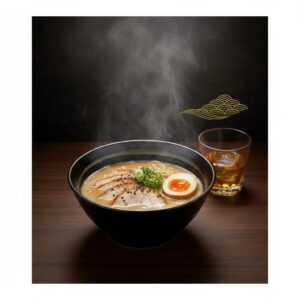

Yo, what’s the deal? You’ve seen it, I’ve seen it. Your feed is probably flooded with it. One minute, it’s a chaotic, steamy video of a dude in a sweaty headband, slinging noodles with lightning speed in a cramped, noisy shop. The next, it’s a perfectly curated, almost sterile photo of a single bowl of ramen, light hitting it just so, with a caption that says, “Michelin Star.” It’s a total vibe shift, and it’s kinda confusing, right? Ramen is supposed to be the people’s champ – the fast, cheap, soul-hugging food you crush after a long day or a night out. It’s the culinary equivalent of a warm hoodie. So when the Michelin Guide, the OG of fine dining gatekeepers, starts handing out stars to ramen joints, you gotta ask: what’s the tea? Is this just peak foodie hype, another case of slapping a premium price tag on something that was perfectly good, to begin with? Or is there something deeper going on? Is this a glow-up that actually makes sense? The truth is, that little star on that bowl of noodles isn’t just about soup and toppings. It’s a full-blown dissertation on modern Japanese culture, a deep dive into the national obsession with perfecting the everyday. It’s a story about how the humble can become holy through sheer, unfiltered dedication. Forget what you think you know about ramen from your instant noodle packets. We’re about to decode the matrix of a Michelin-starred bowl and figure out why it exists, what it means, and if it’s genuinely worth the pilgrimage. This ain’t your average food review; this is a cultural investigation. Let’s get it.

To truly understand this journey from the everyday to the extraordinary, it helps to explore the cultural foundations of Japan’s instant noodle obsession.

From Street Stall Slurp to Culinary Spotlight: Ramen’s Glow-Up

To truly understand why a Michelin star on a bowl of ramen is such a surprising idea, you need to rewind the story. Ramen’s beginnings are the complete opposite of luxury. It’s gritty, authentic, and closely connected to the daily life of the Japanese working class. This dish didn’t emerge from the pristine kitchens of imperial chefs; it was born out of necessity, hard work, and the need for something hot, quick, and satisfying.

A Brief History: More Than Just Instant Noodles

Ramen’s origins, as you might know, lie in China. It’s the Japanese reinterpretation of Chinese wheat noodle soups, or lamian. But its rise to cultural prominence in Japan is a post-World War II phenomenon. In a country rebuilding from devastation, affordable, calorie-rich food was vital. Wheat flour, imported in large quantities from the United States, became a dietary staple. Enter ramen. Mobile food stalls called yatai appeared everywhere, serving steaming bowls of noodle soup to factory workers, salarymen, and students. It was the fuel behind Japan’s economic boom.

Consider the contrast. Traditional Japanese haute cuisine, washoku, especially in its refined form, kaiseki, emphasizes subtlety, seasonality, and artistic presentation. It offers a quiet, reflective experience. Ramen was its rebellious, loud, younger counterpart. You didn’t enjoy ramen in hushed silence; you leaned over a counter, slurped noisily (a gesture of enjoyment and a practical way to cool hot noodles), and moved on with your day. It was democratic, accessible, and unapologetically rough. The broth was often a simple, straightforward flavor, the toppings were basic, and the whole meal cost just a few yen. It was the antithesis of the Michelin guide’s refined ethos.

The “Ramen Boom” and the Emergence of the Master Chef

So what changed? How did we go from a working-class lunch to a dish admired by French gourmands? The transformation began in the latter half of the 20th century, reaching a peak in the ’90s and 2000s during what Japan calls the “Ramen Boom.” This was when ramen became more than just food—it became a subculture, a passionate hobby, an obsession. The age of the ramen connoisseur had arrived.

Suddenly, ramen was no longer just ramen. There was Hakata tonkotsu, with its rich, creamy pork bone broth; Sapporo miso, with its robust, warming paste and toppings like corn and butter; and Tokyo shoyu, featuring a clear, savory soy-based soup. Regional styles became badges of pride. Magazines, TV shows, and eventually the internet were flooded with rankings, debates, and pilgrimages to seek the “best” bowl. Enthusiasts—known as “ramen freaks”—would line up for hours, treating chefs like rock stars.

This is where the figure of the ramen master, the taisho, evolved. He (and it was, and often still is, overwhelmingly a he) was no longer just a cook. He became an artist, a craftsman, a shokunin. The small ramen shop was his studio, the bowl his canvas. These chefs devoted fanatical attention to their craft, akin to that reserved for sushi masters or swordsmiths. They began to dissect and reinvent every element of the dish, pushing the boundaries of what a simple noodle soup could become. This relentless pursuit of perfection caught the eye of Michelin inspectors. They weren’t just evaluating a dish; they were witnessing a craft at its peak. The transformation was complete. Ramen had claimed its place in the world of global gastronomy.

Deconstructing the Michelin Bowl: It’s All About the Kodawari

Alright, so we’ve set the scene. Ramen transformed from humble street food into a national obsession. But what truly distinguishes a ¥3,000 Michelin-starred bowl from the ¥900 bowl you grab at your local train station? The answer lies in one profoundly Japanese term: kodawari (こだわり). It defies a perfect English translation but roughly means an obsessive, uncompromising, fanatical attention to detail. It’s a relentless pursuit of perfection, often at a microscopic level that most wouldn’t even notice. In a Michelin-starred ramen, every single element embodies the chef’s kodawari. Let’s dissect it, piece by piece. This is where things get fascinating.

The Broth (スープ – Soup) – The Heart and Soul of the Bowl

The broth is unquestionably the soul of any ramen. In a high-end bowl, it’s far more than just liquid; it’s a complex, multi-layered elixir that could have taken days, or even years, of trial and error to perfect. The complexity is staggering.

The Craft of Double (and Triple) Soups

A typical neighborhood ramen spot might create a solid broth from one primary ingredient, such as pork bones (tonkotsu) or chicken carcasses (torigara). It’s tasty, straightforward, and comforting. Michelin-level chefs, however, play at a whole other level. They master the “W Soup” or “Double Soup” technique, where two entirely distinct broths are prepared and then blended together. Sometimes, it’s even triple or quadruple-layered.

One broth may be animal-based—a rich, collagen-packed stock made from several chicken breeds like Jidori or Shamo, pork bones, and trotters, simmered for 8-12 hours at a precise, non-boiling temperature to capture pure flavor without cloudiness. The second broth is usually gyokai, or seafood-based—not just fish stock but a delicate dashi made from a carefully curated selection: premium Rishiri kombu from Hokkaido, aged katsuobushi from a specific Kagoshima producer, dried niboshi (sardines), or ago (flying fish). Each ingredient is steeped at exact temperatures to extract unique umami without bitterness. These two (or more) broths are then precisely blended just before serving, crafting a final soup that marries the richness of the land with the profound umami of the sea. The resulting flavor profile is breathtaking. It unfolds in waves—first savory chicken, then deep pork undertones, finishing with a refined briny note from the dashi. It’s a symphony.

Sourcing Matters

Kodawari extends to sourcing each ingredient individually. These chefs don’t just order “chicken.” They select specific heritage breeds from particular farms. They don’t use ordinary water; sometimes, it’s specially filtered or mineral-balanced to optimize flavor extraction. The salt might combine Mongolian rock salt and Okinawan sea salt. They build their broth much like a perfumer layering a fragrance—top, middle, and base notes. This level of ingredient obsession rivals any three-star restaurant in Paris.

The Tare (タレ) – The Secret Weapon

If broth is the soul, the tare is the personality. The tare is the concentrated seasoning poured into the bottom of the empty bowl before the broth. It officially designates the ramen as shio (salt), shoyu (soy sauce), or miso. To outsiders, it may seem minor, but to a ramen master, the tare is everything: their most guarded secret, signature, and artistic DNA.

A standard shoyu tare might be a simple mix of soy sauce, mirin, and sake. A Michelin-level shoyu tare is an entirely different creature. The chef might blend five or six artisanal soy sauces, some aged for years in cedar barrels. This mixture is gently heated with kombu, shiitake mushrooms, and other aromatics to boost umami. Some chefs, like the late Yuki Onishi of Tsuta (the world’s first Michelin-starred ramen shop), famously incorporated black truffle oil and red wine, marrying Japanese tradition with European haute cuisine. A shio tare may use a complex brine combining multiple sea salts, scallops, and dried shrimp. This isn’t mere seasoning; it’s a flavor bomb crafted with scientific precision. The tare defines the broth’s sharp, distinctive character and incredible depth.

The Noodles (麺 – Men) – The Perfect Bite

Ramen isn’t ramen without noodles, and in elevated ramen, the noodle is an object of intense focus and obsession. Commercial noodles aren’t an option; nearly every high-end shop makes their noodles fresh daily.

The In-House Edge

Making noodles in-house gives chefs total control over texture, flavor, and shape. It’s a labor-intensive but essential process for perfection seekers. They adjust recipes daily based on humidity and room temperature to ensure absolute consistency. It’s the difference between ready-to-wear and bespoke tailoring.

Flour Blends and Hydration Ratios

Here’s where it gets technical. Ramen masters are essentially noodle engineers. They don’t just use “flour”; they develop custom blends of different wheats, each with distinct protein levels, to achieve the perfect balance of firmness and elasticity. Some, like the chefs at Nakiryu (another Michelin-starred Tokyo spot), add whole-wheat flour or other grains for a richer, nuttier flavor that stands up to their soups. They obsess over hydration—the water-to-flour ratio—which determines texture: lower hydration yields firm, snappy noodles ideal for rich tonkotsu broths, while higher hydration produces softer, wavier noodles better suited for lighter shoyu soups. They also meticulously control the amount of kansui, the alkaline solution that gives ramen noodles their yellow color and springy koshi texture. Shape matters too—thin and straight, thick and wavy, flat and wide—each designed to complement a specific broth precisely. It’s a deep, detailed science dedicated to crafting the perfect soup vehicle.

The Toppings (具 – Gu) – Beyond Mere Garnish

Finally, toppings. In an everyday bowl, they’re often an afterthought. In a Michelin bowl, each topping is a carefully prepared component worthy of standing alone as its own dish. They complement rather than merely decorate.

The Chashu Revolution

The classic topping is chashu, braised pork. Traditionally, it’s rolled pork belly simmered in a sweet soy liquid. The new generation of ramen chefs has thoroughly reinvented it. Inspired by French and modern gastronomy, many use sous-vide cooking at low, precise temperatures for hours, yielding impossibly tender, juicy meat. They experiment with cuts—pork shoulder, loin, or even Iberico pork. Some shops, like Konjiki Hototogisu, serve two types of chashu in one bowl to provide contrasting textures and flavors. Other proteins, like pink-cooked duck breast or tender chicken breast, receive similar reverence. This isn’t boiled meat; it’s pork charcuterie.

The Elevated Egg (Ajitama)

The marinated soft-boiled egg, or ajitama, is a benchmark of ramen quality. A perfect ajitama is a masterpiece: firm whites without rubberiness, and a yolk that’s molten, jammy, and luscious when bitten. Achieving this requires exact boiling times followed by multi-day marination in a custom brine often derived from the shop’s chashu liquid. This simple item reveals a kitchen’s discipline and fine attention to detail.

The “WTF” Ingredients

This is where creativity shines. The toppings showcase chefs’ inventiveness and global influences. Tsuta became world-renowned for incorporating black truffle sauce—a daring choice that surprised ramen purists but ultimately elevated the entire bowl with its luxurious, earthy aroma. You might find porcini mushroom duxelles, clam and mussel purees, drizzles of premium olive oil, or asparagus spears. Even traditional toppings get elevated: menma (bamboo shoots) slow-braised in special broth for days, and green onions (negi) sourced from a select farm near Kyoto known for their sweetness. Every item in the bowl serves a purpose, has a pedigree, and tells a story. It’s a fully curated ecosystem of flavor.

The Vibe Check: Why the Michelin Ramen Experience Feels… Different

So, you’ve made up your mind to go. You’ve either conquered the online reservation system or committed to standing in line. Once inside, the experience itself can be as surprising as the thought of a $20 bowl of noodles. If you anticipate the loud, chaotic, “irasshaimase!”-shouting atmosphere typical of a classic ramen-ya, you might be taken aback. The ambiance at a Michelin-level establishment is an entirely different experience, deeply rooted in the same principles of focus and respect that shape the food.

Silence of the Slurps: The Zen of the Counter

Most of these renowned ramen shops are quite small—often only 8 to 12 seats, usually arranged along a single wooden counter. This isn’t the place for extended, leisurely chats with friends. The layout is deliberate. It creates an intimate theater where the chef performs and the diner is the audience. The attention is fully centered on the bowl before you.

The atmosphere tends to be quiet, almost reverent. You’ll hear the clinking of bowls, the gentle swish of the noodle strainer, the soft pour of broth, and naturally, the sound of slurping. The near silence isn’t intended to be intimidating or stuffy. It’s a form of respect—respect for the chef’s intense focus, respect for fellow diners on a culinary pilgrimage, and above all, respect for the food itself. The chef has poured their entire being into crafting this perfect bowl, which has a peak flavor that lasts only a few minutes before the noodles soften and the broth cools. You’re expected to give it your undivided attention. You’re not simply eating; you’re participating in a moment of focused appreciation. It’s mindfulness, expressed through noodles. You eat, you savor, and then you make room for the next pilgrim. It’s a high-turnover, high-focus environment.

The Ticketing Machine and the Line: A System of Order

Before sitting down, you’ll likely encounter two quintessential Japanese systems designed for maximum efficiency and fairness: the well-known line and the ticket machine. For many non-Japanese visitors, the shokkenki (食券機), or meal ticket vending machine, can be confusing. Positioned usually near the entrance, it features buttons for each menu item. You insert your cash, make your choice, and receive a small ticket to give to the chef or staff.

From an outsider’s perspective, this might feel impersonal. Where’s the warm welcome, the menu explanation, the personal order-taking? But within a high-focus ramen shop, it’s pure genius. It streamlines the whole process. The chef—often the owner and sole operator—never handles money, which is considered unhygienic in the kitchen. They don’t have to take orders or calculate bills. Their mind stays 100% focused on cooking. This eliminates distractions and maximizes efficiency, ensuring every bowl is crafted with unwavering attention.

The line, or its absence if you secure a reservation, is another part of the ritual. For a popular spot, waiting an hour or more is normal. This isn’t just waiting; it’s a testament to the shop’s reputation and a filter for patrons. It guarantees that everyone who gets a seat truly values the food. There’s an unspoken etiquette in the line: no saving spots, no complaining, just patiently waiting your turn. The system is the system. It’s a deeply rooted cultural practice that emphasizes order and fairness. Both the machine and the line embody the Japanese passion for elegant, efficient systems that allow the artisan to focus on what matters most: the craft.

So, Is It Worth It? The Michelin Star vs. Your Local Spot

This is the crux of the matter—the essential question. After dissecting the broth, praising the noodles, and assessing the overall vibe, you stand there with 3,000 yen in your hand, facing a line of people and wondering, “Is this really worth it? Or should I just head to that reliable spot around the corner for a third of the price?” The frustratingly honest answer is: it entirely depends on what you’re seeking. It’s not a clear yes or no.

It’s Not About “Better,” It’s About “Different”

The biggest mistake people make is trying to evaluate a Michelin-starred bowl by the same criteria as a traditional, hearty Hakata-style tonkotsu ramen. That’s like comparing a Formula 1 car to a rugged off-road Jeep. Both are excellent vehicles but built for completely different purposes and terrains. A Michelin-starred ramen isn’t aiming to be the most comforting, gut-busting, soul-soothing bowl you crave at 2 AM. It’s culinary art meant to be contemplated, analyzed, and admired. It’s about balance, complexity, and subtle flavor nuances that you might overlook if you’re just trying to fill your stomach. Meanwhile, the rich, fatty, unapologetically bold tonkotsu from a Fukuoka street stall is perfect in its own right, serving a different god: the god of pure, unfiltered satisfaction. One is an intellectual experience; the other a primal one. Declaring one “better” than the other misses the point entirely. They exist in separate worlds, and both are valid and beautiful.

The Price Tag: You’re Paying for the R&D

Let’s discuss the cost. Why is it so high? When you pay that premium, you’re not just paying for the ingredients in that one bowl. You’re paying for the chef’s entire journey—the hundreds of broth failures, the trip to a remote soy sauce brewery to find the perfect tare blend, the costly noodle-making machine, and the years spent mastering it. You’re paying for R&D, sleepless nights, and unrelenting obsession. That bowl of ramen embodies the physical manifestation of a person’s lifelong work and fanatical pursuit of an ideal. Viewed this way, the price starts to make sense. You’re not buying a mere meal; you’re commissioning a piece of performance art. You’re supporting a level of craftsmanship that’s increasingly rare in a mass-produced world.

The Takeaway: A Window into Modern Japanese Perfectionism

Ultimately, experiencing a Michelin-starred ramen isn’t necessarily about having the most delicious meal ever (though it might be), but about what it symbolizes. It’s a flawless, edible microcosm of a key pillar of modern Japanese culture: elevating the mundane to the level of art. It reflects the belief that no task is too humble, no craft too simple, to become a path to mastery. This is shokunin damashii—the artisan’s spirit.

It’s the same spirit you see in the bartender carving a perfect ice sphere for your whiskey, the train conductor bowing to departing cars, or the depachika worker wrapping a simple pastry like a priceless jewel. It’s a deep cultural conviction that dedication, focus, and relentless pursuit of perfection are virtues in themselves, no matter the task. For these chefs, the Michelin star isn’t the goal; it’s a byproduct—external recognition of an internal quest already underway. So, when you sit at that quiet counter and lift that first spoonful of impossibly complex broth to your lips, you’re not just tasting soup. You’re tasting obsession. You’re tasting discipline. You’re tasting the very modern soul of Japan, distilled into one perfect, utterly unforgettable bowl.