In the quiet backstreets of Kyoto, away from the vibrant flurry of geishas and the glowing lanterns of Gion, a different kind of sound can be heard. It is not the chime of a temple bell or the chatter of tourists. It is the sharp, resonant crack of bamboo on armor, the whisper of a blade being drawn from its sheath, and the thunderous, unified shout—a kiai—that seems to shake the very foundations of the old wooden building it comes from. This is the sound of a living history, the audible pulse of the samurai spirit that still beats strong in the heart of modern Japan. This is the world of the traditional dojo, a place that is far more than a mere training hall or gymnasium. A dojo, in its truest sense, is a “place of the Way,” a sanctuary where individuals embark on a profound journey of self-discovery, discipline, and connection to a warrior ethos that has been honed over centuries. To step inside is to step out of time, to breathe air thick with dedication, respect, and the faint, lingering scent of ancient cypress and unwavering resolve. For the traveler seeking more than just picturesque landscapes, for the soul yearning for a deeper understanding of Japanese culture, the dojo offers an unparalleled experience. It is an invitation to walk, even for a moment, in the footsteps of the samurai, to feel the weight of their legacy not as a story in a book, but as a visceral, challenging, and ultimately transformative reality. This guide is your portal into that world, an exploration of the echoes of the blade and the spirit that guides it, offering a path to understanding the heart of the warrior that lies dormant within us all.

To see how this enduring samurai spirit was reinterpreted for a modern audience, explore how 1960s yakuza films kept the warrior’s code alive.

The Soul of the Dojo: More Than Just a Training Hall

To truly grasp the profound experience of training in a traditional Japanese dojo, one must first let go of the Western gym concept. A dojo is not a casual workout space filled with loud music and mirrored walls for vanity. Instead, it is a sacred place, a forge where character and physical skill are shaped alike. The very atmosphere feels distinct—quiet, concentrated, and laden with unspoken rituals that have guided generations. Here, every object, every movement, and every corner holds significance, all aimed at the singular purpose of refining the self.

The Atmosphere of Stillness and Respect

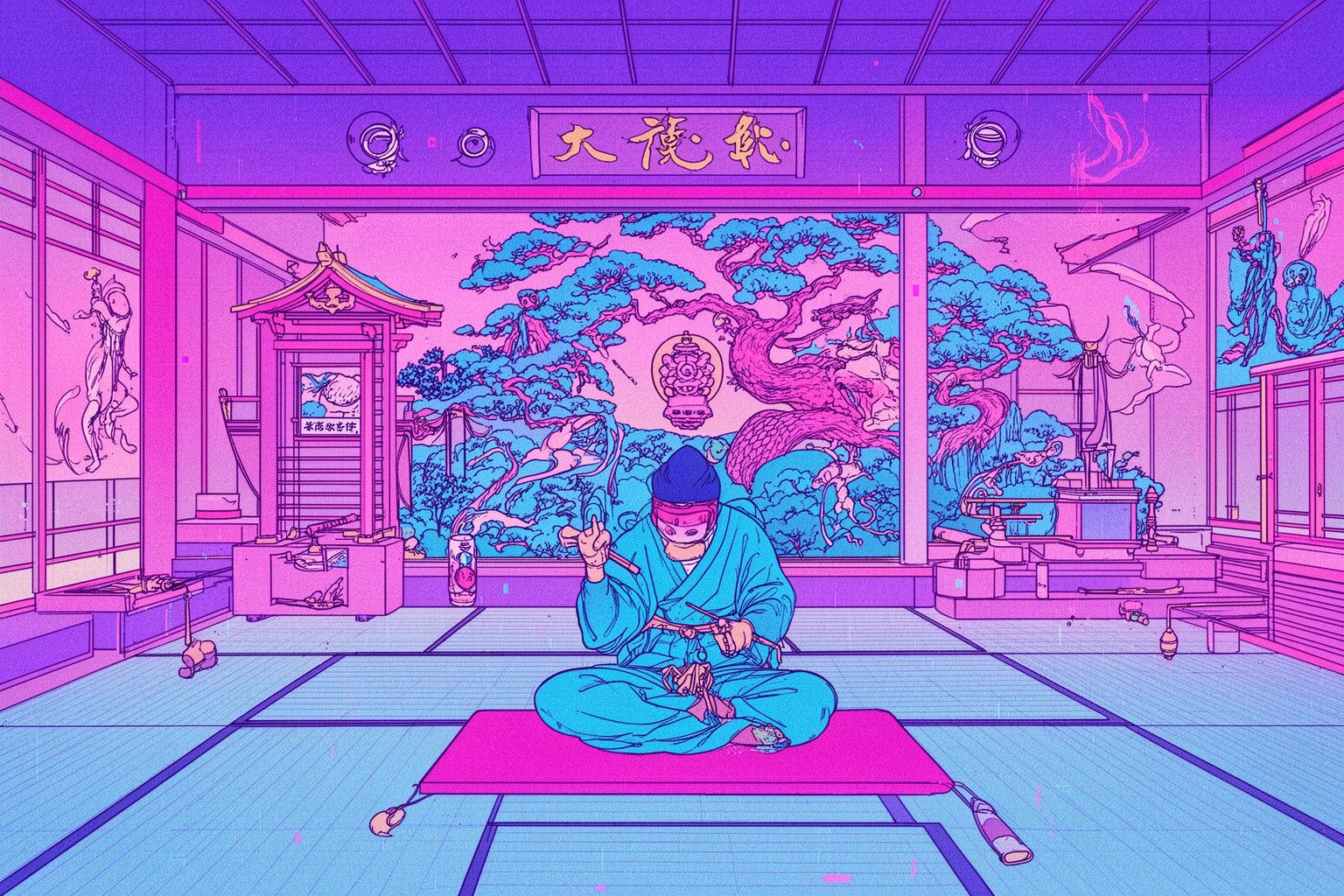

Upon entering a traditional dojo, one is immediately enveloped in sensory details. The prevailing scent is often that of aged wood—the dark, polished floorboards crafted from hinoki cypress or Japanese pine that carry the sweat and spirit of countless warriors. If tatami mats are present, a sweet, grassy aroma permeates the air, quintessentially Japanese and soothing. The space is uncluttered, minimalist, designed to remove distractions and encourage inward focus. Decorations tend to be functional or deeply symbolic: a carefully preserved suit of armor, rows of wooden weapons neatly placed in racks, and most importantly, the shomen. This front section of the dojo often features a small Shinto shrine called a kamidana, a piece of calligraphy expressing the dojo’s core principles, or a portrait of the martial art’s founder. It serves as the center of respect. Every entry and exit from the training area and every start and finish of class is marked by a deep, formal bow toward the shomen, known as rei. This is the foundation of dojo life—not a gesture of submission but one of heartfelt gratitude to the space, the art’s founders, the teachers, and the privilege to train. The silence inside a dojo can be as impactful as its noises. Between the sharp kiai and the clash of weapons, a profound stillness prevails—a shared focus so intense it almost feels tangible. Within this quiet, true training happens—the inner struggle with ego, fear, and fatigue.

The Architecture of Purpose

The design of a dojo is intentional and reflects its underlying philosophy. As noted, the shomen is the honored front of the room. The seat of highest respect, the kamiza or “upper seat,” is reserved for the head instructor, the sensei, symbolizing their role as guardian of the art’s teachings. Directly opposite the kamiza sits the shimoza, or “lower seat,” where students line up according to rank—from the highest-ranking senpai (senior students) closest to the kamiza to the newest kohai (junior students) at the far end. This seating arrangement, called za-rei, reinforces the hierarchy of experience and a mentorship system vital to learning. The senpai guide the kohai, who in turn learn from and honor those seniors. This structure is not about authority but about the orderly transmission of knowledge and responsibility. Typically, the dojo’s entrance is on a side wall to prevent anyone from walking directly across the central line between kamiza and shimoza, a path regarded as sacred. The walls are often bare except for racks holding weapons (katana, bokken, jo, shinai), which are treated with deep respect as extensions of the practitioner’s own body and spirit. Every element serves to nurture a mindset of humility, concentration, and reverence for the tradition one is about to embrace.

Echoes of the Samurai: Understanding the Spirit Within the Walls

The practices within a dojo go beyond mere physical exercises; they embody a living warrior philosophy that has influenced Japanese culture for nearly a millennium. To practice Kendo or Iaido is to enter into a direct dialogue with the samurai of old, feeling the principles they lived and died by flow through your own veins. This connection to history elevates martial arts training in Japan from a sport to a profound cultural and spiritual discipline.

From Battlefield to Path of Self-Perfection: The Evolution of Budo

Originally, Japan’s martial arts were known as bujutsu, meaning “martial techniques” or “military science.” These were practical, ruthlessly effective combat systems designed solely for survival on the battlefield. The samurai, Japan’s warrior class, mastered archery, horsemanship, swordsmanship, and various unarmed combat forms to serve their feudal lords. However, with Japan’s unification under the Tokugawa shogunate in the early 17th century, the country entered a prolonged era of peace. The samurai’s role as battlefield warriors waned, but their cultural and moral influence endured. During this period, a profound transformation took place. The focus of martial arts shifted from external conflict to internal struggle. The techniques of war (jutsu) evolved into paths of self-cultivation (do). Thus, Kenjutsu (the technique of the sword) became Kendo (the Way of the sword), and Iaijutsu became Iaido. This marked the birth of budo, the “martial Way.” The aim was no longer simply to defeat an opponent, but to overcome the self—to conquer one’s own ego, fear, anger, and doubt. The dojo became a laboratory for this inner alchemy, and rigorous physical training transformed into a vehicle for spiritual and moral development.

The Code of Bushido: Living Principles in Modern Practice

At the core of this transformation lies the unwritten code of the samurai, known as Bushido, or “the Way of the warrior.” Though often romanticized over time, its fundamental principles remain the ethical foundation of any traditional dojo. These are not abstract ideas to be memorized but virtues to be lived through every moment of practice. The seven virtues most commonly linked to Bushido are deeply ingrained in the training. Gi (Rectitude or Justice) is evident in strict adherence to dojo rules and fair treatment of training partners. Yu (Courage) is not aggression, but the resolve to confront your own fears and limitations on the mat, to push through exhaustion, and to face challenges with a calm heart. Jin (Benevolence or Compassion) is essential; despite the martial context, the ultimate goal is to protect and preserve life. This is expressed through careful control of techniques and a deep responsibility for your partner’s safety. Rei (Respect), as mentioned, is the visible expression of Bushido, guiding every interaction. Makoto (Honesty or Sincerity) means being true to yourself, your art, and your teacher. There are no shortcuts in the dojo; progress comes only from sincere, dedicated effort. Meiyo (Honor) involves upholding personal integrity along with the reputation of your dojo and art. Finally, Chugi (Loyalty) is demonstrated through unwavering commitment to your sensei and fellow students. These principles distinguish budo from mere sport. A technique performed without the proper spirit is regarded as hollow. The act of cleaning the dojo floor after practice, known as soji, exemplifies this perfectly. It is not a chore but an act of humility, gratitude, and a tangible expression of polishing one’s own spirit.

Choosing Your Path: An Introduction to Traditional Martial Arts

Japan presents a rich array of martial arts, each distinguished by its unique character, philosophy, and training methods. Selecting an art to pursue depends on your personal interests—whether you are attracted to the clash of swords, the silent elegance of the draw, the fluid dynamics of grappling, or the meditative concentration of archery. Each discipline offers a distinct perspective for exploring the principles of budo.

Kendo – The Way of the Sword

Entering a Kendo dojo, the quiet introspection typical of other martial arts gives way to intense energy. Kendo, the “Way of the Sword,” is the Japanese fencing art, practiced with a bamboo sword (shinai) and protective armor (bogu). The environment is charged, alive with the sharp sounds of shinai striking bogu and the powerful, guttural kiai accompanying each strike. The goal is not to slash recklessly but to deliver a perfect cut to a precise target with proper form, spirit, and posture, all executed in one unified motion. Kendo is a discipline of immediacy, teaching practitioners to overcome hesitation and commit wholly to the moment. The heavy, restrictive bogu creates a real sense of consequence, compelling you to confront the fear of being struck. Beyond the physical, Kendo is a profound mental discipline. Practitioners cultivate zanshin, a state of sustained awareness and alertness that continues after a technique is finished. It embodies decisiveness, maintaining calm amid chaos, and honoring one’s opponent as a partner in personal growth. A Kendo match begins and ends with a bow, serving as a powerful reminder that the true aim is not victory over another but mastery over oneself.

Iaido – The Art of Drawing the Sword

While Kendo is loud and outward, Iaido is its quiet, inward counterpart. Iaido, the “Way of Conscious Presence,” is the art of drawing the Japanese sword, or katana, from its scabbard (saya), delivering a cut, and returning it in one seamless motion. It is almost exclusively practiced solo, through kata, against one or more imaginary adversaries. The atmosphere in an Iaido dojo is one of deep meditative focus. Silence is broken only by the whisper of the blade leaving the saya and the soft swish cutting through the air. The emphasis is less on athleticism and more on precision, control, and spiritual refinement. Each kata tells a complete story, a scenario demanding perfect form, a composed mind, and resolute spirit. The true opponent in Iaido is the self—the restless mind, the tense shoulder, the uneven breath. This practice is a moving meditation requiring intense mindfulness to harmonize body, mind, and sword. Iaido teaches presence in every moment, finding beauty in efficiency, and understanding that the highest victory is a conflict resolved without ever drawing the blade. It is an intimate and reflective art, a dialogue with the history and spirit of the samurai sword.

Aikido – The Way of Harmonious Spirit

Aikido is a distinctly modern budo, created in the early 20th century by Morihei Ueshiba. Its philosophy sets it apart from many other martial arts. Aikido, the “Way of Harmonious Spirit,” focuses not on defeating an opponent but on blending with their movement and energy to neutralize attacks without inflicting serious harm. It is a purely defensive discipline encompassing a sophisticated system of throws, joint locks, and pins that redirect an attacker’s momentum. The atmosphere in an Aikido dojo is cooperative and fluid. Training is done with a partner, but the relationship is not adversarial. Instead, practitioners collaborate to understand movement and energy principles. The techniques are circular and graceful, resembling a dance more than combat. Traditional Aikido has no competitions, as the concept of winning and losing contradicts its core philosophy of harmony. Training cultivates centeredness and calm under pressure, encourages peaceful conflict resolution, and fosters a spirit of compassion. It physically embodies the principle that yielding can be more powerful than resisting, making it a profound practice for both self-defense and daily life.

Judo – The Gentle Way

Renowned worldwide as an Olympic sport, Judo has deep roots in the samurai tradition of jujutsu. Developed by Professor Jigoro Kano in the late 19th century, Judo, or the “Gentle Way,” revolutionized martial arts training by establishing a pedagogical approach prioritizing safety and mutual benefit. The core principle of Judo is seiryoku zen’yo, or “maximum efficiency, minimum effort.” It teaches a smaller person how to overcome a larger, stronger opponent by using leverage, balance, and momentum. A Judo dojo is a place of intense physical effort and strict discipline. The continual sound of bodies hitting tatami mats underscores the importance of learning to fall safely (ukemi), a skill practiced relentlessly. Training centers around randori, or free practice, where judoka apply throwing and grappling techniques against resisting opponents. Despite its physical nature, the spirit remains one of respect and shared learning. Judo’s motto, jita kyoei, means “mutual welfare and benefit,” emphasizing that practitioners are responsible for each other’s growth and safety. Through rigorous practice of throws and holds, judoka develop perseverance, discipline, and a deep understanding of their bodies and the physics of movement.

Kyudo – The Way of the Bow

Perhaps the most meditative and ritualistic among Japanese martial arts, Kyudo is the “Way of the Bow.” More than simple archery, Kyudo aims not just at hitting the target but at achieving truth, beauty, and goodness through a perfect shot. The process, form, and mindset of the archer are paramount. The Kyudo dojo, or kyudojo, embodies profound stillness and aesthetic grace. Archers dressed in traditional attire move with slow, deliberate elegance through the Hassetsu, the eight fundamental stages of shooting. Each stage, from preparing the bow to releasing the arrow, is a ritual intended to unify mind, body, and spirit. The atmosphere is solemn and introspective, with only the breath of the archer, the creak of the silk bowstring, and the satisfying thud of the arrow hitting the target as sounds. A central tenet in Kyudo is shahin-shaho, “correct shooting is correct hitting,” meaning that when the archer’s spirit is true and form flawless, the arrow naturally finds the target’s center. Conversely, hitting the mark with a disturbed mind or poor form is considered meaningless. Kyudo powerfully cultivates patience, unwavering focus, and profound inner calm.

Stepping onto the Tatami: A Practical Guide for the Intrepid Traveler

Embarking on a journey into the world of Japanese budo can be daunting for a foreigner. The language barrier, complex etiquette, and intense training may seem like overwhelming challenges. However, many dojos warmly welcome sincere visitors who approach the experience with humility and a genuine eagerness to learn. With proper preparation and mindset, a short-term training experience can become one of the highlights of your trip to Japan.

Finding an Authentic Experience

A quick online search will show many “samurai experiences” aimed at tourists. While enjoyable, these tend to be brief and superficial. For a truly authentic immersion, your goal should be to find a genuine local dojo and join a regular class. Though this takes more effort, it offers far greater rewards. Start by researching dojos in the city you plan to visit. Cities with rich martial histories like Kyoto, Kamakura, and Tokyo are excellent places to begin. Look for dojo websites with English pages or those explicitly welcoming international visitors (gaikokujin kangei). Many dojos offer a trial class called taiken nyumon for a small fee—an ideal way to experience training without a long-term commitment. Alternatively, some organizations and tour companies specialize in connecting foreign visitors with traditional dojos, managing communication and logistics on your behalf. When contacting a dojo, be polite and clearly express your intentions: that you are visiting Japan, have a sincere interest in their art, and would be honored to observe or participate in a class. Even with limited Japanese, learning a few key phrases like “Yoroshiku onegaishimasu” (I look forward to working with you) and “Arigato gozaimashita” (Thank you very much) will greatly demonstrate your respect.

The Unspoken Rules: Dojo Etiquette (Reigi)

Etiquette, or reigi, is not merely a set of arbitrary rules but a vital part of dojo training. Observing proper reigi shows your sincerity and respect for the tradition you are entering. Your adherence to these customs will be valued far more than any physical skill you might have. From the moment you arrive, your training begins. First, remove your shoes at the entrance in the designated genkan area, placing them neatly together with the toes pointing outward. You will enter the dojo wearing socks or barefoot. Before stepping onto the training area (tatami or wooden floor), perform a standing bow (ritsurei) toward the shomen, a sign of respect for the space and the art. If given a training uniform (keikogi or dogi), there is a proper way to wear and fold it. Observe others or politely ask for assistance. The belt, or obi, is tied in a specific knot and should never touch the floor. During class, address the head instructor as “Sensei” and senior students as your senpai. Maintaining a respectful and attentive attitude toward them is essential. When the sensei demonstrates a technique, sit quietly and attentively in the formal kneeling position called seiza. If seiza is uncomfortable, sitting cross-legged is usually acceptable, but avoid slouching, leaning against a wall, or sprawling disrespectfully. When practice begins, bow to the shomen, then to the sensei and fellow students. When partnering, bow to your partner before and after practicing together. Finally, at class end, don’t be surprised if everyone grabs a cleaning cloth (zokin) and begins wiping the floor. This ritual cleaning, or soji, is a meaningful way to show gratitude and become part of the group through enthusiastic participation.

What to Expect in Your First Class

Your first class will challenge you both physically and mentally. Expect to feel clumsy, confused, and completely out of your element—this is normal and anticipated. The key is to approach it with an open mind—empty your ego and be ready to learn. Classes typically start with warm-up exercises (junbi undo), including stretching, conditioning, and basic movements specific to the art. The main focus will be on kihon, fundamental techniques, often practicing one simple movement repeatedly. This repetition forms the foundation of mastery in budo. Don’t get frustrated by the emphasis on basics; listen carefully to the sensei’s instructions. If you don’t understand Japanese, watch their movements intently. Much teaching in a dojo is non-verbal. The sensei may adjust your form physically—this shows care, not criticism. Be prepared for physical exhaustion, as training uses muscles you didn’t know you had. Yet, you will also experience a profound sense of achievement. The atmosphere, while serious and disciplined, is also supportive and communal. Your fellow students were all beginners once and will empathize with your struggles. Your willingness to try, persevere, and show respect will earn their admiration. Your goal in the first class is not to excel but to be present, humble, and absorb as much of the unique atmosphere as possible.

Beyond the Dojo: Integrating the Warrior’s Path into Your Travels

The lessons and spirit of the dojo need not remain confined within its walls. By integrating related cultural and historical explorations into your Japanese itinerary, you can deepen your understanding of the warrior ethos. Complementing your physical training with visits to places where samurai lived, fought, and sought spiritual guidance will greatly enrich your experience, transforming it from a simple practice into a comprehensive cultural immersion.

Visiting Historical Sites of the Samurai

To grasp the world that gave rise to these martial arts, walk the same grounds the samurai once did. Explore one of Japan’s stunning original castles, such as Himeji Castle in Hyogo, known for its striking white walls and intricate defensive designs, or Matsumoto Castle in Nagano, also called the “Crow Castle” for its dark exterior. As you wander their wooden corridors and steep staircases, you might almost hear the clang of armor and sense the strategic minds of the warriors who defended these fortresses. Visit preserved samurai districts (buke yashiki), like those in Kakunodate or Kanazawa. Walking these tranquil streets lined with mud walls and elegant wooden homes offers insight into the daily lives of the warrior class. For those fascinated by the history of swordsmanship, the Japanese Sword Museum in Tokyo displays an impressive collection of blades, highlighting the artistry and spirit embedded in the katana. Visiting these sites creates a tangible link to the past, allowing you to better understand the environment that shaped the techniques and philosophies you practice in the dojo.

The Philosophy of Zen and Budo

The relationship between Zen Buddhism and the samurai lifestyle is deep and inseparable. Zen principles such as mindfulness, self-discipline, and acceptance of impermanence formed the ideal philosophical and psychological foundation for warriors confronting the ever-present possibility of death. To further explore this connection, spend time in the calm, contemplative spaces of Zen temples. In Kyoto, temples like Ryoan-ji, famous for its mysterious rock garden, and Kennin-ji, the city’s oldest Zen temple, provide serene settings for reflection. In Kamakura, the former shogunate capital, Kencho-ji and Engaku-ji served as important Zen centers for the warrior class. Many temples offer zazen (seated meditation) sessions to visitors. Engaging in zazen can powerfully complement your physical training. The practice of calming the mind, observing thoughts without judgment, and concentrating on the breath is the internal counterpart to the physical discipline learned in the dojo. This combined practice of moving meditation (budo) and still meditation (zazen) can foster a more holistic understanding of the warrior’s path to enlightenment and self-mastery.

Your experience in a traditional Japanese dojo is far more than a simple travel activity; it is a pilgrimage to the heart of a culture. It presents the chance to challenge your body, sharpen your mind, and connect with a lineage of discipline and philosophy that spans centuries. The echoes of the blade resonate not only in the clash of steel but also in the silent bow, the meticulously cleaned floor, and the unwavering gaze of a sensei. The samurai spirit is not a relic of the past but a living principle that you can sense in your own posture, your breath, and your emerging clarity and purpose. While you may leave Japan with sore muscles and a few bruises, you will also carry something far more enduring: a deeper respect, the quiet confidence born of discipline, and the understanding that the “Way” is not a destination but a path to be walked—one focused, sincere step at a time. That first step awaits you on a polished wooden floor, in the profound and powerful stillness of the dojo.