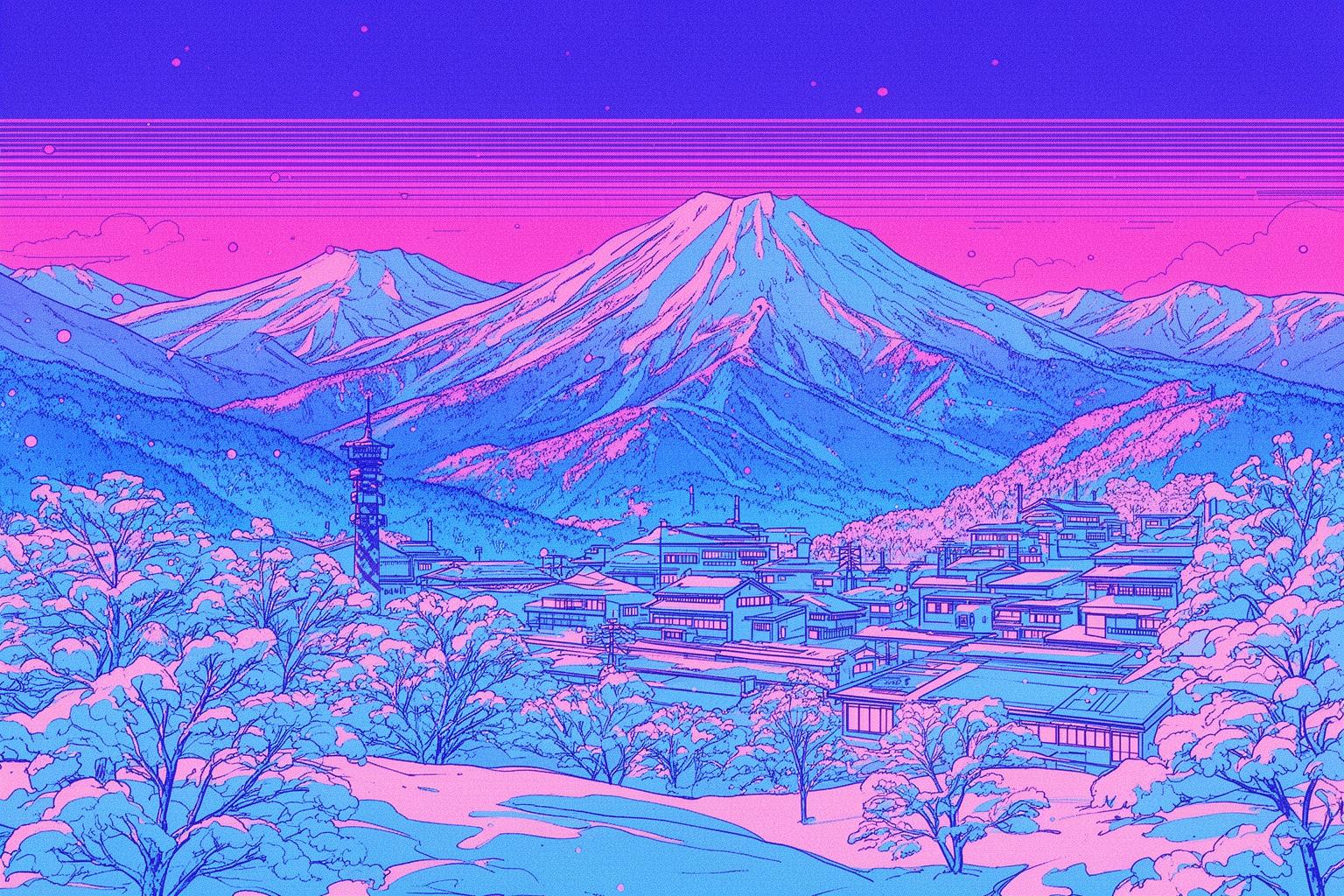

What’s up, fellow travelers? Li Wei here, coming at you from a place that’s less of a destination and more of a whole mood. Imagine this: you’re on a bullet train, zipping away from the neon chaos of Tokyo. Concrete and steel blur past the window, a familiar urban rhythm. Then, you enter a tunnel. Not just any tunnel, but a long, impossibly deep passage that bores straight through the spine of Japan’s central mountains. For minutes, you’re suspended in darkness, the only sound the hum of the train. And when you burst out on the other side, it’s like you’ve been teleported to another planet. Everything is white. A profound, silent, all-encompassing white that blankets the world. This isn’t a dream. This is the moment you arrive in Yukiguni, the Snow Country. For real, it’s a moment that lives in your head rent-free forever. This is the land that inspired the Nobel Prize-winning author Yasunari Kawabata, whose iconic novel, Snow Country (Yukiguni), isn’t just a book but a key that unlocks the soul of this region. We’re talking about Echigo-Yuzawa in Niigata Prefecture, the very town that served as the stage for Kawabata’s hauntingly beautiful tale of love, loss, and the transient nature of beauty. This isn’t just a ski trip, fam. This is a pilgrimage into the heart of a Japanese aesthetic, a chance to walk through the pages of a novel and feel the chill of the snow and the warmth of the sake that Kawabata wrote about with such devastating elegance. It’s about channeling that inner poet, that observer of fleeting moments, and finding your own story in a landscape sculpted by winter. This is your chance to step into the frame, to feel the poetic melancholy and the intense, vivid life that pulses beneath a blanket of pure white. This is where you come to understand a side of Japan that’s deep, quiet, and absolutely unforgettable.

After immersing yourself in this poetic landscape, you can extend the experience by exploring the cozy après-ski culture at a nearby destination, detailed in our guide to Nozawa’s izakaya hopping scene.

Through the Tunnel: Arriving in a Different Reality

The journey itself marks the first chapter of the story. Boarding the Joetsu Shinkansen amid the organized chaos of Tokyo Station, you sense the raw power of Japanese engineering. The train accelerates with a futuristic whisper as the urban landscapes of Saitama and Gunma prefectures blur past. It’s comfortable, efficient, and entirely modern. You might pick up an ekiben, a beautifully prepared station lunchbox, and a can of coffee, settling in for the ride. But as the train begins its climb into the mountains, a feeling of anticipation grows. The scenery becomes wilder, the towns smaller. Then comes the Dai-Shimizu Tunnel. At over 22 kilometers, it was once the world’s longest tunnel. Inside, the darkness is absolute—a sensory deprivation tank on rails, a moment for introspection. This is the border, the liminal space Kawabata described: “The train came out of the long tunnel into the snow country.” When you emerge, the contrast is so striking it feels like a cinematic reveal. The world you left behind—gray and brown—is completely erased, replaced by a universe of white. The snow isn’t just on the ground; it piles meters high on rooftops, clings to every tree branch, and softens every hard edge of the landscape into a gentle, curving masterpiece. The air outside the window appears different, denser, filled with a crystalline light. Stepping off the train at Echigo-Yuzawa Station is a full sensory experience. The cold hits first—not damp city cold, but crisp, clean, lung-cleansing cold scented with pine and purity. The station itself is a curious paradox. A modern hub designed to handle thousands of skiers and snowboarders, it still retains a distinct country charm. You’ll see people clomping around in heavy ski boots, gear slung over their shoulders, alongside locals going about their daily shopping. The scent of dashi broth from a noodle stand mingles with the faint, sweet aroma of sake from the station’s renowned tasting hall. Here, the dual spirits of Yuzawa—the high-energy winter sports haven and the quiet, reflective literary retreat—first converge. This arrival is more than a change of place; it’s a profound shift in awareness. The pace of life instantly feels altered. The silence, muffled by the thick snow, becomes a character in its own right. You’ve passed through the looking glass.

The Ghost of Komako: Living Inside the Novel

To truly capture the essence of Yuzawa, one must understand the story that made it famous. Yasunari Kawabata’s Snow Country is a subtle masterpiece, a novel grounded in atmosphere and unspoken feelings. It follows Shimamura, a wealthy and emotionally distant ballet critic from Tokyo, who visits a remote mountain onsen town. There, he encounters Komako, a local geisha, and their relationship unfolds as a delicate balance of attraction and distance, marked by brief, intense moments and long separations. Komako embodies tragic beauty—passionate and gifted, yet confined by her role in this secluded town. She offers herself fully to Shimamura, who only sees her as a fleeting, beautiful experience before returning to city life. Intertwined in their tale is the ethereal Yoko, a young woman with a hauntingly lovely voice, symbolizing a purer, more innocent kind of beauty. The novel focuses not on dramatic events, but on sensations—the cold of a winter night, a face reflected in a train window, the twang of a shamisen muffled by snow, and Komako’s “wasted effort” of passion. It embodies the Japanese aesthetic of mono no aware—a gentle sorrow for the transience of life—a feeling that saturates Yuzawa’s very air.

As an enthusiast of Chinese culture, I see a striking parallel with the classical Chinese notion of shāng gǎn (伤感), a beautiful, melancholic longing for moments doomed to fade. It’s a sentiment echoed in Tang dynasty poetry, in the sight of falling blossoms or farewells at a riverside pavilion. Kawabata uses this same emotional tone, but his ink is the snow of Niigata. Experiencing Yuzawa in winter allows one to feel this deeply—you might glimpse Komako’s ghost in steam rising from an onsen vent or hear Yoko’s voice echoing softly in the crisp night air. The ultimate pilgrimage site is the Takahan Ryokan, a traditional inn perched on a hill overlooking the town. Kawabata stayed here for years while writing the novel, and you can even book the very room he occupied, “Kasumi no Ma” (The Room of Mist). Sitting by the window, gazing out at the view that inspired him, offers a quietly spiritual experience. The room is preserved exactly as it was, complete with his writing desk and other relics. One can sense the weight of his words and the presence of his characters. The ryokan itself is a piece of living history, with creaking wooden floors, elegant tatami rooms, and a magnificent onsen. It’s an ideal refuge from the modern world, allowing visitors to tune in fully to the novel’s mood. Walking the silent, snow-covered streets at night, one can imagine Shimamura heading to a secret meeting, the crunch of his boots the only sound. The town becomes a personal film set, with you as its protagonist, witnessing quiet dramas unfold in the warm glow of lanterns against the cold, deep blue of a winter evening.

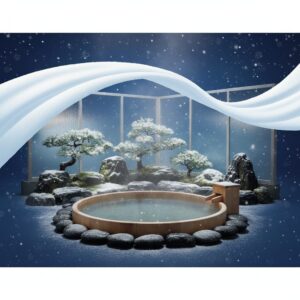

Onsen Flow: Soaking in the Soul of the Mountains

If the snow represents the body of Yukiguni, then the onsen—the natural hot springs—are its warm, beating heart. Truly, the onsen experience here is exceptional. It goes beyond simply taking a bath. In Japan, particularly in a place like Yuzawa, onsen is a ritual of purification, a way to connect with the earth’s volcanic energy, and a communal practice of deep relaxation. The mineral-rich water bubbles up from deep within the earth, carrying healing properties said to soothe muscles, soften skin, and calm the spirit. In a town buried under meters of snow, the onsen is not a luxury but an essential part of life, a necessary and cherished contrast to the biting cold outside. The experience begins even before you enter the water. There is quiet reflection in the changing room as you disrobe, leaving behind the modern world (and your phone). Then comes the ritual of kakeyu, using a small wooden bucket to pour hot water over your body, acclimating and cleansing yourself before stepping into the main bath. This small act of respect is central to onsen etiquette. And then, the moment of entry. The water is hot, sometimes startlingly so, but your body quickly adjusts, and a profound sense of release washes over you. All muscle tension, all travel stress simply melts away. The ultimate onsen experience in Yukiguni is the rotenburo, the outdoor bath. Stepping out into the freezing air and sinking into steaming water creates a sensory paradox that feels like pure magic. Imagine sitting in a stone-lined pool at a perfect 42 degrees Celsius while snowflakes drift down from the dark sky, melting on your face and shoulders. The world shrinks to the elemental contrasts of hot and cold, steam and snow, silence and the gentle lap of water. It is in these moments that you truly grasp the soul of this place. Yuzawa offers a variety of onsen to explore. While there are large, modern facilities linked to hotels and ski resorts, for a more local atmosphere, seek out the town’s public bathhouses, or soto-yu. Places like “Komako no Yu,” named after the novel’s heroine, provide a simple, authentic experience. For a more luxurious stay, a ryokan with its own private onsen is an unforgettable indulgence. The feeling after a long soak, known as yudate, is one of complete bliss. Your body is warm to the core, your skin tingles, and your mind is utterly clear. Wrapped in a cotton yukata, sipping on a cold glass of water or milk (a classic post-onsen drink), you feel entirely renewed. This ritual, repeated daily by locals, is the lifeblood of Snow Country—a constant source of warmth and community in the heart of winter.

The Art of White: Sake, Rice, and the Niigata Palate

If you believed that snow was the only significant form of white in Yukiguni, you’d be overlooking its liquid and solid counterparts: sake and rice. Niigata Prefecture is, without exaggeration, Japan’s undisputed sake capital. The secret behind its exceptional quality lies in the very snow that characterizes the region. In spring, vast amounts of snow melt into an abundance of incredibly pure, soft water that seeps through the mountains for months. This pristine water serves as the ideal ingredient for brewing premium sake. The other essential element is, naturally, rice. Niigata boasts Japan’s most coveted rice variety, Koshihikari, alongside several strains cultivated specifically for sake production, such as Gohyaku-mangoku. The blend of perfect water and rice, combined with centuries of brewing expertise, produces a sake style renowned across Japan: tanrei karakuchi, meaning light, crisp, and dry. This sake is exceptionally clean and smooth, crafted to enhance local dishes without overpowering them. The ultimate place to immerse yourself in this experience is the Ponshukan Sake Museum, conveniently located inside Echigo-Yuzawa Station. It’s a true haven for sake enthusiasts. For just 500 yen, you receive a small tasting cup (ochoko) and five tokens. You then enter a room lined with over 100 sake vending machines, each showcasing a different brewery from Niigata. Simply insert a token, place your cup, and press a button. It’s like a boozy library of regional terroir. You can spend hours here, comparing a crisp junmai from one valley to a fragrant daiginjo from another. It’s both an education and an adventure. They even offer a selection of salts from across Japan that you can sample to see how they alter the sake’s flavor profile. But don’t stop at the liquid. The rice itself is a revelation. You might think you know how rice tastes, but you haven’t truly experienced it until you’ve had a bowl of freshly cooked, top-grade Koshihikari grown in its homeland. The grains are plump, slightly sticky, and possess a natural sweetness and fragrance that is astonishing. Many local restaurants, or shokudo, serve simple teishoku set meals where the rice is the undeniable highlight. Paired with grilled fish, miso soup, and local mountain vegetables (sansai), it’s a meal that is straightforward, nourishing, and profoundly satisfying. Another local specialty to watch for is hegi soba. These soba noodles are made with a type of seaweed called funori, which gives them a wonderfully smooth, firm texture and a subtle green tint. They are served in elegant, bite-sized loops on a special wooden platter called a hegi. In the heart of winter, nothing compares to a steaming nabe hotpot filled with local mushrooms, vegetables, and meat, shared among friends in a cozy izakaya. The cuisine of Yukiguni is a direct reflection of its environment: hearty, pure, and deeply comforting.

Beyond the Page: Powder, Peaks, and Modern Yuzawa

While it’s easy to get swept away by the romantic, literary charm of Kawabata’s Yuzawa, the town’s other, more adrenaline-packed identity is impossible to overlook. Yuzawa is a powerhouse when it comes to winter sports. The same heavy, consistent snowfall that sets a moody tone for a novelist’s retreat also produces some of the best powder conditions worldwide. The area boasts over a dozen ski resorts, all conveniently accessible from the town center, earning it the nickname “the ski-resort condo capital of Japan.” The convenience is astounding. The GALA Yuzawa Snow Resort is so seamlessly connected that it has its own Shinkansen station. You can literally board a train in Tokyo in your street clothes and be on a ski lift less than 90 minutes later. It’s incredible. This creates a fascinating duality in the town’s vibe. There’s the quiet, reflective energy of the onsen and ryokan, alongside the lively, international buzz of the ski slopes. These two worlds coexist harmoniously. You could spend your morning carving fresh tracks in deep powder, thrilled by gliding down a mountain with panoramic views of snow-covered peaks, and then relax your afternoon away in a tranquil outdoor onsen, letting the day’s exertions dissolve. The resorts accommodate all skill levels, from complete beginners to expert freeriders. Kagura Ski Resort is renowned for its extensive backcountry access and long season, while family-friendly slopes can be found at places like NASPA Ski Garden. Evenings in Yuzawa blend both atmospheres. You might find lively apres-ski bars filled with skiers and snowboarders from around the world sharing tales of their day over beers and fried chicken. Or you could head to a small, quiet izakaya tucked away on a side street, enjoying a peaceful meal of local delicacies and warm sake, much like Shimamura and Komako might have done. Even if skiing isn’t your thing, taking a ride on one of the large ropeways, such as the one at Yuzawa Kogen, is worthwhile. The ascent provides breathtaking views, and from the summit, you can truly appreciate the vastness and grandeur of the Japanese Alps. In warmer months, when the snow melts, these same mountains transform into a haven for hikers, with lush green forests and fields brimming with alpine flowers. Yuzawa proves that you don’t have to choose between a quiet cultural retreat and an active mountain adventure—you can enjoy both here.

A Traveler’s Guide to the Snow Country

Getting lost in the poetry of a place is wonderful, but a bit of practical information goes a long way. Here’s the scoop on how to make your own Yukiguni journey a reality.

Access is Key

Traveling to Echigo-Yuzawa from Tokyo is incredibly easy and fast. The Joetsu Shinkansen (bullet train) runs directly from Tokyo Station and Ueno Station. The quickest trains, the Tanigawa and Toki, will get you there in about 75-90 minutes. It’s so fast that many skiers use it for a day trip, but to fully absorb the atmosphere, you should stay at least one or two nights. For international visitors, the JR Pass, JR East Pass, or the JR Tokyo Wide Pass can make this trip very cost-effective.

When to Visit

Snow Country is named for a reason. For the full deep-winter, Kawabata-inspired experience, the best time to visit is from late December through early March. January and February generally bring the heaviest snowfall, when snow walls can tower above you and the scenery is most dramatic. Serious skiers and snowboarders will find this prime powder season. If you prefer slightly milder weather and fewer crowds, but still plenty of snow, aim for early December or mid-to-late March. Spring (April-May) is also stunning, as the snow melts and cherry blossoms start blooming, creating a striking contrast between white peaks and pink flowers.

What to Pack: A Reminder

Never underestimate the cold and snow here. This isn’t the place for stylish sneakers and a lightweight jacket. Your usual city winter gear likely won’t suffice. Layering is essential. Begin with thermal base layers (top and bottom), add a mid-layer like fleece or a down vest, and make your outer layer waterproof and windproof—think ski jacket and pants, even if you’re not skiing. Crucially, wear insulated, waterproof boots with strong grip; streets can be icy, and you’ll be trekking through deep snow. A warm hat (beanie), waterproof gloves, and a scarf or neck gaiter are must-haves. Sunglasses or goggles are important too, as snow glare can be intense.

Choosing Your Base

Your accommodation choice will influence your experience. For a full cultural immersion, stay in a traditional ryokan. This means sleeping on a comfortable futon over tatami mats, enjoying exquisite multi-course kaiseki dinners in your room, and having access to the inn’s beautiful onsen. Takahan Ryokan is the ultimate spot for literary pilgrims. If you want something more modern and convenient, several hotels near the station are perfect for those planning train travel to multiple ski resorts. If your trip is all about the slopes, consider one of the large ski-in, ski-out resort hotels at the mountain base, which offer rentals, ski schools, and restaurants all in one place.

Li Wei’s Low-Key Tips for First Timers

- Slow Down and Savor. Yukiguni’s charm unfolds when you stop rushing. Find a café overlooking the mountains, order a coffee, and watch the snow fall for an hour. Let the peace seep into you. It’s a kind of meditation.

- Onsen Made Easy. Don’t be scared off by onsen etiquette. The basics are simple: wash thoroughly at the showers before entering the bath, keep your small towel out of the water (on your head or the side), and relax. No one’s watching. It’s a wonderfully freeing experience.

- Explore Ponshukan Boldly. Don’t just stick to the famous sake brands. Use your five tokens to try brews from unknown breweries. Ask staff for recommendations based on your taste. It’s a fun, low-pressure way to broaden your sake palate.

- Rice Matters. It may sound repetitive, but truly appreciate the rice when you order a meal. Savor its sweetness and texture before adding anything. It’s a simple perfection that anchors the entire regional cuisine.

- Do Your Reading. Read a few chapters of Snow Country before you arrive. You don’t need to be a literary expert, but carrying the novel’s images and moods with you will deepen your trip. It transforms the beautiful landscape into a living story rich with meaning and history.

The Lingering Afterglow

Leaving the Snow Country is the opposite of arriving. You board the train, warm to your core from one final soak in the onsen, your belly full of exquisite food and sake. As the Shinkansen glides back toward the long tunnel, you watch the white landscape fade away. The snow-covered houses, the silent forests, the steaming river—all slip past until darkness consumes them completely. When you emerge on the other side, returning to the familiar scenery of a Japan without snow, it feels like waking from a vivid dream. Yet, it’s a dream that lingers with you. The quiet of the snow, the intense warmth of the onsen, the pure taste of the sake, the melancholic beauty of Kawabata’s world—these sensations engrave themselves in your memory. Yukiguni is more than a place to see; it’s a place to experience. It reminds you of the beauty of impermanence, of the deep, quiet life that endures even under the harshest conditions. It’s a place that invites you to slow down, to observe, and to discover the poetry in simple, fleeting moments. You came searching for the ghost of a story, and in the end, you leave with your own. And you know, without question, that a part of your heart will remain there, forever waiting for the snow to fall again.