walk to your office. Doing this in mid-August means arriving at work drenched in sweat. During a typhoon, it means struggling against sideways rain with an umbrella sure to be destroyed. It’s inefficient, uncomfortable, and a daily source of stress.

Enter the Chikagai. It is, quite simply, the ultimate climate-controlled haven. It’s an architectural response to an environmental challenge. From the moment you descend the stairs near your apartment, you enter a world where the weather disappears. The temperature is a constant 22 degrees Celsius. The air is dry. There’s no wind, rain, or snow. You can walk from your local subway station, transfer to a JR line, and enter the basement of your office building without stepping outside once. The Japanese have a phrase for this highly sought-after feature, often used in real estate ads: ‘nurezu ni’ (濡れずに), meaning ‘without getting wet.’ Being able to get from the station to work ‘nurezu ni’ is a major selling point and a significant quality-of-life improvement.

This creates a distinctive daily rhythm for millions of city residents. Imagine this: you leave your apartment and enter the Chikagai. You grab a coffee and a pastry for breakfast from a bakery below. You navigate the corridors to your office. At lunchtime, you don’t go outside; you and your coworkers simply return to the basement and choose from dozens of quick, affordable eateries—ramen, curry, katsu, soba. Need to run an errand? The post office, an ATM, and a drugstore are all within a five-minute walk, still inside the bubble. After work, you meet friends for a quick drink at a ‘tachinomi’ (standing bar) in the Chikagai before heading to your train platform to go home. In this scenario, it’s entirely possible to go through a whole workday without seeing the sun or breathing fresh air. It might sound a little dystopian, but from a practical standpoint, it’s incredibly efficient. The Chikagai isn’t just a shopping center; it’s essential infrastructure that removes the unpredictability and hassle of the natural world from daily life.

Welcome to the Dungeon: Anarchy by Design?

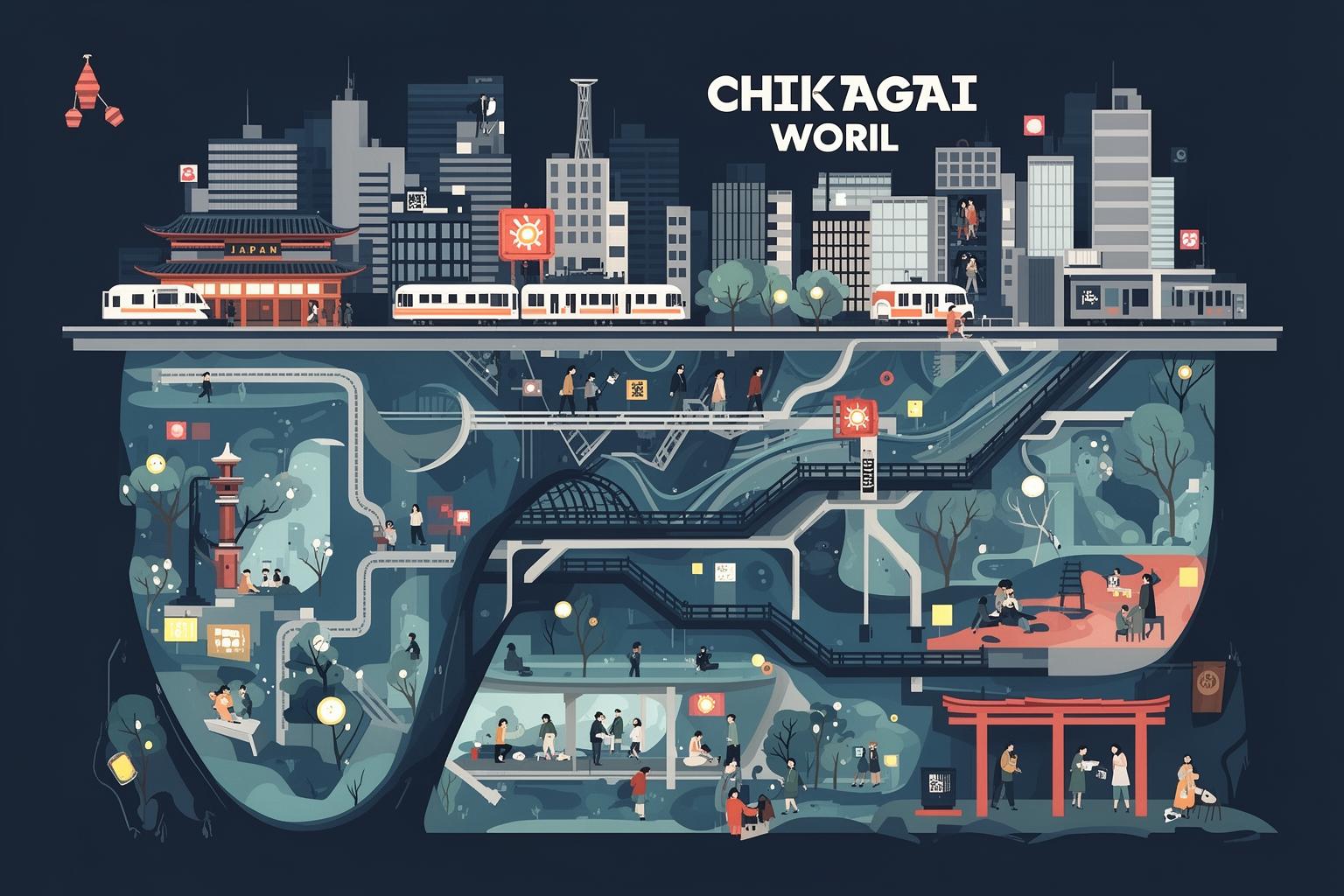

So, you’ve acknowledged the existence and purpose of the Chikagai. Now, the next challenge awaits: navigating it. For first-timers—and honestly, even for locals—this is where things become truly wild. Areas like the underground network around Osaka-Umeda Station are legendary, affectionately (and fittingly) dubbed the ‘Umeda Dungeon.’ Trying to find your way using a map is often pointless. The layouts defy logic, corridors twist unpredictably, and staircases lead to unexpected places. So, why is it so bewilderingly confusing?

The answer lies in its chaotic, incremental development. A Chikagai isn’t a single building; it’s an ecosystem that has evolved over decades, layer upon layer, like a concrete coral reef. It was never designed with one unified master plan. Picture a simple underground passage created in the 1960s to connect the JR station to the new Hankyu department store. A decade later, a subway line is added, with a new tunnel connecting to the existing passage. Then, a new office building rises nearby, and its developers arrange to link their basement to the expanding network. Another department store does the same. Each addition was built according to the engineering constraints, property lines, and corporate interests of its own time. The result is a patchwork of different architectural eras stitched together. You can literally see the history as you walk: floor tiles change suddenly from 70s terrazzo to 90s polished granite. Ceiling heights drop, lighting shifts from warm fluorescent to cool LED. Signage fonts and styles change completely. You’ve just crossed an invisible boundary from an area managed by the city’s transport bureau to one owned by a private railway conglomerate.

This patchwork of ownership is central to the confusion. Different sections of the same continuous underground space are controlled by different entities. Whity Umeda, Diamor Osaka, and Hankyu Sanbangai all form part of the Umeda Dungeon, yet they are separate commercial entities with distinct branding, directories, and logic. That’s why following signs can feel like a nightmare. You might be following directions for the Yotsubashi Subway Line, but the moment you step into another “territory,” those signs vanish, replaced by ones highlighting local landmarks such as the Daimaru Department Store.

Locals don’t navigate using maps or grids. They rely on landmarks and muscle memory. “Go past Tully’s Coffee, turn right at the statue of the funny-looking dog, and take the third staircase on your left.” It’s a kind of tribal knowledge. Getting lost is almost a rite of passage—a sign you’re truly interacting with the city. The apparent chaos isn’t a design flaw; it’s proof of a living, breathing city that’s constantly evolving. It’s the physical embodiment of decades of backroom deals, engineering hurdles, and shifting commercial priorities, all buried just a few meters beneath the asphalt. In its own way, it perfectly reflects the organized chaos of the Japanese city above.

The Chikagai Vibe Check: What’s Actually Down There?

If you’re expecting the glitz and glamour of a luxury shopping mall, you might want to temper your expectations. While some modern Chikagai connected to high-end office buildings can be sleek and stylish, the classic Chikagai atmosphere is quite different. It’s less about aspirational luxury and more about raw, unpretentious functionality. It serves as a space for people in transit, workers on their lunch breaks, and purposeful commuters. The aesthetic often takes a backseat to practicality. Picture low ceilings, sometimes exposing pipes and ductwork. Imagine the harsh, shadowless blaze of fluorescent lights. Envision endless corridors lined with durable, repetitive floor tiles designed for easy foot traffic. It’s an environment that can seem sterile, outdated, and a bit claustrophobic. It’s a non-place, a pure conduit of transit. Yet, within this utilitarian shell, a lively and specific business ecosystem thrives.

The Culinary Underworld: Fueling the City

At the core of any Chikagai is its food scene. It’s not about Michelin stars; it’s about speed, value, and convenience. The food offerings are finely tuned to meet the demands of the local population.

Lunch Rush Havens

Come weekday noon, the Chikagai becomes a feeding ground for city office workers. The dominant establishments are restaurants specializing in ‘fast’ Japanese food. Think ramen shops where you buy a ticket from a vending machine, hand it to the chef, and within five minutes have a steaming bowl of noodles before you. Often, you’ll eat at a counter, shoulder-to-shoulder with other lone diners, all efficiently slurping down their lunches before returning to work. Curry rice stands, soba and udon noodle shops, and katsudon (pork cutlet bowl) places operate on the same high-volume, high-speed service principle. It’s a fascinating dance of urban efficiency.

The After-Work Oasis: Tachinomi Bars

As evening descends, a different kind of venue comes alive: the ‘tachinomi’ (立ち飲み), or standing bar. These are typically small, no-frills spots, often just a counter, where colleagues or friends gather for a quick, inexpensive drink and some snacks before catching their trains home. There are no chairs; you stand, drink, and chat. The atmosphere is lively, warm, and communal. It’s a liminal space between the formal office world and the privacy of home—a place to unwind with a cold beer and some yakitori skewers. It offers a raw, authentic slice of Japanese work culture.

Kissaten & Modern Cafes

You’ll also discover an intriguing layering of coffee culture. Scattered throughout the network are modern chain cafes like Starbucks and Doutor, providing a familiar, clean space for a quick caffeine boost or remote work session. But if you look closely in the older, more neglected corners of a Chikagai, you might find a ‘kissaten’—a traditional Showa-era coffee house. These are time capsules, often featuring vinyl booths, smoky air (though less so nowadays), and a stern but dedicated owner brewing siphon coffee. They serve as quiet refuges for older patrons, venues for discreet meetings, or simply places to escape the relentless corridor flow for a moment of calm reflection.

A Bazaar of Daily Needs

Beyond food and drink, the Chikagai is a one-stop shop for life’s everyday errands and emergencies. The retail mix is highly practical.

The Pharmacy Universe

Japanese drugstores are worlds unto themselves and are foundational to the Chikagai ecosystem. They carry everything from prescription medicine and bandages to high-end cosmetics, cleaning supplies, snacks, and beverages. For office workers, it’s the ideal spot to grab throat lozenges, hangover remedies, or a replacement pair of stockings during lunch.

Services for People on the Go

Services cater to the commuter’s needs. You’ll find shoe repair and shining stalls that can fix a broken heel in ten minutes, key cutters, small post office counters for mailing letters, and shops offering quick clothing alterations. Lottery booths draw long lines at certain times of the year, and you might even spot a fortune teller’s stall tucked away in a quiet corner, providing guidance to those seeking answers amid the chaos.

Fashion for the Masses

Clothing stores in a typical Chikagai aren’t high-fashion boutiques. They address the immediate needs of their customers. Shops sell affordable business shirts, ‘office casual’ attire, comfortable shoes, as well as plenty of socks and umbrellas. Fashion here is functional—if you spill coffee on your shirt before an important meeting, the Chikagai has an inexpensive and practical replacement ready.

The Mind in the Cave: Social and Psychological Dimensions

Living within and navigating these extensive underground networks subtly yet profoundly influences the urban psyche. The Chikagai is more than merely a set of shops and passageways; it is a controlled environment that shapes behavior and perception. Entering one feels like stepping into a bubble where the outside world fades away. There is no day or night, no rain or sunshine. The passage of time is marked solely by the ebb and flow of crowds—the morning rush, the lunchtime surge, the evening departure. This complete disconnection from the natural environment can provide both comfort and unease. On one hand, it offers predictability and stability in an often chaotic world. On the other, it may seem deeply artificial and claustrophobic, akin to a sensory deprivation tank on a city-wide scale.

This represents the ultimate expression of a central theme in Japanese urbanism: prioritizing efficiency and order. The Chikagai is a perfectly engineered system designed to move people from Point A to Point B with minimal friction. The wide corridors, clear (if sometimes confusing) signage, and seamless integration with public transport all aim to maintain a steady, uninterrupted flow. The individual’s experience is secondary to the smooth operation of the collective system. You become a particle in a human river, and the architecture serves as the riverbed, guiding you along a predetermined course. This philosophy sharply contrasts with, for example, the European ideal of the city square or the winding medieval street, which encourage lingering, serendipity, and wandering without purpose.

When compared to underground networks elsewhere in the world, Japan’s Chikagai stand out for their uniqueness. Montreal’s RÉSO and Toronto’s PATH offer functionally similar, climate-controlled links between buildings, but the Japanese Chikagai differ greatly in scale and, critically, in their full integration with the railway system. The train station acts as the heart, while the Chikagai function as arteries pumping life, commerce, and people directly into the city’s core. They are not simply connectors; they are destinations in their own right, intricately woven into daily social and economic life in a way unmatched elsewhere.

Yet, this hyper-efficient, weatherproof world has its detractors. Some urban planners and sociologists contend it fosters disconnection from the local community and the natural environment. By allowing people to bypass above-ground streets, it can hollow out surface businesses and sanitize the urban experience, removing the chance encounters and unexpected discoveries that enliven city life. It promotes living in transit, moving through a series of privatized, commercialized non-places—the train, the station, the Chikagai, the office building. It operates as a perfectly efficient machine for modern life, but one must wonder what is lost when you never have to feel the rain on your face.

Is It Worth the Hype? How to Explore the Real Underground Japan

So, after all of this, we arrive at the key question for any traveler: is it truly worth going out of your way to explore a Chikagai? Is it a valuable tourist experience? The answer is a definite ‘it depends on what you’re seeking.’ If your image of Japan revolves around ancient temples, tranquil gardens, and idyllic Ghibli-inspired scenes, then a Chikagai will likely disappoint. It is generally not scenic. There are no ‘wow’ moments for your Instagram. The lighting is harsh, the scenery repetitive, and the atmosphere overwhelmingly ordinary.

However, if you’re the type of traveler genuinely interested in how modern Japan functions—if you want to glimpse behind the facade of polite society and witness the mechanisms that keep these mega-cities running—then a Chikagai is an absolutely essential, non-negotiable experience. It’s a living museum of urban sociology. Don’t go there to just ‘see’ things. Go there to observe. Watch the clockwork precision of the lunch rush. Notice the subtle social cues in the tachinomi bars. See how different generations occupy the space in varied ways. It’s an anthropological deep dive into the rhythms, priorities, and pressures of everyday Japanese life.

To get the most out of it, it helps to understand what type of Chikagai you’re entering. Think of them as archetypes:

H3: A Chikagai Field Guide

H4: The Labyrinth (e.g., Umeda in Osaka, Shinjuku in Tokyo)

This is the archetypal Chikagai experience. Huge, sprawling, and bewilderingly intricate, these are the legendary ‘dungeons.’ Visit if you want to feel the overwhelming scale of an underground city. Don’t try to master it; just let yourself get lost. Follow the flow and see where you end up. It’s an adventure in urban disorientation.

H4: The Corporate Corridor (e.g., Yaesu at Tokyo Station, Otemachi)

These tend to be newer, cleaner, and more linear. They link major business areas and feature somewhat upscale cafes and restaurants catering to office workers. The atmosphere is less chaotic and more purposeful. This is the Chikagai as a seamless office extension.

H4: The Retro Time Capsule (e.g., parts of Nagoya’s Sakae network, Fukuoka’s Tenjin)

In some cities, you can find older Chikagai sections that seem frozen in the 1970s. These are the places to discover old-fashioned kissaten, quirky small shops, and a more laid-back, local vibe. They offer a nostalgic glimpse into Japan’s economic boom era.

H4: The Pop Culture Hub (e.g., Tokyo Station’s ‘Character Street’)

This showcases the modern evolution of the Chikagai concept. Here, the utilitarian passage has been turned into a themed attraction. Tokyo Station’s Character Street is lined with official stores for Hello Kitty, Pokémon, Studio Ghibli, and various anime characters. It’s a brilliant blend of transit infrastructure and commercial pop culture, and a must-visit for fans.

My final advice? Don’t view the Chikagai as a destination. Use it as intended: a passageway. When moving from a train station to a department store, or from one subway line to another, opt for the underground route. Let it be part of your journey. Pay attention to the details, the people, the sounds, and the smells. This is not the Japan depicted in travel brochures. This is the real thing. The concrete, fluorescent-lit, perfectly climate-controlled heart of the modern Japanese city. And once you tune into its rhythm, you’ll gain a much deeper understanding of Japan itself.