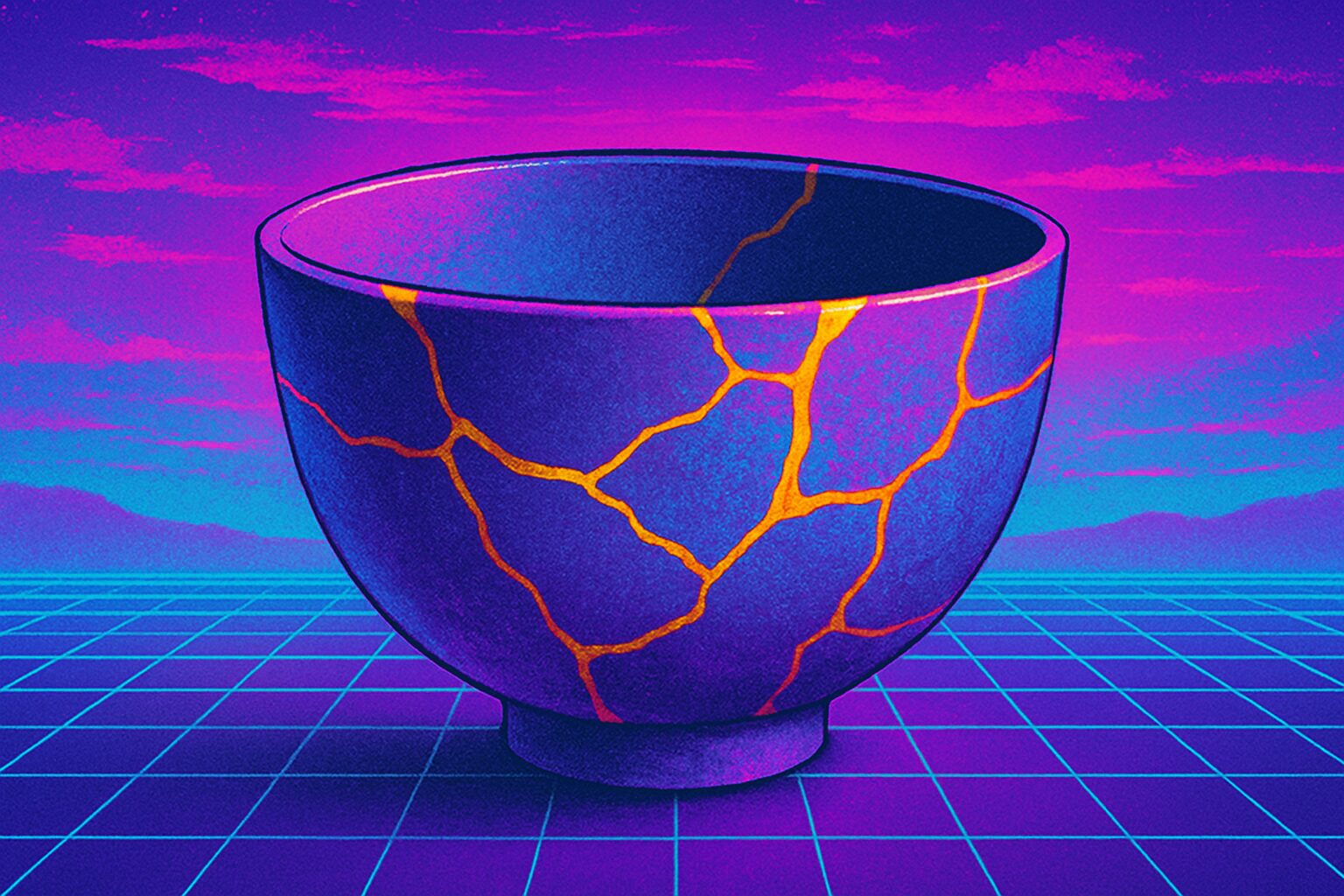

Yo, what’s up, world explorers! Yuki here, your go-to guide for all things Japan. Let’s spill the tea on something that’s low-key one of the most beautiful concepts to come out of this country. Picture this: your absolute favorite ceramic bowl, the one you use for literally everything, slips from your hands. It shatters on the floor. Heartbreak, right? The end of an era. In most places, that’s a one-way trip to the trash can. But here in Japan, we see that differently. We’re like, “Nah, this isn’t an ending. It’s the origin story.” This is where the magic of Kintsugi comes in, and trust me, the glow-up is real. Kintsugi, or ‘golden joinery,’ is the centuries-old art of repairing broken pottery not by hiding the cracks, but by celebrating them. It’s about mending the pieces with a special lacquer mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum. The result isn’t just a fixed bowl; it’s a new piece of art with a story etched in gold. It’s a whole mood, a philosophy that says our scars, our history, our imperfections are what make us beautiful. It’s about resilience, for real. Before we dive deep into this lit art form, let’s get you grounded. Many of the most amazing Kintsugi workshops and galleries are vibing in cultural hubs like Kyoto, where ancient traditions are still part of the daily rhythm. Check the map below for a spot where you can catch this vibe live.

The Vibe: More Than Just Glue and Gold

So, before diving into the details of how it’s done, you need to grasp the philosophy behind Kintsugi. It’s not merely a craft; it’s a way of seeing the world. This practice is deeply tied to the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi, a concept that appreciates beauty in things that are imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. Imagine an old, moss-covered stone in a tranquil temple garden or a handmade tea bowl that fits perfectly in your hands despite its slightly off-center shape. That’s wabi-sabi. It’s about valuing the beauty of age and wear, the story an object tells through its existence. Kintsugi is essentially wabi-sabi in practice. The break isn’t a flaw to hide—it’s part of the object’s history and unique journey. By highlighting the cracks with gold, the artist declares, “This is what you’ve been through, and it has made you more beautiful, not less.” It’s a powerful message, no doubt.

Another key idea is ‘mottainai,’ a term that’s difficult to translate directly but conveys a deep regret over waste. It’s that feeling when you see something with potential—whether food, time, or an object—being discarded carelessly. Mottainai is a Buddhist concept encouraging us to recognize the value in things and use them fully. When a ceramic piece breaks, the mottainai spirit says it’s not over—the piece’s life continues. It can be reborn into something new, imbued with even more character. Finally, there’s the Zen concept of ‘mushin,’ or ‘no mind,’ which is about accepting change and fate, flowing with life as it unfolds. A bowl breaking is beyond our control, and rather than resisting or despairing, mushin teaches acceptance. Kintsugi embodies this acceptance physically, taking the unexpected damage and integrating it into a new form. The mind clears of attachment to perfection and embraces reality as it is, cracks and all. It’s a meditation on letting go and finding peace in the present moment.

A History Forged in Tea and Philosophy

So, where did this legendary idea originate? Let’s travel back in time. The story everyone shares places the birth of Kintsugi in the late 15th century, during Japan’s Muromachi period. The central figure in this tale is Ashikaga Yoshimasa, the 8th shogun of the Ashikaga shogunate. He was an avid patron of the arts, far more interested in culture than in politics or governance. He was captivated by the Japanese tea ceremony, which was becoming highly stylized and influential at that time.

The tale says that Yoshimasa owned a beloved celadon tea bowl from China, a highly prized piece. By unfortunate luck, it broke. Heartbroken, he sent the fragments back to China, hoping their expert craftsmen could restore it. When it returned, it had been mended with unsightly metal staples. It was usable, but the aesthetic was completely lost. The shogun was extremely disappointed—it simply lacked the same graceful beauty. This saddened shogun then challenged his own Japanese artisans to devise a more beautiful and artistic way to repair it. Thus, Kintsugi was born. They not only repaired the bowl but transformed it, using precious urushi lacquer and powdered gold to trace the cracks, turning the damage into the bowl’s most breathtaking feature. The shogun was delighted, and a new art form emerged. This moment marked the start of a shift in Japanese aesthetics, embracing a type of beauty very different from the perfect, symmetrical forms esteemed in China.

This art form perfectly complemented the rising tea ceremony culture. Tea masters began to value Kintsugi-repaired items deeply. A broken and restored tea bowl carried more character and history, considered more precious than a flawless one. Some collectors became so passionate that they were rumored to deliberately break valuable pottery just to have it repaired with Kintsugi, thereby enhancing its aesthetic value. Such was the depth of the obsession. The art became more than repair; it was a profound statement, embodying philosophical ideas circulating in Zen Buddhist circles and among cultural elites. It celebrated the beauty found in the marks of time and experience.

The Soul of Kintsugi: Urushi Lacquer

Let’s get technical for a moment, as the core material in traditional Kintsugi is truly remarkable. This isn’t just any glue from a hardware store. The key ingredient is urushi, the sap harvested from the Japanese lacquer tree, which is related to poison ivy. Yes, you read that right. In its raw state, urushi can cause severe rashes, and craftsmen build immunity through years of careful handling. But this substance is extraordinary—completely natural, food-safe, waterproof, and incredibly strong and durable. Once cured, it can last hundreds or even thousands of years. Archaeologists have unearthed 9,000-year-old objects coated with urushi that remain in excellent condition. It’s a living material.

Harvesting urushi is a meticulous task. Craftsmen make precise incisions in the tree’s bark to collect the slow-dripping sap, drop by drop. Each tree produces only a small quantity annually, making urushi a precious resource. The curing process is equally unique. Urushi doesn’t dry conventionally; it hardens through a chemical reaction that needs high humidity and warmth. Craftsmen use a special wooden chamber called a ‘muro’ to create this ideal environment, allowing the lacquer to cure properly, sometimes over days or weeks per layer. This slow, deliberate method is fundamental to Kintsugi’s discipline. It cannot be rushed; it teaches patience and respect for natural materials and processes. Urushi itself becomes part of the art, not merely a tool. It is the lifeblood that runs through the repaired cracks of the ceramic, lending it new strength and a renewed story.

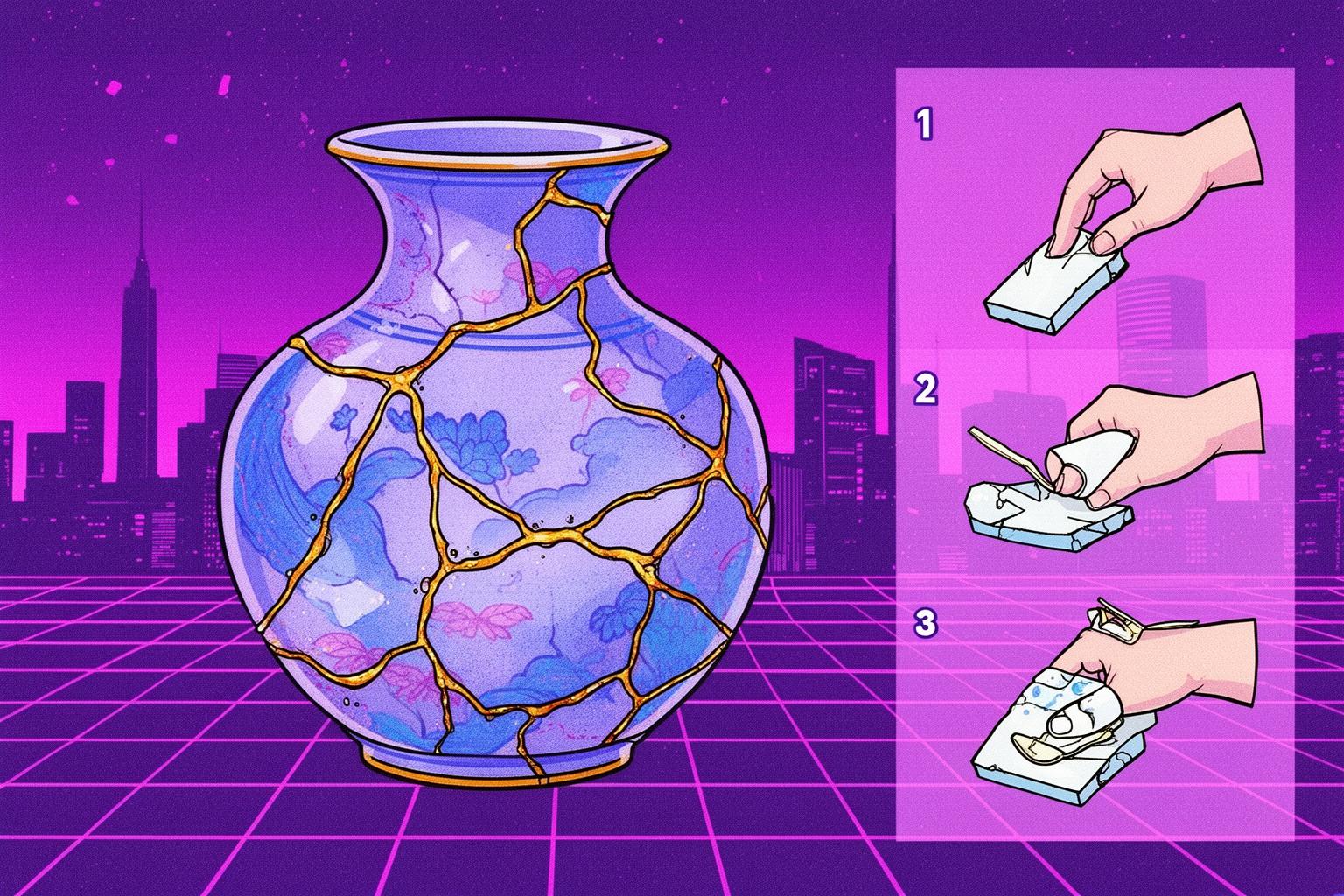

The Art of the Process: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

The actual practice of Kintsugi is a true lesson in patience. It’s a slow, meditative process that can take weeks or even months to finish just one piece. It’s not a quick repair; it’s a rebirth. Let’s explore the transformation, step by step.

Step 1: The Gathering

First, all the broken fragments must be collected, including the tiniest shards. This is a moment of acceptance. You observe the shattered pieces and choose not to discard them but to honor their existence. Each piece is meticulously cleaned and prepared for reunion.

Step 2: Making the First Bond

The initial adhesive, called ‘mugi-urushi,’ is created by mixing raw urushi lacquer with rice or wheat flour to form a sticky, strong paste. The craftsman carefully applies this paste to the edges of the broken fragments. This step demands intense concentration. The pieces must be aligned precisely, reconstructing the object’s original shape as closely as possible. Once joined, the pieces are held together and placed in a ‘muro’ to cure. This initial bond lays the foundation for the entire repair.

Step 3: Filling the Voids

Pieces rarely break cleanly; chips, gaps, and missing fragments are common. This is where ‘sabi-urushi’ is used. It’s a putty-like paste made by mixing urushi with finely powdered stone or clay. The craftsman applies it to fill the gaps, layer by painstaking layer. Each layer must be thin and fully cured before the next is applied. After curing, each layer is sanded smooth with tools like charcoal. This often becomes the most time-intensive part of the process—a slow sculpting that rebuilds new ground to bridge the old.

Step 4: The Lacquer Coats

Once the voids are filled and the surface is perfectly smooth, the real artistry begins. The craftsman applies multiple coats of urushi lacquer over the seams. This typically starts with a black or dark-colored urushi layer, which is then cured and polished. Next, a final coat of red or black lacquer, called ‘e-urushi,’ is applied. This layer is the base for the gold to adhere to and must be flawlessly smooth, as any imperfection will be visible in the final gold lines. The color of this undercoat can subtly influence the shade of the gold, a nuance that masters skillfully exploit.

Step 5: The Golden Moment

This is the peak of the entire process and what gives Kintsugi its name. Timing is critical. The craftsman applies the final red lacquer layer and waits for it to reach the perfect tacky state—neither too wet nor too dry. This window can be brief. Then, using a fine brush or a special bamboo tube called a ‘makizutsu,’ finely powdered gold is delicately sprinkled onto the tacky lacquer. The gold adheres to the urushi, forming the iconic shimmering lines. Excess gold is carefully brushed away with a soft silk brush.

Step 6: The Final Polish

After the gold has set and the lacquer is fully cured, the final step follows. The golden lines are gently burnished using a specialized tool, often an agate stone or a piece of ivory. This polishing reveals the rich, deep shine of the gold, allowing it to gleam vividly against the ceramic. The piece is now reborn; it’s more than repaired—it’s transformed, bearing the radiant scars of its history. Each step is a ritual, a silent dialogue between craftsman and object, a meditation on healing and beauty.

More Than One Way to Mend: The Styles of Kintsugi

Kintsugi is not a one-size-fits-all technique. Different methods or styles are employed depending on the nature of the break and the artist’s vision. It’s a creative journey, and the choices made can dramatically influence the final character of the piece.

The Crack (Hibi)

This is the most common style. It’s used when there is a simple crack without missing fragments. The craftsman traces the fine crack line with gold, turning the fissure into an elegant, vein-like pattern. It’s a minimalist approach that subtly highlights the break with grace.

The Piece Method (Kake no Hoshū)

When a large section is missing, it can’t simply be glued back. This technique involves reconstructing the entire missing fragment. Instead of replacing it with ceramic, the void is filled with a mixture of urushi and gold (or sometimes just urushi lacquer alone). The result is a solid gold patch—a bold, dramatic statement that doesn’t conceal the loss but makes it a focal point.

The Joint-Call (Yobitsugi)

This technique is where Kintsugi becomes especially inventive, and honestly, it’s my favorite. ‘Yobitsugi’ means “to call in a joint.” Here, a missing piece is replaced with a shard from a completely different, unrelated piece of pottery. Imagine repairing a simple white bowl with a fragment from an ornate, blue-patterned plate. It’s a collage, a mashup. The craftsman creates a new hybrid, carrying the histories of two separate objects. It’s a celebration of diversity and the beauty born from uniting different pasts into a new whole. It stands as a powerful metaphor for connection, creating family from disparate parts. These yobitsugi repairs often end up the most dynamic and surprising, showcasing the boundless creativity of the Kintsugi spirit.

Kintsugi in the 21st Century: A Vibe for Modern Life

So why is this ancient art form experiencing a resurgence worldwide right now? Because its message has never been more relevant. In a world obsessed with perfection, filters, and masking our flaws, Kintsugi offers a refreshing perspective. It stands as a rebellion against the throwaway culture that urges us to discard anything broken or old.

Kintsugi as a Metaphor for Healing

The link to mental health and personal healing is significant. More people are beginning to view their emotional scars and traumas through the lens of Kintsugi. We all have experienced things that have ‘broken’ us in some way. The philosophy of Kintsugi encourages us not to be ashamed of these scars but to embrace them as part of our story. They serve as proof of our resilience and evidence that we have survived and healed. The process of mending ourselves, integrating past experiences, can be seen as a form of Kintsugi in itself. Our struggles do not make us ‘less than’; instead, they make us more interesting, complex, and beautiful. The gold symbolizes the self-love, wisdom, and strength gained from our experiences. This concept of ‘post-traumatic growth’ is a core principle in modern psychology, and Kintsugi is its perfect artistic embodiment.

A Stand for Sustainability

In an era dominated by fast fashion and disposable goods, Kintsugi stands as a powerful symbol of sustainability. It promotes repair instead of replacement. It invites us to consider the history and future of the objects we own. Rather than discarding something, can we breathe new life into it? This mindset directly challenges consumerism, advocating for a slower, more mindful lifestyle that values both possessions and the resources used to create them. The ‘repair culture’ is expanding worldwide, with Kintsugi as its spiritual guide. It demonstrates that repairing is not a compromise but an act of elevation, making the object even more valuable than before.

Inspiring Modern Art and Design

Contemporary artists and designers are fully embracing the Kintsugi movement. Its influence is visible everywhere. Fashion designers are crafting garments with intentional, beautiful mending. Jewelers are applying Kintsugi techniques to repair precious stones. Interior designers are commissioning Kintsugi-repaired pieces as bold statements. Artists are producing large-scale installations inspired by the concept of beautiful repair. Kintsugi has transcended traditional craft and become a global aesthetic and philosophical movement, proving the timelessness of its message. The idea of finding beauty in the broken is a universal theme that resonates across cultures and backgrounds.

Getting Hands-On: Your Guide to Experiencing Kintsugi in Japan

Reading about Kintsugi is one thing, but experiencing it firsthand offers an entirely different perspective. If you’re visiting Japan, immersing yourself in this art form is a must. Here’s how you can do it.

Take a Workshop

This is the best way to truly grasp the spirit of Kintsugi. Workshops tailored for travelers are available in major cities like Kyoto, Tokyo, and Kanazawa. They range from brief, two-hour sessions to more intensive, multi-day courses.

Keep in mind that most short workshops for tourists don’t use traditional urushi since it takes a long time to cure and may cause allergic reactions. Instead, they use modern, safe materials such as synthetic lacquers and epoxy resins, often called ‘modern Kintsugi.’ While it lacks the deep historical significance, it’s a fantastic way to learn the basic techniques and philosophy. You’ll get to repair a broken piece of pottery and leave with a beautiful handmade souvenir. It’s incredibly rewarding and will deepen your appreciation for the craft.

If you’re serious about mastering the traditional method, you’ll need to find a more specialized, longer course. These are rarer for tourists but definitely worth it if you have the time and dedication. Just be sure to wear old clothes—urushi is not to be taken lightly!

Visit Museums and Galleries

To admire true Kintsugi masterpieces, visit some of Japan’s remarkable museums. Seek out collections of Japanese ceramics and tea ceremony utensils. The Nezu Museum and the Gotoh Museum in Tokyo, along with many temples and galleries in Kyoto, frequently display stunning examples. When observing a piece, study it closely. Notice the story it tells—is it a delicate crack, a bold streak of gold, or a creative yobitsugi repair? Reflect on the tea master who may have held that bowl centuries ago, admiring the same golden lines. It creates a powerful link to the past. The repair is an essential part of the object’s identity, just as significant as its original glaze or form.

Buying Authentic Kintsugi

If you want to bring a piece of Kintsugi home, be a discerning buyer. There’s a clear distinction between traditional repairs and modern decorative items. Authentic Kintsugi, which uses real urushi and gold, is an investment. It’s costly due to the time, skill, and precious materials involved. You’ll find these pieces in high-end craft galleries and specialty stores. If you find something inexpensive, it’s likely made with modern glue and imitation gold paint. That’s fine if you simply want a decorative souvenir, but it’s important to know what you’re purchasing. Ask the gallerist about the materials and artist. A genuine Kintsugi piece is not just an object; it’s a functional work of art with a profound philosophical story.

First-Time Tips and Tricks

- Book in Advance: Kintsugi workshops, especially those conducted in English, are popular. Reserve your place online well before your trip to avoid missing out.

- Be Patient: Whether you’re in a workshop or simply appreciating the art, remember that Kintsugi is about the slow, deliberate process. Don’t rush; embrace the meditative pace of the craft.

- Ask Questions: Japanese craftsmen and gallery owners are often passionate about their work. If you show sincere interest, they’ll gladly share their knowledge. Don’t hesitate to ask!

- Look Beyond the Gold: While the golden lines are captivating, focus on the ceramic piece itself. The true beauty of Kintsugi lies in the harmony between the original object and its repair. The gold should enhance, not overpower, the piece.

A Final Thought on Beautiful Scars

Kintsugi is far more than just a repair technique. It represents a subtle revolution in how we perceive the world. It teaches us that neither objects nor people need to be discarded when broken. It reveals that the journey, with all its bumps, breaks, and detours, is what creates genuine, lasting beauty. The next time you notice a crack in the pavement, a scar on your skin, or a painful memory, consider Kintsugi. Imagine filling that crack with gold, honoring the story it holds. It reminds us that healing isn’t about erasing the past; it’s about embracing it as part of who we are and shining brighter because of it. It’s a declaration: “I am beautiful, not despite my history, but because of it.” And that, my friends, is a philosophy capable of transforming your entire world. So go ahead, embrace your golden cracks, and keep exploring.