Yo, what’s up world! Li Wei here, coming at you with a journey that’s less about a destination and more about a vibe. A whole mood. We’re diving headfirst into the world of Tadao Ando, the legendary, self-taught architect from Osaka who basically taught concrete how to feel. Forget what you think you know about architecture being just buildings. Ando’s work is an experience, a conversation between you, the structure, and the world around it. It’s a pilgrimage for the soul, and honestly, it’s a trip that will rewire how you see light, shadow, and the very space you occupy. Think of it as a quest to find the Zen in the geometry, the poetry in the pavement. We’re talking about spaces that are so intensely minimal yet so deeply profound, they hit you right in the feels. It’s about tracking down these masterpieces scattered across Japan, from bustling cities to serene art islands, and letting them speak to you. This isn’t just about snapping pics for the ‘gram; it’s about standing in a space and feeling the universe shift, just a little. It’s about understanding how a wall of smooth, grey concrete can hold more emotion than a thousand words. So, grab your comfiest walking shoes and an open mind, because we’re about to embark on an architectural pilgrimage that’s low-key one of the most spiritual journeys you can take in modern Japan. It’s time to explore the soul of concrete.

To further explore the profound impact of concrete in modern Japanese design, consider how its raw beauty is also masterfully expressed in the brutalist architecture of Japan’s Shinkansen.

The Ando Philosophy: Concrete as Canvas, Light as Brush

Before you even enter one of his designs, you need to understand the philosophy behind it. This philosophy serves as the source code for everything he creates. Ando’s work goes beyond mere aesthetics; it embodies a profound, meditative practice realized in physical form. He is a master at using the simplest materials—mainly concrete, steel, glass, and wood—to craft spaces that are complex, emotional, and deeply interwoven with nature. It’s a trinity of elements: the solid, impenetrable strength of concrete; the fleeting, ever-changing play of light; and the raw, untamed presence of nature. He doesn’t merely build on the land; he engages in a dialogue with it. Sometimes he carves into the earth, and other times he constructs bold structures that frame the sky. This tension and balance is what makes his architecture so captivating. It’s not about conventional comfort. He famously said he wants people to engage their five senses—to feel the cold of winter and the heat of summer, to notice the rain and the wind. His buildings compel you to be present and mindful. They aren’t passive backdrops to life; they actively shape our experience of the world.

The Soul of Bare Concrete (コンクリート打ちっ放し)

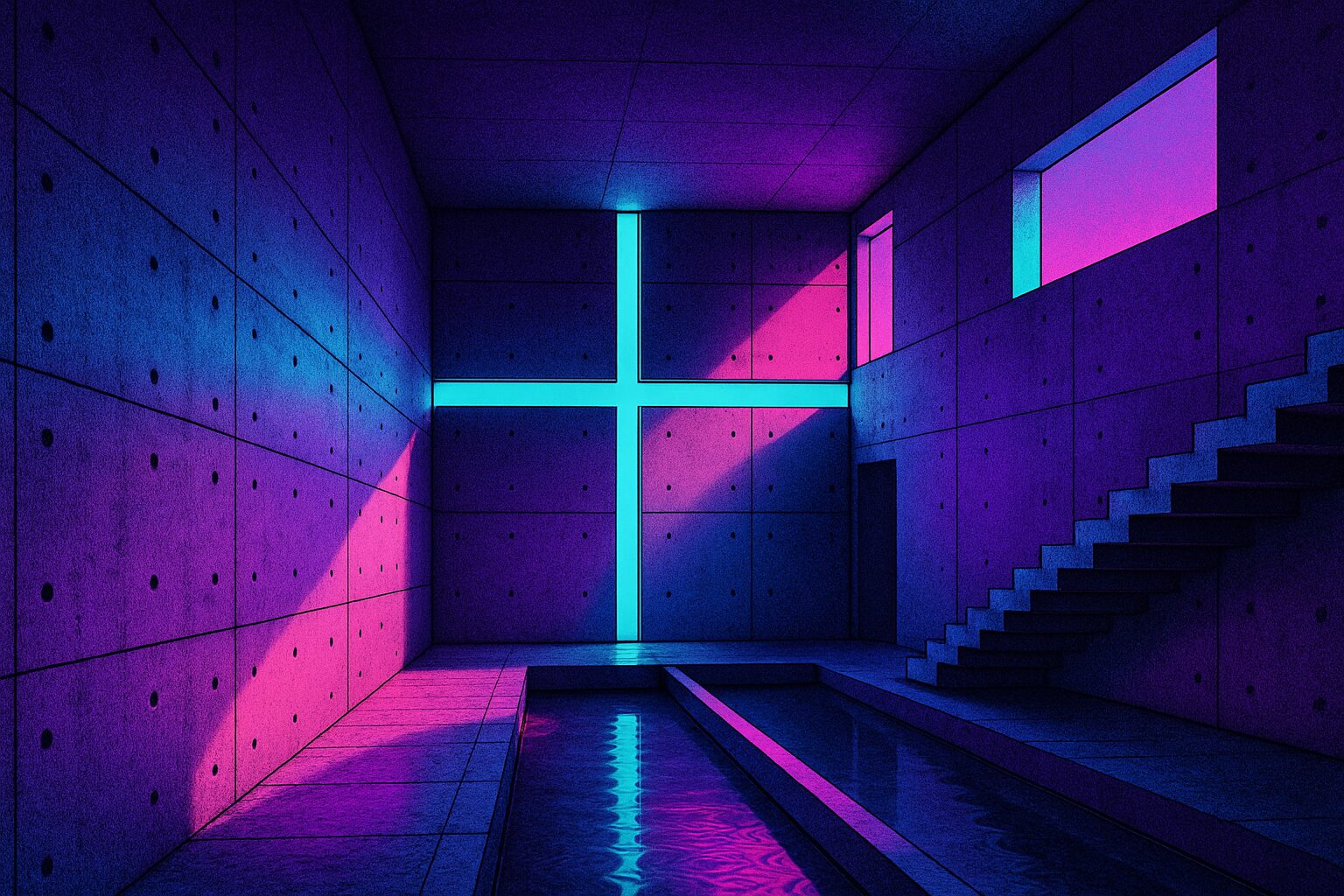

Let’s be clear: Ando’s concrete is no ordinary sidewalk slab. This is uchi-hanashi, or exposed concrete, elevated to an art form. It’s flawless, silky smooth, and possesses a luminous quality that seems to both absorb and reflect light in an ethereal way. When you run your hand along one of his walls, it feels surprisingly warm and organic. The secret is in the absolute precision of its creation. The wooden formwork, or konwakupata, is crafted with the skill of a master carpenter, guaranteeing every surface is perfect. The concrete mix itself is a closely guarded secret, producing a dense, uniform grey that ages gracefully. And those iconic, evenly spaced holes on his walls? They are remnants of the bolts that held the formwork, but Ando transforms this functional aspect into a deliberate, rhythmic pattern—a signature architectural punctuation. This obsession with perfection is deeply rooted in the Japanese spirit of monozukuri—the art and science of craftsmanship. Paradoxically, this flawless, man-made material highlights the imperfect, constantly changing beauty of the natural world it frames. It acts as a canvas that makes shifting light, rustling leaves, or falling rain the main spectacle. In this way, it embodies the aesthetic of wabi-sabi—finding beauty in simplicity, austerity, and the subtle marks of time.

The Choreography of Light and Shadow

If concrete is Ando’s canvas, light is his brush. He is a virtuoso of natural light, a master choreographer of sunbeams and shadows. In his buildings, light is never just illumination; it becomes a tangible medium that carves, defines, and animates space. He employs razor-thin slits, vast glass walls, and precisely positioned openings to direct light—making it cascade along a wall, pool in a corner, or cut through darkness with dramatic effect. The experience of an Ando building changes entirely with the time of day and season. A space that feels somber and contemplative at dawn can become lively and joyful at noon. The shadows shift with life of their own, stretching and contracting on concrete walls, creating a slow, silent dance marking the passage of time. This vitality makes his architecture breathe with the rhythm of the day. The most iconic example is the Church of the Light, where a cross is not formed by an object but by a void—a cruciform cut in the concrete wall allowing pure light to flood the dark interior. It is an act of dematerialization, where faith and spirituality are embodied by absence, the pure, unfiltered presence of light itself. This represents Ando at his most profound, transforming a simple building material into a channel for a powerful, almost mystical experience.

Weaving Nature into the Urban Fabric

For Ando, architecture serves as a bridge between humanity and nature, even amidst dense urban settings. He believes that a connection to nature—whether a glimpse of the sky, the sound of water, or the feel of wind—is crucial for human well-being. He skillfully integrates natural elements into his designs, creating a compelling contrast and beautiful harmony between the man-made and the organic. This isn’t about placing sprawling gardens next to buildings; it’s about embedding nature at the very core of the structure. He often arranges buildings around a central courtyard open to the sky, compelling residents to step outside to move between rooms, ensuring daily contact with the elements. Water is another frequent element—still, reflective pools mirror the sky and surrounding architecture, evoking tranquility and infinity. The sound of water, whether a gentle cascade or a lapping surface, adds an auditory dimension to the sensory experience. At Awaji Yumebutai, a vast complex built on a site ravaged by earthquake, he created a hundred terraced gardens filled with flowers—a poignant symbol of regeneration and hope. He demonstrates that even with the hardest materials, spaces can feel soft, alive, and deeply anchored to the earth. This ongoing dialogue between the raw power of concrete and the gentle persistence of nature is at the heart of his architectural poetry.

The Sacred Island: Naoshima, An Art Utopia

Your Ando pilgrimage isn’t complete without a visit to Naoshima. This small island in the Seto Inland Sea is a genuine paradise for art and architecture enthusiasts. The entire island has been transformed into a living museum, with Tadao Ando’s vision at its core. The journey there adds to the magic—you leave behind the mainland’s hustle by taking a ferry from Uno Port in Okayama Prefecture. As the coastline fades and the island approaches, a sense of relaxation washes over you. You’re entering a different reality, one that moves to “island time” and revolves around art. The air feels fresher, life slows down, and the sea’s landscape, dotted with tiny islands, is breathtaking. This is the ideal mindset to embrace before experiencing Ando’s work, which is designed to harmonize perfectly with the stunning natural environment. On Naoshima, his architecture doesn’t just house art; it becomes part of the artwork itself, creating a seamless experience that blurs the boundaries between nature, structure, and human creativity. You’ll need at least two full days to scratch the surface here, and the best way to explore is by renting an electric-assist bicycle, allowing you to effortlessly climb the island’s hills and uncover its hidden gems at your own pace.

Descending into the Earth: Chichu Art Museum

Prepare to be amazed. The Chichu Art Museum is Ando’s masterpiece, a building that redefines what a museum can be. Its name, “Chichu,” means “in the earth,” and true to this, most of the museum is built underground to preserve the island’s natural coastline. From outside, it is barely visible—only geometric openings in the green hillside—squares, rectangles, and triangles open to the sky. The journey begins at the ticket center, a sleek Ando-designed building, from which you walk along a lovely path adorned with flowers and ponds inspired by Monet’s garden at Giverny, subtly hinting at what awaits inside. Inside the museum, you navigate a labyrinth of cool, silent concrete corridors. Ando’s genius lies in how he manipulates natural light within these subterranean spaces. Despite being underground, the galleries are illuminated by soft, diffused light from geometric skylights, and the quality of light shifts constantly with the weather and time of day. The museum is dedicated to just three artists: Claude Monet, Walter De Maria, and James Turrell. The architecture was tailor-made for these artworks, creating a perfect, permanent union of art and space. The Monet room, showcasing five “Water Lilies” paintings, is breathtaking. The entire room—from the white walls to the floor of 200,000 marble cubes—is lit solely by natural light, allowing you to appreciate the paintings as Monet intended. The Walter De Maria room is temple-like, featuring a massive granite sphere on a grand staircase, an awe-inspiring installation that feels both ancient and futuristic. The James Turrell works challenge your perception of light, space, and reality. The Chichu Art Museum demands your full attention; it’s a slow, contemplative experience that will linger with you long after you leave.

Benesse House Museum: Where Art and Nature Reside

If Chichu is an underground temple, the Benesse House Museum is a panoramic gallery open to sea and sky. This unique facility combines a museum and hotel under the concept of “coexistence of nature, art, and architecture.” Staying here offers the ultimate immersive experience, letting you live with art around the clock. Ando’s building perches on a hill overlooking the shimmering Seto Inland Sea, characterized by long ramps, expansive picture windows, and grand open spaces that blend interior and breathtaking coastal scenery seamlessly. The concrete walls frame the ever-changing sea views, turning the landscape into a living artwork. The collection includes renowned contemporary artists from Japan and abroad, and the art extends beyond the museum walls onto the surrounding grounds and coastline. You can stroll among outdoor sculptures by artists such as Yayoi Kusama (her iconic “Yellow Pumpkin” on a pier is a beloved island symbol), Niki de Saint Phalle, and Karel Appel. Waking up here to the sunrise over the sea from your room and wandering the galleries before day-trippers arrive is an unmatched experience. Even if you don’t stay overnight, visiting the museum is essential. The building’s striking geometry and its ongoing dialogue with nature make it a quintessential Ando experience. Pro tip: the on-site restaurants serve exceptional food accompanied by incredible views. Booking a room requires advance planning—sometimes up to a year—but it is well worth it for dedicated art pilgrims.

The Ando Museum: A Dialogue Between Old and New

To grasp Ando’s role within the long tradition of Japanese aesthetics, visit the Ando Museum in Honmura. This district is known for the Art House Project, where artists transform empty traditional houses into permanent art installations. Ando’s contribution is a masterful architectural dialogue. He took a 100-year-old traditional wooden house, a minka, and inserted his signature concrete world within it, carefully preserving the original exterior and character. From the outside, it looks like any other charming old Japanese home with dark wood and a tiled roof. But inside, you enter a completely different realm: a smooth, light-filled concrete structure built within the old wooden frame. The contrast is striking—the dark, rough-hewn wooden beams stand in sharp contrast to the clean, geometric lines of the new concrete interior. A conical concrete volume, dramatically illuminated by a skylight above, forms the central chamber. Here, you can view drawings, sketches, and models of his work on Naoshima and beyond. Though small, the museum is profoundly impactful. It embodies a physical conversation between past and present, tradition and modernity, wood and concrete, darkness and light. It encapsulates Ando’s philosophy: deep respect for history and context, combined with a bold, contemporary vision. It’s the perfect place to reflect on his journey and the profound influence he has had on this small, magical island.

The Urban Sanctuaries: Ando in Kansai

While Naoshima may be considered the spiritual core of the Ando pilgrimage, his home region of Kansai—encompassing Osaka, Kobe, and Kyoto—is where some of his earliest and most iconic urban works are found. These buildings reveal a different facet of Ando, one that contends with the chaos and limitations of city life. He creates spaces of profound serenity and spiritual depth amid the noise and concrete expanse. These are more than just buildings; they are sanctuaries, strongholds of tranquility that turn inward, crafting their own private realms of light and shadow. Exploring his work in Kansai is crucial to understanding how his architectural language evolved and how he applies his principles across varied contexts, from a sacred church to a vast public museum. This is where the boxer-turned-architect refined his craft and built his legendary reputation.

A Cross of Pure Light: The Church of the Light, Ibaraki, Osaka

This is the pinnacle. The holy grail for many Ando enthusiasts. The Church of the Light, situated in the quiet residential suburb of Ibaraki, Osaka, is among the most renowned and spiritually potent architectural works of the 20th century. From the exterior, it appears deceptively simple—a plain, monolithic concrete box. There’s no steeple or grand entrance. It’s understated, almost invisible. Yet, this modest exterior hides an interior of immense power. You enter through a deliberately angled wall that funnels you into a dark, narrow passage before emerging into the main chapel. Then it reveals itself. The entire wall behind the altar is a solid concrete slab, but a vertical and a horizontal slit are precisely cut through it, floor to ceiling and wall to wall, forming a stunning cross of pure, unfiltered light. The slit contains no glass; it is open to the elements, letting light, wind, and rain enter the sacred space. The effect is overwhelming. In the austere darkness of the chapel, the light is so intense and palpable it feels almost like a tangible, divine presence. The rest of the interior is stripped to essentials: concrete walls, simple wooden floors and pews. Nothing distracts from the raw, elemental power of the space and the light. It is a profound meditation on duality—darkness and light, solid and void, material and spiritual. An important piece of advice for any pilgrim: this is an active church, not a tourist museum. Visits are strictly regulated, and you must make a reservation in advance via their official website. Check the schedule carefully, respect the rules, and prepare for a deeply moving experience.

A Spiral of Culture: Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art, Kobe

If the Church of the Light is an intimate, inward-focused sanctuary, the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art in Kobe stands as its opposite: a grand, public, outward-facing monument. Located on the redeveloped waterfront, the museum is a massive symbol of strength and optimism, constructed as a testament to Kobe’s reconstruction and recovery after the devastating Great Hanshin Earthquake of 1995. This backdrop is essential to grasping the building’s impact. It is a formidable structure, a colossal composition of concrete and glass. Its most striking element is a dramatic circular staircase at its core—a spiral connecting different levels and providing dizzying views. Ando manipulates levels and sightlines throughout the building, creating a complex and engaging journey for visitors. Glass-enclosed corridors extend toward the sea, rooftop terraces offer panoramic vistas, and galleries vary in size and lighting. Unlike his more enclosed projects, this museum actively engages with its surroundings—the port, mountains, and sky. It feels open and lively, a hub of culture rather than a quiet contemplation space. Don’t miss the outdoor sculpture deck and the iconic giant green frog sculpture by Florentijn Hofman on the rooftop. Easily accessible from central Kobe, the museum powerfully exemplifies both Ando’s versatility as a designer and the resilience of the human spirit in the face of tragedy.

A Memorial in Bloom: Awaji Yumebutai, Awaji Island

For a truly epic, full-day Ando experience, head to Awaji Island, linked to Kobe by the world’s longest suspension bridge. Here lies Awaji Yumebutai, an expansive complex that serves as a conference center, hotel, memorial, and landscape art all in one. The story behind it is deeply moving. The site was originally a hillside that was literally stripped away, its earth used as landfill in the construction of Kansai International Airport in Osaka Bay. Ando was commissioned to restore this scarred landscape. During construction, the Great Hanshin Earthquake struck, with its epicenter near Awaji Island. The project then took on new, deeper meaning: it became a memorial for the earthquake victims and a symbol of renewal. The result is one of Ando’s most ambitious and complex undertakings. It’s a labyrinth of concrete structures intertwined with water features and expansive gardens. The undisputed highlight is the Hyakudanen, or “one hundred stepped gardens”—a breathtaking grid of 100 small, square flowerbeds arranged in tiers along the hillside, a tribute to those who lost their lives. Exploring Yumebutai is a journey of discovery. You wander through concrete plazas, along tranquil water spaces, past a garden made entirely of seashells, and ascend countless stairways. It can be overwhelming, yet profoundly rewarding. It’s a place celebrating the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. For the best experience, visit in spring or autumn when the Hyakudanen flowers are in full bloom. Wear comfortable shoes, as there will be much walking, and allow yourself to get lost in its magnificent, meditative landscape.

The Pilgrim’s Guide: Practicalities and Etiquette

Embarking on an Ando pilgrimage requires some planning to fully appreciate it. This isn’t a typical sightseeing trip where you can simply show up. Many of his significant works are located off the beaten path or have specific visiting rules. However, with a bit of preparation, you can enjoy a smooth and deeply fulfilling journey into his architectural universe. Consider it like preparing for a multi-day hike; you need the right equipment, a reliable map, and the proper mindset. The key is to slow down and let the spaces gradually unveil themselves. Avoid rushing from one photo opportunity to another. The true essence of Ando’s work lies in the quiet moments of contemplation.

Planning Your Ando Itinerary

A sensible and efficient way to organize your trip is to begin in the Kansai region and then head to Naoshima. Fly into Kansai International Airport (KIX), which serves Osaka, Kobe, and Kyoto. You can base yourself in Osaka or Kobe and take day trips. Dedicate a full day to the Church of the Light (make sure to book well in advance!) and other smaller Ando sites in Osaka. Spend another day exploring Kobe’s Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art, and if you have the time and energy, visit Awaji Yumebutai. After experiencing his urban projects, take the Shinkansen (bullet train) from Shin-Osaka or Shin-Kobe to Okayama. From Okayama Station, it’s a short local train ride to Uno Port, where you’ll catch a ferry to Naoshima. Plan to spend at least two full days and one night on Naoshima; three days is even better if you want to explore everything without rushing. A Japan Rail Pass can be cost-effective if you’re traveling from Tokyo or other areas of Japan. On Naoshima, renting an electric bicycle is the best way to get around and enjoy the scenery. Be sure to book your accommodation, especially on Naoshima, months ahead, as places fill quickly, particularly during peak seasons (spring and autumn) and the Setouchi Triennale art festival.

The Art of Observation

To truly appreciate an Ando building, engage all your senses. This architecture demands mindfulness. When entering one of his spaces, take a moment to stand still and breathe. Notice the air’s temperature. Listen to the silence or the echo of your footsteps on the concrete floor. Run your hand along a wall to feel its texture. Observe how light enters and shifts throughout the day. Find a quiet corner and sit for ten or fifteen minutes. Watch the shadows dance. Notice the details—the precision of the joints, the meeting of glass and concrete, the framing of a single tree or a glimpse of sky. Many of Ando’s most compelling works, like the Chichu Art Museum and the Church of the Light, prohibit photography inside. Don’t see this as a limitation; see it as a gift. It frees you from the pressure to capture images, allowing you to simply be in the moment. Instead of a camera, bring a small sketchbook or journal. Jot down your impressions, a quick sketch of a light pattern, or a few words capturing the atmosphere. The memories you create through direct, unfiltered experience will be far more vivid and lasting than any photograph.

What to Pack and Expect

First and foremost, comfortable shoes are essential. You’ll do a lot of walking, climbing stairs, and navigating expansive complexes. Bring layered clothing, as many of Ando’s spaces can feel cool inside due to the concrete, and you’ll be moving frequently between indoor and outdoor environments. Japan remains a mostly cash-based society in many smaller establishments, so it’s wise to carry some yen, especially for local buses, bike rentals, or small island cafes. A portable battery charger for your phone is invaluable, especially when using it for navigation throughout the day. Above all, bring an open mind and a patient heart. Be ready for buildings that challenge your comfort, require more walking, and confront you with the elements. This is not passive architecture; it invites your active participation. And remember to always be respectful. These are not simply tourist sites; they are active churches, art museums demanding quiet, and public spaces cherished by local communities. Approaching your pilgrimage with reverence and curiosity opens you to the profound and transformative power of Tadao Ando’s world.

Beyond the Concrete: Ando’s Enduring Legacy

Completing a pilgrimage to Tadao Ando’s masterpieces is more than merely checking off a list of buildings. It’s a journey that profoundly reshapes your perception. You emerge with heightened awareness of the world around you and a renewed appreciation for the quiet poetry in everyday spaces. You begin to notice how light falls in your own home, the texture of a city sidewalk, and the elegance of a simple, clean line. Ando’s architecture introduces a new language—a way of seeing and feeling that transcends culture and borders. From my perspective, as someone deeply interested in East Asian aesthetics, I recognize a strong connection between Ando’s work and ancient philosophies. His use of empty space, the void, is as vital as the solid material, reflecting the principles of Daoist thought and traditional Chinese landscape painting, where the unpainted space on the scroll is rich with meaning and energy, or qi. His ability to evoke profound tranquility through extreme simplicity feels like a contemporary interpretation of Zen principles—a path to enlightenment not through ancient texts or rituals, but through the direct, unmediated experience of space, light, and nature. He has crafted a new kind of sacred space for our secular, modern age. Though the pilgrimage concludes, the lesson remains with you. It invites you to discover your own moments of clarity, your own sanctuaries of silence amid our noisy, chaotic world. In that, you encounter the true art of concrete.