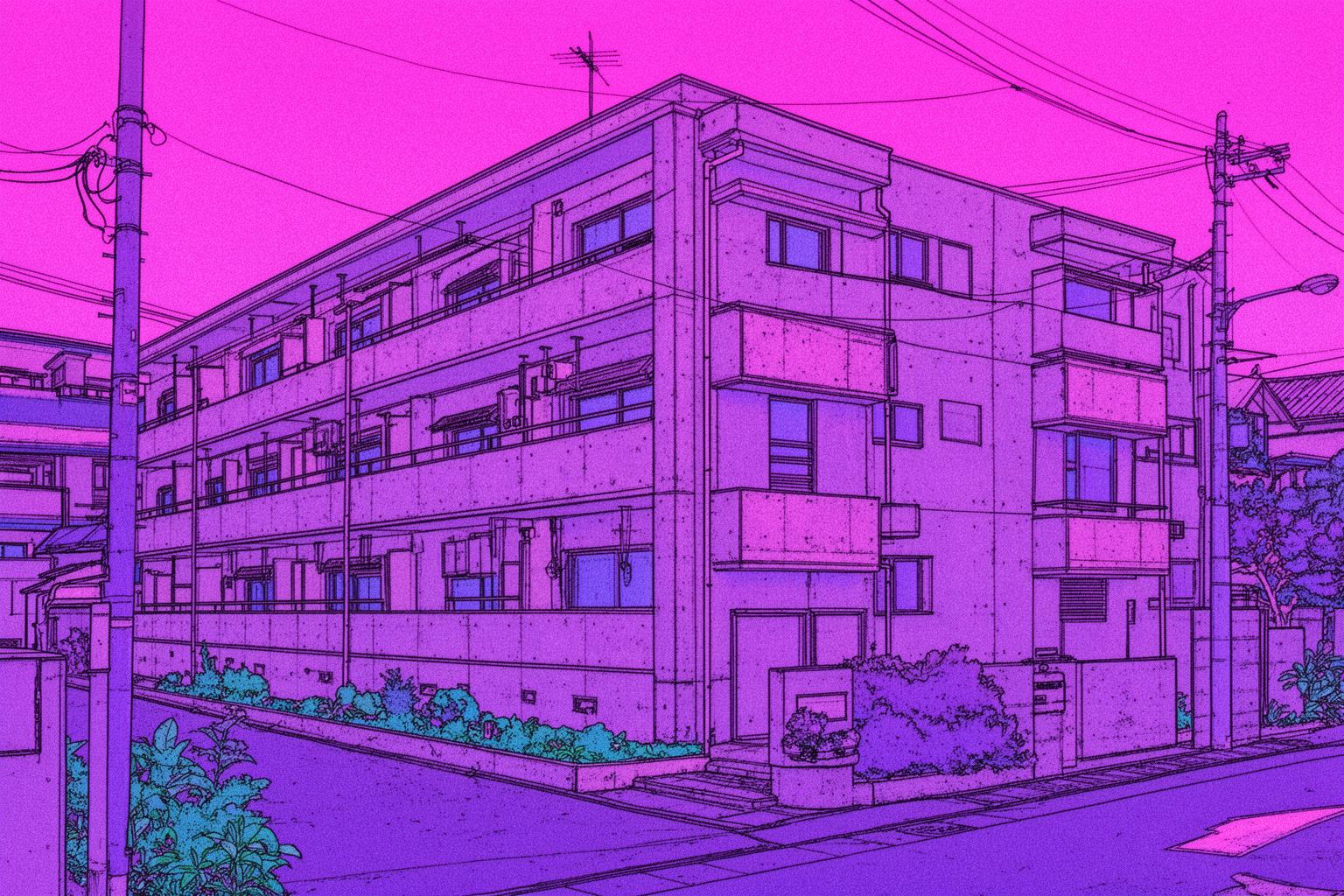

Yo, let’s have a real talk. When you picture Japan, what pops into your head? Cherry blossoms doing their pretty pink thing? Ancient temples where the vibes are just… serene? Maybe the electric neon chaos of a Tokyo crossing? That’s all legit, it’s all part of the magic. But what if I told you there’s another layer to this place, a concrete kingdom hiding in plain sight that’s straight out of a sci-fi flick? I’m talking about a Japan that feels less like a postcard and more like a panel from Akira or a frame from Blade Runner. This is the world of the Showa-era Danchi, Japan’s sprawling public housing complexes. These aren’t your average apartment blocks; they are titans of concrete, monuments to a bygone era of explosive growth and utopian dreams. Born from the ashes of war, these structures were the future, once. Now, they stand as weathered, beautiful beasts, their raw, unadorned concrete skins telling a story of ambition, community, and the passage of time. For urban explorers, photographers, and anyone looking to scope out a side of Japan that’s off the beaten path, these danchi are a whole mood. They represent a design philosophy called Brutalism, and when you see them through a modern lens, they radiate a powerful, gritty, cyberpunk aesthetic that’s absolutely captivating. It’s an exploration of a future that never quite happened, a concrete dreamscape waiting to be discovered. So, grab your comfiest shoes and your camera, because we’re about to dive deep into the concrete heart of Japan.

To further explore this unique architectural aesthetic, consider reading about Japan’s Bubble Era architecture.

The Concrete Canvas: Understanding the Showa Soul

Before we teleport into these concrete jungles, you need to get the backstory—it’s the key to unlocking the whole vibe. Let’s rewind to the Showa Era (1926–1989), specifically the period after World War II. Japan was undergoing a total transformation. Cities had been flattened, and a massive housing shortage emerged as people flocked to urban centers for work. The nation was rebuilding—and doing so fast. It was a time of incredible optimism, a can-do energy focused on progress, technology, and forging a new, modern Japan.

This is where the Japan Housing Corporation (JHC), now known as UR Urban Renaissance Agency, enters the scene in 1955. Their mission was ambitious: to build vast quantities of affordable, high-quality housing for the country’s growing workforce of salarymen and their families. The result was the danchi, a term meaning “group land.” These were not just buildings; they were entire planned communities set in the suburbs of major cities like Tokyo and Osaka. For the generation moving in, a danchi apartment was the ultimate dream. It symbolized success and modernity. Imagine moving from a cramped, traditional wooden house with shared facilities to a self-contained concrete apartment featuring a private kitchen, flush toilet, and stainless steel sink. It was revolutionary. These features were called the ‘3K’—kitchen, kitchen sink, and kettle—though the meaning later evolved to represent various aspirational home goods. This was the height of modern living: a clean, efficient, and private space to build a family and a future.

The architectural style that emerged grew out of necessity. Rapid and economical construction was essential, leading to standardization, prefabricated components, and above all, extensive use of reinforced concrete. This wasn’t about decorative flourishes; it was about pure, unfiltered function. Long, monolithic slab blocks arranged in neat rows, grids of repeating windows and balconies, and an unapologetic display of raw, exposed concrete. While rooted in practicality, this approach gave rise to an unintended aesthetic movement. It became Japan’s own take on Brutalism—a style that was at once monumental and human-scale, designed to house the masses and drive the nation forward. These danchi became the backdrop for the Japanese economic miracle, the concrete cradles where a new middle class was born.

Brutalism x Cyberpunk: A Match Made in a Dystopian Heaven

So, what exactly is Brutalism? The name sounds harsh, but it’s not about brutality. It originates from the French phrase béton brut, meaning “raw concrete.” This architectural movement reached its peak between the 1950s and 1970s, celebrating the authenticity of materials. Architects who embraced this style believed in exposing a building’s structural framework rather than concealing it with plaster and paint. They admired the rugged texture of wood-formed concrete, the bold, blocky forms, and the material’s sculptural strength. It was a rejection of delicacy and ornamentation in favor of something solid, strong, and honest.

So, how does this mid-20th-century architectural style connect with cyberpunk, a sci-fi subgenre that emerged in the 1980s? The link is found in the visual language. Cyberpunk revolves around the motto “high tech, low life,” depicting technologically advanced futures that are gritty, worn down, and socially divided. Think of the colossal, rain-soaked megastructures of Blade Runner’s Los Angeles, the dense, sprawling chaos of Neo-Tokyo in Akira, or the industrial decay in Ghost in the Shell. These worlds feature massive, imposing architecture—weathered buildings stained by pollution and time, covered with pipes and ducts, yet possessing a haunting, monumental beauty.

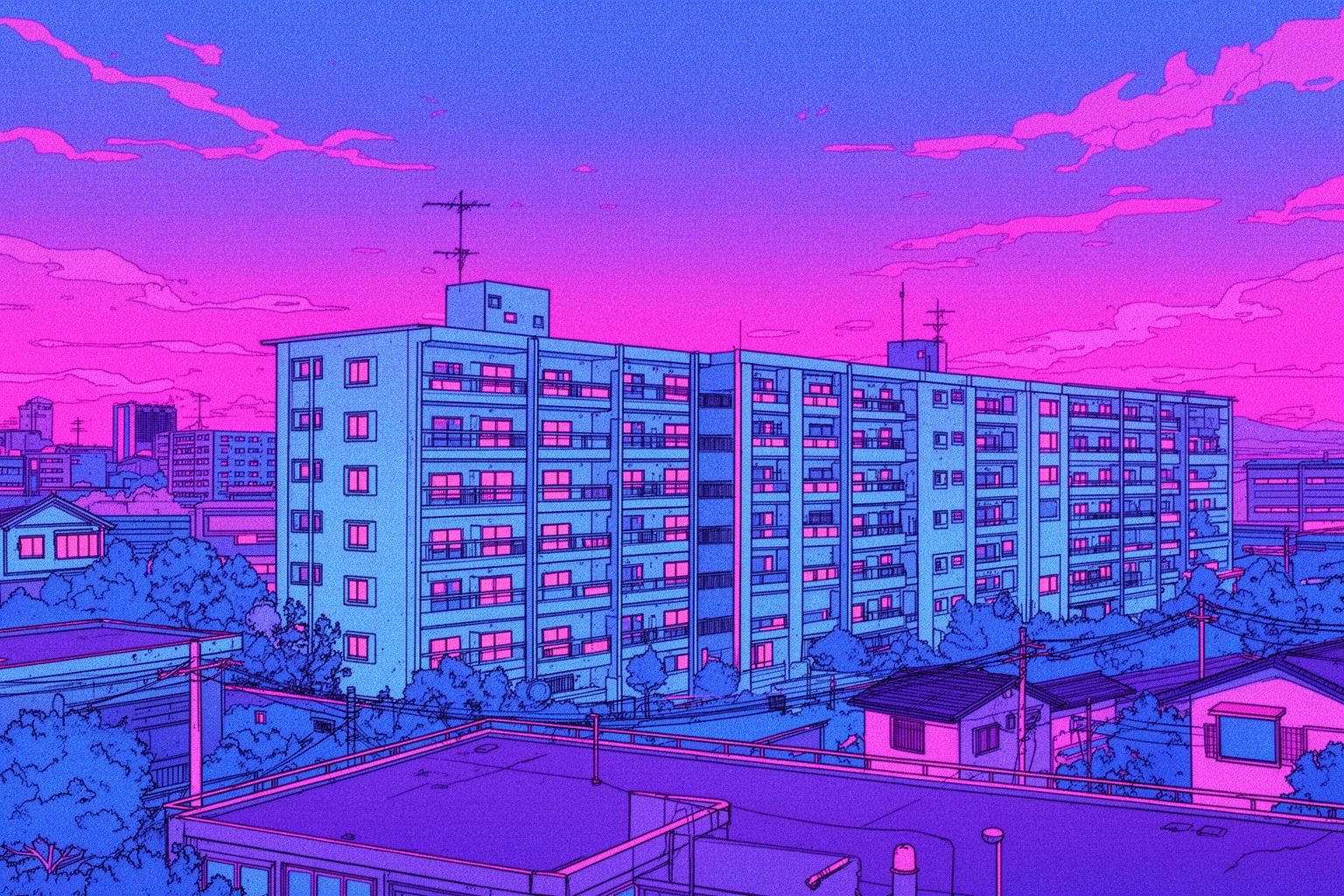

This is where Showa-era danchi fit seamlessly. Years of weather exposure have given their raw concrete facades a deep patina of age. Rain streaks run down their surfaces like tears, moss and ivy cling in crevices, and repairs and alterations add layers of history. The clean, utopian vision of the 1960s has evolved into something far more complex and visually captivating. The massive scale and repetitive geometry of these complexes, especially the larger ones, recall the megastructures of cyberpunk fiction. Elevated walkways connecting buildings become sky-bridges in a vertical city, and endless grids of windows resemble data streams in a digital realm made physical. When walking through a vast danchi on a grey, overcast day, or at dusk as lights flicker to life in thousands of identical windows, the atmosphere is pure cyberpunk. It’s a powerful aesthetic experience, a sensation of stepping into a tangible future-past. You’re not merely seeing old apartment blocks; you’re entering a living, breathing sci-fi set.

The Urban Explorer’s Hit List: Iconic Danchi You Have to See

Alright, theory class is finished. It’s time for the field trip. Japan is sprinkled with these concrete gems, but some stand out as more legendary than others. Visiting them involves a short train ride away from the city center, but the journey itself is part of the experience, transporting you from the sleek present to the gritty, textured past. Here are several must-see spots for your cyberpunk brutalist pilgrimage. A quick tip before we begin: remember these are people’s homes. The golden rule is to be a ghost. Stay quiet, be respectful, and focus your camera on the architecture, not the residents. Stick to public paths, parks, and common areas. Cool? Cool.

Akabanedai Danchi (NUG), Kita Ward, Tokyo: The Star of the Show

If you’re starting anywhere, start here. Akabanedai Danchi in northern Tokyo hosts one of the most famed and photogenic designs in danchi history: the “Star House.” While much of the original complex has been rebuilt and modernized, a few iconic buildings have been preserved by the UR agency as a tribute to their heritage. Thank goodness for that, because they’re stunning.

The Vibe Check: Stepping off at Akabane Station and walking uphill toward the NUG (New Urban Life Generation) section of the danchi feels like a treasure hunt. You pass modern apartment blocks, and then suddenly, there it is. The Star House, or sutā hausu, is a point-block building shaped like a ‘Y’. It’s completely unlike the long, rectangular slab blocks you might expect. The design was brilliant, ensuring every apartment received excellent sunlight and ventilation. The effect is sculptural, almost playful. It feels less like a block and more like a concrete star dropped from the sky. The surrounding area is quiet, residential, and filled with nostalgia. You can almost hear the echoes of children playing and families chatting from a bygone time.

Architectural Lowdown: The Y-shape is the main attraction. It creates intriguing angles and shadows that change throughout the day. Notice the external staircases spiraling up the structure, adding a dynamic, geometric touch. The concrete shows a perfect aged texture, and the repeating balcony patterns are hypnotic. The ground floor of one building has been turned into a small, free museum showcasing what a 1960s danchi apartment looked like. It’s a must-visit. Peeking inside at the vintage furniture and appliances truly brings the history to life.

Getting There & Practicalities: It’s very easy to reach. Take the JR Saikyo, Shonan-Shinjuku, or Keihin-Tohoku lines to Akabane Station. From there, it’s about a 10-15 minute uphill walk. The preserved Star Houses are in the Akabanedai NUG Stage 4 area. A quick map search for “Akabanedai Danchi Star House” will guide you right there. Daylight is ideal for photographing the building’s distinctive shape.

Photographer’s Playbook: Get low and shoot upwards to highlight the star shape against the sky. Play with shadows cast by the building’s three wings. The external staircases offer excellent opportunities for abstract geometric shots. Frame the building with nearby trees to create a sense of a discovered relic. The contrast between old concrete and green foliage is stunning.

Takashimadaira Danchi, Itabashi Ward, Tokyo: The Concrete Behemoth

While the Star House is about unique design, Takashimadaira Danchi is about sheer, overwhelming scale. This isn’t just a housing complex; it’s a city within a city. Built in the early 1970s, it’s one of Tokyo’s largest danchi, stretching for kilometers along the Toei Mita subway line. This is where you go to feel small, completely immersed in a world of concrete.

The Vibe Check: The atmosphere at Takashimadaira is awe, mixed with a hint of intimidation. As you exit Takashimadaira Station, you’re confronted by massive, 14-story concrete blocks that seem endless. The relentless repetition is mesmerizing. Elevated pedestrian walkways crisscross the complex, letting you traverse above roads and between buildings, reinforcing a sky-bridge, futuristic city feel. The complex is so vast it has its own ecosystem of shops, schools, parks, and clinics. It feels inhabited, but the scale lends it an impersonal, almost dystopian air. It’s the kind of place where you might imagine a cyberpunk detective chasing a replicant.

Architectural Lowdown: Scale is the star here. We’re talking a series of massive, long slab blocks forming concrete canyons. The design is brutally functional. Notice details within the repetition: balcony railing patterns, rhythmic stairwell window placement, the texture of weathered concrete panels. Elevated walkways are key; they serve as practical urban planning elements and powerful visuals. Walking them offers a fresh perspective, making you feel like you’re navigating a multi-level megastructure.

Getting There & Practicalities: Take the Toei Mita Line to Takashimadaira, Nishi-Takashimadaira, or Shin-Takashimadaira stations. The danchi encircles these stations, so it’s impossible to miss. You can spend hours walking from one end to the other. Because the complex is so extensive, there are plenty of public spaces, so you can explore without feeling intrusive. Cloudy days enhance the moody, brutalist vibe here.

Photographer’s Playbook: Use a wide-angle lens to capture the immense scale, though fitting it all in one frame is unlikely. Focus on leading lines—the long roads, walkways, building edges—that draw viewers into the scene. Seek moments of human activity for contrast: a person walking on a sky-bridge, laundry hanging from a balcony. These small details reveal life inside this concrete giant. The stations, especially elevated platforms, offer excellent vantage points for capturing the danchi extending into the distance.

Tokiwadaira Danchi, Matsudo, Chiba: The OG New Town

For a trip back to the origins of danchi, head just outside Tokyo to Tokiwadaira in Chiba Prefecture. Opened in 1960, this was among the first and largest “New Town” projects by the JHC. It was a prototype for the thousands of danchi that followed—a grand experiment in modern community planning.

The Vibe Check: Tokiwadaira feels different. It’s older, and you can sense that. The buildings are generally lower-rise—four or five stories—and the complex is incredibly green. The planners planted thousands of trees when it was built, and now, over sixty years later, they’ve grown into a lush urban forest. The vibe is less imposing cyberpunk and more nostalgic and serene. It feels like a time capsule. Walking the quiet lanes, you’ll encounter old-fashioned barbershops, small grocery stores, and playgrounds that have hosted generations of children. It’s a gentle, lived-in place, but the underlying brutalist DNA remains evident in the simple, honest concrete structures.

Architectural Lowdown: Tokiwadaira’s charm lies in its layout and integration with nature. Buildings are arranged to create communal green spaces and courtyards. Early danchi planning aimed to separate people from traffic while integrating nature into daily life. The buildings are simpler than later designs but have classic mid-century modern appeal. Look for simple geometric patterns, clean lines, and the way mature trees frame and soften the concrete facades. The complex is also famous for its cherry blossom tunnel—a lengthy road lined with sakura trees that create a spectacular sight in spring.

Getting There & Practicalities: Take the Shin-Keisei Line to Tokiwadaira Station. The danchi is right outside. This makes a great trip to combine with a park visit. The area is flat and easy to walk. Spring is obviously an ideal time because of the cherry blossoms, but the lush summer greenery and stark winter trees each offer their own unique, beautiful atmosphere.

Photographer’s Playbook: Focus on the interplay between human-made structures and nature. Capture concrete buildings peeking through thick tree canopies. Frame stark, geometric windows with delicate cherry blossoms. Look for details that speak to the place’s age: faded shop signs, retro playground gear, weathered concrete textures. It’s a setting for subtle, atmospheric photography that tells stories of time and memory.

Senri New Town, Osaka: The Western Front

Let’s leave the Kanto region and head west to Osaka, to one of the era’s most ambitious projects: Senri New Town. This wasn’t just another danchi; it was a vast, comprehensively planned city built from scratch to house hundreds of thousands of people for the 1970 World Expo. It’s a sprawling area showcasing diverse architectural styles from the 60s and 70s.

The Vibe Check: Exploring Senri New Town feels like visiting an open-air museum of Showa-era urban planning. It’s so large you need to use the local monorail or buses to get around. Each neighborhood has its own character and architectural experiments. Some areas are very uniform and grid-like; others feature unique, even futuristic designs. Planned on a grand scale, it includes huge parks, wide boulevards, and a spaciousness uncommon in danchi closer to city centers. The atmosphere shifts from utopian and orderly to eerily quiet depending on location. It’s a fascinating, complex place.

Architectural Lowdown: This is a paradise for architecture enthusiasts. You’ll find everything from standard slab blocks to experimental forms. Explore Senri-Chuo, the central hub, and surrounding residential zones like Shin-Senri-Higashimachi or Minami-Senri. Buildings feature bold colors, interesting structural designs, and impressive pedestrian systems. The sheer variety makes Senri compelling. It served as a laboratory for architects and planners, and their experiments continue to age gracefully.

Getting There & Practicalities: The main access point is Senri-Chuo Station on the Midosuji subway line (Kita-Osaka Kyuko Line) and the Osaka Monorail. From there, you can walk or take local buses to explore different neighborhoods. This is a full-day excursion. Plan your route or simply pick an area and wander. It’s a great way to experience a different side of Kansai, far from the crowds in Kyoto and central Osaka.

Photographer’s Playbook: Treat the visit like a safari hunting for unique architectural specimens. Elevated monorail tracks provide excellent vantage points for capturing the town’s scale. Look for symmetry and patterns in housing blocks, but also moments of irregularity that break the mold. The contrast between carefully planned infrastructure and nature’s gradual reclamation offers striking photo opportunities.

The Human Element: Life Inside the Concrete

It’s easy to get caught up in the aesthetics—the cool, detached beauty of the concrete and the sci-fi fantasies. But it’s crucial to remember that these danchi aren’t ruins or movie sets; they are vibrant, living communities. Once the dream for young families, the demographics have shifted over time. Many original residents are now elderly, having spent their entire adult lives within these concrete walls. This has created challenges, but it has also fostered a remarkable sense of community.

Stroll through any danchi on a weekday afternoon, and you’ll notice it: seniors chatting on benches in shared green spaces, children walking home from the on-site elementary school, the smell of dinner drifting from countless open windows. Behind the imposing structures, countless individual stories unfold. Each balcony is personalized with laundry, plants, or satellite dishes—small touches of individuality inside the uniform facade.

In recent years, there has been a significant effort to rejuvenate these aging complexes. The UR agency has led the way, renovating apartments with modern interiors to attract a new generation of residents. One of the most exciting projects is the MUJI x UR collaboration, which redesigns old danchi units using MUJI’s signature minimalist, beautiful, and functional style. It’s a brilliant pairing that injects fresh, contemporary energy into these Showa-era shells. This movement is introducing danchi living to young people, families, and creatives who value solid construction, spacious green areas, and more affordable rent compared to newer city apartments. It’s breathing new life into the concrete, ensuring these places remain homes—not just historical relics. It demonstrates that good design is timeless and that these concrete dreams are far from over.

Your Danchi Mission Brief: An Explorer’s Toolkit

Feeling excited and ready to embark on your own concrete pilgrimage? Fantastic. A bit of preparation will make your journey smooth and highly rewarding. Here’s a straightforward guide for your first deep dive into Danchi.

Gear Up: First things first: footwear. You’ll be doing a lot of walking. Seriously. Comfort is paramount. Forget the heels—grab your most reliable sneakers. Next, your camera. Whether it’s a professional DSLR or just your phone, make sure it’s fully charged. A portable power bank will be your best friend. A wide-angle lens is perfect for capturing scale, but a standard or telephoto lens can help isolate interesting architectural details from afar. Also, bring water and maybe a few snacks. While many large danchi feature convenience stores or vending machines, some smaller, older ones might not.

The Golden Rules of Etiquette: This is the most crucial part. I’ll repeat it because it’s important: YOU ARE A GUEST IN SOMEONE’S HOME. These are residential areas. Be like a ninja. Move quietly. Don’t shout or play loud music. Absolutely avoid entering any buildings, climbing on structures, or peeking into windows. That’s not only rude—it’s creepy and could cause trouble. When photographing, focus on the architecture. Avoid including residents in your shots, especially close-ups of faces or private balconies. If someone seems uneasy about your presence, simply give a polite nod and move on. The aim is to observe and appreciate, not to disturb.

Timing is Everything: The time of day you visit can completely change the atmosphere. Midday on a bright sunny day produces high-contrast light, generating deep, dramatic shadows that highlight the geometric shapes of the buildings—perfect for that iconic, bold Brutalist aesthetic. On the other hand, visiting on an overcast or rainy day can be enchanting. The grey sky complements the concrete, and wet surfaces create beautiful reflections. The mood becomes more melancholic and, dare I say, cyberpunk. The “golden hour” just before sunset is also stunning, bathing the concrete in a warm, soft glow you might not expect.

Navigation and Planning: Your smartphone will be your guide. Before you go, mark the locations you want to visit on Google Maps. Use satellite view to get a feel for the complex’s layout. Look for public parks, playgrounds, or community centers within the danchi—these are excellent starting points and guaranteed public spaces where you can relax without feeling intrusive. Don’t just stick to the main roads; explore the smaller pedestrian paths between buildings. That’s where you’ll discover hidden corners and the most captivating views.

More Than Just Concrete

So, there you have it—a journey into a side of Japan that’s often overlooked, yet filled with history, beauty, and a peculiar, futuristic nostalgia. These Showa-era danchi are far more than mere apartment blocks. They represent the tangible embodiment of a nation’s post-war aspirations. They are raw concrete canvases weathered by decades of sun, wind, and rain. They serve as living museums of architecture and urban planning. And for those who cherish the gritty, textured realms of cyberpunk, they become a real-life playground—a place where we can step into the futures we’ve only imagined in books or seen in films. Exploring them reminds us that beauty isn’t always found in the polished or traditionally picturesque. Sometimes, it lies in the vast, the weathered, and the beautifully, brutally honest. It lives in the concrete dreams of a generation, still standing proud against the sky.