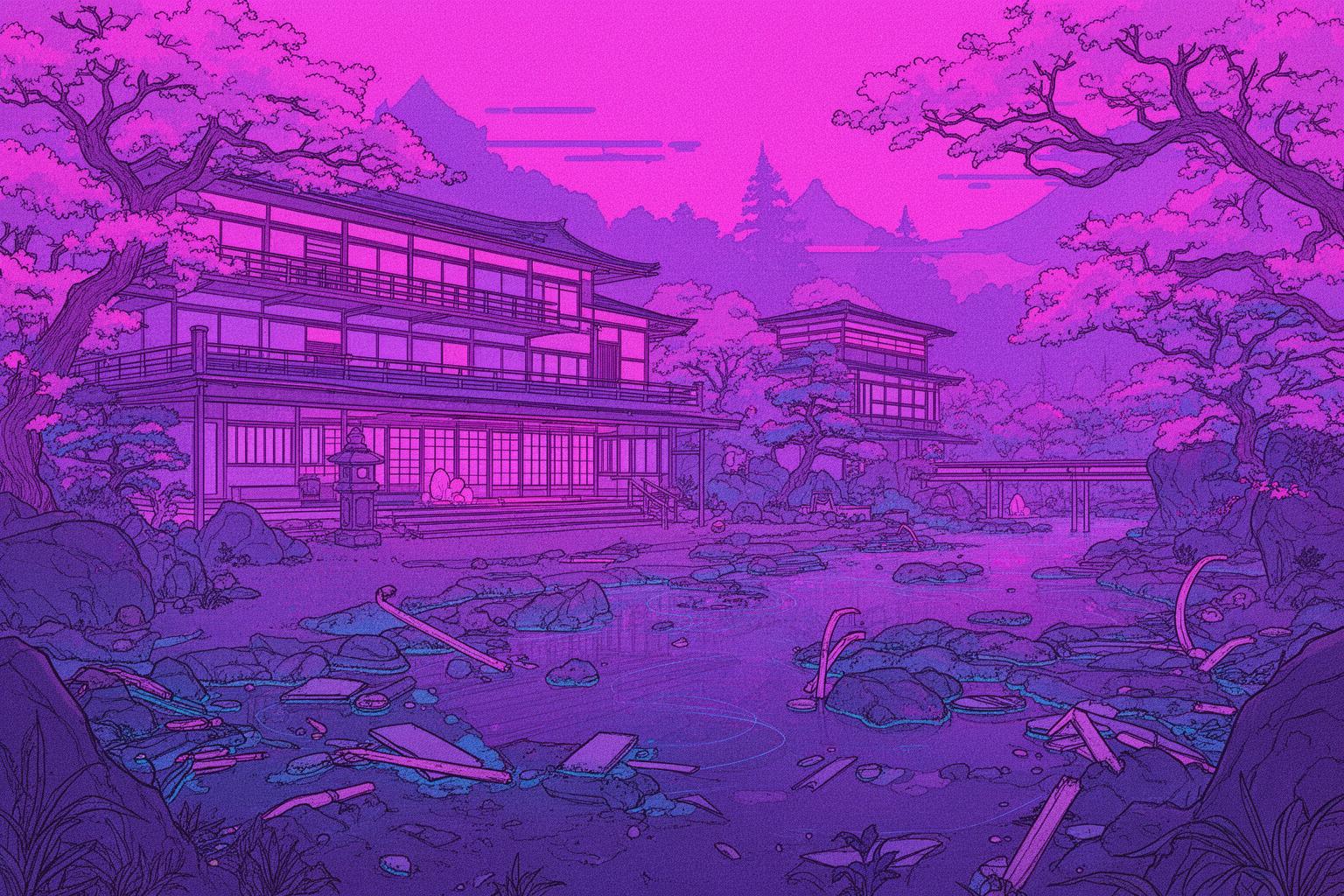

There’s a certain kind of quiet that settles over places that have been left behind. It’s not an empty quiet, but one thick with the whispers of what used to be. In Japan, a country that so perfectly balances the hyper-modern with the deeply traditional, this quiet has a unique texture, a particular resonance. You feel it most profoundly in the mountains, tucked away in valleys where steam rises from the earth itself. I’m talking about Japan’s onsen towns, those villages built around the lifeblood of natural hot springs. For generations, they were the heart of Japanese leisure, getaways for families, companies, and honeymooners. But time, as it does, moved on. And in its wake, it left behind towering spectres of a bygone era: the derelict onsen hotels, the grand ryokans now silent and surrendering to nature. These are not just ruins; they are time capsules, monuments to a forgotten boom, and they possess a strange, melancholic beauty that is utterly captivating. For the traveller who has seen the neon glow of Tokyo and the serene temples of Kyoto, these places offer a different kind of pilgrimage—one into the soul of modern Japan’s memory, a journey into a ghostly, yet profoundly peaceful, serenity.

This isn’t your typical tourist trail. It’s a path for the curious, the photographers, the historians, and those who find beauty in the imperfect. It’s about understanding a concept the Japanese call mono no aware—a gentle sadness for the transience of things. These husks of hospitality, with their faded velvet chairs and grand, empty ballrooms, are the physical embodiment of that feeling. They stand as silent witnesses to the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble in the early 1990s, a time of extravagant dreams and boundless optimism that came to a sudden, screeching halt. Visiting the towns where these giants sleep is to walk through a living museum of that dramatic shift in fortune. It’s about respectfully observing from the outside, understanding the story, and feeling the powerful atmosphere that hangs in the air, thick as the sulphuric steam from a nearby spring. It’s a side of Japan that asks for quiet contemplation rather than excited chatter, a travel experience that lingers long after you’ve gone home.

For a different perspective on Japan’s abandoned leisure destinations, consider exploring the eerie beauty of its forgotten amusement parks.

The Age of Opulence and its Quiet Aftermath

To truly grasp the silent grandeur of a derelict onsen hotel, you need to understand the world that created it. Picture Japan in the 1970s and 80s. The post-war economic miracle was in full swing, reaching its peak during the Bubble Economy. Money seemed endless. Cash-rich companies rewarded their employees with extravagant group trips, with onsen towns as the preferred destination. These were not quaint little inns; they were sprawling concrete giants, architectural wonders of their era, built to entertain hundreds, even thousands, of guests simultaneously. They were self-contained worlds of pleasure. Imagine massive banquet halls where sake flowed freely, glittering nightclubs with mirrored walls, elaborate game arcades blinking in the basement, and vast, steaming bathhouses offering panoramic views of surrounding mountains and rivers. They were monuments to prosperity, constructed with the confidence that the party would never end.

These hotels symbolized a distinct form of Japanese social life. The shain ryoko (company trip) was an institution, a crucial ritual for fostering camaraderie and reinforcing corporate loyalty. Entire departments would descend on an onsen town, spending their days in meetings or sightseeing and their nights clad in yukata, bonding over multi-course kaiseki dinners and karaoke. Families, too, saved for their annual onsen getaway, a chance to escape cramped city apartments and soak in healing waters. The hotels catered to everyone, providing entertainment for all ages. The atmosphere in these towns would have been electric, filled with laughter, the clatter of geta on pavement, and the melodies of enka music drifting from crowded bars.

Then, the bubble burst. The stock market crashed, property values collapsed, and the era of excess ended. Companies cut budgets, and extravagant group trips became relics of the past. Travel preferences shifted. Younger generations favored international travel or more personalized domestic trips over the traditional group experience. The giant, one-size-fits-all hotels began to struggle. They were costly to maintain, their design felt outdated, and their vast size became a burden. One by one, they closed their doors. Some were demolished, but many were simply abandoned—too expensive to tear down, with owners bankrupt or having walked away. Left to the elements, their grand lobbies and once-pristine tatami rooms became homes for dust, weeds, and the slow, relentless passage of time. This is the story etched into the peeling paint and broken windows of every derelict onsen hotel you might find looming over a tranquil river valley.

The Haikyo Hunters and the Wabi-Sabi Aesthetic

The allure of these sites has sparked a subculture in Japan and beyond known as haikyo, the exploration of ruins. However, it’s important to differentiate this from the adrenaline-charged trespassing common in Western urban exploration. While there is an adventurous aspect, haikyo in Japan tends to be a more contemplative, photographic endeavor. It is deeply rooted in traditional Japanese aesthetics, especially wabi-sabi—a worldview embracing transience and imperfection, finding beauty in what is “imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete.” A crumbling concrete wall with moss creeping through its cracks, a row of dusty glasses left on a bar, a lone child’s shoe in an empty corridor—these are not images of decay as ugliness but as poignant, profound beauty. It’s the beauty of decline, the quiet dignity of an object or place gracefully yielding to entropy.

Photographers are drawn to these spots like moths to a flickering flame. The quality of light within an abandoned hotel is unlike any other. Sunbeams pierce dust-laden air, highlighting forgotten details and crafting scenes of breathtaking melancholy. The aim is to capture the essence, the spirit of the place. It’s not about shock value but about composition, texture, and emotion. Each photo becomes an act of preservation, recording a moment in the building’s gradual return to nature. Remarkable images abound online—grand pianos thick with dust, bowling alleys where pins still stand, kitchens filled with pots and pans awaiting chefs who won’t come back. These photos invoke a universal fascination with the ‘post-apocalyptic’: a glimpse into a world without us. Yet they also resonate personally, hinting at the countless individual stories of joy, rest, and life that once animated these spaces.

Nevertheless, a vital word of caution must be emphasized—it is the most critical practical advice I can offer. Trespassing in Japan is illegal and taken very seriously. These structures are often perilously unstable, with dangers including collapsing floors, broken glass, and hazardous materials like asbestos. The haikyo community follows a strict code of ethics: take only pictures, leave only footprints. Still, even this can be a risk not worth taking. For the curious traveler, the beauty of these places can and should be appreciated from a safe and legal distance. The true experience lies not in breaking and entering, but in being present in the town itself, seeing these silent giants as part of the landscape, and understanding the history they embody. Their ghostly presence is often most powerful when viewed from a bridge spanning the river or from a hiking trail on the opposite mountain, where their scale and solitude can be fully grasped.

Kinugawa Onsen: A Tale of Two Realities

If you want to experience this atmosphere firsthand, few places are as powerful as Kinugawa Onsen in Tochigi Prefecture, located not far from the renowned shrines of Nikko. This town serves as a living diorama capturing the rise and fall of the onsen boom. Tucked within a dramatic river gorge, Kinugawa was once one of the Kanto region’s most popular resorts. Along the banks of the Kinugawa River, hotels line the shore, creating a striking contrast. On one side are lively, functioning ryokans, their lights glowing at night with steam drifting from open-air baths. On the opposite side stand their silent, darkened counterparts—immense buildings with shattered windows and faded facades, their bare concrete frames exposed to the sky. Walking along the river path is a surreal experience; you can hear the cheerful voices of tourists from the active hotels, while across the water, a ghostly past gazes back at you.

Exploring Kinugawa isn’t just about seeking ruins but about embracing this duality. You can take a boat ride down the river, a popular tourist activity that offers the most breathtaking and poignant views of the abandoned hotels. They loom over you, their emptiness sharply contrasting with the lively chatter on the boat. It’s a powerful, somewhat unsettling, and deeply memorable experience. Afterwards, immerse yourself in the living side of town. Visit a public onsen for a day soak, such as the excellent Kinugawa Koen Iwaburo, an outdoor bath right beside the river. Cross the Fureai Bridge, where you can admire the gorge and see both old and new hotels standing side by side. The town has made efforts to reinvent itself with attractions like Tobu World Square and the Edo Wonderland theme park nearby, catering to a new generation of visitors.

This is the key to responsibly enjoying a place like this. The past is always present but should not overshadow the present. Locals who continue to live and work in Kinugawa are striving to build a future—so support them. Eat at a neighborhood ramen shop. Buy souvenirs. Stay a night in one of the operating hotels and enjoy their impeccable hospitality. By engaging with the living town, you gain a deeper understanding of the ruins’ context. You witness the resilience of a community that has endured great economic upheaval. The ghostly hotels are not the whole story; they are just the most dramatic chapter in a long, ongoing narrative.

Practical Tips for a Reflective Journey

Reaching a town like Kinugawa Onsen is simple. From Tokyo, the Tobu Railway runs direct and limited express trains from Asakusa Station, making it an ideal day trip or a delightful overnight stay, especially when combined with a visit to Nikko. The most atmospheric time to visit might be late autumn or winter. Bare trees create a stark, skeletal landscape that complements the abandoned buildings. A light dusting of snow can transform the scene into something dreamlike, muffling sound and enhancing the profound silence. Spring, with its cherry blossoms, offers a poignant contrast—the vibrant, fleeting life of the sakura against the slow, steady decay of the structures.

While there, walk. Skip the bus and explore the side streets. This is where the town’s true texture reveals itself. You might come across a small, forgotten shrine, a retro-style coffee shop, or an old-fashioned sweets store. These little discoveries help make the experience uniquely yours. Keep in mind that these towns are often hilly, built along gorges and mountainsides, so comfortable shoes are essential. A good map, whether paper or digital, is useful, but don’t be afraid to wander—the size of these towns is usually quite manageable on foot.

A small tip for first-timers: embrace the onsen culture wholeheartedly. Don’t be shy. The rules are simple—wash thoroughly before entering the bath, don’t bring your towel into the water, and just relax. Soaking in a hot spring while gazing at the mountains—and perhaps spotting one of the silent hotels in the distance—is an experience that connects you directly to the history and spirit of the place. It bridges the vibrant present and the melancholic past.

Beyond Kinugawa: Other Echoes Across Japan

Though Kinugawa is a striking example, similar stories unfold in onsen towns throughout Japan. The Izu Peninsula, a classic retreat from Tokyo, also has its share of forgotten resorts, especially around the once-glamorous city of Atami. While Atami has experienced a revival in recent years, remnants of the bubble era still haunt its hillsides overlooking the sea. Further away, in the mountains of Gunma or the tranquil valleys of the Tohoku region, comparable tales exist. Each town possesses its own distinct character and history, yet the underlying story remains the same.

The key to discovering these places is not by searching lists of “top abandoned spots,” which may lead to unsafe or illegal encounters. Instead, investigate historic onsen towns that flourished in the mid to late 20th century. Compare old photographs to their modern state. When visiting, be attentive. The derelict hotels are not hidden; they are often the largest buildings in town, impossible to overlook. They blend into the landscape as much as the river or the forest. Let your exploration encompass the entire town. Take local hiking trails. Many onsen towns offer beautiful paths leading to viewpoints where you can often enjoy the most breathtaking and respectful panoramas of the valley, including its dormant giants.

This mindset transforms what could be a morbid curiosity into a meaningful cultural and historical journey. It’s about being a thoughtful observer rather than a thrill-seeker. It means viewing these buildings not as playgrounds for adventurers, but as memorials. They stand as tributes to the people who constructed them, the employees who worked there, and the millions of guests who once filled their halls with laughter. They serve as tangible reminders of economic forces that can reshape a nation and the resilience of communities tasked with rebuilding and redefining themselves.

The Art of Observation and Respectful Photography

For those drawn to these sites with a camera, creative possibilities abound, even from public vantage points. The aim is to narrate the story of the place through your lens. Instead of hunting for dramatic interior shots, focus on how these structures interact with their surroundings. A telephoto lens can be invaluable, allowing you to isolate details from a safe distance—a broken window catching the sunset, vines reclaiming a balcony, the faded name of a hotel in peeling kanji. Frame the abandoned hotel against the living town or stunning natural backdrop. Contrast the rigid, decaying lines of the building with the soft, organic shapes of the mountains or flowing river.

Consider the time of day. The gentle light of dawn or dusk adds a magical, ethereal quality to the scene. Overcast skies are ideal too, as diffused light highlights texture and detail without harsh shadows. A misty morning can produce an eerie atmosphere, with hotel rooftops disappearing into low-hanging clouds. The goal is to capture the mood, the mono no aware. Your photograph should evoke gentle melancholy, wonder, and the quiet passage of time. This contemplative style of photography demands patience and a profound empathy for the location.

Keep the human element in mind, even when people are absent. Though you won’t capture individuals inside, your images can still evoke the human experience. A shot of a darkened ballroom window can suggest the thousands of dances once held there. A wide, empty car park can hint at the daily convoys of tour buses that arrived. By focusing on these traces of vanished lives, your photography becomes a powerful narrative, honoring the memory of the place rather than merely documenting its decay.

A Different Kind of Healing

People visit onsen towns seeking healing. The mineral-rich waters are believed to ease ailments, relax the body, and soothe the mind. In a sense, a trip to one of these towns, with its silent, dormant giants, offers another form of healing—a healing of perspective. In today’s fast-paced world, we are conditioned to prize the new, the shiny, and the successful. We are taught to discard what is old or broken. Yet these places challenge that mindset. They reveal the beauty and dignity found in imperfection, age, and even failure. They remind us that nothing lasts forever, and there is a certain peace in accepting that truth.

Standing on a bridge in a quiet onsen town, gazing at a grand hotel slowly being overtaken by the forest, you feel connected to the cycles of nature and time. The ambition behind the hotel’s creation, the joy it once hosted, and its eventual decline are all chapters of the same story. It is a humbling and deeply moving experience that encourages a slower, more mindful way of traveling—one that focuses less on checking off sights and more on absorbing the atmosphere and reflecting on the stories the place holds.

So, if you’re a traveler seeking a deeper connection, a side of Japan beyond the glossy posters, consider a journey to an onsen town partly forgotten by time. Visit to soak in the healing waters, yes, but also to witness the silent poetry of what has been left behind. Don’t come to break down doors, but to have your perspectives gently opened. You will find a ghostly serenity there, an echo in the steam that lingers—a quiet and beautiful reminder of life’s transient, imperfect, and utterly fascinating nature.