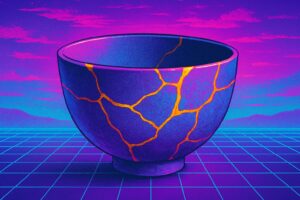

Alright, let’s get into it. You’ve probably seen it on your feed. A picture-perfect, minimalist shot of a ceramic bowl, but it’s got these crazy, beautiful cracks running through it, all filled with shimmering gold. It looks luxe, it looks deep, it looks… kinda weird? Your first thought might be, “Cool, but why?” Why would anyone take a broken pot, something you’d normally just chuck in the bin, and not only fix it but highlight the damage with actual gold? Isn’t that like putting a neon sign on a mistake? It’s a total vibe, for sure, but it feels like a paradox. In a world obsessed with flawless filters, brand-new drops, and out-of-the-box perfection, this Japanese art of Kintsugi is giving main character energy in the complete opposite direction. It’s not about hiding the flaws; it’s about making them the whole entire point. And if you’ve ever looked at Japan and thought, “I love it, but I don’t quite get it,” then Kintsugi is low-key the perfect key to unlocking the whole mindset. It’s way more than just a boujee repair technique. It’s a philosophy, a history lesson, and a whole new way of looking at what it means for something—or someone—to be beautiful, strong, and complete. So, let’s spill the tea on why mending with gold isn’t just about aesthetics; it’s about an entire worldview that celebrates the journey, scars and all. It’s time to understand the maker’s mindset behind this golden glow-up.

This mindset of valuing the process and the maker’s intent is deeply connected to the Japanese philosophy of mono-zukuri.

The Vibe Check: What Even IS Kintsugi?

Before we dive into the philosophical depths, let’s first break down what we’re actually looking at. The word itself is quite straightforward if you split it apart. ‘Kin’ (金) means gold, and ‘Tsugi’ (継ぎ) means joinery or to join. Put together, they form ‘Kintsugi’ (金継ぎ), or “golden joinery.” It’s exactly what it sounds like. But it’s not just about slapping some gold adhesive on a broken mug from your kitchen cabinet. This is an authentic, traditional Japanese craft that demands serious skill and patience. The entire process revolves around a very special, highly traditional material: urushi lacquer. Urushi is the original superglue, derived from the sap of the Chinese lacquer tree. It’s no joke; it’s incredibly durable, waterproof, and can cause a severe rash if it touches your skin before curing. It has been used in Japan for thousands of years for everything from decorating furniture and crafting bento boxes to waterproofing samurai armor. In Kintsugi, urushi lacquer is the heart of the process. The artisans mix it with other natural ingredients like clay powder or rice flour to create a putty that they carefully use to piece the broken fragments back together. Once the pieces are joined, the waiting begins. Urushi doesn’t “dry” like paint; it cures. It requires a very specific warm, humid environment to harden properly, a process that can take weeks or even months. After the initial bond is solid, the artist applies additional layers of urushi lacquer over the seams to form a smooth, sealed surface. Only then, at the very end, is the gold added. The final, still-tacky layer of lacquer is dusted with superfine powdered gold, silver, or platinum using delicate brushes and tools. The powder adheres to the lacquer, and once fully cured, it is polished to a radiant shine. The result is a network of metallic veins flowing across the ceramic surface, each line marking a moment of rupture and restoration. It’s not a cover-up. It does not pretend the break never happened. Instead, it declares, “This object broke, and it was cared for so deeply that it was restored not just to function but to become more beautiful and intriguing than before.” It’s a complete transformation. The break isn’t the end of the story; it’s the plot twist that makes the story worth telling. The object’s history is now engraved on its surface for all to see, and that history is celebrated as an essential part of its identity. That’s the key difference between Kintsugi and a tube of superglue. One erases the past; the other illuminates it.

The Backstory: A Shogun’s Broken Bowl

The whole concept of glamorizing your broken items didn’t appear out of thin air. Like many things in Japan, it has a history rich in aesthetics, philosophy, and a touch of legend. The most well-known origin story, the one everyone recounts, takes us back to the 15th century during Japan’s Muromachi period. The central figure in this tale is Ashikaga Yoshimasa, a shogun who cared less about politics and war and more about art and culture. A great patron of the arts, his reign is credited with the birth of much of what we now consider “traditional” Japanese aesthetics, including the tea ceremony, flower arrangement, and ink wash painting. According to legend, Yoshimasa owned a cherished celadon tea bowl from China. One day, disaster struck and the bowl broke, much to his dismay—it was his favorite. Naturally, he sent it back to Chinese experts for repair. After a long wait, the bowl returned, but Yoshimasa was appalled. The Chinese craftsmen had “repaired” it using ugly, clunky metal staples. Although functional, the rough metal stitches ruined the delicate beauty of the bowl—it simply wasn’t right. Being a devoted aesthete, Yoshimasa was deeply dissatisfied and challenged his Japanese artisans to find a better way. He wanted a repair that was not only practical but beautiful—one that honored the bowl’s spirit instead of just stapling it together like broken farm equipment. The story goes that Japanese craftsmen, inspired by this challenge and their own aesthetic sense, developed the technique of mending with precious lacquer and powdered gold. They didn’t merely fix the bowl; they transformed it into a new masterpiece. The cracks became a feature to admire—a golden map of the object’s journey rather than a source of shame. Whether historically accurate or not, this tale perfectly illustrates the cultural shift of the time. Japan was moving away from the lavish, perfectly symmetrical Chinese aesthetics toward its own unique beauty: quieter, subtler, and deeply connected to nature and the passage of time. Central to this movement was the tea ceremony, or chanoyu. Tea masters began to favor rustic, imperfect, locally made tea bowls over technically flawless, expensive Chinese wares. They appreciated the subtle asymmetry of hand-thrown pots, the feel of the clay, and the irregular glaze drips. It was in this cultural context that Kintsugi was born, embodying the new aesthetic: a reverence for imperfection, humility, and an object’s history. It declared that an object’s value lies not in flawlessness but in its story, resilience, and the care given to it.

The Philosophical Deep Dive: Wabi-Sabi, Mottainai, and Mushin

Alright, so we’ve covered the what and the when. But to truly grasp Kintsugi, you need to understand the why. That means diving deep into some significant Japanese philosophical ideas. These concepts form the invisible foundation of the entire culture, explaining far more than just the practice of repairing pottery with gold. They reveal the deeper currents of the Japanese worldview. Let’s break it down.

Wabi-Sabi: The Genuine Appeal

This term is likely familiar to you. It’s become a global catchphrase for minimalist style, rustic elegance, and anything that looks aged or weathered. But ‘wabi-sabi’ (侘寂) goes much deeper than a design fad. It’s the core of Japanese aesthetic principles and, frankly, it’s a bit challenging to fully comprehend. It actually merges two separate ideas over time. Let’s examine them one by one. First, Wabi (侘). Originally, ‘wabi’ bore somewhat negative meanings, suggesting loneliness and hardship in remote living. But, influenced by Zen Buddhism, it transformed. It now signifies a quiet, simple, rustic beauty. It’s the charm found in modesty and understatement. It’s about contentment, finding wealth in simplicity, and appreciating the unpretentious. Picture sitting in a plain wooden tea house on a rainy day, listening to raindrops fall—that’s wabi. It embodies serene melancholy and calm acceptance of reality. It’s not about poverty but choosing simplicity over luxury. Then there’s Sabi (寂). This concept emphasizes the beauty of aging. It’s the visible sign of time passing—the patina that forms on an object from use and exposure. It’s the rust on an iron gate, the moss on a stone lantern, the smoothed wood of an old temple floor. ‘Sabi’ reflects a story, proving an item has lived, endured hardships, and touched many lives. It appreciates impermanence and the quiet elegance of decay. Together, Wabi-Sabi forms a worldview. It finds profound beauty in flaws, impermanence, and incompletion. It opposes perfection, teaching that wear and tear aren’t flaws but honorable scars telling a story. How does this relate to Kintsugi? It’s wabi-sabi philosophy made tangible. A crack in a bowl is impermanence made visible. The asymmetrical crack is imperfect. The bowl is incomplete. A Western perspective might say, “It’s ruined, worthless.” But wabi-sabi says, “Now it has history; it has sabi.” Repairing it with Kintsugi is a wabi act—quiet, humble, attentive. The gold doesn’t hide or recreate perfect symmetry; it follows the natural, chaotic crack, honoring rather than concealing damage. Kintsugi is the pinnacle of wabi-sabi, turning a broken, imperfect object into something valid, beautiful, and valuable.

Mottainai: The Shame of Waste

This concept is enormous. Spend any time in Japan and you’ll hear ‘mottainai’ (勿体無い). Kid leaves rice unfinished? Mottainai. Lights left on in an empty room? Mottainai. Throwing out a perfectly good shirt because a button is missing? Classic mottainai. It roughly means “what a waste,” but that’s just scratching the surface. ‘Mottainai’ expresses a deep, instinctive regret about misusing something. It’s not just wasting money; it’s wasting the intrinsic worth of anything. It’s a Buddhist term for sorrow over throwing away what’s been given—food, resources, time, potential, even life. Everything has spirit, life force, purpose, and discarding it prematurely is almost a moral failing. This attitude permeates everyday life in Japan. It’s why people care so meticulously for their belongings, why recycling is so detailed, and why gifts are wrapped with great care—not just respecting the recipient but the gift itself. This is where Kintsugi fits perfectly. To discard a finely crafted ceramic bowl—a product of skill, resources, and time—simply because it broke is the very definition of mottainai. Doing so wastes the artisan’s labor, the earth’s clay, the kiln’s fire, and all the memories tied to that bowl. Kintsugi counters mottainai completely. It’s a profound act of respect, saying, “Your life isn’t over; your worth remains.” It honors an object’s full life cycle, acknowledging its past and offering it a future. By investing time, skill, and precious materials to repair it, you don’t just restore function—you elevate its status. You thank the object for its service and ensure its story endures. It’s the opposite of the modern throwaway culture.

Mushin: The Mind of No Mind

This is a bit more abstract but crucial to understanding both the Kintsugi process and the artisan’s mindset. ‘Mushin’ (無心) is a Zen concept meaning “no mind.” It doesn’t imply emptiness but a state free from distracting thoughts, ego, fear, and anger. It’s fluid awareness where mind and body act as one without conscious effort. Martial artists describe mushin as instinctive reaction in combat; musicians experience it as being lost in the flow of playing. It’s full presence in the moment. For a Kintsugi artisan, mushin is essential. They can’t approach a broken pot with anger or frustration. Ego cannot drive them to force the pot back to its flawless original state. They must accept the object’s current reality: broken. Detachment from its prior perfection is necessary. Kintsugi is slow, meditative work demanding intense focus. The artisan works with the cracks, not against them. They don’t impose their will but collaborate with the pot’s new form. They embrace damage as part of its journey, discovering a new path forward. This calm, non-attached acceptance is mushin. It involves seeing breaks not as failures but as events that happened. The artisan responds with care, skill, and creativity. This Zen acceptance transforms the repair into an act of beauty, elevating the craft from mere restoration to active meditation—a dialogue between artisan and the object’s history.

Kintsugi in Practice: Not Just a Glue Gun and Some Glitter

So, you’ve admired the aesthetic and embraced the philosophy, and now you’re thinking, “I could definitely try that on the mug I broke last week.” Hold on a second. Although DIY Kintsugi kits are everywhere online, it’s crucial to realize that the traditional method is on a completely different level. It’s a serious, time-intensive craft that demands a great deal of skill and some rather specialized materials. This isn’t just a casual weekend project; it’s a serious commitment. Let’s go through the meticulous steps a true artisan follows, so you can truly appreciate the dedication involved. First, you gather all the broken pieces—every shard, no matter how tiny, is carefully collected. Then, each piece is thoroughly cleaned to remove any dust, oil, or debris that could interfere with adhesion. This is the starting point. Now comes the real magic: the urushi lacquer. The artisan begins by making a binding lacquer called mugi-urushi, a mixture of raw urushi sap, water, and either rice or wheat flour, blended into a sticky, strong adhesive paste. This paste is precisely applied to the edges of one of the broken fragments. It needs to be just right—too little won’t bond, too much will squeeze out and create a mess. The matching piece is then pressed firmly against it, and the artisan works carefully to ensure a perfect fit. The pieces are held in place with tape or clamps and left to start the lengthy curing process. This is where the muro comes into play—a humidity chamber, often a simple wooden or cardboard box. Urushi lacquer is delicate and requires a specific environment to cure properly, usually around 70-85% humidity and temperatures between 20-30°C. Under these conditions, an enzyme in the sap polymerizes, turning the sticky liquid into a hard, durable, and waterproof solid. This first bonding stage alone can take one to two weeks. After the main sections are joined and solidified, the work continues. What about the tiny chips and gaps? For these, the artisan crafts a different putty called sabi-urushi, a blend of urushi and super-fine clay powder (tonoko), resulting in a thick, clay-like filler. The artisan painstakingly fills each chip, crack, and void with this putty using a fine spatula, applying it in thin layers. Each thin layer must be cured again in the muro, often taking several days. After curing, the layer is sanded smoothly using charcoal or fine sandpaper, then another layer is added. This cycle of filling, curing, and sanding may be repeated dozens of times, stretching over weeks or even months, depending on the damage. The aim is to create a new surface perfectly flush with the original ceramic. Once all the gaps are filled and the surface is flawlessly smooth, the artisan applies a layer of colored urushi over the seams, usually red or black lacquer, which acts as an undercoat for the gold. This layer must also be cured and polished. Finally, after all this patient and precise work, comes the grand finale: the gold. Borrowed from another Japanese lacquer art called maki-e, the artisan paints a fine line of high-quality urushi along the repaired seams. While this final layer is still wet and tacky—a crucial window of perfect timing—they gently sprinkle superfine 22 or 24-karat gold powder over it using a delicate tool like a bamboo tube or soft brush. The gold adheres to the wet lacquer. The piece is then returned to the muro for the final curing. Once fully hardened, any excess gold powder is brushed off, and the golden lines are polished gently with silk or agate to reveal their brilliant shine. Understanding this entire process casts Kintsugi in a new light. The price of a professionally restored piece suddenly makes perfect sense. You’re not just paying for the gold; you’re paying for the artisan’s weeks or even months of time, their immense expertise, profound material knowledge, and meditative patience. It’s a labor of love, a tribute to the belief that what is broken deserves an extraordinary effort to be beautifully healed.

The Modern Glow-Up: Kintsugi in the 21st Century

It’s undeniable that Kintsugi has experienced a massive global surge in popularity over the past decade. It has moved beyond the realm of craft to become a powerful and widely recognized metaphor. You see it everywhere: on Instagram, in self-help books, therapy sessions, and corporate team-building exercises. “Be like a Kintsugi bowl!” the internet proclaims. “Embrace your flaws! Your scars make you beautiful!” The concept of ‘Kintsugi for the soul’ has become a popular analogy for psychological healing, resilience, and post-traumatic growth. And honestly, it’s not a bad metaphor at all—it’s actually quite powerful. The idea that our personal histories, traumas, and “cracks” don’t have to be hidden in shame is incredibly empowering. The notion that we can heal in ways that make us more interesting, complex, and beautiful than before is a message many of us need to hear. It offers a beautiful counter-narrative to the pressure to always appear perfect and composed. It validates the messy reality of being human. Yet, we need to be honest. Is this modern metaphor the same as the original Japanese concept? Or is it a classic case of cultural appropriation, where a rich, nuanced tradition is simplified into a catchy inspirational quote for a Western audience? The truth likely lies somewhere in between. On one hand, the metaphor’s power is undeniable and genuinely beneficial to many. It reflects the universal appeal of the philosophy behind Kintsugi and speaks to a fundamental human longing to find meaning in suffering and beauty in imperfection. On the other hand, there is a risk of oversimplification. When we just say, “Embrace your scars,” we run the risk of romanticizing trauma without recognizing the difficult, painful, and often unpleasant work involved in healing. Kintsugi isn’t a passive act of simply “being broken and beautiful.” It’s an active, deliberate, and highly skilled craft. It demands tremendous effort, resources, and care to transform those cracks into gold. It’s not about merely slapping glitter on your pain and moving on. The metaphor is most meaningful when it embraces the process—the patience, care, expert assistance, and investment of time and energy required to mend. The modern surge in interest has also sparked the rise of DIY Kintsugi kits. These are available online at a fraction of the cost of traditional repairs. Typically, they use modern materials like epoxy resin or polymer glue rather than urushi lacquer, and metallic mica powder or paint instead of real gold. They allow you to achieve the Kintsugi look in hours rather than months. So, is this “authentic” Kintsugi? From a purist standpoint, definitely not. They lack the traditional materials, the same skill level, and the deep ties to the history and philosophy of urushi craftsmanship. However, these kits have made the concept and aesthetic accessible to millions, encouraging people to reconsider discarding broken items. They introduce core ideas like mottainai and wabi-sabi, even if in simplified form. They offer a hands-on way to engage with the idea of repairing and beautifying the broken. Perhaps the best way to view it is as a gateway—an introduction to the aesthetic and philosophy. It plants a seed. But it’s important to remember that there is a far deeper, richer, and more demanding tradition behind the trend. The true art of Kintsugi is not just about the finished appearance; it’s about honoring the integrity of the process and the centuries of philosophy embedded in the lacquer itself.

Beyond the Bowl: The Kintsugi Mindset in Japan

Once you begin to seek it out, you start to notice the Kintsugi mindset—this philosophy of repairing, cherishing the old, and discovering beauty in imperfection—permeating many other aspects of Japanese culture. It extends far beyond pottery. It’s a thread woven into architecture, fashion, and even the general outlook on possessions. This worldview appears in unexpected places, quietly challenging the obsession with the new. Consider traditional Japanese architecture, for instance. Some of the oldest wooden structures in the world are in Japan, such as the temples of Horyu-ji in Nara, dating back to the 7th century. How have they endured earthquakes, fires, and over a thousand years? Through continuous, painstaking maintenance. The philosophy is not to wait until the entire structure is decayed and tear it down. Instead, carpenters and craftsmen have been carefully inspecting these buildings for centuries. When a single pillar begins to rot or a roof beam weakens, they don’t demolish the whole. They gently remove and replace that one part, seamlessly blending new wood with the ancient. Often, you can see the subtle variations in color and texture between the centuries-old timber and the newer sections. It’s a living structure, a patchwork of eras, constantly renewed and cared for. This is the Kintsugi mindset manifested on a grand scale. The building’s history of damage and restoration becomes part of its identity, a testament to its resilience. Then there’s textiles. Before Kintsugi gained international fame, there was boro. ‘Boro’ (ぼろ) means rags or tattered cloth. Historically, in rural Japan, fabrics like cotton were precious resources. People couldn’t simply discard a kimono or futon cover when it developed holes. Instead, they patched them. And when those patches wore through, they patched the patches. Over generations, these textiles transformed into intricate, multi-layered patchworks of indigo-dyed fabric. To reinforce worn areas, they used a running stitch called sashiko (刺し子). Originally practical, sashiko evolved into an art form, featuring beautiful geometric patterns embroidered in white thread on dark blue fabric. A boro garment tells the story of a family’s poverty, resourcefulness, and care. Like a Kintsugi bowl, every patch and stitch documents its history. What originated from necessity and the spirit of mottainai is now embraced by high fashion as a stunning example of wabi-sabi aesthetics. This respect for objects is also linked to the Shinto belief that items, especially those old and well-used, can acquire a spirit or soul, becoming tsukumogami (付喪神). A tool that has served its owner for a hundred years might awaken. This animistic perspective fosters a profound respect for belongings. You care for your tools, you clean and repair them, because they are not mere objects; they are partners in your work and life. Discarding them thoughtlessly is not only wasteful but disrespectful. This cultural foundation nurtured Kintsugi—a place where the old is honored, repair is a gesture of reverence, and an object’s story is its greatest value.

So, when you observe a bowl with golden cracks, you are witnessing more than a clever restoration technique. You see a physical expression of a worldview that starkly opposes modern fixation on flawlessness and disposability. Kintsugi is a quiet rebellion. It asserts that life, whether human or ceramic, is measured not by the absence of failure but by the ability to endure it. It proposes that breaking moments are not endings but chances for transformation, for rebirth into something uniquely beautiful. This philosophy values not an immaculate, untouched state but the rich, complex tapestry of a well-lived life, with all its chips, cracks, and golden repairs. It’s not about being broken. It’s about the grace and beauty of rebuilding oneself, creating something stronger, more resilient, and infinitely more intriguing than before. It’s a whole mindset, a way of perceiving the world that, once understood, feels less like an ancient, foreign idea and more like a profound and essential truth.